List of Roman birth and childhood deities

In ancient Roman religion, birth and childhood deities were thought to care for every aspect of conception, pregnancy, childbirth, and child development. Some major deities of Roman religion had a specialized function they contributed to this sphere of human life, while other deities are known only by the name with which they were invoked to promote or avert a particular action. Several of these slight "divinities of the moment"[1] are mentioned in surviving texts only by Christian polemicists.[2]

An extensive Greek and Latin medical literature covered obstetrics and infant care, and the 2nd century Greek gynecologist Soranus of Ephesus advised midwives not to be superstitious. But childbirth in antiquity remained a life-threatening experience for both the woman and her newborn, with infant mortality as high as 30 or 40 percent.[3] Rites of passage pertaining to birth and death had several parallel aspects.[4] Maternal death was common: one of the most famous was Julia, daughter of Julius Caesar and wife of Pompey. Her infant died a few days later, severing the family ties between her father and husband and hastening the Caesar's Civil War, which ended the Roman Republic.[5] Some ritual practices may be characterized as anxious superstitions, but the religious aura surrounding childbirth reflects the high value Romans placed on family, tradition (mos maiorum), and compatibility of the sexes.[6] Under the Empire, children were celebrated on coins, as was Juno Lucina, the primary goddess of childbirth, as well as in public art.[7] Funerary art, such as relief on sarcophagi, sometimes showed scenes from the deceased's life, including birth or the first bath.[8]

Only those who died after the age of 10 were given full funeral and commemorative rites, which in ancient Rome were observed by families several days during the year (see Parentalia). Infants less than one year of age received no formal rites. The lack of ritual observances pertains to the legal status of the individual in society, not the emotional response of families to the loss.[9] As Cicero reflected:

Some think that if a small child dies this must be borne with equanimity; if it is still in its cradle there should not even be a lament. And yet it is from the latter that nature has more cruelly demanded back the gift she had given.[10]

Sources

The most extensive lists of deities pertaining to the conception-birth-development cycle come from the Church Fathers, especially Augustine of Hippo and Tertullian. Augustine in particular is known to have used the now-fragmentary theological works of Marcus Terentius Varro, the 1st century BC Roman scholar, who in turn referenced the books of the Roman pontiffs. The purpose of the patristic writers was to debunk traditional Roman religion, but they provide useful information despite their mocking tone.[11] Scattered mentions occur throughout Latin literature.

The following list of deities is organized chronologically by the role they play in the process.[12]

Conception and pregnancy

The gods of the marriage bed (di coniugales) are also gods of conception.[13] Juno, one of the three deities of the Capitoline Triad, presides over union and marriage as well, and some of the minor deities invoked for success in conceiving and delivering a child may have been functional aspects of her powers.

- Jugatinus is a conjugal god, from iugare, "to join, yoke, marry."[14]

- Cinxia functions within the belt (cingulum) that the bride wears to symbolize that her husband is "belted and bound" (cinctus vinctusque) to her.[15] It was tied with the knot of Hercules, intended to be intricate and difficult to untie.[16] Augustine calls this goddess Virginiensis (virgo, "virgin"), indicating that the untying is the symbolic loss of virginity.[17] Cinxia may have been felt as present during a ritual meant to ease labor. The man who fathered the child removes his own belt (cinctus), binds it (cinxerit) around the laboring woman, then releases it with a prayer that the one who has bound her in labor should likewise release her: "he should then leave."[18] Women who had experienced spontaneous abortions were advised to bind their bellies for the full nine months with a belt (cingulum) of wool from a lamb fed upon by a wolf.[19]

- Subigus is the god (deus) who causes the bride to give in to her husband.[20] The name derives from the verb subigo, subigere, "to cause to go under; tame, subdue," used of the active role in sexual intercourse, hence "cause to submit sexually".[21]

- Prema is the insistent sex act, from the verb primo, primere, to press upon. Although the verb usually describes the masculine role, Augustine calls Prema dea Mater, a mother goddess.[22]

- Inuus ("Entry"), the phallic god Mutunus Tutunus, and Pertunda enable sexual penetration. Inuus, sometimes identified with Faunus, embodies the mammalian impulse toward mating. The cult of Mutunus was associated with the sacred fascinum.[23] Both these gods are attested outside conception litany. Pertunda is the female personification[24] of the verb pertundere, "to penetrate",[25] and seems to be a name for invoking a divine power specific to this function.

