Pauropoda

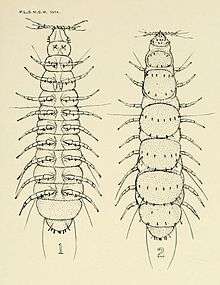

Pauropods are small, pale, millipede-like arthropods. Around 830 species in twelve families[2] are found worldwide, living in soil and leaf mould. They look rather like centipedes, but are probably the sister group to millipedes.[3]

| Pauropoda | |

|---|---|

_crop.jpg) | |

| A eurypauropod from New Zealand | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Myriapoda |

| Class: | Pauropoda |

| Orders | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Anatomy and ecology

Pauropods are soft, cylindrical animals with bodies 0.5 to 2 millimetres (0.02 to 0.08 in) long.[3] The first instar has three pairs of legs, but that number increases with each moult so that adult species may have nine to eleven pairs of legs. They have neither eyes nor hearts, although they do have sensory organs which can detect light. The body segments have ventral tracheal/spiracular pouches forming apodemes similar to those in millipedes and Symphyla, although the trachea usually connected to these structures are absent in most species. There are long sensory hairs located throughout the body segments. Pauropods can usually be identified because of their distinctive anal plate, which is unique to pauropods. Different species of pauropods can be identified based on the size and shape of their anal plate. The antennae are branching, biramous, and segmented, which is distinctive for the group.[4] Pauropods are usually either white or brown.[5]

Pauropods live in the soil, usually at densities of less than 100 per square metre (9/sq ft).[4]

Evolution and systematics

Though no fossil pauropods have been found from before the time of the Baltic amber (40 to 35 million years ago), they seem to be an old group closely related to the millipedes (Diplopoda). Their head capsules show great similarities to millipedes: both have three pairs of mouthparts and the genital openings occur in the anterior part of the body. Moreover, both groups have a pupoid phase at the end of the embryonic development. The two groups probably have a common origin.

There are two orders: Hexamerocerata and Tetramerocerata; Hexamerocerata has a purely tropical range, while in Tetramerocerata most genera are subcosmopolitan.[6] Hexamerocerata has a 6-segmented and strongly telescopic antennal stalk and a 12-segmented trunk with 12 tergites and 11 pairs of legs. The representatives are white and proportionately long and large. The one family in this order, Millotauropodidae, has one genus and a few species.[6] Tetramerocerata has a 4-segmented and scarcely telescopic antennal stalk, 6 tergites, and 8–10 pairs of legs. Representatives of this order are often small (sometimes very small), and white or brownish. Most species have nine pairs of legs as adults.[6] The four families include Pauropodidae, Afrauropodidae, Brachypauropodidae, and Eurypauropodidae. Most genera and species belong to the family Pauropodidae.

Behavior, reproduction, and diet

Pauropods are shy of light, and will attempt to distance themselves from light sources.[7] Pauropods occasionally migrate upwards or downwards throughout the soil based on moisture levels. Male pauropods place small packets of sperm on the ground, which the females use to impregnate themselves with. Pauropods have been known to eat mold, fungal hyphae, and the root hairs of plants.[5]

References

- Scheller, Ulf (2008). "A reclassification of the Pauropoda (Myriapoda)". International Journal of Myriapodology. 1 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1163/187525408X316730.

- Minelli, Alessandro (2011). "Class Chilopoda, Class Symphyla and Class Pauropoda. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148: 157–158. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.31.

- Cedric Gillott (2005). Entomology (3rd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-3182-3.

- David C. Coleman, D. A. Crossley, Jr. & Paul F. Hendrix (2004). Fundamentals of Soil Ecology (2nd ed.). Academic Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-12-179726-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Subclass Pauropoda". what-when-how.com. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- Peter Ax (2000). "Pauropoda". Multicellular Animals: The phylogenetic system of the Metazoa. Volume 2 of Multicellular Animals: A New Approach to the Phylogenetic Order in Nature. Springer. pp. 231–233. ISBN 978-3-540-67406-1.

- Minelli, Alessandro (2011). The Myriapoda - Treatise on Zoology - Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology. Brill Publishers. p. 495. ISBN 978-90-04-15611-1.

Further reading

- Ulf Scheller (1990). "Pauropoda". In Daniel L. Dindal (ed.). Soil Biology Guide. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 861–890. ISBN 978-0-471-04551-9.

- Ulf Scheller (2002). "Pauropoda". In Jorge Llorente Bousquets; Juan J. Morrone (eds.). Biodiversidad, Taxonomía y Biogeografía de Artrópodos de México: Hacia una Síntesis su Conocimiento (in Spanish). III. Tlalpan, Mexico: CONABIO.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Pauropoda |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pauropoda. |