Plasmacytoma

Plasmacytoma is a plasma cell dyscrasia in which a plasma cell tumour grows within soft tissue or within the axial skeleton.

| Plasmacytoma | |

|---|---|

| |

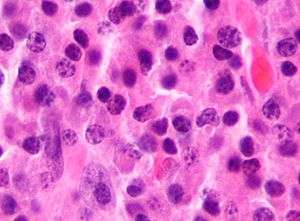

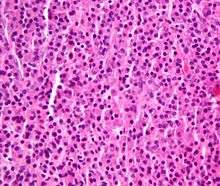

| Micrograph of a plasmacytoma. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

The International Myeloma Working Group lists three types: solitary plasmacytoma of bone (SPB); extramedullary plasmacytoma (EP), and multiple plasmacytomas that are either primary or recurrent.[1] The most common of these is SPB, accounting for 3–5% of all plasma cell malignancies.[2] SPBs occur as lytic lesions within the axial skeleton and extramedullary plasmacytomas most often occur in the upper respiratory tract (85%), but can occur in any soft tissue. Approximately half of all cases produce paraproteinemia. SPBs and extramedullary plasmacytomas are mostly treated with radiotherapy, but surgery is used in some cases of extramedullary plasmacytoma. The skeletal forms frequently progress to multiple myeloma over the course of 2–4 years.[3]

Due to their cellular similarity, plasmacytomas have to be differentiated from multiple myeloma. For SPB and extramedullary plasmacytoma the distinction is the presence of only one lesion (either in bone or soft tissue), normal bone marrow (<5% plasma cells), normal skeletal survey, absent or low paraprotein and no end organ damage.[1]

Signs and symptoms

For SPB the most common presenting symptom is that of pain in the affected bone. Back pain and other consequences of the bone lesion may occur such as spinal cord compression or pathological fracture. Around 85% of extramedullary plasmacytoma presents within the upper respiratory tract mucosa, causing possible symptoms such as epistaxis, rhinorrhoea and nasal obstruction. In some tissues it may be found as a palpable mass.[1][2][3]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of plasmacytoma uses a diverse range of interdisciplinary techniques including serum protein electrophoresis, bone marrow biopsy, urine analysis for Bence Jones protein and complete blood count, plain film radiography, MRI and PET-CT.[4][5]

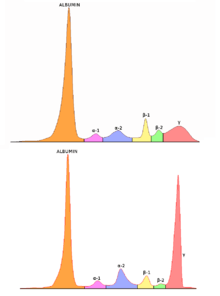

Serum protein electrophoresis separates the proteins in the liquid part of the blood (serum), allowing the analysis of antibodies. Normal blood serum contains a range of antibodies and are said to be polyclonal, whereas serum from a person with plasmacytoma may show a monoclonal spike. This is due to an outgrowth of a single type of plasma cell that forms the plasmacytoma and produces a single type of antibody. The plasma cells are said to be monoclonal and the excessively produced antibody is known as monoclonal protein or paraprotein.[6] Paraproteins are present in 60% of SPB and less than 25% of extramedullary plasmacytoma.[2]

Bone marrow biopsies are performed to ensure the disease is localised; and in SPB or extramedullary plasmacytoma there will not be an increase of monoclonal plasma cells. Tissue biopsies of SPB and extramedullary plasmacytoma are used to assess the phenotype of the plasma cells. Histological analyses can be performed on these biopsies to see what cluster of differentiation (CD) markers are present and to assess monoclonality of the cells. CD markers can aid in the distinction of extramedullary plasmacytoma from lymphomas.[3][7]

Skeletal surveys are used to ensure there are no other primary tumors within the axial skeleton. MRI can be used to assess tumor status and may be advantageous in detecting primary tumors that are not detected by plain film radiography. PET-CT may also be beneficial in detecting extramedullary tumours in individuals diagnosed with SPB. CT imaging may be better than plain film radiography for assessing bone damage.[4][5]