- Janus, the forward- and backward-facing god of doorways and passages, "opened up access to the generative seed which was provided by Saturn," the god of sowing.[26]

- Consevius or Deus Consevius, also Consivius, is the god of propagation and insemination,[27] from con-serere, "to sow." It is a title of Janus as a creator god or god of beginnings.[28]

- Liber Pater ("Father Liber") empowers the man to release his semen,[29] while Libera does the same for the woman, who was regarded as also contributing semina, "seed."[30]

- Mena or Dea Mena with Juno assured menstrual flow,[31] which is redirected to feed the developing child.[32]

- Fluonia or Fluvionia, from fluo, fluere, "to flow," is a form of Juno who retains the nourishing blood within the womb.[33] Women attended to the cult of Juno Fluonia "because she held back the flow of blood (i.e., menstruation) in the act of conception."[34] Medieval mythographers noted this aspect of Juno,[35] which marked a woman as a mater rather than a virgo.[36]

- Alemona feeds the embryo[37] or generally nourished growth in utero.[38]

- Vitumnus endows the fetus with vita, "life" or the vital principle or power of life (see also quickening).[39] Augustine calls him the vivificator, "creator of life," and links him with Sentinus (following) as two "very obscure" gods who are examples of the misplaced priorities of the Roman pantheon. These two gods, he suggests, should merit inclusion among the di selecti, "select" or principal gods, instead of those who preside over physical functions such as Janus, Saturn, Liber and Libera.[40] Both Vitumnus and Sentinus were most likely names that focalized the functions of Jove.[41]

- Sentinus or Sentia gives sentience or the powers of sense perception (sensus).[42] Augustine calls him the sensificator, "creator of sentience."[43]

The Parcae

The Parcae are the three goddesses of fate (tria fata): Nona, Decima, and Parca (singular of Parcae), also known as Partula in relation to birthing. Nona and Decima determine the right time for birth, assuring the completion of the nine-month term (ten in Roman inclusive counting).[44] Parca or Partula oversees partus, birth as the initial separation from the mother's body (as in English '"postpartum").[45] At the very moment of birth, or immediately after, Parca establishes that the new life will have a limit, and therefore she is also a goddess of death called Morta (English "mortal").[46] The profatio Parcae, "prophecy of Parca," marked the child as a mortal being, and was not a pronouncement of individual destiny.[47] The first week of the child's life was regarded as an extremely perilous and tentative time, and the child was not recognized as an individual until the dies lustricus.

Birthing

The primary deity presiding over the delivery was Juno Lucina, who may in fact be a form of Diana. Those invoking her aid let their hair down and loosened their clothing as a form of reverse binding ritual intended to facilitate labor.[48] Soranus advised women about to give birth to unbind their hair and loosen clothing to promote relaxation, not for any magical effect.[49]

- Egeria, the nymph, received sacrifices from pregnant women in order to bring out (egerere) the baby.[50]

- Postverta and Prosa avert breech birth.[51]

- Diespiter (Jupiter) brings the baby toward the daylight.[52]

- Lucina introduces the baby to the light (lux, lucis).[53]

- Vagitanus or Vaticanus opens the newborn's mouth for its first cry.[54]

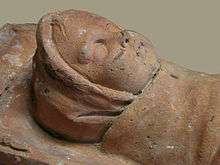

- Levana lifts the baby, who was ceremonially placed on the ground after birth in symbolic contact with Mother Earth. (In antiquity, kneeling or squatting was a more common birthing position than it is in modern times; see di nixi.[55]) The midwife then cut the umbilical cord and presented the newborn to the mother, a scene sometimes depicted on sarcophagi. A grandmother or maternal aunt next cradled the infant in her arms; with a finger covered in lustral saliva, she massaged the baby's forehead and lips, a gesture meant to ward off the evil eye.[56]

- Statina (also Statilina, Statinus or Statilinus) gives the baby fitness or "straightness,"[57] and the father held it up to acknowledge his responsibility to raise it. Unwanted children might be abandoned at the Temple of Pietas or the Columna Lactaria. Newborns with serious birth defects might be drowned or smothered.[58]

Into the light

Lucina as a title of the birth goddess is usually seen as a metaphor for bringing the newborn into the light (lux, lucis).[59] Luces, plural ("lights"), can mean "periods of light, daylight hours, days." Diespiter, "Father of Day," is thus her masculine counterpart; if his name is taken as a doublet for Jupiter, then Juno Lucina and Diespiter can be understood as a male-female complement.[60]

