Penn's Creek massacre

The Penn's Creek massacre was an October 16, 1755 raid by Lenape (Delaware) Native Americans on a settlement along Penn's Creek,[n 1] a tributary of the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania. It was the first of a series of deadly raids on Pennsylvania settlements by Native Americans allied with the French in the French and Indian War.

| Penn's Creek massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the French and Indian War | |

Penn's Creek | |

| Location | Central Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 40.813649°N 76.856207°W |

| Date | October 16, 1755 |

| Target | The settlement at Penns Creek, Pennsylvania |

Attack type | Indian massacre, kidnapping |

| Deaths | 14 |

| Injured | 1 |

| Victims | Swiss and German settlers |

| Perpetrators | Lenape Native Americans |

Of the 26 settlers they found living on Penn's Creek, the Lenape killed 14 and took 11 captive (one man was wounded but managed to escape). Three of the preteen girls who were taken captive regained their freedom after years of slavery, and their stories have been popularized in several young adult novels and a film.

The Lenape had been angered by years of European settlers encroaching on their land. They had lost their traditional lands in the Lehigh Valley to the provincial government of Pennsylvania in a fraudulent deal known as the Walking Purchase, and many of them had subsequently moved into the Susquehanna Valley by permission of the Iroquois. One year before the Penn's Creek massacre, the Iroquois had sold much of the Susquehanna Valley to the governments of Pennsylvania and Connecticut without consulting the Lenape, who once again found themselves being displaced by arriving settlers.

As a direct result of the Penn's Creek massacre and subsequent raids, Pennsylvania assemblyman Benjamin Franklin persuaded the governor and assembly of the province to abandon its roots in Quaker pacifism and establish an armed military force and a chain of forts to protect the settlements. Franklin himself helped to organize and train the first Pennsylvania regiments. The Lenape and other displaced Native Americans continued their attacks on settlers and battles with the provincial forces for three years, until the Treaty of Easton was signed between the tribes and the British in 1758.

Background

Albany and Walking Purchases

One year before the massacre, delegates from seven colonies met with 150 leaders from the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy at the 1754 Albany Congress. The purpose of the gathering was to solidify the alliance between the British and the Iroquois in the face of a growing French challenge to British control of the colonies.[3] During the Albany Congress, the Iroquois sold much of the Susquehanna Valley to a delegation from the provincial government of Pennsylvania, which sought the land for the purpose of opening it up to European settlement, in a deal that became known as the Albany Purchase.[4][5] Two of the men in this Pennsylvania delegation were Benjamin Franklin and John Penn, the grandson of the province's founder, William Penn.[6] The Iroquois reserved some parts of the Susquehanna Valley, including the sub-valley called the Wyoming Valley, from the sale for the use of themselves and their allies, but only days after they signed the agreement, a delegation from Connecticut plied the Iroquois leaders with rum and induced them to sign over the Wyoming Valley while they were intoxicated.[7]

Although the provincial governments recognized the Iroquois as the sole owners of the land, the Lenape had been living in the Wyoming Valley and other parts of the Susquehanna Valley since having been forced off their own traditional lands in the Lehigh Valley of eastern Pennsylvania 17 years earlier by the 1737 Walking Purchase. In that event, John Penn's uncles (Thomas Penn and John "The American" Penn) had produced a copy of what was likely an unsigned draft of a deed which had been drawn up 50 years earlier, when their father William Penn had been considering buying land from the Lenape; it stated that the Lenape had sold William Penn as much land in their valley as could be walked by a man in a day-and-a-half.[8] Although the Lenape protested the validity of the document, they were told by the provincial government that it was legally binding. Believing they had no choice, four Lenape chiefs signed an agreement to abide by the terms of the deed after their more powerful allies the Iroquois, whose protection the Lenape were under by an agreement between the two tribes wherein the Iroquois were the "men" and the Lenape the "women" in their relationship,[n 2] refused to intervene on their behalf.[10] The Penn brothers then hired the three fastest runners in the colony to take the "walk" and had paths secretly cleared and marked ahead of them. Two of the three runners gave up well before the allotted time ran out, but one, Edward Marshall, managed to cover about 65 miles in 18 hours, resulting in all of the Lenape's land being taken from them.[8]

In a 1743 communication to the governor of Pennsylvania, the Iroquois confederation overseer, Oneida chief Shikellamy, had complained about white settlers encroaching into the Susquehanna Valley. In that message, Shikellamy stated that the Iroquois had granted the land surrounding a Susquehanna tributary, the Juniata River, "to our cousins the Delawares (Lenape) and our brethren the Shawanese (Shawnee) for a hunting-ground, and we ourselves hunt there sometimes."[11] Nevertheless, the Iroquois did not consult the Lenape or the Shawnee before selling the land eleven years later to Pennsylvania and Connecticut.[7]

Thus the Lenape found their current home sold for European settlement. This resulted in a rift between the Lenape and the Iroquois and caused Lenape resentment toward the German and Swiss settlers who immediately began moving into the Valley.[12]

French and Indian War

One year after the Albany Purchase, the French and Indian War between Great Britain and France began, with each side seeking control of the North American colonies. Although the Iroquois refused to take sides for the first four years of the conflict and instructed all of the tribes under their protection to do the same,[13] the Lenape and the Shawnee broke ranks and joined northern tribes the Huron, Ottawa and Ojibwe in forging an alliance with the French.[14]

On July 9, 1755, the French and their Native American allies decisively defeated a combined force of colonial and British soldiers led by General Edward Braddock at the Battle of the Monongahela in Braddock's Field, Pennsylvania, 10 miles (16 km) east of Pittsburgh.[15] Three months later, a French and Native American army of about 1,500 men prepared to march east in order to secure the Susquehanna River as a supply line. They sent ahead of them several advance parties of Lenape. It was one of these Lenape advance parties which came upon the settlement at Penn's Creek, located on the west branch of the Susquehanna River, in the early morning hours of October 16, 1755.[16]

The massacre

Before dawn on October 16, a group of eight Lenape warriors attacked the settlement of Penn's Creek. The warriors' names were Kech Kinnyperlin, Joseph Compass and young Joseph Compass, young Thomas Hickman, Kalasquay,[n 3] Souchy, Machynego and Katoochquay.[18]

After firing several shots, the Lenape first attacked the Swiss farmer Jean Jacques Le Roy[n 4] before setting his house on fire. His body was later found partially burned with two tomahawks still buried in his forehead.[20] A spring that emerges from the ground near the site where his body was discovered is today known as Le Roy's Spring, and the tiny stream that flows from it into Penn's Creek is known as Sweitzer's (Swisser's) Run.[15]

Le Roy's son, also named Jean Jacques and called Jacob, fought with his father's killers but was overpowered and taken captive, along with his 12-year-old sister Marie and another young girl who was living in the house[20] (Mary Ann Villars). When a neighbor of Le Roy's by the name of Bastian rode up on horseback, he was shot and then scalped.[15][21]

Two of the Lenape then traveled to the Leininger household, approximately a half-mile away. There, they demanded rum, but none was in the house so they were given tobacco instead. After they smoked a pipe, they stated "We are Allegheny Indians, and your enemies. You must all die!". They shot Sebastian Leininger and tomahawked his 20-year-old son before taking his daughters, 12-year-old Barbara and 9-year-old Regina, captive.[22] Mrs. Leininger and another son were away at a mill and were thus spared.[23]

Several of the Lenape took the prisoners (as well as horses and provisions they had plundered) from the Le Roy and Leininger households into the forest where they were joined by the rest of the Lenape warriors, who brought with them six scalps and stated that they had had a good hunt that day.[24] Later, some of the Lenape went back into the settlement and resumed killing, returning in the evening with nine more scalps and five more prisoners: Hanna Breilinger's husband, Jacob, had been killed and she and her two children taken captive.[25] A settler named Peter Lick was also taken along with his two sons, John and William.[23]

Of the fourteen settlers murdered at Penn's Creek, thirteen were men and elderly women, and one was a two-week-old infant. One unidentified man was wounded but escaped and made his way to a nearby settlement to report what had happened.[26]

Aftermath

John Harris expedition

As news of the massacre spread, panic gripped the settlements.[27] Trading post owner John Harris Jr. wrote to the governor and offered to lead an expedition upriver to try to pacify the Native Americans and find out the mindset of those at Shamokin (now called Sunbury), since the Indians there were known to be friendly to settlers. He gathered a group of 40 or 50 men and set out on October 22.[15][26][28]

At Shamokin, they found a gathering of Lenape painted all in black who had come from the Ohio and Allegheny River Valleys. Andrew Montour, an Indian of mixed Oneida, Algonquin and French ancestry, was among those painted in black but was known to Harris and often acted as an interpreter. He advised Harris to return home immediately by way of the east side of the Susquehanna.[29]

Harris turned his group back but disregarded Montour's warning to stay on the east side of the river. As the group headed back along the west side of the Susquehanna on October 25, they were ambushed by twenty or thirty Lenape in what is now the northern end of the borough of Selinsgrove.[26] Harris later reported that he and his men killed four of the attackers while losing three of their own number, and that "four or five" more of his group drowned in the river while attempting to escape.[29] A doctor who was riding behind Harris on the same horse was shot in the back and killed. Harris's horse was then shot out from under him and he had to swim across the river to safety.[26]

On either that same day or the next, the Lenape crossed the Susquehanna and attacked settlements at Hunter's Mill. Upon learning of the ambush and subsequent attacks, the Seneca chief Belt of Wampum[n 5] gathered thirty of his own men and set out in pursuit of the perpetrators, although it's not known if they met with any success.[29]

Further attacks

Penn's Creek was the first of a series of attacks on Pennsylvania settlements by the Lenape and other tribes allied with the French. Two weeks after the massacre, Lenape and Shawnee together were led by the Lenape war chief Shingas (also known as The Delaware King and called Shingas the Terrible by colonists) in nearly wiping out the Scotch-Irish settlements in what is now Fulton and Franklin counties on the Maryland border, in what became known as the Great Cove Massacre. They killed or took captive 47 out of 93 settlers in the Big Cove settlement alone in a brutal incursion that lasted several days and saw children murdered in front of their parents and wives forced to watch their husbands tortured; one woman over ninety years old was later found impaled on a stake with both breasts cut off.[31][32] Next, the Lenape attacked settlers along Swatara Creek in what is now Lebanon County and Tulpehocken Creek in Berks County.[33]

In late November, a dozen Lenape led by the chief Captain Jacobs invaded Gnadenhuetten (now Lehighton), a farming community for Christian Indians run by Moravian settlers. Eleven settlers were either murdered or taken captive.[32] From December 10 to 11, a half-dozen Lenape killed or kidnapped members of five farming families along the Pohopoco Creek in what is now Towamensing Township.[32]

They continued on to the area that is today Stroudsburg and on December 11, 1755, besieged the plantation of the Brodhead family. The five Brodhead brothers (Charles, Daniel, Garett, John and Luke) and their youngest sister, 12-year-old Ann, barricaded themselves inside along with some local settlers who had sought refuge at their home and fought an hours-long gun battle that ultimately held off the attackers.[34] It was the first of several attacks in the coming years on the Brodhead home, and the family was widely commended for their bravery in battling the threat.[35]

There were only about 200 warriors among the Susquehanna Lenape, but their numbers were soon bolstered by approximately 700 Ohio Lenape who came east to join them in their raids. By March 1756, five months after beginning their killing spree at Penn's Creek, they had killed some 200 settlers and taken an equal number captive.[36] Settlers across eastern Pennsylvania abandoned their homesteads and fled to more-populated areas to the south and east, in hopes of finding safety in numbers.[32]

Pennsylvania's response

Pennsylvania had been founded by Quakers, and that religion's core doctrine of pacifism meant that the province's Assembly had always refused to establish a permanent military force. As the settlements were decimated, Governor Robert Hunter Morris and the Assembly argued over whether or not proprietary estates should be taxed to raise money to defend them. In desperation, hundreds of Berks County German settlers marched on Philadelphia on November 25, 1755[37] carrying with them the scalped and mutilated bodies of some of their murdered neighbors. They dragged the bodies through the streets with placards attached declaring that these were the victims of the Quaker policy of non-resistance. They then surrounded the House of Assembly and placed the rotting corpses in its doorways.[38]

Benjamin Franklin sat on the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1755. Gauging the panic that was spreading throughout the province, he had strongly urged Governor Morris and his fellow assemblymen that military force was necessary in the face of the Native American threat.[32] On November 25, the same day the settlers' corpses were left on their doorstep, the Assembly acquiesced to Franklin's proposal for an unpaid volunteer force and passed Pennsylvania's first Militia Act. Two days later, a defense fund was created by a compromise hammered out by Franklin and fellow Assemblyman Joseph Galloway; it allowed for the taxing of colonists but exempted William Penn's sons and their land in exchange for a contribution from them.[32] By early 1756, construction was underway on a chain of frontier forts, including Fort Augusta in the northern Susquehanna Valley, that ran along the Blue Mountains from the Delaware River to the Maryland line.[39]

In mid-December 1755, two months after the Penn's Creek massacre, Franklin himself set out to help the colonists prepare for battle. He visited towns like Bethlehem and Easton, now crowded with settlers who had fled their land, and signed up volunteers. Franklin appointed sentries and organized armed patrols and defenses.[32]

On New Year's Day 1756, twenty new militiamen who were building a fort on the site of the Gnadenhuetten massacre were lured into an ambush and killed by Indians who had come through the Lehigh Gap. Stunned at this breach, Governor Morris granted Franklin blanket authority to appoint and dismiss military officers and distribute weapons in Northampton County. By February, Pennsylvania had 919 paid colonial troops, with 389 in Northampton County alone.[32] Later that year, a law was passed that subjected the commonwealth's troops to military discipline, and in 1757, the last vestiges of pacifism fell as military service was made compulsory for men in Pennsylvania.[32]

Still, they could not stop the Lenape and their Native American allies from continuing the raids. Nor could the Iroquois Confederacy, which ostensibly had authority over all of the Native American tribes in the region and which had thus far remained neutral in the war. The Lenape, still angry over the sale of the Susquehanna Valley in the Albany Purchase, were further angered when the Iroquois noted their lesser status by reminding them that they were the "women" in the relationship between their two tribes during a contentious March 1756 conference of all the Susquehanna Indian leaders. An eastern Lenape spokesman spat back:

We are Men and are determined not to be ruled any longer by you as Women. We are determined to cut off all the English except those that may make their escape from us in ships; so say no more to us on that head, lest we cut off your private parts, and make Women of you, as you have done of us.[40]

In April 1756, Pennsylvania declared that it would pay a bounty of $130 for the scalp of every Lenape male over ten years of age and $50 for a Lenape woman's scalp, or $150 for a male Lenape prisoner and $130 for a female one.[41] New Jersey soon followed suit. Pennsylvania assemblyman James Hamilton justified the bounties as “the only way to clear our frontiers of … savages & … infinitely cheapest in the end."[42][43] There were fears that this would encourage indiscriminate killing of innocent Native Americans by those seeking payment, but as only eight scalp bounties were paid out by Pennsylvania during the entire colonial period, it appears that few were either willing or able to pursue such rewards.[44]

Pennsylvania suffered a crushing defeat when Lenape war chief Captain Jacobs and 100 warriors burned down the newly-constructed Fort Granville, considered one of the strongest-built forts in all of the Americas, on July 31, 1756. After first drawing away much of the fort's garrison by attacking settlers in the region, the Lenape, along with 55 French soldiers, either killed or captured all of the 24 men who had been left to defend the fort, as well as a number of civilians who were being sheltered inside. In response, the province's militia went on the offensive for the first time with the Kittanning Expedition: On September 8, 1756, a Pennsylvania regiment led by Colonel John Armstrong raided the Lenape stronghold village of Kittaning (where unknowingly, some of the Penn's Creek massacre captives were being held), burning it to the ground[45] and killing Captain Jacobs along with 50 other Indians.[32] Only seven of the approximately 100 captives who were held there were liberated, however, and the ones from Penn's Creek were not among them.[45]

Treaty of Easton

Teedyuscung, a Lenape who had led some of the raids on settlements, around this time emerged as the leader of displaced Native Americans who had taken up residence in the Wyoming Valley, a section of the Susquehanna Valley located in northeastern Pennsylvania. Teedyuscung asserted that he represented ten Native American tribes, including the Iroquois, and on their behalf, he entered into treaty negotiations with Pennsylvania authorities at a series of conferences in Easton that began in 1756. His main objective was to secure the Wyoming Valley for the Lenape, and he gave speeches denouncing as fraudulent the land deals made by the Penn family which had taken away Native American lands. He was aided and encouraged by Quakers sympathetic to the Indians' plight, but faced resistance from both the Penn family and the Iroquois, who claimed authority over all Native American lands in Pennsylvania and had not in fact appointed Teedyuscung as their representative.[43]

Although often a powerful speaker, Teedyuscung's chronic alcohol use also led to quarrelsome, drunken outbursts and occasional bouts of tears that made him a less-than-reliable leader and exasperated his colonial allies;[46] he was eventually outmaneuvered by the British colonial government's representative Conrad Weiser and the Iroquois and failed to obtain the rights to the Wyoming Valley for his people.[47]

Nonetheless, the talks he had begun resulted in the October 1758 Treaty of Easton, which ended Pennsylvania's war with the Indians and brought about an uneasy peace by restoring some of the disputed territory acquired by the province (including three-quarters of the Susquehanna Valley land bought in the Albany Purchase)[48] to the Native American tribes and by promising that the British would not establish settlements in the Ohio Country region west of the Allegheny Mountains once the French had been defeated.[43] In return, the Native Americans (who had just been badly defeated by the British at the Battle of Fort Ligonier and saw that the war had turned against the French) agreed to cease fighting for the French in the current war and end the raids on settlements.[47]

The captives

The ultimate fates of Peter Lick and his two sons, Hanna Breilinger and one of her two children, and Mary Ann Villars have been lost to history. It is known that Jacob Le Roy survived captivity because his name appears on a later deed in which he sold Le Roy family property, but there is no record of how or when he came to be freed.[49]

Marie Le Roy and Barbara Leininger

The Lenape who had not traveled east after the massacre next took their prisoners and headed west. Twelve-year-old girls Marie Le Roy and Barbara Leininger were given as property to the Lenape warrior named Kalasquay.[50] Barbara attempted to escape but was almost immediately recaptured and condemned to be burned to death. She was given a Bible and a fire was built, but just as she was about to be thrown into the flames, a young Lenape begged so earnestly for her life that she was spared on condition that she promise not to run away again and that she stop crying.[51]

The Lenape took their prisoners through forests and swamps, avoiding roads where they might be discovered. The captives were forced to walk barefoot over rocks and stumps until their feet were worn down to the bone and tendon and they were in agony. Their clothing, caught on brambles and branches, shredded and fell off. Older children were made to carry smaller ones bound to their backs.[52] Marie Le Roy was separated from her brother Jacob when the group split up at the village of Chinklacamoose in their second week of traveling[51] and Barbara Leininger was separated from her sister, Regina, at some unknown point approximately 400 miles from Penn's Creek.[53]

Marie and Barbara were in a group that arrived in Kittaning (then also known as Kittany) in December and included fellow Penn's Creek captive Hanna Breilinger and her two children. They remained there for nine months, until September 1756. They were put to work tanning leather, clearing land and building huts, planting corn and making moccasins.[54] There was little food and at times the prisoners had to subsist on nothing but acorns, roots, grass and bark.[55] One of Hanna Breilinger's children starved to death at Kittaning.[15] In September 1756, the prisoners were taken deep into the forest when provincial troops arrived to attack the village during the Kittaning Expedition, and warned not to attempt escape. When the attack was over, they were brought back and found Kittaning had been burned to the ground.[56] An Englishwoman who was also being held captive by the Lenape had attempted to escape with the provincial forces but had been recaptured and was sentenced to death. Le Roy and Leininger later recounted:

Having been recaptured by the savages, and brought back to Kittanny, she was put to death in an unheard of way. First, they scalped her; next, they laid burning splinters of wood, here and there, upon her body, and then they cut off her ears and fingers, forcing them into her mouth so that she had to swallow them. Amidst such torments, this woman lived from nine o'clock in the morning until toward sunset, when a French officer took compassion on her, and put her out of her misery. An English soldier, on the contrary, named John, who escaped from prison at Lancaster and joined the French, had a piece of flesh cut from her body, and ate it. When she was dead, the Indians chopped her in two, through the middle, and let her lie until the dogs came and devoured her[57]

Three days later, an Englishman who had escaped was also recaptured and tortured to death. Le Roy and Leininger would recount that "his torments, however, continued only about three hours; but his screams were frightful to listen to." Due to hard rain, the Lenape could not keep the fire they had lain him in going, so they used him as a shooting target without killing him. When he screamed for a drink of water, they poured melted lead down his throat, which killed him instantly.[58] Le Roy and Leininger:

It is easy to imagine what an impression such fearful instances of cruelty make upon the mind of a poor captive. Does he attempt to escape from the savages, he knows in advance that, if retaken, he will be roasted alive. Hence he must compare two evils, namely, either to remain among them a prisoner forever, or to die a cruel death. Is he fully resolved to endure the latter, then he may run away with a brave heart.[58]

The girls were next taken to Fort Duquesne in Pittsburgh, where they were put to work for the French soldiers while their Lenape masters took their wages. Although they were better fed in the fort than they had been in Kittaning and the French soldiers tried to induce them to stay with them, the girls reasoned that the Native Americans were more likely to make peace with the English than the French were, and that they would have more chances for escape in the forest than in a fort, so they refused.[59] They were moved to several other villages in western Pennsylvania by their captors over the next two years.[60]

Three years after the Penn's Creek massacre, in October 1758, the French and Indian army was badly defeated by the English in the Battle of Fort Ligonier. This caused a panic among the Native Americans of western Pennsylvania, who decided to sign the Treaty of Easton and abandon the war. They burned their crops and villages before fleeing 150 miles farther west to the village of Moschkingo in Ohio. Forced to go along, the now 15-year-old Marie Le Roy and Barbara Leininger met a young English captive there named David Breckenridge. They made a plan to escape with him and another young Englishman, Owen Gibson. On March 16, 1759, while most of the Lenape men were away selling pelts, the four young people fled east on foot.[61]

They endured a series of hardships on their 250-mile journey to Fort Pitt in Pittsburgh[n 6] They traveled over one hundred miles in the first four days to reach the Ohio River. Leininger nearly drowned crossing Little Beaver Creek, Owen Gibson was wounded by a bear he had shot, they ran out of provisions and Gibson lost his flint and steel, leaving them to spend the last four nights of their journey sleeping in the snow with no fire.[63] Nonetheless, all four made it to Fort Pitt and safety on the last night of March.[64] A month later, Le Roy and Leininger were taken to Philadelphia.[65] They related the story of their captivity later that year in a published pamphlet titled The Narrative of Marie le Roy and Barbara Leininger, for Three Years Captives Among the Indians.[66]

At the end of this narrative, Barbara and Marie listed the names, place of capture and last known locations of over 50 other captives they had met during their time with the Lenape, in order that their relatives might know they were still alive and have hope of seeing them again. They stated that they had also met many other captives whose names they either did not know or could not recall.[67]

Regina Leininger

Nine-year-old Regina Leininger was separated from her sister Barbara early in their captivity and given as a slave to an old Lenape woman, along with a two-year-old girl who had been captured from another settlement. The two girls were treated very harshly by their mistress, who often beat them and drove them into the woods to find roots and berries to feed themselves whenever her son, who supplied them with food when he was present, was away. They lived with the woman for nine years. An account of the end of Regina's captivity was told by the Reverend Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, patriarch of the Lutheran church in the United States, in his Hallische Nachrichten.[68]

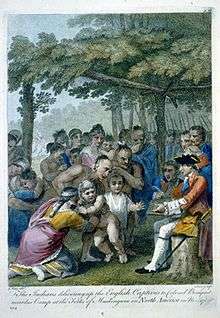

After the French and Indian War ended in 1763 with British victory, the Lenape were among a number of Native American tribes who were dissatisfied with British postwar policies and with settlers continuing to move into the Ohio Country in violation of the Treaty of Easton. They took part in Pontiac's War from 1763 until 1764 in an effort to drive the British from the Great Lakes region, Ohio and Illinois. The effort failed and under peace negotiations with British Colonel Henry Bouquet, the Native Americans were obligated to surrender all of the captives in their possession. Approximately 200 captives were rounded up and brought to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and word was sent out around the colonies for those who might have family members among them to come.[68]

Regina Leininger was by this time eighteen years old. According to Muhlenberg, her mother arrived in Carlisle on December 31, 1764[53] in hopes of finding Regina there, but after searching the line of captives, she was unable to recognize her daughter among them and was in tears. Colonel Bouquet suggested that she try doing something that would recall the past to her children, and Mrs. Leininger began to recite a German hymn that she had sung to her children when they were small, "Allein, und doch nicht ganz allein". In English, the opening lines are "Alone yet not alone am I, though in this solitude so drear, I feel my Savior always nigh". With those words, a young woman began to sing along and threw her arms around Mrs. Leininger. Regina had forgotten how to speak German, but she still remembered the hymn.[69]

Muhlenberg's narrative states that the younger girl who had been held captive with Regina was now eleven and refused to be separated from her. As she likely had no family left, Mrs. Leininger took her in as well and the three departed together.[69]

Reverend Muhlenberg neglected to give the family name of mother and daughter in his accounting of the story, and as a result, the captive girl was for many years misidentified as another kidnapped settler, Regina Hartmann. A 1905 investigation by the Historical Society of Berks County, however, definitively revealed her to be Regina Leininger: the description of her having been captured on October 16, 1755 along with her sister, Barbara, after their father and brother were killed and while their mother and another brother were absent could only have fit Leininger.[70]

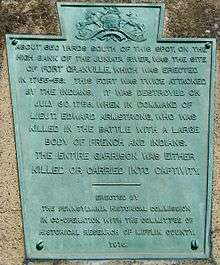

Memorials

The Pennsylvania Historical Commission and the Snyder County Historical Society jointly erected a memorial dedicated to the Penn's Creek massacre in October 1915, on the 160th anniversary of the massacre itself. The memorial is located alongside Penn's Creek north of Selinsgrove, near the site where John Harris' group was ambushed,[71] and takes the form of a large piece of granite with two plaques. The upper plaque commemorates the massacre and the lower plaque on the granite block commemorates Harris' ill-fated expedition,[26] reading

On October 25, 1755, John Harris, founder of Harrisburg, and a party of 40 men who came up the river to investigate the John Penn's Creek massacre were ambushed by a party of Indians near the mouth of this creek at the head of the Isle of Que about one third of a mile south of this spot.[72]

There is also another stone block with a plaque at the site of the Le Roy house, where the massacre began. This one was put up by the Historical Commission in 1919 and reads

John Jacob LeRoy was killed by the Indians near this spot during the time of the Penns Creek Massacre, October 16, 1755. This was the first act of hostility by the Indians of this province following the defeat of General Edward Braddock, July 9, 1755. A daughter of John Jacob LeRoy, Marie, and Barbara Leininger were taken captive at this time and taken to Muskingum in Ohio, from which they escaped several years later and returned to Philadelphia[73]

In popular culture

The stories of the three captive Penn's Creek girls who eventually found freedom again have been fictionalized in three young adult novels and a film:

Books

- Craven, Tracy Leininger. Alone Yet Not Alone: The Story of Barbara and Regina Leininger (2003) Account of the capture and eventual reunion of the Leininger sisters, written with a strong focus on Christian faith. The author is a distant relative of Barbara and Regina Leininger.[74]

- Keehn, Sally M. I am Regina (1991) Based upon the nine-year captivity of Regina Leininger.[75]

- Loder, Michael Wescott. Taken Beyond the Ohio (2019) This one is focused upon Barbara Leininger and Marie LeRoy.[76]

Film

Alone Yet Not Alone (Enthuse Entertainment, 2013; directed by Ray Bengston and George D.Escobar: Screenplay by Escobar and James Richards). Limited-release film based upon Tracy Leininger Craven's young adult book of the same name (above).[77]

Notes

- Sources lack consistency as to whether the name of the creek is properly spelled with or without an apostrophe (Penns or Penn's).[1][2] With the exception of direct quotes, this article uses the spelling with an apostrophe for both the creek itself and the massacre.

- The agreement which symbolically emasculated the Lenape and made them the "women" to the Iroquois' "men" is believed to have been the result of the Iroquois having defeated the Lenape in warfare some time before 1712. Under this agreement, the Lenape were forbidden to make war or peace treaties or to sell their own land without the permission of the Iroquois.[9]

- .'Kalasquay' is alternatively spelled 'Galasko' in some sources.[17]

- Jean Jacques Le Roy is called John Jacob Le Roy and John Jacob King in various sources.[19]

- Belt of Wampum was also known by the names The Old Belt and White Thunder.[30]

- Fort Pitt had been built on the site of Fort Duquesne, where Marie Le Roy and Barbara Leininger had been made to work for the French soldiers several years earlier. The French had burned down Fort Duquesne the previous Fall before abandoning the site to British forces. [62]

References

- Snyder, Downie & Kalp 2000, p. 6

- Denaci 2007, p. 307

- Morris 1956

- Weslager 1972, p. 215

- Trask 1960, p. 283.

- Trask 1960, p. 276

- Weslager 1972, p. 216.

- Hunter & Waddell 2006, p. 3.

- Weslager 1944

- Weslager 1972, pp. 188–191.

- Linn 1883, p. 1.

- Weslager 1972, pp. 218–219.

- Johnson 2003, p. 14.

- Weslager 1972, p. 224.

- Deans 1963.

- Linn 1883, p. 2.

- Denaci 2007, p. 312

- Linn 1877, p. 11.

- Linn 1877, p. 10

- Denaci 2007, p. 307.

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, pp. 407–408

- Denaci 2007, pp. 307-308

- Snyder, Downie & Kalp 2000, p. 10.

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, p. 408

- Early 1905, p. 135.

- Penn's Creek Massacre of 1755 2013

- Wagenseller 1915, p. 31.

- Sipe 1929, p. 209

- Sipe 1929, p. 210

- Sipe 1929, p. 209

- Sipe 1929, p. 217

- Venditta 2006

- Snyder, Downie & Kalp 2000, p. 9.

- Leiser 2011

- Sipe 1929, p. 244

- Wallace 1945, p. 87

- Silver 2007, p. 78

- Sipe 1929, pp. 251–252

- Sipe 1929, p. 252

- Wallace 1945, pp. 91–92

- Wallace 1945, p. 93

- Silver 2007, p. 161

- Shannon 2015

- Silver 2007, p. 162

- Denaci 2007, pp. 316-317

- Wallace 1945, pp. 131–136

- Kummerow 2008.

- Waddell 2005, p. 229

- Snyder, Downie & Kalp 2000, p. 12

- Denaci 2007, p. 312

- Denaci 2007, p. 313

- Early 1905, pp. 130–131

- Early 1905, p. 131

- Denaci 2007, p. 316

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, pp. 409–410

- Denaci 2007, p. 317

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, p. 410

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, p. 411

- Denaci 2007, p. 319

- Denaci 2007, p. 320

- Denaci 2007, p. 322

- Withers 1895, p. 73

- Denaci 2007, p. 325

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, p. 416

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, p. 417

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759

- Le Roy & Leininger 1759, pp. 417–419

- Sipe 1929, p. 214

- Sipe 1929, p. 215

- Early 1905, pp. 132–139

- Ferree 1916, p. 207

- Rabinowitz 2016, p. 92

- Ferree 1920, p. 160

- Alone Yet Not Alone 2012

- I am Regina 1991

- By the Book 2018

- Bond 2014.

Sources

- "Alone Yet Not Alone". Publishers Weekly. 259 (51). December 17, 2012. ISSN 0000-0019. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- Bond, Paul (April 7, 2014). "Controversial 'Alone Yet Not Alone' to Be Released in 200 Theaters". Hollywood Reporter.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "By the Book". Susquehanna Life. Fall 2018. September 10, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- Deans, John B (1963). "The Penn's Creek Massacre" (PDF). Union County Sesquicentennial: The Story of a County, 1813-1963. Lewisburg, PA: Focht Printing Co. OCLC 1011283847.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Denaci, Ruth Ann (Summer 2007). "The Penn's Creek Massacre and the Captivity of Marie Le Roy and Barbara Leininger". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 74 (3): 307–332. JSTOR 27778784.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Early, Rev. J.W. (1905). "Indian Massacres in Berks County". Transactions of the Historical Society of Berks County: Embracing Papers Read to the Society, Vol. II. Reading, PA: B.F. Owens. OCLC 65212356.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferree, Barr (1916). "The Patriotic Year in Pennsylvania, 1915: Union County". Yearbook of the Pennsylvania Society (16). OCLC 476082813. Retrieved December 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferree, Barr (1920). "The Patriotic Year in Pennsylvania, 1919: Union County". Yearbook of the Pennsylvania Society (20). OCLC 476082813. Retrieved December 5, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunter, William A.; Waddell, Louis (2006). The Walking Purchase. Harrisburg, PA: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "I am Regina". Publishers Weekly. 238 (19). April 29, 1991. ISSN 0000-0019. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- Johnson, Michael (2003). Tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy. Osprey. ISBN 978-1841764900.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kummerow, Burton (October 19, 2008). "Treaty of Easton Gives Sides New Hope of Peace". PittsburghTribune-Review. Tribune-Review Publishing Company. OCLC 777492024.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leiser, Amy (November 11, 2011). "Stroudsburg and East Stroudsburg Founded in the 1730s". Monroe County Historical Association. Retrieved August 24, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Roy, Marie; Leininger, Barbara (1759). The Narrative of Marie le Roy and Barbara Leininger, for Three Years Captives Among the Indians. Translated by Rev. Edmund de Schweinitz – via The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography volume 29, 1905.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Linn, John Blair (1877). Annals of Buffalo Valley, Pennsylvania, 1755-1855. Harrisburg, PA: Lane S. Hart.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Linn, John Blair (1883). History of Centre and Clinton Counties, Pennsylvania. J.B. Lippincott & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morris, Richard B. (February 1956). "Benjamin Franklin's Grand Design". American Heritage. 7 (2). OCLC 270698795.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Penn's Creek Massacre of 1755". Snyder County Post. 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- Rabinowitz, Richard. (2016). Curating America: Journeys through Storyscapes of the American Past. Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina University Press. ISBN 978-1469629506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shannon, Timothy J. (2015). "Native American-Pennsylvania Relations, 1754-89". The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. OCLC 1049779577.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silver, Peter R. (2007). Our Savage Neighbors: How Indian War Transformed Early America. New York: WW Norton. ISBN 978-0393062489.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sipe, C. Hale (1929). The Indian wars of Pennsylvania: An account of the Indian events, in Pennsylvania, of the French and Indian War, Pontiac's War, Lord Dunmore's War, the Revolutionary War and the Indian Uprising from 1789 to 1795. Tragedies of the Pennsylvania frontier. Telegraph Press. ISBN 978-5871748480.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snyder, Charles M.; Downie, John W.; Kalp, Lois (2000). Union County, Pennsylvania: A Celebration of History. Lewisburg, PA: Union County Historical Society. ISBN 978-0917127137.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trask, Roger R. (July 1960). "Pennsylvania and the Albany Congress, 1754". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 27 (3): 273–290. JSTOR 27769967.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Venditta, David (November 26, 2006). "We Are Now the Frontier". The Morning Call. Tribune Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waddell, Louis (Spring 2005). "Thomas and Richard Penn Return Albany Purchase Land to the Six Nations: The Power of Attorney of November 7, 1757". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 72 (2): 229–240. JSTOR 27778666.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wagenseller, John F. (Chairman of the Book Committee) (1915). Souvenir Book of Selingsgrove, Pennsylvania. Harrisburg, PA: Telegraph Printing Company. pp. 17–19.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace, Anthony F.C. (1945). King of the Delawares: Teedyuscung, 1700-1763. Syracuse: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0815624981.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weslager, C.A. (December 15, 1944). "The Delaware Indians as women". Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 34 (12): 381–388. JSTOR 24531500.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weslager, Clinton A. (1972). The Delaware Indians: A History. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813507026.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Withers, Alexander.Scott (1895). Chronicles of Border Warfare. Cincinnati: Stewart & Kidd Company. OCLC 478032092.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Slavishak, Edward (2015). "Three Miles, Two Creeks: Local Pennsylvania History in the Classroom". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 82 (1): 22. doi:10.5325/pennhistory.82.1.0022.