An important distinction to be made is that a true plasmacytoma is present and not a systemic plasma cell disorder, such as multiple myeloma. The difference between plasmacytoma and multiple myeloma is that plasmacytoma lacks increased blood calcium, decreased kidney function, too few red blood cells in the bloodstream, and multiple bone lesions (collectively termed CRAB).[4]

Classification

Plasmacytoma is a tumor of plasma cells. The cells are identical to those seen in multiple myeloma, but they form discrete masses of cells in the skeleton (solitary plasmacytoma of bone; SPB) or in soft tissues (extramedullary plasmacytoma; EP). They do not present with systemic disease, which would classify them as another systemic plasma cell disorder.[8]

The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) has published criteria for the diagnosis of plasmacytomas.[1] They recognise three distinct entities: SPB, extramedullary plasmacytoma and multiple solitary plasmacytomas (+/- recurrent). The proposed criteria for SPB is the presence of a single bone lesion, normal bone marrow (less than 5% plasma cells), small or no paraprotein, no related organ involvement/damage and a normal skeletal survey (other than the single bone lesion). The criteria for extramedullary plasmacytoma are the same but the tumor is located in soft tissue. No bone lesions should be present. Criteria for multiple solitary plasmacytomas (+/- recurrent) are the same except either multiple solitary bone or soft tissue lesions must be present. They may occur as multiple primary tumors or as a recurrence from a previous plasmacytoma.

Association with the Epstein–Barr virus

Rarely, the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is associated with multiple myeloma and plasmacytomas, particularly in individuals who have an immunodeficiency due to e.g. HIV/AIDS, organ transplantation, or a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis.[9] EBV-positive multiple myeloma and plasmacytoma are classified together by the World Health Organization (2016) as Epstein–Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative diseases and termed Epstein–Barr virus-associated plasma cell myeloma. EBV-positivity is more common in plasmacytoma than multiple myeloma. The tissues involved in EBV+ plasmacytoma typically show foci of EBV+ cells with the appearance of rapidly proliferating immature or poorly differentiated plasma cells.[10] These cells express products of EBV genes such as EBER1 and EBER2. EBV-positive plasmacytoma(s) is more likely to progress to multiple myeloma than EBV-negative plasmacytoma(s) suggesting that the virus may play a role in the progression of plasmacytoma to multiple myeloma.[11]

Treatment

Radiotherapy is the main choice of treatment for both SPB and extramedullary plasmacytoma, and local control rates of >80% can be achieved. This form of treatment can be used with curative intent because plasmacytoma is a radiosensitive tumor. Surgery is an option for extramedullary plasmacytoma, but for cosmetic reasons it is generally used when the lesion is not present within the head and neck region.[3][4][7]

Prognosis

Most cases of SPB progress to multiple myeloma within 2–4 years of diagnosis, but the overall median survival for SPB is 7–12 years. 30–50% of extramedullary plasmacytoma cases progress to multiple myeloma with a median time of 1.5–2.5 years. 15–45% of SPB and 50–65% of extramedullary plasmacytoma are disease free after 10 years.[3]

Epidemiology

Plasmacytomas are a rare form of cancer. SPB is the most common form of the disease and accounts for 3-5% of all plasma cell malignancies. The median age at diagnosis for all plasmacytomas is 55. Both SPB and extramedullary plasmacytoma are more prevalent in males; with a 2:1 male to female ratio for SPB and a 3:1 ratio for extramedullary plasmacytoma.[2]

Terminology

There can be some ambiguity when using the word. "Plasmacytoma" is sometimes equated with "plasma cell dyscrasia" or "solitary myeloma".[12] It is often used as part of the phrase "solitary plasmacytoma".[13][14][15] or as part of the phrase "extramedullary plasmacytoma".[16][17] In this context, "extramedullary" means outside of the bone marrow.