Diespiter, however, is also identified in Latin literature with the ruler of the underworld, Dis pater. The functions of "chthonic" deities such as Dis (or Pluto) and his consort Proserpina are not confined to death; they are often concerned with agricultural fertility and the giving of nourishment for life, since plants for food grow from seeds hidden in the ground. In the mystery religions, the divine couple preside over the soul's "birth" or rebirth in the afterlife. The shadowy goddess Mana Genita was likewise concerned with both birth and mortality, particularly of infants, as was Hecate.[61]

In contrast to the vast majority of deities, both birth goddesses and underworld deities received sacrifices at night.[62] Ancient writers conventionally situate labor and birth at night; it may be that night is thought of as the darkness of the womb, from which the newborn emerges into the (day)light.

The cyclical place of the goddess Candelifera, "She who bears the candle,"[63] is uncertain. It is sometimes thought that she provides an artificial light for labor that occurs at night. A long labor was considered likely for first-time mothers, so at least a part of the birthing process would occur at night.[64] According to Plutarch,[65] light symbolizes birth, but the candle may have been thought of as less a symbol than an actual kindling of life,[66] or a magic equivalent to the life of the infant.[67] Candelifera may also be the nursery light kept burning against spirits of darkness that would threaten the infant in the coming week.[68] Even in the Christian era, lamps were lit in nurseries to illuminate sacred images and drive away child-snatching demons such as the Gello.[69]

Neonatal care

Once the child came into the light, a number of rituals were enacted over the course of the following week.[70] An offerings table received congratulatory sacrifices from the mother's female friends.[71] Three deities—Intercidona, Pilumnus, and Deverra—were invoked to drive away Silvanus, the wild woodland god of trees:[72] three men secured the household every night by striking the threshold (limen; see liminality) with an axe and then a pestle, followed by sweeping it.

In the atrium of the house, a bed was made up for Juno, and a table set for Hercules.[73] In the Hellenized mythological tradition, Juno tried to prevent the birth of Hercules, as it resulted from Jupiter's infidelity. Ovid has Lucina crossing her knees and fingers to bind the labor.[74] Etruscan religion, however, emphasized the role that Juno (as Uni) played in endowing Hercle with his divine nature through the drinking of her breast milk.

- Intercidona provides the axe without which trees cannot be cut (intercidere).

- Pilumnus or Picumnus grants the pestle necessary for making flour from grain.

- Deverra gives the broom with which grain was swept up (verrere) (compare Averruncus).

- Juno in her bed represents the nursing mother.[75]

- Hercules represents the child who requires feeding.

- Rumina promotes suckling.[76] This goddess received libations of milk, an uncommon liquid offering among the Romans.[77]

- Nundina presides over the dies lustricus.[78]

- At some point in time the two Carmentes[79] (Antevorta and Postverta), had something to do with childrens fates as well.[80]

Child development

In well-to-do households, children were cared for by nursemaids (nutrices, singular nutrix, which can mean either a wet nurse who might be a slave or a paid professional of free status, or more generally any nursery maid, who would be a household slave). Mothers with a nursery staff were still expected to supervise the quality of care, education, and emotional wellbeing of children. Ideally, fathers would take an interest even in their infant children; Cato liked to be present when his wife bathed and swaddled their child.[81] Nursemaids might make their own bloodless offerings to deities who protected and fostered the growth of children.[82] Most of the "teaching gods" are female, perhaps because they themselves were thought of as divine nursemaids. The gods who encourage speech, however, are male.[83] The ability to speak well was a defining characteristic of the elite citizen. Although women were admired for speaking persuasively,[84] oratory was regarded as a masculine pursuit essential to public life.[85]

- Potina (Potica or Potua) from the noun potio "drink" (Bibesia in some source editions, cf verb bibo, bibere "drink") enables the child to drink.[86]

- Edusa, from the verb edo, edere, esus, "eat," also as Edulia, Edula, Educa, Edesia etc., enables the taking of nourishment.[87] The variations of her name may indicate that while her functional focus was narrow, her name had not stabilized; she was mainly a divine force to be invoked ad hoc for a specific purpose.[88]

- Ossipago builds strong bones;[89] probably a title of Juno, from ossa, "bones," + pango, pangere, "insert, fix, set." Alternative readings of the text include Ossipagina, Ossilago, Opigena, Ossipanga, Ossipango, and Ossipaga.[90]

- Carna makes strong muscles, and defends the internal organs from witches or strigae.

- Cunina protects the cradle from malevolent magic.[91]

- Cuba helps the child transition from cradle to a bed.

