Pheneus

Pheneus or Pheneos (Ancient Greek: Φένεος[1] or Φενεός[2]) was a town in the northeast of ancient Arcadia. Its territory, called Pheniatis (ἡ Φενεατική[3] or ἡ Φενεᾶτις[4] or η Φενική),[5] was bounded on the north by that of the Achaean towns of Aegeira and Pellene, east by the Stymphalia, west by the Cleitoria, and south by the Caphyatis and Orchomenia. This territory is shut in on every side by lofty mountains, offshoots of Mount Cyllene and the Aroanian chain; and it is about 7 miles (12 km) in length and the same in breadth. Two streams descend from the northern mountains, and unite their waters about the middle of the valley; the united river bore in ancient times the name of Olbius and Aroanius.[3] There is no opening through the mountains on the south; but the waters of the united river are carried off by subterranean channels (katavóthra) in the limestone rocks, and, after flowing underground, reappear as the sources of the river Ladon. In order to convey the waters of this river in a single channel to the katavóthra, the inhabitants at an early period constructed a canal, 50 stadia in length, and 30 feet (9 m) in breadth.[3][6] This great work, which was attributed to Heracles, had become useless in the time of Pausanias, and the river had resumed its ancient and irregular course; but traces of the canal of Heracles are still visible, and one bank of it was a conspicuous object in the valley when it was visited by William Martin Leake in 1806. The canal of Heracles, however, could not protect the valley from the danger to which it was exposed, in consequence of the katavóthra becoming obstructed, and the river finding no outlet for its waters. The Pheneatae related that their city was once destroyed by such an inundation, and in proof of it they pointed out upon the mountains the marks of the height to which the water was said to have ascended.[7] Pausanias evidently refers to the yellow border which is still visible upon the mountains and around the plain: but in consequence of the great height of this line upon the rocks, it is difficult to believe it to be the mark of the ancient depth of water in the plain, and it is more probably caused by evaporation; the lower parts of the rock being constantly moistened, while the upper are in a state of comparative dryness, thus producing a difference of colour in process of time. It is, however, certain that the Pheneatic plain has been exposed more than once to such inundations. Pliny the Elder says that the calamity had occurred five times;[8] and Eratosthenes related a memorable instance of such an inundation through the obstruction of the katavóthra, when, after they were again opened, the water rushing into the Ladon and the Alpheius overflowed the banks of those rivers at Olympia.[9] The account of Eratosthenes has been confirmed by a similar occurrence in modern times. In 1821 the katavóthra became obstructed, and the water continued to rise in the plain till it had destroyed 7 to 8 square miles (18 to 21 km2) of cultivated country. Such was its condition till 1832, when the subterraneous channels again opened, the Ladon and Alpheius overflowed, and the plain of Olympia was inundated. Other ancient writers allude to the katavóthra and subterraneous course of the river of Pheneus.[10]

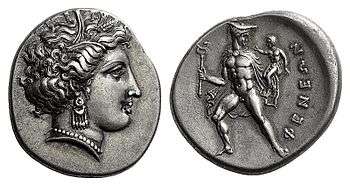

Pheneus is mentioned by Homer in the Catalogue of Ships in the Iliad,[1] and was more celebrated in mythical than in historical times. Virgil represents it as the residence of Evander;[11] and its celebrity in mythical times is indicated by its connection with Heracles. Pausanias found the city in a state of complete decay. The acropolis contained a ruined temple of Athena Tritonia, with a brazen statue of Poseidon Hippius. On the descent from the acropolis was the stadium; and on a neighbouring hill, the sepulchre of Iphicles, the brother of Heracles. There was also a temple of Hermes, who was the principal deity of the city.[12]

The lower slope of the mountain, upon which the remains of Pheneus stand, is occupied by a village now called Archaia Feneos. There is, however, some difficulty in the description of Pausanias compared with the existing site. Pausanias says that the acropolis was precipitous on every side, and that only a small part of it was artificially fortified; but the summit of the insulated hill, upon which the remains of Pheneus are found, is too small apparently for the acropolis of such an important city, and moreover it has a regular slope, though a very rugged surface. Hence Leake supposes that the whole of this hill formed the acropolis of Pheneus, and that the lower town was in a part of the subjacent plain; but the entire hill is not of that precipitous kind which the description of Pausanias would lead one to suppose, and it is not impossible that the acropolis may have been on some other height in the neighbourhood, and that the hill on which the ancient remains are found may have been part of the lower city.

There were several roads from Pheneus to the surrounding towns. Of these the northern road to Achaea ran through the Pheneatic plain. Upon this road, at the distance of 15 stadia from the city, was a temple of Apollo Pythius, which was in ruins in the time of Pausanias. A little above the temple the road divided, the one to the left leading across Mount Crathis to Aegeira, and the other to the right running to Pellene: the boundaries of Aegeira and Pheneus were marked by a temple of Artemis Pyronia, and those of Pellene and Pheneus by that which is called Porinas (ὁ καλούμενος Πωρ́ινας), supposed by Leake to be a river, but by Ernst Curtius a rock.[13]

Pausanias describes the two roads which led westward from Pheneus around a mountain – that to the right or northwest leading to Nonacris and the supposed river Styx, and that to the left to Cleitor.[14] Nonacris was in the territory of Pheneus. The road to Cleitor ran at first along the canal of Heracles, and then crossed the mountain, which formed the natural boundary between the Pheneatis and Cleitoria, close to the village of Lycuria. On the other side of the mountain the road passed by the sources of the river Ladon.[15] This mountain, from which the Ladon springs, was called Penteleta (Πεντελεία).[16] The fortress, named Penteleium (Πεντέλειον), which Plutarch says was near Pheneus, must have been situated upon this mountain.[17]

The southern road from Pheneus led to Orchomenus, and was the way by which Pausanias came to the former city. The road passed from the Orchomenian plain to that of Pheneus through a narrow ravine (φάραγξ); in the middle of which was a fountain of water, and at the further extremity the village of Caryae. The mountains on either side were named Oryxis (Ὄρυξις), and Sciathis (Σκίαθις), and at the foot of either was a subterraneous channel, which carried off the water from the plain.[18] The eastern road from Pheneus led to Stymphalus, across Mount Geronteium, which formed the boundary between the territories of the two cities.

To the left of Mt. Geronteium near the road was a mountain called Tricrena (Τρίκρηνα), or the three fountains; and near the latter was another mountain called Sepia (Σηπία), where Aepytus is said to have perished from the bite of a snake.[19]

Its site is located near the modern Archaia Feneos, formerly Kalyvia,[20][21] in the municipal unit of Feneos.

References

- Homer. Iliad. 2.605.

- Stephanus of Byzantium. Ethnica. s.v.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.14.3.

- Alciphr. 3.48

- So in Polybius

- Catull. 68.109.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.14.1.

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia. 31.5.30.

- Strabo. Geographica. viii. p.389. Page numbers refer to those of Isaac Casaubon's edition.

- Theophr. Hist. Plant. 3.1; Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica (Historical Library). 15.49.

- Virgil. Aeneid. 8.165.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.14.4. , et seq.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.15.5. -9.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.17.6.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.19.4. , 8.20.1.

- Hesych. and Phot. s.v.

- Plutarch, Arat. 39, Cleom. 17.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.13.6. , 8.14.1.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 8.16.1. -2.

- Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 58, and directory notes accompanying.

- Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

![]()