Phytelephas seemannii

Phytelephas seemannii, commonly called Panama ivory palm, is a species of flowering plant in the family Arecaceae. It is one of the plants used for vegetable ivory.

| Phytelephas seemannii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of parts of Phytelephas ruizii, likely Phytelephas seemannii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Genus: | Phytelephas |

| Species: | P. seemannii |

| Binomial name | |

| Phytelephas seemannii | |

| Subspecies[3] | |

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Names

The species epithet seemannii honors botanist Berthold Carl Seemann who collected some of the first specimens, including the lectotype.[4] In Spanish it is called cabeza de negra (black head), palma de marfil (ivory palm), and tagua.[5] In Colombian Spanish it is additionally known as allagua.[5] In Cuna it is sam,[3] or sagu.[5] In both the Quechua[3] and Choco languages it is called anta.[5]

Habitat

Phytelephas seemannii is native to Colombia and Panama, with much of it growing in shaded areas by rivers in lowland rainforest in Colombia's Pacific/Chocó natural region.[1][4] It is usually found at elevations from 0–1,000 metres (0–3,281 ft) in semi-deciduous forests.[3]

Subspecies

Phytelephas seemannii has two subspecies, P. s. ssp. brevipes and P. s. ssp. seemannii.[3] P. s. ssp. brevipes is endemic to the upper Mamoní Valley in Panama, at or below 500 metres (1,600 ft) in elevation, and may be a hybrid of P. seemannii and P. macrocarpa.[3]

Description

Phytelephas seemannii most closely resembles Phytelephas macrocarpa.[2] However, the former has leaves that have fewer pinnae which are larger.[2] Its trunk is also not upright but "creeping" and decumbent.[2] The tree is generally less than 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) tall, with inflorescences below the 0.5 metres (1 ft 8 in) mark.[6] Its spathes are double instead of in threes or fours.[2] On the male flowers are only 36 stamens and not the hundreds of other species.[2] The heads contain fewer fruits than other species, but inside are more nuts that are larger.[2] Typically each fruit has 5 seeds protected by a 1 centimetre (0.39 in) fibrous coat, and each inflorescence has up to 8 fruits.[6] Each tree can have dozens of inflorescences at a time.[6]

In immature seeds, the endosperm is a liquid, like in a coconut, and then later it hardens as the fruit wall softens and deteriorates.[6]

Ecology

Panama ivory palm trees flower after the end of the dry season, between February and May.[7] The flowers are pollinated by insects, specifically by two types of rove beetles, pollen-eating Amazoncharis spp. and their predators in the genus Xanthopygus.[7] The Amazoncharis beetles hollow out egg chambers within the male inflorescence, similar to how beetles in the related subtribe Gyrophaenina do inside of mushrooms.[7] Squirrels and agoutis will eat the fleshy inner mesocarp surrounding the endocarp of the fruit, but do not eat the extremely hard endosperm.[6] The rock-hard endosperm also makes the seed immune from most insect pests.[6] Seed dispersers include the Central American agouti (Dasyprocta punctata),[6] and lowland paca (Agouti paca).[8][6]

Uses

The seeds are traded at a regional international level as vegetable ivory,[1] which is also called tagua. This commercial use is a threat to the species, but progress is being made on using more sustainable practices and conservation.[1] As the tree typically grows only 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) tall, it fortunately was not chopped down to harvest the seeds as was done with Phytelephas aequatorialis at the peak of tagua harvesting.[6]

The jelly-like liquid in the immature seeds, which later turns into the vegetable ivory, is edible.[5] Occasionally in the marketplaces of Guna Yala the thin crust surrounding the ivory is sold as food.[5]

In Colombia the fronds are sometimes used for thatch.[5]

References

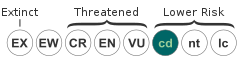

- Bernal, Rodrigo (1 January 1998). "Phytelephas seemannii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1 January 1998. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T38636A10141062.en. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017.

- Cook, Orator F.; Pinel, Pablo (31 May 1912). Rockwell, J.E. (ed.). "Seeds and Plants Imported During the Period from April 1 to June 30 1911 Inventory No 26 Nob 30462 to 31370". Bulletin of the Bureau of Plant Industry (242): 68. OCLC 1716991.

- Barfod, Anders S. (1991). A monographic study of the subfamily Phytelephantoideae (Arecaceae). Opera Botanica. 105. pp. 1–73. ISBN 9788788702514. OCLC 488691909.

- Arecaceae Phytelephas seemannii O.F.Cook. International Plant Names Index. 242. 30 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

Distribution: Chocó (Colombia, Western South America, Southern America) Type Information Collector(s): B.C.Seemann s.n. 1847 Type Location: lectotype BM

- Duke, James A. (1986). Isthmian Botanical Dictionary. Journal of Economic and Taxonomic Botany Additional Series. 3 (3rd ed.). Jodhpur, India: Scientific Publishers. p. 149. ISBN 978-8185046358. OCLC 475457456.

- Dalling, J. W.; Harms, K. E.; Eberhard, J. R.; Candanedo, I. (1996). "Natural History and Uses of Tagua (Phytelephas seemannii) in Panama" (PDF). Principes. 40 (1): 16–23. OCLC 194618633. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-29. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- Bernal, Rodrigo; Ervik, Finn (December 1996). "Floral Biology and Pollination of the Dioecious Palm Phytelephas seemannii in Colombia: An Adaptation to Staphylinid Beetles" (PDF). Biotropica. 28 (4B): 682–896. doi:10.2307/2389054. JSTOR 2389054. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- Zona, Scott; Henderson, Andrew (January 1989). "A review of animal-mediated seed dispersal of palms". Selbyana. 11: 6–21. JSTOR 41759760.

External links