- Paventia or Paventina averts fear (pavor) from the child.[92]

- Peta sees to its "first wants."[93]

- Agenoria endows the child with a capacity to lead an active life.[94]

- Adeona and Abeona monitor the child's comings and goings[95]

- Interduca and Domiduca accompany it leaving the house and coming home again.[96]

- Catius pater, "Father Catius," is invoked for sharpening the minds of children as they develop intellectually.[97]

- Farinus enables speech.

- Fabulinus prompts the child's first words.

- Locutius enables it to form sentences.

- Mens ("Mind") provides it with intelligence.

- Volumnus or Volumna grants the child the will to do good.[98]

- Numeria gives the child the ability to count.

- Camena enables it to sing.[99]

- The Muses give the ability to appreciate the arts, literature, and science.[100]

Children wore the toga praetexta, with a purple band that marked them as sacred and inviolable, and an amulet (bulla) to ward off malevolence.

Later literature

James Joyce mentions a few Roman birth deities by name in his works. In the "Oxen of the Sun" episode of Ulysses, he combines an allusion to Horace (nunc est bibendum) with an invocation of Partula and Pertunda (per deam Partulam et Pertundam) in anticipation of the birth of Purefoy. Cunina, Statulina, and Edulia are mentioned in Finnegans Wake.[101]

See also

- Di nixi, birth deities as a collective

- Indigitamenta, lists of invocational epithets that include many of the birth and child development deities

- Mana Genita, a goddess of infant mortality

- Mater Matuta

- Women in ancient Rome

References

- Giulia Sissa, "Maidenhood without Maidenhead: The Female Body in Ancient Greece," in Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World (Princeton University Press, 1990), p. 362, translating the German term Augenblicksgötter which was coined by Hermann Usener.

- Mary Beard, J.A. North, and S.R.F. Price, Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook (Cambridge University Press, 1998), vol. 2, p. 33.

- M. Golden, "Did the Ancients Care When Their Children Died?" Greece & Rome 35 (1988) 152–163; Keith R. Bradley, "Wet-nursing at Rome: A Study in Social Relations," in The Family in Ancient Rome: New Perspectives (Cornell University Press, 1986, 1992), p. 202; Beryl Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 104.

- Anthony Corbeill, "Blood, Milk, and Tears: The Gestures of Mourning Women," in Nature Embodied: Gesture in Ancient Rome (Princeton University Press, 2004), pp. 67–105.

- Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy, p. 103.

- Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy, p. 99.

- Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy, p. 64.

- Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy, pp. 101–102.

- Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy, p. 104.

- Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 1.93,as cited by Rawson, Children and Childhood in Roman Italy, p. 104.

- Beard et al., Religions of Rome,vol. 2, p. 33.

- The order is based on that of Robert Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome (Routledge, 2001; originally published in French 1998), pp. 18–20, and Jörg Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome: Rationalization and Ritual Change (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), pp. 181–182.

- Beard, Religions of Rome: A Sourcebook, vol. 2, pp. 32–33; Rüpke, Religion of the Romans, p. 79.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 6.9.Ludwig Preller, Römische Mythologie (Berlin, 1881), vol. 1, p. 211.

- Festus 55 (edition of Lindsay); Karen K. Hersch, The Roman Wedding: Ritual and Meaning in Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. 101, 110, 211.

- William Warde Fowler, The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic (London, 1908), p. 142.

- For an extensive look at the knot of virginity, primarily in early Christian culture, see S. Panayotakis, "The Knot and the Hymen: A Reconsideration of Nodus Virginitatis (Hist. Apoll. 1)," Mnemosyne 53.5 (2000) 599–608.

- Pliny, Natural History 28.42; Anthony Corbeill, Nature Embodied: Gesture in Ancient Rome (Princeton University Press, 2004), pp. 35–36.

- Attributed to Theodorus Priscianus, Additamenta 10; Corbeill, Nature Embodied, p. 37. See also Marcellus Empiricus, De medicamentis 10.70 and 82.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 6.9.

- J.N. Adams, The Latin Sexual Vocabulary (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982), pp. 155–156. The verb is used in the satiric verses chanted by the soldiers at the triumph of Julius Caesar, where he is said to have caused the Gauls to submit (see Gallic Wars), and to have submitted himself to Nicomedes. A subigitatrix was a woman who took the active role in fondling (Plautus, Persa 227).

- Adams, Latin Sexual Vocabulary, p. 182; Augustine, De Civitate Dei 6.9.

