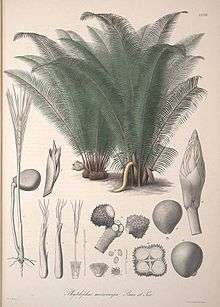

Phytelephas macrocarpa

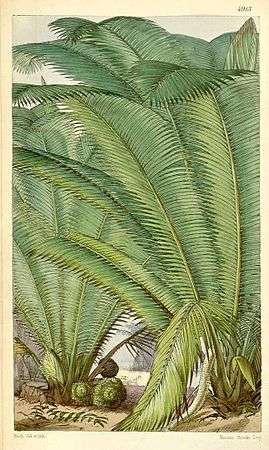

Phytelephas macrocarpa is a single-stemmed, unarmed, reclining or erect palm from the extreme northern coastal regions of South America, growing to some 12 m tall. It has been introduced and cultivated in tropical regions all over the world. The trunk is about 30 cm across, with prominent leaf scars. The crown is made up of about 30 plume-like leaves or fronds, each about 8 m long, dead leaves being persistent. It is one of some 7 species of palm in the genus Phytelephas, all of which have been exploited for vegetable ivory or tagua from the seed or corozo nut. The closely related Ammandra decasperma from Colombia, and Aphandra natalia from Ecuador, are also sources of vegetable ivory, but of inferior quality and therefore not commercially significant. 'Phytelephas macrocarpa' translates to ‘elephant plant’ with 'large fruit', the endosperm of the nut having the texture of elephant ivory, and consisting of large, thick-walled cells of two long-chain polysaccharides, mannan A and B.[1][2]

| Phytelephas macrocarpa | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Genus: | Phytelephas |

| Species: | P. macrocarpa |

| Binomial name | |

| Phytelephas macrocarpa | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

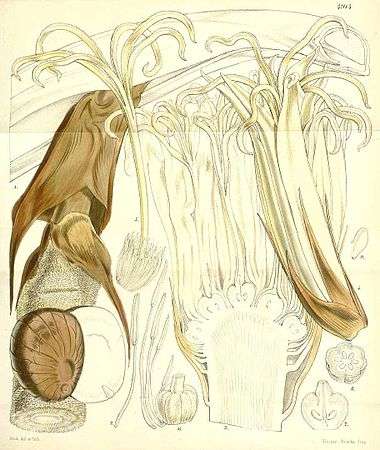

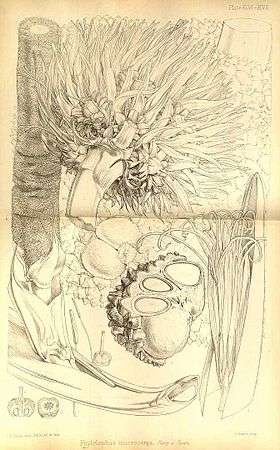

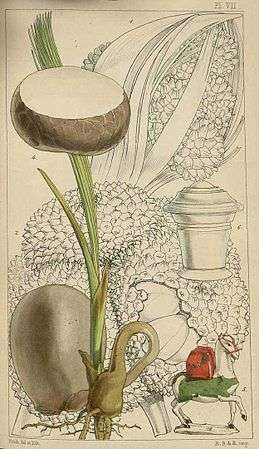

The species is dioecious, male and female flowers growing on different trees. Flowering and fruiting are not seasonal, but take place throughout the year. Flowers form among the leaves, and in bud are enclosed in two sheaths. Male and female flowers differ greatly in shape and structure, the male inflorescence being long, cylindrical, fleshy, and spike-like, up to 150 cm long, while the female inflorescence is club-shaped and 40–50 cm long. The fruiting head is near-spherical and up to 30 cm in diameter, usually with about 15–20 closely set fruits which are conical, 10–15 cm in diameter, and five- to six-angled by the pressure of growth. The outer husk is thick and woody with numerous sharp spines; the mesocarp is thin, fleshy, oily and yellowish-orange in colour. Each fruit houses 5 or 6 seeds of about 5 × 3 cm, these normally being wedge-shaped, though quite variable in both size and shape; the endosperm is homogeneous, and liquid at first, becoming gelatinous later and finally extremely hard, white and ivory-like, occasionally with a small central cavity.

The genus Phytelephas is essentially northern South American and grows along the Caribbean coastal lowlands of Colombia and Panama, and the Pacific coastal lowlands of Ecuador and Peru. Phytelephas species usually occur on low-altitude alluvial soils in river valleys where soil temperatures are greater than 18 °C, but P. macrocarpa can also be found up to some 1,200 m altitude. All species prefer humid and shady areas, and rainfall exceeding 2,500 mm per year, though P. macrocarpa is also found on dry, steep slopes in northeastern Colombia. On seasonal floodplains Phytelephas forms large stands known as taguales in Colombia and Ecuador - flooding rivers distribute the heavy seeds along the floodplains. Rodents, such as pacas (Agouti paca) and agoutis (Dasyprocta), eat the fleshy mesocarp, carrying the seeds in and beyond the floodplains.

Utilisation

When ripe, the fruit which has formed on the female tree, breaks apart and the woody epicarp covered in spines disintegrates, allowing the nuts to fall to the ground. Their orange fleshy mesocarp covering is eaten by rodents and some nuts are buried in caches. Nuts are collected from the ground, and taken for processing in sacks or baskets. The principal use of the tagua palm is of the vegetable ivory of its seeds. This is hard and dense with an attractive cream colour, which, on polishing, compares favourably with true ivory. Tagua softens when soaked, dissolving completely when immersed in water for long periods, but recovering its hardness on drying. The contents of the immature fruit are liquid, with a sweet flavour and used as a - refreshing drink. The fronds are used as thatching for native huts. The nuts polish and dye readily, being used for a large variety of items. Its most lucrative use was for the production of buttons for the clothing industry.[3]

First records of tagua production are for 1840-1841 when it made up a negligible fraction of Colombian exports. From the 1860s tagua harvesting picked up and became a major forest product of both Colombia and Ecuador. In the 1920s, during a peak in trade, exports from Ecuador amounted to some 25 000 tonnes, and some 20% of all buttons made in the United States were of tagua. At about the same time exports from Colombia declined because of the increasing use of plastics, disappearing altogether by 1935. Ecuador followed after 1941, and tagua trade had all but disappeared by 1945. The industry never became extinct, however, and survived in Riobamba in Ecuador and in Chiquinquirá in Colombia, as a minor business producing souvenirs, and exporting to Japan, West Germany, and Italy.

In 1990 an initiative by Conservation International started linking tagua producers in rainforest areas with international markets. Clothing companies in the United States supported the program by buying a first lot of one million buttons, with other companies soon joining the program. Profits are invested in conservation and sustainable development programs in tagua production regions - these being the Santiago River basin in Ecuador, and the Pacific coast of NW Colombia. Community involvement in tagua harvesting promises an attractive economic arrangement leading to forest conservation by the local populace. A global antipathy to the trade in elephant ivory has led to renewed interest in the sustainable resource of vegetable ivory. Tagua is becoming sought after for small carvings and for use in jewelry such as watches, earrings, bracelets, and necklaces. The nut is a nutritious food when ground up.

Associated insects

Large weevil larvae, similar and perhaps identical to Rhynchophorus palmarum, tunnel into the stems of tagua and are the vectors of a nematode, Bursaphelenchus cocophilus, afflicting cultivated palms. Various species of bee, beetle and fly visit the flowers, but beetles are considered the most effective pollinators.[4]

Gallery

References

- Paton, F. J.; Nanji, D. R.; Ling, A. R. (1924). "On the hydrolysis of the endosperm of Phytelephas macrocarpa by its own enzymes". Biochemical Journal. 18 (2): 451–4. doi:10.1042/bj0180451. PMC 1259438. PMID 16743327.

- Aspinall, G. O.; Hirst, E. L.; Percival, E. G. V.; Williamson, I. R. (1953). "635. The mannans of ivory nut (Phytelephas macrocarpa). Part I. The methylation of mannan A and mannan B". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed). 18 (2): 3184–3188. doi:10.1042/bj0180451. PMC 1259438. PMID 16743327.

- R.G. Bernal & G. Galeano (May 1993). Selected species and strategies to enhance income generation from Amazonian forests - Tagua (Phytelephas aequatorialis, Palmae) (Report). FAO. pp. 213–222. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Janick, Jules; Paull, Robert (2008). The Encyclopedia of Fruit and Nuts. Wallingford, UK: CABI.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phytelephas macrocarpa. |