Rhinorrhea

Rhinorrhea or rhinorrhoea is the free discharge of a thin nasal mucus fluid.[1] The condition, commonly known as a runny nose, occurs relatively frequently. Rhinorrhea is a common symptom of allergies (hay fever) or certain viral infections, such as the common cold. It can be a side effect of crying, exposure to cold temperatures, cocaine abuse[2], or withdrawal, such as from opioids like methadone.[3] Treatment for rhinorrhea is not usually necessary, but there are a number of medical treatments and preventive techniques available.

| Rhinorrhea | |

|---|---|

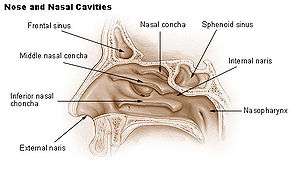

| |

| Labeled cross section of the nasal cavities | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology |

The term was coined in 1866 and is a combination of the Greek terms rhino- ("of the nose") and -rhoia ("discharge" or "flow").[4]

Signs and symptoms

Rhinorrhea is characterized by an excess amount of mucus produced by the mucous membranes that line the nasal cavities. The membranes create mucus faster than it can be processed, causing a backup of mucus in the nasal cavities. As the cavity fills up, it blocks off the air passageway, causing difficulty breathing through the nose. Air caught in nasal cavities, namely the sinus cavities, cannot be released and the resulting pressure may cause a headache or facial pain. If the sinus passage remains blocked, there is a chance that sinusitis may result.[5] If the mucus backs up through the Eustachian tube, it may result in ear pain or an ear infection. Excess mucus accumulating in the throat or back of the nose may cause a post-nasal drip, resulting in a sore throat or coughing.[5] Additional symptoms include sneezing, nosebleeds, and nasal discharge.[6]

Causes

Cold temperature

Rhinorrhea is especially common during winter months and certain low temperature seasons. Cold-induced rhinorrhea occurs due to a combination of thermodynamics and the body's natural reactions to cold weather stimuli. One of the purposes of nasal mucus is to warm inhaled air to body temperature as it enters the body. In order for this to happen, the nasal cavities must be constantly coated with liquid mucus. During cold, dry seasons, the mucus lining nasal passages tends to dry out, meaning that mucous membranes must work harder, producing more mucus to keep the cavity lined. As a result, the nasal cavity can fill up with mucus. At the same time, when air is exhaled, water vapor in breath condenses as the warm air meets the colder outside temperature near the nostrils. This causes an excess amount of water to build up inside nasal cavities. In these cases, the excess fluid usually spills out externally through the nostrils.[7]

Infection

Rhinorrhea can be a symptom of other diseases, such as the common cold or influenza. During these infections, the nasal mucous membranes produce excess mucus, filling the nasal cavities. This is to prevent infection from spreading to the lungs and respiratory tract, where it could cause far worse damage.[8] It has also been suggested that rhinorrhea is a result of viral evolution, and may be a response that is not useful to the host, but which has evolved by the virus to maximise its own infectivity.[9] Rhinorrhea caused by these infections usually occur on circadian rhythms.[10] Over the course of a viral infection, sinusitis (the inflammation of the nasal tissue) may occur, causing the mucous membranes to release more mucus. Acute sinusitis consists of the nasal passages swelling during a viral infection. Chronic sinusitis occurs when one or more nasal polyps appear. This can be caused by a deviated septum as well as a viral infection.[11]

Allergies

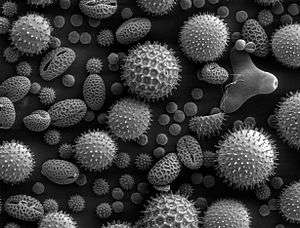

Rhinorrhea can also occur when individuals with allergies to certain substances, such as pollen, dust, latex, soy, shellfish, or animal dander, are exposed to these allergens. In people with sensitized immune systems, the inhalation of one of these substances triggers the production of the antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE), which binds to mast cells and basophils. IgE bound to mast cells are stimulated by pollen and dust, causing the release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine.[12] In turn, this causes, among other things, inflammation and swelling of the tissue of the nasal cavities as well as increased mucus production. Particulate matter in polluted air and chemicals such as chlorine and detergents, which can normally be tolerated, can make the condition considerably worse.

Crying

Rhinorrhea is also associated with shedding tears (lacrimation), whether from emotional events or from eye irritation. When excess tears are produced, the liquid drains through the inner corner of the eyelids, through the nasolacrimal duct, and into the nasal cavities. As more tears are shed, more liquid flows into the nasal cavities, both stimulating mucus production and hydrating any dry mucus already present in the nasal cavity. The buildup of fluid is usually resolved via mucus expulsion through the nostrils.[8]

Head trauma

If caused by a head injury, rhinorrhea can be a much more serious condition. A basilar skull fracture can result in a rupture of the barrier between the sinonasal cavity and the anterior cranial fossae or the middle cranial fossae. This rupture can cause the nasal cavity to fill with cerebrospinal fluid. This condition, known as cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea or CSF rhinorrhea, can lead to a number of serious complications and possibly death if not addressed properly.[13]

Other causes

Rhinorrhea can occur as a symptom of opioid withdrawal accompanied by lacrimation.[14] Other causes include cystic fibrosis, whooping cough, nasal tumors, hormonal changes, and cluster headaches. Due to changes in clinical practice, Rhinorrhea is now reported as a frequent side effect of oxygen-intubation during colonoscopy procedures [A simple, innovative way to reduce rhinitis symptoms after sedation during endoscopy" by Nai-Liang Li, et al., Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology, 2011, Feb; volume 25(2): pages 68–72.]. Rhinorrhea can also be the side effect of several genetic disorders, such as primary ciliary dyskinesia.[11]

Treatment

In most cases, treatment for rhinorrhea is not necessary since it will clear up on its own—especially if it is the symptom of an infection. For general cases nose-blowing can get rid of the mucus buildup. Though blowing may be a quick-fix solution, it would likely proliferate mucosal production in the sinuses, leading to frequent and higher mucus buildups in the nose. Alternatively, saline nasal sprays and vasoconstrictor nasal sprays may also be used, but may become counterproductive after several days of use, causing rhinitis medicamentosa.

In recurring cases, such as those due to allergies, there are medicinal treatments available. For cases caused by histamine buildup, several types of antihistamines can be obtained relatively cheaply from drugstores.

People who prefer to keep clear nasal passages, such as singers, who need a clear nasal passage to perform, may use a technique called nasal irrigation to prevent rhinorrhea. Nasal irrigation involves rinsing the nasal cavity regularly with salty water or commercial saline solutions.[15]

References

- Dorland's pocket medical dictionary. Elsevier. p. 660. ISBN 978-81-312-3501-0.

- Myon L, Delforge A, Raoul G, Ferri J (February 2010). "[Palatal necrosis due to cocaine abuse]". Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac (in French). 111 (1): 32–5. doi:10.1016/j.stomax.2009.01.009. PMID 20060991.

- Eileen Trigoboff; Kneisl, Carol Ren; Wilson, Holly Skodol (2004). Contemporary psychiatric-mental health nursing. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson/Prentice Hall. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-13-041582-0.

- "Rhinorrhea". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Nasal discharge". Medline Plus. United States National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- "Rhinorrhea Overview". FreeMd. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Why Does Cold Weather Cause Runny Noses?". NPR. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Why Does My Nose Run?". Kids Health. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Vareille M, Kieninger E, Edwards MR, Regamey N (January 2011). "The airway epithelium: soldier in the fight against respiratory viruses". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24 (1): 210–29. doi:10.1128/CMR.00014-10. PMC 3021210. PMID 21233513.

- Smolensky MH, Reinberg A, Labrecque G (May 1995). "Twenty-four Hour Pattern in Symptom Intensity of Ciral and Allergic Rhinitis: Treatment Implications". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 95 (5 Pt 2): 1084–96. doi:10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70212-1. PMC 7126948. PMID 7751526.

- "Rhinorrhea – Definition, Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment". Prime Health Channel. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- Dipiro, J.T.; Talbert, R.L.; Yee, G.C. (2008). Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach (7th ed.). New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. pp. 1565–1575. ISBN 978-0-07-147899-1.

- Welch; et al. (22 July 2011). "CSF Rhinorrhea". Medscape. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Opioid Withdrawal Protocol" (PDF). Mental Health and Addiction Services. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- Aubrey, Allison (22 February 2007). "Got a Runny Nose? Flush it Out!". NPR. Retrieved 21 September 2011.