- The cult of this god was either misunderstood or deliberately misrepresented by Church Fathers as a ritual deflowering during marriage rites; no Roman source describes such a thing. See Mutunus Tutunus.

- Sissa, "Maidenhood without Maidenhead," p. 362.

- Augustine of Hippo, De Civitate Dei 6.9.3.

- Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 18.

- Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Fowler, Roman Festivals, p. 289. Macrobius, Saturnalia `1.9, lists Consivius among the titles of Janus from the act of sowing (a conserendo), that is, "the propagation of the human race," with Janus as the auctor ("increaser," source, author). Macrobius says that the title Consivia also belongs to the goddess Ops.

- Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 18, citing Augustine, De Civitate Dei 6.9.3.

- Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 18, citing Augustine, De Civitate Dei IV.11: dea Mena, quam praefecerunt menstruis feminarum :"The goddess Mena, who was put in charge of menstruation" This may seem illogically placed in the sequence; Roman girls were not married until they were ready for childbearing, so menstruation would mark the bride as old enough to marry, and conception would halt the flow.

- Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Tertullian, Ad nationes 2.11.3; Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 18.

- Excerpts from Paulus in Festus, p. 82 (edition of Lindsay): mulieres colebant, quod eam sanguinis fluorem in conceptu retinere putabant.

- Juno "is called Fluonia, from the flowing (fluoribus) of seed, because she frees women in childbirth," according to the Third Vatican Mythographer, as translated by Ronald E. Pepin, The Vatican Mythographers (Fordham University Press, 2008), p. 225. Fluoribus might also be translated as "emissions, discharge." The Berlin Commentary to the De nuptiis of Martianus Capella (2.92) compares this moisture to the dew that drips from the air and nourishes seeds; Haijo Jan Westra and Tanja Kupke, The Berlin Commentary on Martianus Capella's De Nuptiis Philologie et Mercurii, Book II (Brill, 1998), p. 93.

- In his commentary on the De nuptiis of Martianus Capella, Remigius of Auxerre "explains Fluvonia from the contraceptive use of the discharges of seeds to free women from childbirth"; see Jane Chance, Medieval Mythography from Roman North Africa to the School of Chartres, A.D. 433–1177 (University Press of Florida, 1994), p.286.

- Tertullian, De anima 37.1 (Alemonam alendi in utero fetus); Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 18.

- Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 7.2–3; see also Tertullian, Ad nationes 2.11.

- Preller, Römische Mythologie, p. 208.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 7.3.1; Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Augustine's point is that a monotheistic concept of deity obviates the need for dispersing these functions and for a divine taxonomy that is based on knowledge rather than faith. One view of the success of Christianity is that it was simple to understand and required a less complex theology; see Preller, Römische Mythologie, p. 208, and Michael Lipka, Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach (Brill, 2009), pp. 84–88.

- Tertullian, De anima 37.1.

- Varro, as preserved by Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 3.16.9–10; Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- S. Breemer and J. H. Waszink, "Fata Scribunda," in Opuscula Selecta (Brill, 1979), p. 247.

- Breemer and Waszink, "Fata Scribunda," p. 248.

- Corbeill, Nature Embodied, p. 36.

- Corbeill, Nature Embodied, p. 36.

- Festus p. 67 (edition of Lindsay): Egeriae nymphae sacrificabant praegnantes, quod eam putabant facile conceptum alvo egere; Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 18.

- Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 18.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.11; Tertullian, Ad nationes 2.11; Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Ovid, Fasti 2.451f.; Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Aulus Gellius 16.1.2.

- Pierre Grimal, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology (Blackwell, 1986, 1996, originally published 1951 in French), pp. 311–312; Charles J. Adamec, "Genu, genus," Classical Philology 15 (1920), p. 199; J.G. Frazer, Pausanias's Description of Greece (London, 1913), vol. 4, p. 436; Marcel Le Glay, "Remarques sur la notion de Salus dans la religion romaine," La soteriologia dei culti orientali nell' imperio romano: Études préliminaires au religions orientales dans l'empire romain, Colloquio internazionale Roma, 1979 (Brill, 1982), p. 442.

- Persius 2.31–34; Robert Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome (Routledge, 2001; originally published in French 1998), p. 20.

- Tertullian, De anima 39.2; Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.21.

- Seneca, De ira 1.15.2.

