PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL (/ˈpoʊstɡrɛs ˌkjuː ˈɛl/),[13] also known as Postgres, is a free and open-source relational database management system (RDBMS) emphasizing extensibility and SQL compliance. It was originally named POSTGRES, referring to its origins as a successor to the Ingres database developed at the University of California, Berkeley.[14][15] In 1996, the project was renamed to PostgreSQL to reflect its support for SQL. After a review in 2007, the development team decided to keep the name PostgreSQL and the alias Postgres.[16]

The World's Most Advanced Open Source Relational Database[2] | |

| Developer(s) | PostgreSQL Global Development Group[3] |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 8 July 1996[4] |

| Stable release | 12.4

/ 13 August 2020[5] |

| Preview release | 13 Beta 3

/ 13 August 2020[5] |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | FreeBSD, Linux, macOS, OpenBSD, Windows[6] |

| Type | RDBMS |

| License | PostgreSQL License (free and open-source, permissive)[7][8][9] |

| Website | postgresql |

| Publisher | PostgreSQL Global Development Group Regents of the University of California |

|---|---|

| DFSG compatible | Yes[10][11] |

| FSF approved | Yes[12] |

| OSI approved | Yes[9] |

| GPL compatible | Yes |

| Copyleft | No |

| Linking from code with a different licence | Yes |

| Website | postgresql |

PostgreSQL features transactions with Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability (ACID) properties, automatically updatable views, materialized views, triggers, foreign keys, and stored procedures.[17] It is designed to handle a range of workloads, from single machines to data warehouses or Web services with many concurrent users. It is the default database for macOS Server,[18][19][20] and is also available for Linux, FreeBSD, OpenBSD, and Windows.

History

PostgreSQL evolved from the Ingres project at the University of California, Berkeley. In 1982, the leader of the Ingres team, Michael Stonebraker, left Berkeley to make a proprietary version of Ingres.[14] He returned to Berkeley in 1985, and began a post-Ingres project to address the problems with contemporary database systems that had become increasingly clear during the early 1980s. He won the Turing Award in 2014 for these and other projects,[21] and techniques pioneered in them.

The new project, POSTGRES, aimed to add the fewest features needed to completely support data types.[22] These features included the ability to define types and to fully describe relationships – something used widely, but maintained entirely by the user. In POSTGRES, the database understood relationships, and could retrieve information in related tables in a natural way using rules. POSTGRES used many of the ideas of Ingres, but not its code.[23]

Starting in 1986, published papers described the basis of the system, and a prototype version was shown at the 1988 ACM SIGMOD Conference. The team released version 1 to a small number of users in June 1989, followed by version 2 with a re-written rules system in June 1990. Version 3, released in 1991, again re-wrote the rules system, and added support for multiple storage managers[24] and an improved query engine. By 1993, the number of users began to overwhelm the project with requests for support and features. After releasing version 4.2[25] on June 30, 1994 – primarily a cleanup – the project ended. Berkeley released POSTGRES under an MIT License variant, which enabled other developers to use the code for any use. At the time, POSTGRES used an Ingres-influenced POSTQUEL query language interpreter, which could be interactively used with a console application named monitor.

In 1994, Berkeley graduate students Andrew Yu and Jolly Chen replaced the POSTQUEL query language interpreter with one for the SQL query language, creating Postgres95. monitor was also replaced by psql. Yu and Chen announced the first version (0.01) to beta testers on May 5, 1995. Version 1.0 of Postgres95 was announced on September 5, 1995, with a more liberal license that enabled the software to be freely modifiable.

On July 8, 1996, Marc Fournier at Hub.org Networking Services provided the first non-university development server for the open-source development effort.[4] With the participation of Bruce Momjian and Vadim B. Mikheev, work began to stabilize the code inherited from Berkeley.

In 1996, the project was renamed to PostgreSQL to reflect its support for SQL. The online presence at the website PostgreSQL.org began on October 22, 1996.[26] The first PostgreSQL release formed version 6.0 on January 29, 1997. Since then developers and volunteers around the world have maintained the software as The PostgreSQL Global Development Group.[3]

The project continues to make releases available under its free and open-source software PostgreSQL License. Code comes from contributions from proprietary vendors, support companies, and open-source programmers.

Multiversion concurrency control (MVCC)

PostgreSQL manages concurrency through multiversion concurrency control (MVCC), which gives each transaction a "snapshot" of the database, allowing changes to be made without affecting other transactions. This largely eliminates the need for read locks, and ensures the database maintains ACID principles. PostgreSQL offers three levels of transaction isolation: Read Committed, Repeatable Read and Serializable. Because PostgreSQL is immune to dirty reads, requesting a Read Uncommitted transaction isolation level provides read committed instead. PostgreSQL supports full serializability via the serializable snapshot isolation (SSI) method.[27]

Storage and replication

Replication

PostgreSQL includes built-in binary replication based on shipping the changes (write-ahead logs (WAL)) to replica nodes asynchronously, with the ability to run read-only queries against these replicated nodes. This allows splitting read traffic among multiple nodes efficiently. Earlier replication software that allowed similar read scaling normally relied on adding replication triggers to the master, increasing load.

PostgreSQL includes built-in synchronous replication[28] that ensures that, for each write transaction, the master waits until at least one replica node has written the data to its transaction log. Unlike other database systems, the durability of a transaction (whether it is asynchronous or synchronous) can be specified per-database, per-user, per-session or even per-transaction. This can be useful for workloads that do not require such guarantees, and may not be wanted for all data as it slows down performance due to the requirement of the confirmation of the transaction reaching the synchronous standby.

Standby servers can be synchronous or asynchronous. Synchronous standby servers can be specified in the configuration which determines which servers are candidates for synchronous replication. The first in the list that is actively streaming will be used as the current synchronous server. When this fails, the system fails over to the next in line.

Synchronous multi-master replication is not included in the PostgreSQL core. Postgres-XC which is based on PostgreSQL provides scalable synchronous multi-master replication.[29] It is licensed under the same license as PostgreSQL. A related project is called Postgres-XL. Postgres-R is yet another fork.[30] Bidirectional replication (BDR) is an asynchronous multi-master replication system for PostgreSQL.[31]

Tools such as repmgr make managing replication clusters easier.

