Pleuromeia

Pleuromeia is an extinct genus of spore plants, assigned to the order Pleuromeiales in some approaches.[1] Pleuromeia dominated vegetation during the Early Triassic all over Eurasia and elsewhere. Its sedimentary context in monospecific assemblages on immature paleosols, is evidence that it was an opportunistic pioneer plant that grew on mineral soils with little competition.[2] It spread to high latitudes with greenhouse climatic conditions following the Permian-Triassic extinction event.[3] Conifers reoccurred in the Early Anisian, followed by the cycads and pteridosperms during the Late Anisian.[4][5]

| Pleuromeia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pleuromeia sternbergi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Lycophytes |

| Class: | Lycopodiopsida |

| Order: | †Pleuromeiales |

| Family: | †Pleuromeiaceae |

| Genus: | †Pleuromeia Corda (1852) |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Lycomeia | |

Description

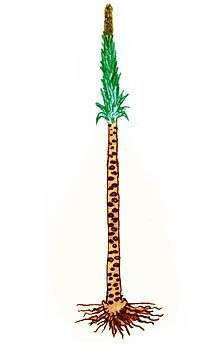

Pleuromeia is an herbaceous plant that lacks secondary tissues and has an unbranched stem of 30 cm long and 2–3 cm wide in the earliest species to around 2 metres long in later species. The stem may have carried small microphylls that are discarded in the lower part of the stem, but may also be leafless, depending on the species or environmental circumstances. It had a 2-4 lobed bulbous base to which numerous adventive roots are attached. Pleuromeia produced a single large cone at the tip of the stem or in some species many smaller cones. The top of the cone carries microsporophylls, the lower part megasporophylls, and both types may intercallated midlength. Sporophylls are disposed from the bottom up. Both types are obovate, with a round to ovoid sporangium and a tongue-like extension nearer to the tip on the upper/inner side. The trilete microspores are hollow, round and 30–40 μm in diameter. Megaspores have a layered outer skin with a small trilete mark, are also hollow, round to ovoid and up to 300–400 μm in diameter.[6] The anatomy of the spores in Pleuromeia is comparable to that of Isoetes and substantiates the assumed close relationship between the Pleuromeiaceae and the Isoetaceae.

Ecology

Dense populations of Pleuromeia hardly allowing for other species, are recorded around the world from habitats ranging from semi-arid to tidal.[7]

Taxonomy

It has been suggested that Sadovnikovia (Kungurian) is the common ancestor of both the Isoetaceae and the Pleuromeiaceae. The earliest species of the extant genus Isoetes is known from the Lower Triassic, its extinct sister genus Annalepis occurs later during the Triassic. The Pleuromeiaceae seems to be represented by the subsequent development of the genera Viatcheslavia (Roadian), Signacularia (Wordian), Pleuromeia (Induan to Anisian) and Ferganodendron (Ladinian–Carnian) from each other.[6]

History of discovery

When the Cathedral of Magdeburg was under repair during the 1830s, a block of sandstone crashed and split open, revealing a fragment of the stem of Pleuromeia sternbergi. This was described by George Graf zu Munster in 1839 as a species of Sigillaria. Corda later assigned the species to the new genus Pleuromeya. The sandstone had been mined in a quarry near Bernburg (Saale) where later on numerous specimens of Pleuromeia were found, including cones. P. sternbergi has since been found in other Lower and Middle Buntsandstein deposits elsewhere in Germany, France and Spain. Other species have been described from several localities in Russia, Australia, South America and Japan.[8]

References

- Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L. & Krings, M. (2009). Paleobotany The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants (2nd ed.). Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-373972-8.

- Retallack, Gregory J. (1997). "Earliest Triassic origin of Isoetes and quillwort evolutionary radiation". Journal of Paleontology. 7 (3): 500–521. doi:10.1017/S0022336000039524.

- Retallack, Gregory J. (2013). "Permian and Triassic greenhouse crises". Gondwana Research. 24: 90–103. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.03.003.

- Grauvogel-Stamm, Léa; Ash, Sidney R. (2005). "Recovery of the Triassic land flora from the end-Permian life crisis". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 4 (6): 593–608. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2005.07.002.

- Zi-qiang, W. (1996), "Recovery of vegetation from the terminal Permian mass extinction in North China", Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology vol. 91, issues 1-4, pp 121-142

- Naugolnykh, Serge V. (2013). "The heterosporous lycopodiophyte Pleuromeia rossica Neuburg, 1960 from the Lower Triassic of the Volga River basin (Russia): organography and reconstruction according to the 'Whole-Plant' concept" (PDF). Wulfenia. 20: 1–16.

- Looy, C.V.; Van Konijnenburg-Van Cittert, J.H.A.; Visscher, H. (2000). "On the ecological success of isoetalean lycopsids after the end-Permian biotic crisis". LPP Contributions. 13: 63–70. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- Bill Chaloner & Geoff Creber Royal Holloway. "An unexpected exposure: Pleuromeia". International Organisation of Palaeobotany. Retrieved 2015-03-19.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)