- Ovid provides an alternate derivation as the "goddess of the grove" (lucus), but in ancient etymology the word lucus itself was thought to derive from luc-, "light": the lucus as a "sacred grove" was actually the creation of a clearing (i.e., the letting in of light) within a grove to make a sacred place. The sacred grove of Lucina was located on the Esquiline Hill.

- Celia E. Schultz, Women's Religious Activity in the Roman Republic (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 79–81; Michael Lipka, Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach (Brill, 2009), pp. 141–142

- H.J. Rose, The Roman Questions of Plutarch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924, 1974), p. 192; David and Noelle Soren, A Roman Villa and a Late Roman Infant Cemetery («L'Erma» di Bretschneider, 1999), p. 520.

- Lipka, Roman Gods, p. 154, especially note 22. The animal sacrifices offered to most deities are domestic herd animals normally raised for food; the deity honored is given a portion, and the rest of the roasted flesh is shared by humans in a communal meal. Both birth goddesses and chthonic deities, however, typically receive an inedible victim, often puppies or bitches, in the form of a holocaust or burnt offering, with no shared meal.

- Tertullian, Ad nationes 2.11:

- The passage in Tertullian has a problematic point that may specify first births; Gaston Boissier, Étude sur la vie et les ouvrages de M.T. Varron (Hachette, 1861), pp. 234–235.

- Plutarch, Roman Questions 2.

- H.J. Rose, The Roman Questions of Plutarch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924, 1974), p. 170.

- Eli Edward Burriss, Taboo, Magic, Spirits: A Study of Primitive Elements in Roman Religion (1931; Forgotten Books reprint, 2007), p. 34.

- Rose, The Roman Questions of Plutarch, pp. 79, 170.

- According to Leo Allatios, De Graecorum hodie quorundam opinationibus IV (1645), p. 188 as cited by Karen Hartnup, On the Beliefs of the Greeks: Leo Allatios and Popular Orthodoxy (Brill, 2004), p. 95.

- Rüpke, Religion in Republican Rome, p. 181.

- Nonius, p. 312, 11–13, as cited by Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 19.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 6.9.2.

- Servius Danielis, note to Eclogue 4.62 and Aeneid 10.76.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 9.298–299; Corbeill, Nature Embodied, pp. 37, 93.

- Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 19.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.11, 21, 34; 7.11.

- Plutarch, Life of Romulus 4.1.

- Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.16.36.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.11.

- Tertullian, De anima 39.2.

- Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder 20.2.

- Varro, Logistorici frg. 9 (Bolisani), as cited by Lora L. Holland, "Women and Roman Religion," in A Companion to Women in the Ancient World (Blackwell, 2012), p. 212.

- Preller, Römische Mythologie, p. 211.

- For example, according to Roman tradition the speech made by Lucretia in response to her rape sparked the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of the Roman Republic.

- Joseph Farrell, Latin Language and Latin Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2001), pp. 74–75; Richard A. Bauman, Women and Politics in Ancient Rome (Routledge, 1992, 1994), pp. 51–52.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.11, 34.

- Augustine, De civitate Dei 4.11.

- Michael Lipka, Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach (Brill, 2009), pp. 126–127.

- Arnobius, Adversus Nationes 4.7–8: Ossipago quae durat et solidat infantibus parvis ossa. Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 20.

- George Englert McCracken, commentary on Arnobius's The Case Against the Pagans (Paulist Press, 1949), p. 364; W.H. Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie (Leipzig: Teubner, 1890–94), vol. 2, pt. 1, p. 209.

- Lactantius, Divine Institutes 1.20.36.

- Tertullian, Ad nationes 2.11; Augustine of Hippo, De civitate Dei 4.11; Gerardus Vossius, De physiologia Christiana et theologia gentili 8.6: Paventia ab infantibus avertebat pavorem, 7.5; Lipka, Roman Gods, p. 128.

- Arnobius 4.7.

- Augustine of Hippo, De Civitate Dei 4.11; Christian Laes, Children in the Roman Empire: Outsiders Within (Cambridge University Press, 2011, originally published 2006 in Dutch), p. 68.

- Jordan, Michael (1993). Encyclopedia of gods : over 2,500 deities of the world. Internet Archive. New York : Facts on File. pp. 1.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.21; Tertullian, Ad nationes 2.11.9.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.21: Father Catius, "who makes [children] clever, that is, sharp-witted" (qui catos id est acutos faceret).

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.21.

- Augustine, De Civitate Dei 4.11.

- Turcan, The Gods of Ancient Rome, p. 21.

- R.J. Schork, Latin and Roman Culture in Joyce (University Press of Florida, 1997), p. 105.