Several asynchronous trigger-based replication packages are available. These remain useful even after introduction of the expanded core abilities, for situations where binary replication of a full database cluster is inappropriate:

- Slony-I

- Londiste, part of SkyTools (developed by Skype)

- Bucardo multi-master replication (developed by Backcountry.com)[32]

- SymmetricDS multi-master, multi-tier replication

YugabyteDB is a database which uses the front-end of PostgreSQL with a more NoSQL-like backend. While it can be thought of as a different database, it is essentially PostgreSQL with a different storage backend. It addresses the replication issues with an implementation of the ideas from Google Spanner. Such databases are called NewSQL and include CockroachDB, and TiDB among others.

Indexes

PostgreSQL includes built-in support for regular B-tree and hash table indexes, and four index access methods: generalized search trees (GiST), generalized inverted indexes (GIN), Space-Partitioned GiST (SP-GiST)[33] and Block Range Indexes (BRIN). In addition, user-defined index methods can be created, although this is quite an involved process. Indexes in PostgreSQL also support the following features:

- Expression indexes can be created with an index of the result of an expression or function, instead of simply the value of a column.

- Partial indexes, which only index part of a table, can be created by adding a WHERE clause to the end of the CREATE INDEX statement. This allows a smaller index to be created.

- The planner is able to use multiple indexes together to satisfy complex queries, using temporary in-memory bitmap index operations (useful for data warehouse applications for joining a large fact table to smaller dimension tables such as those arranged in a star schema).

- k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) indexing (also referred to KNN-GiST[34]) provides efficient searching of "closest values" to that specified, useful to finding similar words, or close objects or locations with geospatial data. This is achieved without exhaustive matching of values.

- Index-only scans often allow the system to fetch data from indexes without ever having to access the main table.

- PostgreSQL 9.5 introduced Block Range Indexes (BRIN).

Schemas

In PostgreSQL, a schema holds all objects, except for roles and tablespaces. Schemas effectively act like namespaces, allowing objects of the same name to co-exist in the same database. By default, newly created databases have a schema called public, but any further schemas can be added, and the public schema isn't mandatory.

A search_path setting determines the order in which PostgreSQL checks schemas for unqualified objects (those without a prefixed schema). By default, it is set to $user, public ($user refers to the currently connected database user). This default can be set on a database or role level, but as it is a session parameter, it can be freely changed (even multiple times) during a client session, affecting that session only.

Non-existent schemas listed in search_path are silently skipped during objects lookup.

New objects are created in whichever valid schema (one that presently exists) appears first in the search_path.

Data types

A wide variety of native data types are supported, including:

- Boolean

- Arbitrary precision numerics

- Character (text, varchar, char)

- Binary

- Date/time (timestamp/time with/without time zone, date, interval)

- Money

- Enum

- Bit strings

- Text search type

- Composite

- HStore, an extension enabled key-value store within PostgreSQL[35]

- Arrays (variable length and can be of any data type, including text and composite types) up to 1 GB in total storage size

- Geometric primitives

- IPv4 and IPv6 addresses

- Classless Inter-Domain Routing (CIDR) blocks and MAC addresses

- XML supporting XPath queries

- Universally unique identifier (UUID)

- JavaScript Object Notation (JSON), and a faster binary JSONB (not the same as BSON[36])

In addition, users can create their own data types which can usually be made fully indexable via PostgreSQL's indexing infrastructures – GiST, GIN, SP-GiST. Examples of these include the geographic information system (GIS) data types from the PostGIS project for PostgreSQL.

There is also a data type called a domain, which is the same as any other data type but with optional constraints defined by the creator of that domain. This means any data entered into a column using the domain will have to conform to whichever constraints were defined as part of the domain.

A data type that represents a range of data can be used which are called range types. These can be discrete ranges (e.g. all integer values 1 to 10) or continuous ranges (e.g., any time between 10:00 am and 11:00 am). The built-in range types available include ranges of integers, big integers, decimal numbers, time stamps (with and without time zone) and dates.

Custom range types can be created to make new types of ranges available, such as IP address ranges using the inet type as a base, or float ranges using the float data type as a base. Range types support inclusive and exclusive range boundaries using the [/] and (/) characters respectively. (e.g., [4,9) represents all integers starting from and including 4 up to but not including 9.) Range types are also compatible with existing operators used to check for overlap, containment, right of etc.

User-defined objects

New types of almost all objects inside the database can be created, including:

- Casts

- Conversions

- Data types

- Data domains

- Functions, including aggregate functions and window functions

- Indexes including custom indexes for custom types

- Operators (existing ones can be overloaded)

- Procedural languages

Inheritance

Tables can be set to inherit their characteristics from a parent table. Data in child tables will appear to exist in the parent tables, unless data is selected from the parent table using the ONLY keyword, i.e. SELECT * FROM ONLY parent_table;. Adding a column in the parent table will cause that column to appear in the child table.

Inheritance can be used to implement table partitioning, using either triggers or rules to direct inserts to the parent table into the proper child tables.

As of 2010, this feature is not fully supported yet – in particular, table constraints are not currently inheritable. All check constraints and not-null constraints on a parent table are automatically inherited by its children. Other types of constraints (unique, primary key, and foreign key constraints) are not inherited.

Inheritance provides a way to map the features of generalization hierarchies depicted in entity relationship diagrams (ERDs) directly into the PostgreSQL database.

Other storage features

- Referential integrity constraints including foreign key constraints, column constraints, and row checks

- Binary and textual large-object storage

- Tablespaces

- Per-column collation

- Online backup

- Point-in-time recovery, implemented using write-ahead logging

- In-place upgrades with pg_upgrade for less downtime (supports upgrades from 8.3.x[37] and later)

Control and connectivity

Foreign data wrappers

PostgreSQL can link to other systems to retrieve data via foreign data wrappers (FDWs).[38] These can take the form of any data source, such as a file system, another relational database management system (RDBMS), or a web service. This means that regular database queries can use these data sources like regular tables, and even join multiple data-sources together.

Interfaces

For connecting to applications, PostgreSQL includes the built-in interfaces libpq (the official C application interface) and ECPG (an embedded C system). Third-party libraries for connecting to PostgreSQL are available for many programming languages, including C++,[39] Java,[40] Python,[41] Node.js,[42] Go,[43] and Rust.[44]

Procedural languages

Procedural languages allow developers to extend the database with custom subroutines (functions), often called stored procedures. These functions can be used to build database triggers (functions invoked on modification of certain data) and custom data types and aggregate functions.[45] Procedural languages can also be invoked without defining a function, using a DO command at SQL level.[46]

Languages are divided into two groups: Procedures written in safe languages are sandboxed and can be safely created and used by any user. Procedures written in unsafe languages can only be created by superusers, because they allow bypassing a database's security restrictions, but can also access sources external to the database. Some languages like Perl provide both safe and unsafe versions.

PostgreSQL has built-in support for three procedural languages:

- Plain SQL (safe). Simpler SQL functions can get expanded inline into the calling (SQL) query, which saves function call overhead and allows the query optimizer to "see inside" the function.

- Procedural Language/PostgreSQL (PL/pgSQL) (safe), which resembles Oracle's Procedural Language for SQL (PL/SQL) procedural language and SQL/Persistent Stored Modules (SQL/PSM).

- C (unsafe), which allows loading one or more custom shared library into the database. Functions written in C offer the best performance, but bugs in code can crash and potentially corrupt the database. Most built-in functions are written in C.

In addition, PostgreSQL allows procedural languages to be loaded into the database through extensions. Three language extensions are included with PostgreSQL to support Perl, Python (by default Python 2, or Python 3 possible)[47] and Tcl. There are external projects to add support for many other languages,[48] including Java, JavaScript (PL/V8), R, Ruby, and others.

Triggers

Triggers are events triggered by the action of SQL data manipulation language (DML) statements. For example, an INSERT statement might activate a trigger that checks if the values of the statement are valid. Most triggers are only activated by either INSERT or UPDATE statements.

Triggers are fully supported and can be attached to tables. Triggers can be per-column and conditional, in that UPDATE triggers can target specific columns of a table, and triggers can be told to execute under a set of conditions as specified in the trigger's WHERE clause. Triggers can be attached to views by using the INSTEAD OF condition. Multiple triggers are fired in alphabetical order. In addition to calling functions written in the native PL/pgSQL, triggers can also invoke functions written in other languages like PL/Python or PL/Perl.

Asynchronous notifications

PostgreSQL provides an asynchronous messaging system that is accessed through the NOTIFY, LISTEN and UNLISTEN commands. A session can issue a NOTIFY command, along with the user-specified channel and an optional payload, to mark a particular event occurring. Other sessions are able to detect these events by issuing a LISTEN command, which can listen to a particular channel. This functionality can be used for a wide variety of purposes, such as letting other sessions know when a table has updated or for separate applications to detect when a particular action has been performed. Such a system prevents the need for continuous polling by applications to see if anything has yet changed, and reducing unnecessary overhead. Notifications are fully transactional, in that messages are not sent until the transaction they were sent from is committed. This eliminates the problem of messages being sent for an action being performed which is then rolled back.

Many connectors for PostgreSQL provide support for this notification system (including libpq, JDBC, Npgsql, psycopg and node.js) so it can be used by external applications.

PostgreSQL can act as an effective, persistent "pub/sub" server or job server by combining LISTEN with FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED,[49] a combination which has existed since PostgreSQL version 9.5[50][51]

Rules

Rules allow the "query tree" of an incoming query to be rewritten. "Query Re-Write Rules" are attached to a table/class and "Re-Write" the incoming DML (select, insert, update, and/or delete) into one or more queries that either replace the original DML statement or execute in addition to it. Query Re-Write occurs after DML statement parsing, but before query planning.

Other querying features

- Transactions

- Full-text search

- Views

- Inner, outer (full, left and right), and cross joins

- Sub-selects

- Correlated sub-queries[55]

- Regular expressions[56]

- common table expressions and writable common table expressions

- Encrypted connections via Transport Layer Security (TLS); current versions do not use vulnerable SSL, even with that configuration option[57]

- Domains

- Savepoints

- Two-phase commit

- The Oversized-Attribute Storage Technique (TOAST) is used to transparently store large table attributes (such as big MIME attachments or XML messages) in a separate area, with automatic compression.

- Embedded SQL is implemented using preprocessor. SQL code is first written embedded into C code. Then code is run through ECPG preprocessor, which replaces SQL with calls to code library. Then code can be compiled using a C compiler. Embedding works also with C++ but it does not recognize all C++ constructs.

Concurrency model

PostgreSQL server is process-based (not threaded), and uses one operating system process per database session. Multiple sessions are automatically spread across all available CPUs by the operating system. Starting with PostgreSQL 9.6, many types of queries can also be parallelized across multiple background worker processes, taking advantage of multiple CPUs or cores.[58] Client applications can use threads and create multiple database connections from each thread.[59]

Security

PostgreSQL manages its internal security on a per-role basis. A role is generally regarded to be a user (a role that can log in), or a group (a role of which other roles are members). Permissions can be granted or revoked on any object down to the column level, and can also allow/prevent the creation of new objects at the database, schema or table levels.

PostgreSQL's SECURITY LABEL feature (extension to SQL standards), allows for additional security; with a bundled loadable module that supports label-based mandatory access control (MAC) based on Security-Enhanced Linux (SELinux) security policy.[60][61]

PostgreSQL natively supports a broad number of external authentication mechanisms, including:

- Password: either SCRAM-SHA-256 (since PostgreSQL 10[62]), MD5 or plain-text

- Generic Security Services Application Program Interface (GSSAPI)

- Security Support Provider Interface (SSPI)

- Kerberos

- ident (maps O/S user-name as provided by an ident server to database user-name)

- Peer (maps local user name to database user name)

- Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP)

- Active Directory (AD)

- RADIUS

- Certificate

- Pluggable authentication module (PAM)

The GSSAPI, SSPI, Kerberos, peer, ident and certificate methods can also use a specified "map" file that lists which users matched by that authentication system are allowed to connect as a specific database user.

These methods are specified in the cluster's host-based authentication configuration file (pg_hba.conf), which determines what connections are allowed. This allows control over which user can connect to which database, where they can connect from (IP address, IP address range, domain socket), which authentication system will be enforced, and whether the connection must use Transport Layer Security (TLS).

Standards compliance

PostgreSQL claims high, but not complete, conformance with the SQL standard. One exception is the handling of unquoted identifiers like table or column names. In PostgreSQL they are folded – internal – to lower case characters[63] whereas the standard says that unquoted identifiers should be folded to upper case. Thus, Foo should be equivalent to FOO not foo according to the standard.

Benchmarks and performance

Many informal performance studies of PostgreSQL have been done.[64] Performance improvements aimed at improving scalability began heavily with version 8.1. Simple benchmarks between version 8.0 and version 8.4 showed that the latter was more than 10 times faster on read-only workloads and at least 7.5 times faster on both read and write workloads.[65]

The first industry-standard and peer-validated benchmark was completed in June 2007, using the Sun Java System Application Server (proprietary version of GlassFish) 9.0 Platform Edition, UltraSPARC T1-based Sun Fire server and PostgreSQL 8.2.[66] This result of 778.14 SPECjAppServer2004 JOPS@Standard compares favourably with the 874 JOPS@Standard with Oracle 10 on an Itanium-based HP-UX system.[64]

In August 2007, Sun submitted an improved benchmark score of 813.73 SPECjAppServer2004 JOPS@Standard. With the system under test at a reduced price, the price/performance improved from $84.98/JOPS to $70.57/JOPS.[67]

The default configuration of PostgreSQL uses only a small amount of dedicated memory for performance-critical purposes such as caching database blocks and sorting. This limitation is primarily because older operating systems required kernel changes to allow allocating large blocks of shared memory.[68] PostgreSQL.org provides advice on basic recommended performance practice in a wiki.[69]

In April 2012, Robert Haas of EnterpriseDB demonstrated PostgreSQL 9.2's linear CPU scalability using a server with 64 cores.[70]

Matloob Khushi performed benchmarking between Postgresql 9.0 and MySQL 5.6.15 for their ability to process genomic data. In his performance analysis he found that PostgreSQL extracts overlapping genomic regions eight times faster than MySQL using two datasets of 80,000 each forming random human DNA regions. Insertion and data uploads in PostgreSQL were also better, although general searching ability of both databases was almost equivalent.[71]

Platforms

PostgreSQL is available for the following operating systems: Linux (all recent distributions), 64-bit installers available for macOS (OS X)[20] version 10.6 and newer – Windows (with installers available for 64-bit version; tested on latest versions and back to Windows 2012 R2,[72] while for PostgreSQL version 10 and older a 32-bit installer is available and tested down to 32-bit Windows 2008 R1; compilable by e.g. Visual Studio, version 2013 up up to most recent 2019 version) – FreeBSD, OpenBSD,[73] NetBSD, AIX, HP-UX, Solaris, and UnixWare; and not officially tested: DragonFly BSD, BSD/OS, IRIX, OpenIndiana,[74] OpenSolaris, OpenServer, and Tru64 UNIX. Most other Unix-like systems could also work; most modern do support.

PostgreSQL works on any of the following instruction set architectures: x86 and x86-64 on Windows and other operating systems; these are supported on other than Windows: IA-64 Itanium (external support for HP-UX), PowerPC, PowerPC 64, S/390, S/390x, SPARC, SPARC 64, ARMv8-A (64-bit)[75] and older ARM (32-bit, including older such as ARMv6 in Raspberry Pi[76]), MIPS, MIPSel, and PA-RISC. It was also known to work on some other platforms (while not been tested on for years, i.e. for latest versions).[77]

Database administration

Open source front-ends and tools for administering PostgreSQL include:

- psql

- The primary front-end for PostgreSQL is the

psqlcommand-line program, which can be used to enter SQL queries directly, or execute them from a file. In addition, psql provides a number of meta-commands and various shell-like features to facilitate writing scripts and automating a wide variety of tasks; for example tab completion of object names and SQL syntax. - pgAdmin

- The pgAdmin package is a free and open-source graphical user interface (GUI) administration tool for PostgreSQL, which is supported on many computer platforms.[78] The program is available in more than a dozen languages. The first prototype, named pgManager, was written for PostgreSQL 6.3.2 from 1998, and rewritten and released as pgAdmin under the GNU General Public License (GPL) in later months. The second incarnation (named pgAdmin II) was a complete rewrite, first released on January 16, 2002. The third version, pgAdmin III, was originally released under the Artistic License and then released under the same license as PostgreSQL. Unlike prior versions that were written in Visual Basic, pgAdmin III is written in C++, using the wxWidgets[79] framework allowing it to run on most common operating systems. The query tool includes a scripting language called pgScript for supporting admin and development tasks. In December 2014, Dave Page, the pgAdmin project founder and primary developer,[80] announced that with the shift towards web-based models, work has begun on pgAdmin 4 with the aim to facilitate cloud deployments.[81] In 2016, pgAdmin 4 was released. pgAdmin 4 backend was written in Python, using Flask and Qt framework.[82]

- phpPgAdmin

- phpPgAdmin is a web-based administration tool for PostgreSQL written in PHP and based on the popular phpMyAdmin interface originally written for MySQL administration.[83]

- PostgreSQL Studio

- PostgreSQL Studio allows users to perform essential PostgreSQL database development tasks from a web-based console. PostgreSQL Studio allows users to work with cloud databases without the need to open firewalls.[84]

- TeamPostgreSQL

- AJAX/JavaScript-driven web interface for PostgreSQL. Allows browsing, maintaining and creating data and database objects via a web browser. The interface offers tabbed SQL editor with autocompletion, row editing widgets, click-through foreign key navigation between rows and tables, favorites management for commonly used scripts, among other features. Supports SSH for both the web interface and the database connections. Installers are available for Windows, Macintosh, and Linux, and a simple cross-platform archive that runs from a script.[85]

- LibreOffice, OpenOffice.org

- LibreOffice and OpenOffice.org Base can be used as a front-end for PostgreSQL.[86][87]

- pgBadger

- The pgBadger PostgreSQL log analyzer generates detailed reports from a PostgreSQL log file.[88]

- pgDevOps

- pgDevOps is a suite of web tools to install & manage multiple PostgreSQL versions, extensions, and community components, develop SQL queries, monitor running databases and find performance problems.[89]

- Adminer

- Adminer is a simple web-based administration tool for PostgreSQL and others, written in PHP.

A number of companies offer proprietary tools for PostgreSQL. They often consist of a universal core that is adapted for various specific database products. These tools mostly share the administration features with the open source tools but offer improvements in data modeling, importing, exporting or reporting.

Notable users

Notable organizations and products that use PostgreSQL as the primary database include:

- In 2009, the social-networking website Myspace used Aster Data Systems's nCluster database for data warehousing, which was built on unmodified PostgreSQL.[90][91]

- Geni.com uses PostgreSQL for their main genealogy database.[92]

- OpenStreetMap, a collaborative project to create a free editable map of the world.[93]

- Afilias, domain registries for .org, .info and others.[94][95]

- Sony Online multiplayer online games.[96]

- BASF, shopping platform for their agribusiness portal.[97]

- Reddit social news website.[98]

- Skype VoIP application, central business databases.[99]

- Sun xVM, Sun's virtualization and datacenter automation suite.[100]

- MusicBrainz, open online music encyclopedia.[101]

- The International Space Station – to collect telemetry data in orbit and replicate it to the ground.[102]

- MyYearbook social-networking site.[103]

- Instagram, a mobile photo-sharing service.[104]

- Disqus, an online discussion and commenting service.[105]

- TripAdvisor, travel-information website of mostly user-generated content.[106]

- Yandex, a Russian internet company switched its Yandex.Mail service from Oracle to Postgres.[107]

- Amazon Redshift, part of AWS, a columnar online analytical processing (OLAP) system based on ParAccel's Postgres modifications.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) National Weather Service (NWS), Interactive Forecast Preparation System (IFPS), a system that integrates data from the NEXRAD weather radars, surface, and hydrology systems to build detailed localized forecast models.[95][108]

- United Kingdom's national weather service, Met Office, has begun swapping Oracle for PostgreSQL in a strategy to deploy more open source technology.[108][109]

- WhitePages.com had been using Oracle[110] and MySQL, but when it came to moving its core directories in-house, it turned to PostgreSQL. Because WhitePages.com needs to combine large sets of data from multiple sources, PostgreSQL's ability to load and index data at high rates was a key to its decision to use PostgreSQL.[95]

- FlightAware, a flight tracking website.[111]

- Grofers, an online grocery delivery service.[112]

- The Guardian migrated from MongoDB to PostgreSQL in 2018.[113]

Service implementations

Some notable vendors offer PostgreSQL as software as a service:

- Heroku, a platform as a service provider, has supported PostgreSQL since the start in 2007.[114] They offer value-add features like full database roll-back (ability to restore a database from any specified time),[115] which is based on WAL-E, open-source software developed by Heroku.[116]

- In January 2012, EnterpriseDB released a cloud version of both PostgreSQL and their own proprietary Postgres Plus Advanced Server with automated provisioning for failover, replication, load-balancing, and scaling. It runs on Amazon Web Services.[117] Since 2015, Postgres Advanced Server has been offered as ApsaraDB for PPAS, a relational database as a service on Alibaba Cloud.[118]

- VMware has offered vFabric Postgres (also termed vPostgres[119]) for private clouds on VMware vSphere since May 2012.[120] The company announced End of Availability (EOA) of the product in 2014.[121]

- In November 2013, Amazon Web Services announced the addition of PostgreSQL to their Relational Database Service offering.[122][123]

- In November 2016, Amazon Web Services announced the addition of PostgreSQL compatibility to their cloud-native Amazon Aurora managed database offering.[124]

- In May 2017, Microsoft Azure announced Azure Databases for PostgreSQL[125]

- In May 2019, Alibaba Cloud announced PolarDB for PostgreSQL.[126]

- Jelastic Multicloud Platform as a Service provides container-based PostgreSQL support since 2011. They offer automated asynchronous master-slave replication of PostgreSQL available from marketplace.[127]

- In June 2019, IBM Cloud announced IBM Cloud Hyper Protect DBaaS for PostgreSQL[128].

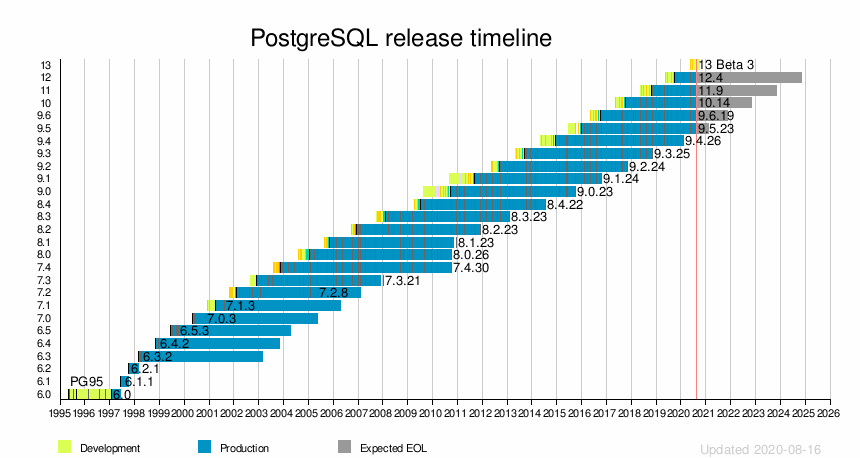

Release history

| Release | First release | Latest minor version | Latest release | End of life[129] |

Milestones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.0 | 1997-01-29 | N/A | N/A | N/A | First formal release of PostgreSQL, unique indexes, pg_dumpall utility, ident authentication |

| 6.1 | 1997-06-08 | 6.1.1 | 1997-07-22 | N/A | Multicolumn indexes, sequences, money data type, GEQO (GEnetic Query Optimizer) |

| 6.2 | 1997-10-02 | 6.2.1 | 1997-10-17 | N/A | JDBC interface, triggers, server programming interface, constraints |

| 6.3 | 1998-03-01 | 6.3.2 | 1998-04-07 | 2003-03-01 | SQL-92 subselect ability, PL/pgTCL |

| 6.4 | 1998-10-30 | 6.4.2 | 1998-12-20 | 2003-10-30 | VIEWs (then only read-only) and RULEs, PL/pgSQL |

| 6.5 | 1999-06-09 | 6.5.3 | 1999-10-13 | 2004-06-09 | MVCC, temporary tables, more SQL statement support (CASE, INTERSECT, and EXCEPT) |

| 7.0 | 2000-05-08 | 7.0.3 | 2000-11-11 | 2004-05-08 | Foreign keys, SQL-92 syntax for joins |

| 7.1 | 2001-04-13 | 7.1.3 | 2001-08-15 | 2006-04-13 | Write-ahead log, outer joins |

| 7.2 | 2002-02-04 | 7.2.8 | 2005-05-09 | 2007-02-04 | PL/Python, OIDs no longer required, internationalization of messages |

| 7.3 | 2002-11-27 | 7.3.21 | 2008-01-07 | 2007-11-27 | Schema, table function, prepared query[130] |

| 7.4 | 2003-11-17 | 7.4.30 | 2010-10-04 | 2010-10-01 | Optimization on JOINs and data warehouse functions[131] |

| 8.0 | 2005-01-19 | 8.0.26 | 2010-10-04 | 2010-10-01 | Native server on Microsoft Windows, savepoints, tablespaces, point-in-time recovery[132] |

| 8.1 | 2005-11-08 | 8.1.23 | 2010-12-16 | 2010-11-08 | Performance optimization, two-phase commit, table partitioning, index bitmap scan, shared row locking, roles |

| 8.2 | 2006-12-05 | 8.2.23 | 2011-12-05 | 2011-12-05 | Performance optimization, online index builds, advisory locks, warm standby[133] |

| 8.3 | 2008-02-04 | 8.3.23 | 2013-02-07 | 2013-02-07 | Heap-only tuples, full text search,[134] SQL/XML, ENUM types, UUID types |

| 8.4 | 2009-07-01 | 8.4.22 | 2014-07-24 | 2014-07-24 | Windowing functions, column-level permissions, parallel database restore, per-database collation, common table expressions and recursive queries[135] |

| 9.0 | 2010-09-20 | 9.0.23 | 2015-10-08 | 2015-10-08 | Built-in binary streaming replication, hot standby, in-place upgrade ability, 64-bit Windows[136] |

| 9.1 | 2011-09-12 | 9.1.24 | 2016-10-27 | 2016-10-27 | Synchronous replication, per-column collations, unlogged tables, serializable snapshot isolation, writeable common table expressions, SELinux integration, extensions, foreign tables[137] |

| 9.2 | 2012-09-10[138] | 9.2.24 | 2017-11-09 | 2017-11-09 | Cascading streaming replication, index-only scans, native JSON support, improved lock management, range types, pg_receivexlog tool, space-partitioned GiST indexes |

| 9.3 | 2013-09-09 | 9.3.25 | 2018-11-08 | 2018-11-08 | Custom background workers, data checksums, dedicated JSON operators, LATERAL JOIN, faster pg_dump, new pg_isready server monitoring tool, trigger features, view features, writeable foreign tables, materialized views, replication improvements |

| 9.4 | 2014-12-18 | 9.4.26 | 2020-02-13 | 2020-02-13 | JSONB data type, ALTER SYSTEM statement for changing config values, ability to refresh materialized views without blocking reads, dynamic registration/start/stop of background worker processes, Logical Decoding API, GiN index improvements, Linux huge page support, database cache reloading via pg_prewarm, reintroducing Hstore as the column type of choice for document-style data.[139] |

| 9.5 | 2016-01-07 | 9.5.23 | 2020-08-13 | 2021-02-11 | UPSERT, row level security, TABLESAMPLE, CUBE/ROLLUP, GROUPING SETS, and new BRIN index[140] |

| 9.6 | 2016-09-29 | 9.6.19 | 2020-08-13 | 2021-11-11 | Parallel query support, PostgreSQL foreign data wrapper (FDW) improvements with sort/join pushdown, multiple synchronous standbys, faster vacuuming of large table |

| 10 | 2017-10-05 | 10.14 | 2020-08-13 | 2022-11-10 | Logical replication,[141] declarative table partitioning, improved query parallelism |

| 11 | 2018-10-18 | 11.9 | 2020-08-13 | 2023-11-09 | Increased robustness and performance for partitioning, transactions supported in stored procedures, enhanced abilities for query parallelism, just-in-time (JIT) compiling for expressions[142][143] |

| 12 | 2019-10-03 | 12.4 | 2020-08-13 | 2024-11-14 | Improvements to query performance and space utilization; SQL/JSON path expression support; generated columns; improvements to internationalization, and authentication; new pluggable table storage interface.[144] |

| 13 | — | 13 Beta 3 | 2020-08-13 | — |

See also

- Comparison of relational database management systems

- Database scalability

- List of databases using MVCC

- LLVM (the JIT engine used by PostgreSQL)

- SQL compliance

References

- "PostgreSQL". Retrieved September 21, 2019.

PostgreSQL: The World's Most Advanced Open Source Relational Database

- "PostgreSQL". Retrieved September 21, 2019.

PostgreSQL: The World's Most Advanced Open Source Relational Database

- "Contributor Profiles". PostgreSQL Global Development Group. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- "Happy Birthday, PostgreSQL!". PostgreSQL Global Development Group. July 8, 2008.

- "PostgreSQL 12.4, 11.9, 10.14, 9.6.19, 9.5.23, and 13 Beta 3 Released!". PostgreSQL. The PostgreSQL Global Development Group. August 13, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- "PostgreSQL: Downloads". Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "License". PostgreSQL Global Development Group. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- "PostgreSQL licence approved by OSI". Crynwr. February 18, 2010. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2010.

- "OSI PostgreSQL Licence". Open Source Initiative. February 20, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- "Debian -- Details of package postgresql in sid". debian.org.

- "Licensing:Main". FedoraProject.

- "PostgreSQL". fsf.org.

- "Audio sample, 5.6k MP3".

- Stonebraker, M.; Rowe, L. A. (May 1986). The design of POSTGRES (PDF). Proc. 1986 ACM SIGMOD Conference on Management of Data. Washington, DC. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- "PostgreSQL: History". PostgreSQL Global Development Group. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Project name – statement from the core team". archives.postgresql.org. November 16, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- "What is PostgreSQL?". PostgreSQL 9.3.0 Documentation. PostgreSQL Global Development Group. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- "OS X Lion Server — Technical Specifications". August 4, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

Web Hosting [..] PostgreSQL

- "Lion Server: MySQL not included". August 4, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- "Mac OS X packages". The PostgreSQL Global Development Group. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Michael Stonebraker – A.M. Turing Award Winner". amturing.acm.org. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

Techniques pioneered in Postgres were widely implemented [..] Stonebraker is the only Turing award winner to have engaged in serial entrepreneurship on anything like this scale, giving him a distinctive perspective on the academic world.

- Stonebraker, M.; Rowe, L. A. The POSTGRES data model (PDF). Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases. Brighton, England: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. pp. 83–96. ISBN 0-934613-46-X.

- Pavel Stehule (June 9, 2012). "Historie projektu PostgreSQL" (in Czech).

- A Brief History of PostgreSQL "Version 3 appeared in 1991 and added support for multiple storage managers, an improved query executor, and a rewritten rule system.". postgresql.org. The PostgreSQL Global Development Group, Retrieved on 18 March 2020.

- "University POSTGRES, Version 4.2". July 26, 1999.

- Page, Dave (April 7, 2015). "Re: 20th anniversary of PostgreSQL ?". pgsql-advocacy (Mailing list). Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Dan R. K. Ports; Kevin Grittner (2012). "Serializable Snapshot Isolation in PostgreSQL" (PDF). Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment. 5 (12): 1850–1861. arXiv:1208.4179. Bibcode:2012arXiv1208.4179P. doi:10.14778/2367502.2367523.

- PostgreSQL 9.1 with synchronous replication (news), H Online

- "Postgres-XC project page" (website). Postgres-XC. Archived from the original on July 1, 2012.

- "Postgres-R: a database replication system for PostgreSQL". Postgres Global Development Group. Archived from the original on March 29, 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Postgres-BDR". 2ndQuadrant Ltd. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- Marit Fischer (November 10, 2007). "Backcountry.com finally gives something back to the open source community" (Press release). Backcountry.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010.

- Bartunov, O; Sigaev, T (May 2011). SP-GiST – a new indexing framework for PostgreSQL (PDF). PGCon 2011. Ottawa, Canada. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- Bartunov, O; Sigaev, T (May 2010). K-nearest neighbour search for PostgreSQL (PDF). PGCon 2010. Ottawa, Canada. Retrieved January 31, 2016.

- "PostgreSQL, the NoSQL Database | Linux Journal". www.linuxjournal.com.

- Geoghegan, Peter (March 23, 2014). "What I think of jsonb".

- "PostgreSQL: Documentation: 9.0: pg_upgrade". www.postgresql.org. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Obe, Regina; Hsu, Leo S. (2012). "10: Replication and External Data". PostgreSQL: Up and Running (1 ed.). Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4493-2633-3. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

Foreign Data Wrappers (FDW) [...] are mechanisms of querying external datasources. PostgreSQL 9.1 introduced this SQL/MED standards compliant feature.

- "libpqxx". Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- "PostgreSQL JDBC Driver". Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- "PostgreSQL + Python | Psycopg". initd.org.

- "node-postgres". Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- "SQL database drivers". Go wiki. golang.org. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- "Rust-Postgres". Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- "Server Programming". Postgresql documentation. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- "DO". Postgresql documentation. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- "PL/Python - Python Procedural Language". Postgresql documentation. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- "Procedural Languages". postgresql.org. March 31, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- Chartier, Colin. "System design hack: Postgres is a great pub/sub & job server". LayerCI blog. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- "Release 9.5". postgresql.org.

- Ringer, Craig. "What is SKIP LOCKED for in PostgreSQL 9.5?". 2nd Quadrant. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- "Add a materialized view relations". March 4, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- "Support automatically-updatable views". December 8, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- "Add CREATE RECURSIVE VIEW syntax". February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- Momjian, Bruce (2001). "Subqueries". PostgreSQL: Introduction and Concepts. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-70331-9. Archived from the original on August 9, 2010. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- Bernier, Robert (February 2, 2006). "Using Regular Expressions in PostgreSQL". O'Reilly Media. Retrieved September 25, 2010.

- "A few short notes about PostgreSQL and POODLE". hagander.net.

- Berkus, Josh (June 2, 2016). "PostgreSQL 9.6 Beta and PGCon 2016". LWN.net.

- "FAQ – PostgreSQL wiki". wiki.postgresql.org. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- "SEPostgreSQL Documentation – PostgreSQL wiki". wiki.postgresql.org.

- "NB SQL 9.3 - SELinux Wiki". selinuxproject.org.

- "PostgreSQL 10 Documentation: Appendix E. Release Notes".

- "Case sensitivity of identifiers". PostgreSQL Global Development Group.

- Berkus, Josh (July 6, 2007). "PostgreSQL publishes first real benchmark". Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- Vilmos, György (September 29, 2009). "PostgreSQL history". Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- "SPECjAppServer2004 Result". SPEC. July 6, 2007. Retrieved July 10, 2007.

- "SPECjAppServer2004 Result". SPEC. July 4, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- "Managing Kernel Resources". PostgreSQL Manual. PostgreSQL.org. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- Greg Smith (October 15, 2010). PostgreSQL 9.0 High Performance. Packt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84951-030-1.

- Robert Haas (April 3, 2012). "Did I Say 32 Cores? How about 64?". Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- Khushi, Matloob (June 2015). "Benchmarking database performance for genomic data". J Cell Biochem. 116 (6): 877–83. doi:10.1002/jcb.25049. PMID 25560631.

- "PostgreSQL: Windows installers". www.postgresql.org. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "postgresql-client-10.5p1 – PostgreSQL RDBMS (client)". OpenBSD ports. October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- "oi_151a Release Notes". OpenIndiana. Retrieved April 7, 2012.

- "AArch64 planning BoF at DebConf". debian.org.

- Souza, Rubens (June 17, 2015). "Step 5 (update): Installing PostgreSQL on my Raspberry Pi 1 and 2". Raspberry PG. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Supported Platforms". PostgreSQL Global Development Group. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- "pgAdmin: PostgreSQL administration and management tools". website. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- "Debian -- Details of package pgadmin3 in jessie". Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- "pgAdmin Development Team". pgadmin.org. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- Dave, Page (December 7, 2014). "The story of pgAdmin". Dave's Postgres Blog. pgsnake.blogspot.co.uk. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "pgAdmin 4 README". Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- phpPgAdmin Project (April 25, 2008). "About phpPgAdmin". Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- PostgreSQL Studio (October 9, 2013). "About PostgreSQL Studio". Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- "TeamPostgreSQL website". October 3, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- oooforum.org (January 10, 2010). "Back Ends for OpenOffice". Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- libreoffice.org (October 14, 2012). "Base features". Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Greg Smith; Robert Treat & Christopher Browne. "Tuning your PostgreSQL server". Wiki. PostgreSQL.org. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- "pgDevOps". BigSQL.org. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Emmanuel Cecchet (May 21, 2009). Building PetaByte Warehouses with Unmodified PostgreSQL (PDF). PGCon 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- "MySpace.com scales analytics for all their friends" (PDF). case study. Aster Data. June 15, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2010. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- "Last Weekend's Outage". Blog. Geni. August 1, 2011.

- "Database". Wiki. OpenStreetMap.

- PostgreSQL affiliates .ORG domain, Australia: Computer World

- W. Jason Gilmore; R.H. Treat (2006). Beginning PHP and PostgreSQL 8: From Novice to Professional. Apress. ISBN 978-1-43020-136-6. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Sony Online opts for open-source database over Oracle, Computer World

- "A Web Commerce Group Case Study on PostgreSQL" (PDF) (1.2 ed.). PostgreSQL.

- "Architecture Overview". Reddit software wiki. Reddit. March 27, 2014. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- Pihlak, Martin. "PostgreSQL @Skype" (PDF). wiki.postgresql.org. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- "How Much Are You Paying For Your Database?". Sun Microsystems blog. 2007. Archived from the original on March 7, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- "Database – MusicBrainz". MusicBrainz Wiki. Retrieved February 5, 2011.

- Duncavage, Daniel P (July 13, 2010). "NASA needs Postgres-Nagios help".

- Roy, Gavin M (2010). "PostgreSQL at myYearbook.com" (talk). USA East: PostgreSQL Conference. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011.

- "Keeping Instagram up with over a million new users in twelve hours". Instagram-engineering.tumblr.com. May 17, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "Postgres at Disqus". Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- Kelly, Matthew (March 27, 2015). At the Heart of a Giant: Postgres at TripAdvisor. PGConf US 2015. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015. (Presentation video)

- "Yandex.Mail's successful migration from Oracle to Postgres [pdf]". Hacker News: news.ycombinator.com. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- S. Riggs; G. Ciolli; H. Krosing; G. Bartolini (2015). PostgreSQL 9 Administration Cookbook - Second Edition. Packt. ISBN 978-1-84951-906-9. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Met Office swaps Oracle for PostgreSQL". computerweekly.com. June 17, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- Oracle Database

- "Open Source Software". FlightAware. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "Ansible at Grofers (Part 2) — Managing PostgreSQL". Lambda - The Grofers Engineering Blog. February 28, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- McMahon, Philip; Chiorean, Maria-Livia; Coleman, Susie; Askoolum, Akash (November 30, 2018). "Digital Blog: Bye bye Mongo, Hello Postgres". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- Alex Williams (April 1, 2013). "Heroku Forces Customer Upgrade To Fix Critical PostgreSQL Security Hole". TechCrunch.

- Barb Darrow (November 11, 2013). "Heroku gussies up Postgres with database roll-back and proactive alerts". GigaOM.

- Craig Kerstiens (September 26, 2013). "WAL-E and Continuous Protection with Heroku Postgres". Heroku blog.

- "EnterpriseDB Offers Up Postgres Plus Cloud Database". Techweekeurope.co.uk. January 27, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- "Alibaba Cloud Expands Technical Partnership with EnterpriseDB". Milestone Partners. September 26, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- O'Doherty, Paul; Asselin, Stephane (2014). "3: VMware Workspace Architecture". VMware Horizon Suite: Building End-User Services. VMware Press Technology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: VMware Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-13-347910-2. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

In addition to the open source version of PostgreSQL, VMware offers vFabric Postgres, or vPostgres. vPostgres is a PostgreSQL virtual appliance that has been tuned for virtual environments.

- Al Sargent (May 15, 2012). "Introducing VMware vFabric Suite 5.1: Automated Deployment, New Components, and Open Source Support". VMware blogs.

- https://www.vmware.com/products/vfabric-postgres.html

- Jeff (November 14, 2013). "Amazon RDS for PostgreSQL – Now Available". Amazon Web Services Blog.

- Alex Williams (November 14, 2013). "PostgreSQL Now Available On Amazon's Relational Database Service". TechCrunch.

- "Amazon Aurora Update – PostgreSQL Compatibility". AWS Blog. November 30, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- "Announcing Azure Database for PostgreSQL". Azure Blog. Retrieved June 19, 2019.

- https://developpaper.com/aliyun-polardb-released-major-updates-to-support-one-click-migration-of-databases-such-as-oracle-to-the-cloud/

- "Asynchronous Master-Slave Replication of PostgreSQL Databases in One Click". DZone. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- "IBM Cloud Hyper Protect DBaaS for PostgreSQL documentation". cloud.ibm.com. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- "Versioning policy". PostgreSQL Global Development Group. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- Vaas, Lisa (December 2, 2002). "Databases Target Enterprises". eWeek. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- Krill, Paul (November 20, 2003). "PostgreSQL boosts open source database". InfoWorld. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- Krill, Paul (January 19, 2005). "PostgreSQL open source database boasts Windows boost". InfoWorld. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- Weiss, Todd R. (December 5, 2006). "Version 8.2 of open-source PostgreSQL DB released". Computerworld. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Gilbertson, Scott (February 5, 2008). "PostgreSQL 8.3: Open Source Database Promises Blazing Speed". Wired. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Huber, Mathias (July 2, 2009). "PostgreSQL 8.4 Proves Feature-Rich". Linux Magazine. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- Brockmeier, Joe (September 30, 2010). "Five Enterprise Features in PostgreSQL 9". Linux.com. Linux Foundation. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- Timothy Prickett Morgan (September 12, 2011). "PostgreSQL revs to 9.1, aims for enterprise". The Register. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- "PostgreSQL: PostgreSQL 9.2 released". www.postgresql.org.

- "Reintroducing Hstore for PostgreSQL". InfoQ.

- Richard, Chirgwin (January 7, 2016). "Say oops, UPSERT your head: PostgreSQL version 9.5 has landed". The Register. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- "PostgreSQL: Documentation: 10: Chapter 31. Logical Replication". www.postgresql.org.

- "PostgreSQL 11 Released". Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- "PostgreSQLRelease Notes". Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- "PostgreSQL: PostgreSQL 12 Released!". www.postgresql.org.

Further reading

- Obe, Regina; Hsu, Leo (July 8, 2012). PostgreSQL: Up and Running. O'Reilly. ISBN 978-1-4493-2633-3.

- Krosing, Hannu; Roybal, Kirk (June 15, 2013). PostgreSQL Server Programming (second ed.). Packt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84951-698-3.

- Riggs, Simon; Krosing, Hannu (October 27, 2010). PostgreSQL 9 Administration Cookbook (second ed.). Packt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84951-028-8.

- Smith, Greg (October 15, 2010). PostgreSQL 9 High Performance. Packt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84951-030-1.

- Gilmore, W. Jason; Treat, Robert (February 27, 2006). Beginning PHP and PostgreSQL 8: From Novice to Professional. Apress. p. 896. ISBN 1-59059-547-5. Archived from the original on July 8, 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2009.

- Douglas, Korry (August 5, 2005). PostgreSQL (second ed.). Sams. p. 1032. ISBN 0-672-32756-2.

- Matthew, Neil; Stones, Richard (April 6, 2005). Beginning Databases with PostgreSQL (second ed.). Apress. p. 664. ISBN 1-59059-478-9. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2009.

- Worsley, John C; Drake, Joshua D (January 2002). Practical PostgreSQL. O'Reilly Media. pp. 636. ISBN 1-56592-846-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to PostgreSQL. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: PostgreSQL |