See also

- Plasma cell dyscrasia

- Multiple myeloma

- Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS)

- Waldenström's macroglobulinemia

- Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

References

- International Myeloma Working Group (June 2003). "Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group". Br. J. Haematol. 121 (5): 749–57. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04355.x. PMID 12780789.

- Soutar R, Lucraft H, Jackson G, et al. (March 2004). "Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of solitary plasmacytoma of bone and solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma". Br. J. Haematol. 124 (6): 717–26. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04834.x. PMID 15009059.

- Weber DM (2005). "Solitary bone and extramedullary plasmacytoma". Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005: 373–6. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.373. PMID 16304406.

- Kilciksiz S, Karakoyun-Celik O, Agaoglu FY, Haydaroglu A (2012). "A review for solitary plasmacytoma of bone and extramedullary plasmacytoma". ScientificWorldJournal. 2012: 1–6. doi:10.1100/2012/895765. PMC 3354668. PMID 22654647.

- Dimopoulos M, Terpos E, Comenzo RL, et al. (September 2009). "International myeloma working group consensus statement and guidelines regarding the current role of imaging techniques in the diagnosis and monitoring of multiple Myeloma". Leukemia. 23 (9): 1545–56. doi:10.1038/leu.2009.89. PMID 19421229.

- O'Connell TX, Horita TJ, Kasravi B (January 2005). "Understanding and interpreting serum protein electrophoresis". Am Fam Physician. 71 (1): 105–12. PMID 15663032.

- M. Hughes; R. Soutar; H. Lucraft; R. Owen; J. Bird. "Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of solitary plasmacytoma of bone, extramedullary plasmacytoma and multiple solitary plasmacytomas: 2009 update" (PDF). Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Pathology and Genetics of Haemo (World Health Organization Classification of Tumours S.). Oxford Univ Pr. 2003. ISBN 978-92-832-2411-2.

- Sekiguchi Y, Shimada A, Ichikawa K, Wakabayashi M, Sugimoto K, Ikeda K, Sekikawa I, Tomita S, Izumi H, Nakamura N, Sawada T, Ohta Y, Komatsu N, Noguchi M (2015). "Epstein–Barr virus-positive multiple myeloma developing after immunosuppressant therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of literature". International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology. 8 (2): 2090–102. PMC 4396324. PMID 25973110.

- Rezk SA, Zhao X, Weiss LM (June 2018). "Epstein - Barr virus - associated lymphoid proliferations, a 2018 update". Human Pathology. 79: 18–41. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2018.05.020. PMID 29885408.

- Yan J, Wang J, Zhang W, Chen M, Chen J, Liu W (April 2017). "Solitary plasmacytoma associated with Epstein-Barr virus: a clinicopathologic, cytogenetic study and literature review". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. 27: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2016.09.002. PMID 28325354.

- "plasmacytoma" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Dimopoulos MA, Moulopoulos LA, Maniatis A, Alexanian R (September 2000). "Solitary plasmacytoma of bone and asymptomatic multiple myeloma". Blood. 96 (6): 2037–44. doi:10.1182/blood.V96.6.2037. PMID 10979944.

- Di Micco P, Di Micco B (March 2005). "Up-date on solitary plasmacytoma and its main differences with multiple myeloma". Exp. Oncol. 27 (1): 7–12. PMID 15812350. Archived from the original on 2009-01-07.

- Dingli D, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV, et al. (September 2006). "Immunoglobulin free light chains and solitary plasmacytoma of bone". Blood. 108 (6): 1979–83. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-04-015784. PMC 1895544. PMID 16741249.

- Megat Shiraz MA, Jong YH, Primuharsa Putra SH (November 2008). "Extramedullary plasmacytoma in the maxillary sinus" (PDF). Singapore Med J. 49 (11): e310–1. PMID 19037537.

- Bink K, Haralambieva E, Kremer M, et al. (April 2008). "Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma: similarities with and differences from multiple myeloma revealed by interphase cytogenetics". Haematologica. 93 (4): 623–6. doi:10.3324/haematol.12005. PMID 18326524.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |