Patent ductus arteriosus

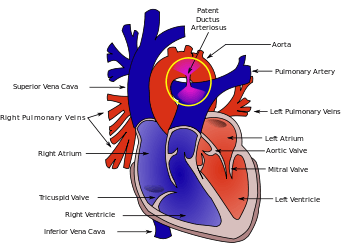

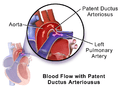

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a medical condition in which the ductus arteriosus fails to close after birth: this allows a portion of oxygenated blood from the left heart to flow back to the lungs by flowing from the aorta, which has a higher pressure, to the pulmonary artery. Symptoms are uncommon at birth and shortly thereafter, but later in the first year of life there is often the onset of an increased work of breathing and failure to gain weight at a normal rate. With time, an uncorrected PDA usually leads to pulmonary hypertension followed by right-sided heart failure.

| Patent ductus arteriosus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Persistent ductus arteriosus |

| |

| Diagram of a cross-section through a heart with PDA | |

| Specialty | Cardiac surgery, paediatrics |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, failure to thrive, tachycardia, heart murmur |

| Complications | Heart failure, Eisenmenger's syndrome, pulmonary hypertension |

| Causes | Idiopathic |

| Risk factors | Preterm birth, congenital rubella syndrome, chromosomal abnormalities, genetic conditions |

| Diagnostic method | Echocardiography, Doppler, X-ray |

| Prevention | Screening at birth, high index of suspicion in neonates at risk |

| Treatment | NSAIDs, surgery |

The ductus arteriosus is a fetal blood vessel that normally closes soon after birth. In a PDA, the vessel does not close, but remains patent (open), resulting in an abnormal transmission of blood from the aorta to the pulmonary artery. PDA is common in newborns with persistent respiratory problems such as hypoxia, and has a high occurrence in premature newborns. Premature newborns are more likely to be hypoxic and have PDA due to underdevelopment of the heart and lungs.

If transposition of the great vessels is present in addition to a PDA, the PDA is not surgically closed since it is the only way that oxygenated blood can mix with deoxygenated blood. In these cases, prostaglandins are used to keep the PDA open, and NSAIDs are not administered until surgical correction of the two defects is completed.

Signs and symptoms

Common symptoms include:

- dyspnea (shortness of breath)

Signs include:

- tachycardia (a heart rate exceeding the normal resting rate)

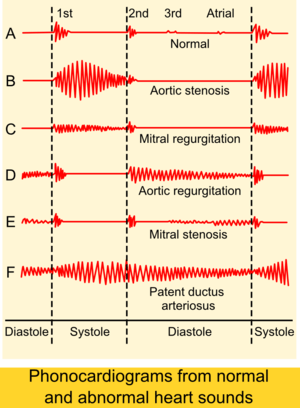

- continuous "machine-like" (also described as "rolling-thunder" and "to-and-fro") heart murmur (usually from aorta to pulmonary artery, with higher flow during systole and lower flow during diastole)

- cardiomegaly (enlarged heart, reflecting ventricular dilation and volume overload)

- left subclavicular thrill

- bounding pulse

- widened pulse pressure

- increased cardiac output

- increased systolic pressure

- poor growth[1]

- differential cyanosis, i.e. cyanosis of the lower extremities but not of the upper body.

Patients typically present in good health, with normal respirations and heart rate. If the PDA is moderate or large, widened pulse pressure and bounding peripheral pulses are frequently present, reflecting increased left ventricular stroke volume and diastolic run-off of blood into the (initially lower-resistance) pulmonary vascular bed. Prominent suprasternal and carotid pulsations may be noted secondary to increased left ventricular stroke volume.

Risk factors

Known risk factors include:

- Preterm birth

- Congenital rubella syndrome

- Chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., Down syndrome)

- Genetic conditions such as Loeys–Dietz syndrome (would also present with other heart defects), Wiedemann–Steiner syndrome, and CHARGE syndrome.

Diagnosis

PDA is usually diagnosed using noninvasive techniques. Echocardiography (in which sound waves are used to capture the motion of the heart) and associated Doppler studies are the primary methods of detecting PDA. Electrocardiography (ECG), in which electrodes are used to record the electrical activity of the heart, is not particularly helpful as no specific rhythms or ECG patterns can be used to detect PDA.[2]

A chest X-ray may be taken, which reveals overall heart size (as a reflection of the combined mass of the cardiac chambers) and the appearance of blood flow to the lungs. A small PDA most often accompanies a normal-sized heart and normal blood flow to the lungs. A large PDA generally accompanies an enlarged cardiac silhouette and increased blood flow to the lungs.

Illustration of Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Illustration of Patent Ductus Arteriosus Patent ductus arteriosus

Patent ductus arteriosus An echocardiogram of a stented persisting ductus arteriosus: One can see the aortic arch and the stent leaving. The pulmonary artery is not seen.

