Undercover operation

To go "undercover" is to avoid detection by the entity one is observing, and especially to disguise one's own identity or use an assumed identity for the purposes of gaining the trust of an individual or organization to learn or confirm confidential information or to gain the trust of targeted individuals in order to gather information or evidence. Traditionally, it is a technique employed by law enforcement agencies or private investigators, and a person who works in such a role is commonly referred to as an undercover agent.

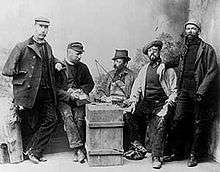

History

Undercover work has been used in a variety of ways throughout the course of history, but the first organized, but informal, undercover program was first employed in France by Eugène François Vidocq in the early 19th century, from the late First Empire through most of the Bourbon Restoration. At the end of 1811, Vidocq set up an informal plainclothes unit, the Brigade de la Sûreté ("Security Brigade"), which was later converted to a security police unit under the Prefecture of Police. The Sûreté initially had eight, then twelve, and, in 1823, twenty employees. One year later, it expanded again, to 28 secret agents. In addition, there were eight people who worked secretly for the Sûreté, but instead of a salary, they received licences for gambling halls. A major portion of Vidocq's subordinates were ex-criminals like himself.[1]

Vidocq personally trained his agents, for example, in selecting the correct disguise based on the kind of job. He himself still went out hunting for criminals too. His memoirs are full of stories about how he outsmarted crooks by pretending to be a beggar or an old cuckold. At one point, he even simulated his own death.[2]

In England, the first modern police force was established in 1829 by Sir Robert Peel as the Metropolitan Police of London. From the start, the force occasionally employed plainclothes undercover detectives, but there was much public anxiety that these powers were being used for the purpose of political repression. In part due to these concerns, the 1845 official Police Orders required all undercover operations to be specifically authorized by the superintendent. It was only in 1869 that Police commissioner Edmund Henderson established a formal plainclothes detective division.[3]

The first Special Branch of police was the Special Irish Branch, formed as a section of the Criminal Investigation Department of the MPS in London in 1883, initially to combat the bombing campaign that the Irish Republican Brotherhood had begun a few years earlier. This pioneering branch was the first to be trained in counter terrorism techniques.

Its name was changed to Special Branch as it had its remit gradually expanded to incorporate a general role in counter terrorism, combating foreign subversion and infiltrating organized crime. Law enforcement agencies elsewhere established similar Branches.[4]

In the United States, a similar route was taken with the establishment of the Italian Squad in 1906 by the New York City Police Department under police commissioner William McAdoo to combat rampant crime and intimidation in the poor Italian neighborhoods.[5] Various federal agencies began their own undercover programs shortly afterwards – the Federal Bureau of Investigation was founded in 1908.[6][7]

Risks

There are two principal problems that can affect agents working in undercover roles. The first is the maintenance of identity and the second is the reintegration back into normal duty.

Living a double life in a new environment presents many problems. Undercover work is one of the most stressful jobs a special agent can undertake.[8] The largest cause of stress identified is the separation of an agent from friends, family and his normal environment. This simple isolation can lead to depression and anxiety. There is no data on the divorce rates of agents, but strain on relationships does occur. This can be a result of a need for secrecy and an inability to share work problems, and the unpredictable work schedule, personality and lifestyle changes and the length of separation can all result in problems for relationships.[9]

Stress can also result from an apparent lack of direction of the investigation or not knowing when it will end. The amount of elaborate planning, risk, and expenditure can pressure an agent to succeed, which can cause considerable stress.[10] The stress that an undercover agent faces is considerably different from his counterparts on regular duties, whose main source of stress is the administration and the bureaucracy.[11] As the undercover agents are removed from the bureaucracy, it may result in another problem. The lack of the usual controls of a uniform, badge, constant supervision, a fixed place of work, or (often) a set assignment could, combined with their continual contact with the organized crime, increase the likelihood for corruption.[10]

This stress may be instrumental in the development of drug or alcohol abuse in some agents. They are more prone to the development of an addiction as they suffer greater stress than other police, they are isolated, and drugs are often very accessible.[10] Police, in general, have very high alcoholism rates compared to most occupational groups, and stress is cited as a likely factor.[10] The environment that agents work in often involves a very liberal exposure to the consumption of alcohol,[12] which in conjunction with the stress and isolation could result in alcoholism.

There can be some guilt associated with going undercover due to betraying those who have come to trust the officer. This can cause anxiety or even, in very rare cases, sympathy with those being targeted. This is especially true with the infiltration of political groups, as often the agent will share similar characteristics with those they are infiltrating like class, age, ethnicity or religion. This could even result in the conversion of some agents.[9]

The lifestyle led by undercover agents is very different compared to other areas in law enforcement, and it can be quite difficult to reintegrate back into normal duties. Agents work their own hours, they are removed from direct supervisory monitoring, and they can ignore the dress and etiquette rules.[13] So resettling back into the normal police role requires the shedding of old habits, language and dress. After working such free lifestyles, agents may have discipline problems or exhibit neurotic responses. They may feel uncomfortable, and take a cynical, suspicious or even paranoid world view and feel continually on guard.[10] Other risks include capture, death and torture.

Plainclothes law enforcement

Undercover agents should not be confused with law enforcement officers who wear plainclothes. This method is used by law enforcement and intelligence agencies. To wear plainclothes is to wear civilian clothes, instead of wearing a uniform, to avoid detection or identification as a law enforcement officer. However, plainclothes police officers typically carry normal police equipment and normal identification. Police detectives are assigned to wear plainclothes by wearing suits or formal clothes instead of the uniform typically worn by their peers. Police officers in plainclothes must identify themselves when using their police powers; however, they are not required to identify themselves on demand and may lie about their status as a police officer in some situations (see sting operation).

Sometimes, police might drive an unmarked vehicle or a vehicle which looks like a taxi. [14]

Controversies

| Further information | Country | Approximate time period | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATF fictional sting operations | USA | ? - 2014 | Government agents enticed targeted victims and incited them to commit crimes of a type and scale calculated to procure specific sentences, for which they would then be prosecuted and jailed, typically for around 15 years. |

| UK undercover policing relationships scandal | UK | ? - 2010 | Undercover officers infiltrating protest groups, deceived protesters into long-term relationships and in some cases, fathered children with them on false pretences, only to vanish later without explanation. Units disbanded and unreserved apology given as part of settlement, noting that the women had been deceived. Legal action continues as of 2016, and a public inquiry examining officer conduct, the Undercover Policing Inquiry, is underway. |

See also

- America Undercover – television series

- Covert operation

- Covert policing in the United Kingdom

- Donnie Brasco – undercover police officer

- Paul Manning – undercover police officer

- Bob Lambert – undercover police officer

- Undercovers – television series

- Fauda – television series

References

- Hodgetts, Edward A. (1928). Vidocq. A Master of Crime. London: Selwyn & Blount.

- Morton, James (2004), The First Detective: The Life and Revolutionary Times of Vidocq (in German), Ebury Press, ISBN 978-0-09-190337-4

- Mitchel P. Roth, James Stuart Olson (2001). Historical Dictionary of Law Enforcement. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-313-30560-3.

- Tim Newburn, Peter Neyroud (2013). Dictionary of Policing. Routledge. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-134-01155-1.

- Anne T. Romano (2010). Italian Americans in Law Enforcement. Xlibris Corporation. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4535-5882-9.

- Marx, G. (1988). Undercover: Police Surveillance In America. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Anne T. Romano (11 November 2010). Italian Americans in Law Enforcement. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-4535-5882-9. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Girodo, M. (1991). Symptomatic reactions to undercover work. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179 (10), 626-630.

- Marx, G. (1988). Undercover: Police Surveillance In America. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Marx, G. (1988). Undercover: Police Surveillance In America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Brown, Jennifer; Campbell, Elizabeth (October 1990). "Sources of occupational stress in the police". Work & Stress. 4 (4): 305–318. doi:10.1080/02678379008256993.

- Girodo, M. (1991). Drug corruptions in undercover agents: Measuring the risks. Behavioural Science and the Law, 9, 361-370.

- Girodo, M. (1991). Personality, job stress, and mental health in undercover agents. Journal of Social Behaviour and Personality, 6 (7), 375-390.

- Code3Paris. "Unmarked Police Cars Responding Compilation: Sirens NYPD Police Taxi, Federal Law Enforcement, FDNY" – via YouTube.

Further reading

Documentaries

- Channel 4 (2011). Confessions of an Undercover Cop. Documentary about Mark Kennedy (policeman).

- Jeans, Chris (Director and Producer) & Russell, Mike (Narrator) (1988). "Confessions of an Undercover Cop". America Undercover. HBO.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) Documentary featuring the work of ex-cop Mike Russell, whose undercover work for the New Jersey State Police led to the arrests of over 41 members of the Genovese crime family, and of corrupt prison officials and a state senator

Print

- Hattenstone, Simon (March 25, 2011). "Mark Kennedy: Confessions of an undercover cop". The Guardian.

- Russell, Mike & Picciarelli, Patrick W. (August 6, 2013). Undercover Cop: How I Brought Down the Real-Life Sopranos (First ed.). Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-1-250-00587-8.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Whited, Charles (1973). The Decoy Man: The Extraordinary Adventures of an Undercover Cop. Playboy Press/Simon & Schuster. ASIN B0006CA0QG.