An echocardiogram of a stented persisting ductus arteriosus: One can see the aortic arch and the stent leaving. The pulmonary artery is not seen. An echocardiogram of a coiled persisting ductus arteriosus: One can see the aortic arch, the pulmonary artery, and the coil between them.

An echocardiogram of a coiled persisting ductus arteriosus: One can see the aortic arch, the pulmonary artery, and the coil between them.

Prevention

Some evidence suggests that indomethacin administration on the first day of life to all preterm infants reduces the risk of developing a PDA and the complications associated with PDA. Indomethacin treatment in premature infants also may reduce the need for surgical intervention.[3]

Treatment

Neonates without adverse symptoms may simply be monitored as outpatients, while symptomatic PDA can be treated with both surgical and non-surgical methods.[4] Surgically, the DA may be closed by ligation (though support in premature infants is mixed),[5] either manually tied shut, or with intravascular coils or plugs that leads to formation of a thrombus in the DA.

Devices developed by Franz Freudenthal block the blood vessel with woven structures of nitinol wire.[6]

Because prostaglandin E2 is responsible for keeping the DA open, NSAIDs (which can inhibit prostaglandin synthesis) such as indomethacin or a special form of ibuprofen have been used to initiate PDA closure.[1][7][8] Recent findings from a systematic review concluded that, for closure of a PDA in preterm and/or low birth weight infants, ibuprofen is as effective as indomethacin. It also causes fewer side effects (such as transient acute kidney injury) and reduces the risk of necrotising enterocolitis.[9] A review and meta-analysis showed that paracetamol may be effective for closure of a PDA in preterm infants.[10] A recent network meta-analysis that compared indomethacin, paracetamol and ibuprofen at different doses and administration schemes among them found that a high dose of oral ibuprofen may offer the highest likelihood of closure in preterm infants.[11]

While indomethacin can be used to close a PDA, some neonates require their PDA be kept open. Keeping a ductus arteriosus patent is indicated in neonates born with concurrent heart malformations, such as transposition of the great arteries. Drugs such as alprostadil, a PGE-1 analog, can be used to keep a PDA open until the primary defect is corrected surgically.

Prognosis

If left untreated, the disease may progress from left-to-right shunt (acyanotic heart) to right-to-left shunt (cyanotic heart), called Eisenmenger's syndrome. Pulmonary hypertension is a potential long-term outcome, which may require a heart and/or lung transplant. Another complication of PDA is intraventricular hemorrhage.

History

Robert E. Gross, MD performed the first successful ligation of a patent ductus arteriosus on a seven-year-old girl at Children's Hospital Boston in 1938.[12]

Adult

Since PDA is usually identified in infants, it is less common in adults, but it can have serious consequences, and is usually corrected surgically upon diagnosis.

See also

References

- MedlinePlus > Patent ductus arteriosus Update Date: 21 December 2009

- "Tests and Diagnosis". Mayo Clinic. 16 December 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Fowlie, PW; Davis PG; McGuire W (19 May 2010). "Prophylactic intravenous indomethacin for preventing mortality and morbidity in preterm infants (Review)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD000174. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000174.pub2. PMC 7045285. PMID 20614421.

- Zahaka, KG and Patel, CR. "Congenital defects'". Fanaroff, AA and Martin, RJ (eds.). Neonatal-perinatal medicine: Diseases of the fetus and infant. 7th ed. (2002):1120–1139. St. Louis: Mosby.

- Mosalli R, Alfaleh K, Paes B (July 2009). "Role of prophylactic surgical ligation of patent ductus arteriosus in extremely low birth weight infants: Systematic review and implications for clinical practice". Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2 (2): 120–6. doi:10.4103/0974-2069.58313. PMC 2922659. PMID 20808624.

- Alejandra Martins (2 October 2014). "The inventions of the Bolivian doctor who saved thousands of children". BBC Mundo. Retrieved 30 March 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- circ.ahajournals.org

- MayoClinic > Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). 22 Dec. 2009

- Ohlsson A, Walia R, Shah SS (2015). "Ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight (or both) infants". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003481. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003481.pub6. PMID 25692606.

- Ohlsson, Arne; Shah, Prakeshkumar S. (27 January 2020). "Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight infants". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD010061. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010061.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6984659. PMID 31985831.

- Mitra, Souvik; Florez, Ivan D.; Tamayo, Maria E.; Mbuagbaw, Lawrence; Vanniyasingam, Thuva; Veroniki, Areti Angeliki; Zea, Adriana M.; Zhang, Yuan; Sadeghirad, Behnam (27 March 2018). "Association of Placebo, Indomethacin, Ibuprofen, and Acetaminophen With Closure of Hemodynamically Significant Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants". JAMA. 319 (12): 1221–1238. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.1896. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 5885871. PMID 29584842.

- , Robert E. Gross, Harvard Medical School Office for Faculty Affairs.

External links

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus Causes from US Department of Health and Human Services

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus from Merck

- Patent ductus arteriosus information for parents.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |