Parshvanatha

Parshvanatha (Pārśvanātha), also known as Parshva (Pārśva) and Paras, was the 23rd of 24 tirthankaras (ford-makers or propagators of dharma) of Jainism. He is one of the earliest tirthankaras who are acknowledged as historical figures. He was the earliest exponent of Karma philosophy in recorded history. The Jain sources place him between the 9th and 8th centuries BC whereas historians point out that he lived in the 8th or 7th century BC.[4] Parshvanatha was born 273 years before Mahavira. He was the spiritual successor of 22nd tirthankara Neminath. He is popularly seen as a propagator and reviver of Jainism. Parshvanatha attained moksha on Mount Sammeta (Madhuban, Jharkhand) in the Ganges basin, an important Jain pilgrimage site. His iconography is notable for the serpent hood over his head, and his worship often includes Dharanendra and Padmavati (Jainism's serpent god and goddess).

| Parshvanatha | |

|---|---|

23rd Jain Tirthankara | |

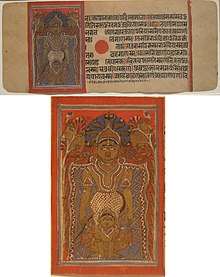

Image of Tīrthankara Parshvanatha (Victoria and Albert Museum, 6th–7th Century) | |

| Other names | Pārśva, Paras |

| Venerated in | Jainism |

| Predecessor | Neminatha |

| Successor | Mahavira |

| Symbol | Snake[1] |

| Height | 9 cubits (13.5 feet) [2] |

| Age | 100 years |

| Tree | Ashok |

| Color | Green |

| Personal information | |

| Born | c. 872 BC[3] |

| Died | c. 772 BC[3] |

| Parents |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Ethics |

|

Major sects |

|

Texts |

|

Festivals

|

|

|

According to Jain texts, Parshvanatha was born in Banaras (Varanasi), India. Renouncing worldly life, he founded an ascetic community. Texts of the two major Jain sects (Digambaras and Śvētāmbaras) differ on the teachings of Parshvanatha and Mahavira, and this is a foundation of the dispute between the two sects. The Digambaras believe that there was no difference between the teachings of Parshvanatha and Mahavira. According to the Śvētāmbaras, Mahavira expanded Parshvanatha's first four restraints with his ideas on ahimsa (non-violence) and added the fifth monastic vow (celibacy). Parshvanatha did not require celibacy, and allowed monks to wear simple outer garments. Śvētāmbara texts, such as section 2.15 of the Acharanga Sutra, say that Mahavira's parents were followers of Parshvanatha (linking Mahavira to a preexisting theology as a reformer of Jain mendicant tradition).

Historicity

Parshvanatha is the earliest Jain tirthankara who is generally acknowledged as a historical figure.[5][6][7] According to Paul Dundas, Jain texts such as section 31 of Isibhasiyam provide circumstantial evidence that he lived in ancient India.[8] Historians such as Hermann Jacobi have accepted him as a historical figure because his Chaturyama Dharma (Four Vows) are mentioned in Buddhist texts.[9]

Despite the accepted historicity, some historical claims (such as the link between him and Mahavira, whether Mahavira renounced in the ascetic tradition of Parshvanatha and other biographical details) have led to different scholarly conclusions.[10] He is claimed in Jain texts to have been 13.5 feet (4.1 m) tall.[2]

Parshvanatha's biography is legendary, with Jain texts saying that he preceded Mahavira by 273 years and that he lived 100 years.[11][3] Mahavira is dated to c. 599 – c. 527 BC in the Jain tradition, and Parshvanatha is dated to c. 872 – c. 772 BC.[11][12][13] According to Dundas, historians outside the Jain tradition date Mahavira as contemporaneous with the Buddha in the 5th century BC and, based on the 273-year gap, date Parshvanatha to the 8th or 7th century BC.[3]

Doubts about Parshvanatha's historicity are supported by the oldest Jain texts, which present Mahavira with sporadic mentions of ancient ascetics and teachers without specific names (such as sections 1.4.1 and 1.6.3 of the Acaranga Sutra).[14] The earliest layer of Jain literature on cosmology and universal history pivots around two jinas: the Adinatha (Rishabhanatha) and Mahavira. Stories of Parshvanatha and Neminatha appear in later Jain texts, with the Kalpa Sūtra the first known text. However, these texts present the tirthankaras with unusual, non-human physical dimensions; the characters lack individuality or depth, and the brief descriptions of three tirthankaras are largely modeled on Mahavira.[15] Their bodies are celestial, like deva. The Kalpa Sūtra is the most ancient known Jain text with the 24 tirthankaras, but it lists 20; three, including Parshvanatha, have brief descriptions compared with Mahavira.[15][16] Early archaeological finds, such as the statues and reliefs near Mathura, lack iconography such as lions or serpents (possibly because these symbols evolved later).[15][17]

Jain biography

Parshvanatha was the 23rd of 24 tirthankaras in Jain tradition.[19]

Life before renunciation

He was born on the tenth day of the dark half of the Hindu month of Pausha to King Ashwasena and Queen Vamadevi of Varanasi .[20][8][21] Parshvanatha belonged to the Ikshvaku dynasty.[22][23] Before his birth, Jain texts state that he ruled as the god Indra in the 13th heaven of Jain cosmology.[24] While Parshvanatha was in his mother's womb, gods performed the garbha-kalyana (enlivened the fetus).[25] His mother dreamt sixteen auspicious dreams, an indicator in Jain tradition that a tirthankara was about to be born.[25] According to the Jain texts, the thrones of the Indras shook when he was born and the Indras came down to earth to celebrate his janma-kalyanaka (his auspicious birth).[26]

Parshvanatha was born with blue-black skin. A strong, handsome boy, he played with the gods of water, hills and trees.[26] At the age of eight, Parshvanatha began practicing the twelve basic duties of the adult Jain householder.[26][note 1]

He lived as a prince and soldier in Varanasi .[28] According to the Digambara school, Parshvanatha never married; Śvētāmbara texts say that he married Prabhavati, the daughter of Prasenajit (king of Kusasthala).[29][30] Heinrich Zimmer translated a Jain text that sixteen-year-old Parshvanatha refused to marry when his father told him to do so; he began meditating instead, because the "soul is its only friend".[31]

Renunciation

At age 30, on the 11th day of the moon's waxing in the month of Pausha (December–January), Parshvanatha renounced the world to become a monk.[32][33] He removed his clothes and hair, and began fasting strictly.[34] Parshvanatha meditated for 84 days before he attained omniscience under a dhaataki tree near Benares.[35] His meditation period included asceticism and strict vows. Parshvanatha's practices included careful movement, measured speech, guarded desires, mental restraint and physical activity, essential in Jain tradition to renounce the ego.[34] According to the Jain texts, lions and fawns played around him during his asceticism.[33][note 2]

On the 14th day of the moon's waning cycle in the month of Chaitra (March–April), Parshvanatha attained omniscience.[37] Heavenly beings built him a samavasarana (preaching hall), so he could share his knowledge with his followers.[38]

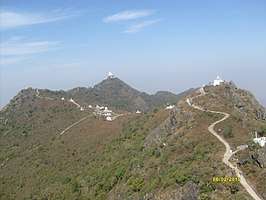

After preaching for 70 years, Parshvanatha attained moksha at Shikharji on Parasnath hill[note 3][41][42] at the age of 78 on Savana Shukla Saptami according to Lunar Calendar.[8] His death is considered moksha (liberation from the cycle of birth and death) in Jain tradition[21] and celebrated as Moksha Saptami. This day is celebrated on large scale at Parasnath tonk of the mountain, in northern Jharkhand, part of the Parasnath Range[43] by offering Nirvana Laddu (Sugar balls) and reciting of Nirvana Kanda. Parshvanatha has been called purisādāṇīya (beloved of the people) by Jains.[44][45][46]

Previous lives

Jain mythology contains legends about Parshvanatha's human and animal rebirths and the maturing of his soul towards inner harmony in a manner similar to legends found in other Indian religions.[47][note 4] His rebirths include:[49]

- Marubhuti – Vishwabhuti, King Aravinda's prime minister, had two sons; the elder one was Kamath and the younger one was Marubhuti (Parshvanatha). Kamath committed adultery with Marubhuti's wife. The king learnt about the adultery, and asked Marubhuti how his brother should be punished; Marubhuti suggested forgiveness. Kamath went into a forest, became an ascetic and acquired demonic powers to take revenge. Marubhuti went to the forest to invite his brother back home, but Kamath killed Marubhuti by crushing him with a stone. Marubhuti was one of Parshvanatha's earlier rebirths.[50]

- Vajraghosha (Thunder), an elephant – He was then reborn as an elephant because of the "violence of the death and distressing thoughts he harbored at the time of his previous death".[51] Vajraghosha lived in the forests of Vindyachal.[52] Kamath was reborn as a serpent.[52] King Aravinda, after the death of his minister's son, renounced his throne and led an ascetic life. When an angry Vajraghosha approached Aravinda, the ascetic saw that the elephant was the reborn Marubhuti. Aravinda asked the elephant to give up "sinful acts, remove his demerits from the past, realize that injuring other beings is the greatest sin, and begin practicing the vows".[51] The elephant realized his error, became calm, and bowed at Aravinda's feet. When Vajraghosha went to a river one day to drink, the serpent Kamath bit him. He died peacefully this time, however, without distressing thoughts.[53]

- Sasiprabha – Vajraghosha was reborn as Sashiprabha (Lord of the Moon)[note 5] in the twelfth heaven, surrounded by abundant pleasures. Sashiprabha, however, did not let the pleasures distract him and continued his ascetic life.[53]

- Agnivega – Sashiprabha died, and was reborn as Prince Agnivega ("strength of fire"). After he became king, he met a sage who told him about the impermanence of all things and the significance of a spiritual life. Agnivega realized the importance of religious pursuits, and his worldly life lost its charms. He renounced it to lead an ascetic life, joining the sage's monastic community.[53] Agnivega meditated in the Himalayas, reducing his attachment to the outside world. He was bitten by a snake (the reborn Kamath), but the poison did not disturb his inner peace and he calmly accepted his death.[57]

Agnivega was reborn as a god with a life of "twenty-two oceans of years", and the serpent went to the sixth hell.[57] The soul of Marubhuti-Vajraghosa-Sasiprabha-Agnivega was reborn as Parshvanatha. He saved serpents from torture and death during that life; the serpent god Dharanendra and the goddess Padmavati protected him, and are part of Parshvanatha's iconography.[11][58]

Disciples

According to the Kalpa Sūtra (a Śvētāmbara text), Parshvanatha had 164,000 śrāvakas (male lay followers), 327,000 śrāvikās (female lay followers), 16,000 sādhus (monks) and 38,000 Sadhvis or aryikas (nuns).[59][60][49] According to Śvētāmbara tradition, he had eight ganadharas (chief monks): Śubhadatta, Āryaghoṣa, Vasiṣṭha, Brahmacāri, Soma, Śrīdhara, Vīrabhadra and Yaśas.[43] After his death, the Śvētāmbara believe that Śubhadatta became head of the monastic order and was succeeded by Haridatta, Āryasamudra and Keśī.[32]

According to Digambara tradition (including the Avasyaka niryukti), Parshvanatha had 10 ganadharas and Svayambhu was their leader. Śvētāmbara texts such as the Samavayanga and Kalpa Sūtras cite Pushpakula as the chief aryika of his female followers,[59] but the Digambara Tiloyapannati text identifies her as Suloka or Sulocana.[30] Parshvanatha's nirgrantha (without bonds) monastic tradition was influential in ancient India, with Mahavira's parents part of it as lay householders who supported the ascetics.[61]

Teachings

Texts of the two major Jain sects (Digambara and Śvētāmbara) have different views of Parshvanatha and Mahavira's teachings, which underlie disputes between the sects.[62][63][64][65] Digambaras maintain that no difference exists between the teachings of Parshvanatha and Mahavira.[63] According to the Śvētāmbaras, Mahavira expanded the scope of Parshvanatha's first four restraints with his ideas on ahimsa (non-violence) and added the fifth monastic vow (celibacy) to the practice of asceticism.[66] Parshvanatha did not require celibacy,[67] and allowed monks to wear simple outer garments.[62][68] Śvētāmbara texts such as section 2.15 of the Acharanga Sutra say that Mahavira's parents were followers of Parshvanatha,[69] linking Mahavira to a preexisting theology as a reformer of Jain mendicant tradition.

According to the Śvētāmbara tradition, Parshvanatha and the ascetic community he founded exercised a fourfold restraint;[70][71] Mahavira stipulated five great vows for his ascetic initiation.[70][72] This difference and its reason have often been discussed in Śvētāmbara texts.[73] The Uttardhyayana Sutra[74][75] (a Śvētāmbara text) describes Keśin Dālbhya as a follower of Parshvanatha and Gautama Buddha as a disciple of Mahavira and discusses which doctrine is true: the fourfold restraint or the five great vows.[76] Gautama says that there are outward differences, and these differences are "because the moral and intellectual capabilities of the followers of the ford-makers have differed".[77] According to Wendy Doniger, Parshvanatha allowed monks to wear clothes; Mahavira recommended nude asceticism, a practice which has been a significant difference between the Digambara and Śvētāmbara traditions.[78][79]

According to the Śvētāmbara texts, Parshvanatha's four restraints were ahimsa, aparigraha (non-possession), asteya (non-stealing) and satya (non-lying).[11] Ancient Buddhist texts (such as the Samaññaphala Sutta) which mention Jain ideas and Mahavira cite the four restraints, rather than the five vows of later Jain texts. This has led scholars such as Hermann Jacobi to say that when Mahavira and the Buddha met, the Buddhists knew only about the four restraints of the Parshvanatha tradition.[65] Further scholarship suggests a more-complex situation, because some of the earliest Jain literature (such as section 1.8.1 of the Acharanga Sutra) connects Mahavira with three restraints: non-violence, non-lying and non-possession.[80]

The "less than five vows" view of Śvētāmbara texts is not accepted by the Digambaras, a tradition whose canonical texts have been lost and who do not accept Śvētāmbara texts as canonical.[65] Digambaras have a sizable literature, however, which explains their disagreement with Śvētāmbara interpretations.[65] Prafulla Modi rejects the theory of differences between Parshvanatha's and Mahavira's teachings.[63] Champat Rai Jain writes that Śvētāmbara texts insist on celibacy for their monks (the fifth vow in Mahavira's teachings), and there must not have been a difference between the teachings of Parshvanatha and Mahavira.[81]

Padmanabh Jaini writes that the Digambaras interpret "fourfold" as referring "not to four specific vows", but to "four modalities" (which were adapted by Mahavira into five vows).[82] Western and some Indian scholarship "has been essentially Śvētāmbara scholarship", and has largely ignored Digambara literature related to the controversy about Parshvanatha's and Mahavira's teachings.[82] Paul Dundas writes that medieval Jain literature, such as that by the 9th-century Silanka, suggests that the practices of "not using another's property without their explicit permission" and celibacy were interpreted as part of non-possession.[80]

In literature

- Uvasagharam Stotra is an ode to Parshvanatha which was written by Bhadrabahu.

- Jinasena's Mahapurāṇa includes "Ādi purāṇa" and Uttarapurana. It was completed by Jinasena's 8th-century disciple, Gunabhadra. "Ādi purāṇa" describes the lives of Rishabhanatha, Bahubali and Bharata.[83] The Kalpa Sūtra contains biographies of the tirthankaras Parshvanatha and Mahavira.

- Guru Gobind Singh wrote a biography of Parshvanatha in the 17th-century Paranath Avtar, part of the Dasam Granth.[84][85]

- Sankhesvara Stotram is hymn to Parshvanatha compiled by Mahopadhyaya Yashovijya.[86]

Iconography

Parshvanatha is a popular tirthankara who is worshiped (bhakti) with Rishabhanatha, Shantinatha, Neminatha and Mahavira.[87][88] He is believed to have the power to remove obstacles and save devotees.[89]

Parshvanatha is usually depicted in a lotus or kayotsarga posture. Statues and paintings show his head shielded by a multi-headed serpent, fanned out like an umbrella. Parshvanatha's snake emblem is carved (or stamped) beneath his legs as an icon identifier. His iconography is usually accompanied by Dharnendra and Padmavati, Jainism's snake god and goddess.[11][58]

Serpent-hood iconography is not unique to Parshvanatha; it is also found above the icons of Suparshvanatha, the seventh of the 24 tirthankaras, but with a small difference.[90] Suparshvanatha's serpent hood has five heads, and a seven (or more)-headed serpent is found in Parshvanatha icons. Statues of both tirthankaras with serpent hoods have been found in Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, dating to the 5th to 10th centuries.[91][92]

Archeological sites and medieval Parshvantha iconography found in temples and caves include scenes and yaksha. Digambara and Śvētāmbara iconography differs; Śvētāmbara art shows Parshvanatha with a serpent hood and a Ganesha-like yaksha, and Digambara art depicts him with serpent hood and Dhranendra.[93][94] According to Umakant Premanand Shah, Hindu gods (such as Ganesha) as yaksha and Indra as serving Parshvanatha, assigned them to a subordinate position.[95]

- Uttar Pradesh, 2nd century (Museum of Oriental Art)

5th century (Satna, Madhya Pradesh)

5th century (Satna, Madhya Pradesh) 6th century, Uttar Pradesh

6th century, Uttar Pradesh- 7th-century Akota Bronze (Honolulu Museum of Art)

- Mathura, 8th century (Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm)

- 8th-century brass, Ethnological Museum of Berlin

9th century - Cleveland Museum of Art

9th century - Cleveland Museum of Art 10th-century copper, inlaid with silver and gemstones (LACMA)

10th-century copper, inlaid with silver and gemstones (LACMA) 11th century - Freer Gallery of Art

11th century - Freer Gallery of Art.jpg) 10th century, Asian Civilisations Museum

10th century, Asian Civilisations Museum- 11th century, Maharaja Chhatrasal Museum

%2C_xii_secolo.jpg) Karnataka, 12th century (Art Institute of Chicago)

Karnataka, 12th century (Art Institute of Chicago).jpg) 1813 engraving

1813 engraving

Colossal statues

- The Navagraha Jain Temple has the tallest statue of Parshvanatha: 61 feet (18.6 m), on a 48-foot (14.6-m) pedestal. The statue, in the kayotsarga position, weighs about 185 tons.[98]

- The Gopachal rock cut Jain monuments were built between 1398 and 1536. The largest cross-legged statue of Parshvanatha – 47 feet (14 m) tall and 30 feet (9.1 m) wide – is in one of the caves.[99]

- A 10th-century temple in Shravanabelagola enshrines an 18-foot-tall (5.5 m) statue of Parshvanatha in a kayotsarga position.[100]

- Parshvanatha basadi, Halebidu, built by Boppadeva in 1133, contains an 18-foot (5.5 m) black granite kayotsarga statue of Parshvanatha.[101]

- A 31-foot (9.4 m) kayotsarga statue was installed in 2011 at the Vahelna Jain Temple.[102]

- VMC has approved construction of 100 foot tall statue in Sama pond in Vadodara.[103]

Parsvanatha Temple in Shravanabelgola

Parsvanatha Temple in Shravanabelgola

Temples

- Shikharji (Sammet Sikhar) in Jharkhand

- Mirpur Jain Temple

- Shri Shankeshwar Tirth[49]

- Andeshwar Parshwanath in Rajasthan

- Bada Gaon

- Kallil Temple, Kerala

- Navagraha Jain Temple in Hubli, Karnataka

- Gajpanth

- Mel Sithamur Jain Math

- Pateriaji

- Nainagiri

- Kundadri

- Kanakagiri Jain tirth

See also

Notes

- According to Zimmer, the Tattvarthadhigama Sutra state the twelve householder vows to be: (1) do not kill any being, (2) do not lie, (3) do not use another's property without permission, (4) be chaste, (5) limit your possessions, (6) take a perpetual and daily vow to go only certain distances and take only certain directions, (7) avoid useless talk and action, (8) do not think sinful acts, (9) limit diet and enjoyments, (10) worship at fixed times in the morning, noon and evening, (11) fast on some days and (12) give charity by donating knowledge, money and such everyday.[27]

- Jain mythology describes a heavenly being attempting to distract (or harm) Parshvanatha, but the serpent god Dharanendra and the goddess Padmavati guard his journey to omniscience.[36]

- Some texts call the place Mount Sammeta.[39] It is revered in Jainism because 20 of its 24 tirthankaras are believed to have attained moksha there.[40]

- The Jataka tales, for example, describe the Buddha's previous lives.[48]

- Also known as Chandraprabha,[54] he also appears in Buddhist and Hindu mythology[55] and is the eighth of twenty-four entities in Jain cosmology.[56]

References

Citations

- Tandon 2002, p. 45.

- Sarasvati 1970, p. 444.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 30–31.

- "Rude Travel: Down The Sages Vir Sanghavi".

- Heehs 2002, p. 90.

- Jaini 2001, p. 62.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 182–183, 220.

- Dundas 2002, p. 30.

- Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 11.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 30–33.

- Britannica 2009.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 183.

- Martin & Runzo 2001, pp. 200–201.

- Dundas 2002, p. 39.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 39–40.

- Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 83–84.

- Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 82–85, Quote: "Thus the list of twenty-four Tirthankaras was either already evolved or was in the process of being evolved in the age of the Mathura sculptures in the first three centuries of the Christian era.".

- Jacobi 1964, p. 271.

- Fisher 1997, p. 115.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 184.

- Sangave 2001, p. 104.

- Ghatage 1951, p. 411.

- Deo 1956, p. 60.

- Zimmer 1953, pp. 183–184.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 194–196.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 196.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 196 with footnote 14.

- Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 208.

- Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 12.

- Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 171.

- Zimmer 1953, pp. 199–200.

- von Glasenapp 1999, pp. 24–28.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 201.

- Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 325.

- Danielou 1971, p. 376.

- Zimmer 1953, pp. 201–203.

- Zimmer 1953, pp. 202–203.

- Zimmer 1953, pp. 203–204.

- Jacobi 1964, p. 275.

- Cort 2010, pp. 130–133.

- Wiley 2009, p. 148.

- Dundas 2002, p. 221.

- Kailash Chand Jain 1991, p. 13.

- Jacobi 1964, p. 271 with footnote 1.

- Kailash Chand Jain 1991, pp. 12–13.

- Schubring 1964, p. 220.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 187–188.

- Jataka Archived 25 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia Britannica (2010)

- Clines 2017, pp. 867–872.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 186–187.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 189.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 189–190.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 190.

- Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 107, Quote: In Paimacariyam, Candraprabha is called Sasiprabha".

- Paul Williams 2005, pp. 127–130.

- Coulter 2013, p. 121.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 191.

- Cort 2010, pp. 26, 134, 186.

- Jacobi 1964, p. 274.

- Cort 2001, p. 47.

- Dalal 2010, p. 220.

- Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 211.

- Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 5.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 31–33.

- Jaini 2000, pp. 27–28.

- Chapple 2011, pp. 263–267.

- Kenoyer & Heuston 2005, pp. 96–98.

- Hoiberg 2000, p. 158.

- Heehs 2002, pp. 90–91.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 30–32.

- Jaini 1998, p. 17.

- Price 2010, p. 90.

- Jaini 1998, pp. 13–18.

- Jaini 1998, p. 14.

- Jaini 2000, p. 17.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 31–32.

- Dundas 2002, p. 31.

- Doniger 1999, p. 843.

- Long 2009, pp. 62–67.

- Dundas 2002, p. 283 with note 30.

- Champat Rai Jain 1939, p. 102–103.

- Jaini 2000, pp. 28–29.

- Upadhye 2000, p. 46.

- Bhattacharya 2011, p. 270.

- Mansukhani 1993, p. 6.

- Suriji 2013, p. 5.

- Dundas 2002, p. 40.

- Cort 2010, pp. 86, 95–98, 132–133.

- Dundas 2002, pp. 33, 40.

- Cort 2010, pp. 278–279.

- Harvard. "From the Harvard Art Museums' collections Tirthankara Suparsvanatha in Kayotsarga, or Standing Meditation, Posture and Protected by a Five-Headed Naga". www.harvardartmuseums.org. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- Pal, Huyler & Cort 2016, p. 204.

- Brown 1991, pp. 105–106.

- Pal 1995, p. 87.

- Umakant P. Shah 1987, pp. 220–221.

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 201. ISBN 9789004155374.

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 406, photograph and date. ISBN 9789004155374.

- Hubli gets magnificent 'jinalaya'. The Hindu, 6 January 2009.

- "Welcome to official website of District Administration Gwalior (M.P.) India". gwalior.nic.in. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "Shravanabelagola- A Unique Destination". Anand Bharat. 22 October 2016. Archived from the original on 7 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Parsvanatha Basti, Halebid". Archaeological Survey of India. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- Vahelna & Government of Uttar Pradesh.

- Times of India & 100-feet Parshwanath idol.

Sources

- Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi (2011), Approaches to History: Essays in Indian Historiography, Primus Books, ISBN 9789380607177

- Brown, Robert L. (1991), Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-0656-4

- Chapple, Christopher K (2011), Andrew R. Murphy (ed.), The Blackwell Companion to Religion and Violence, John Wiley, ISBN 978-1-4443-9573-0

- Clines, Gregory M. (2017), "Pārśvanātha (Jainism)", in Sarao, K. T. S.; Long, Jeffery D. (eds.), Buddhism and Jainism, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, Springer Netherlands, ISBN 978-94-024-0851-5

- Cort, John E. (2001), Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9

- Cort, John E. (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Coulter, Charles Russell (2013), Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-96390-3

- Danielou, A (1971), L'Histoire de l'Inde Translated from French by Kenneth Hurry, ISBN 978-0-89281-923-2

- Deo, Shantaram Bhalchandra (1956), History of Jaina monachism from inscriptions and literature, Pune: Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute

- Dalal, Roshen (2010), The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (1999), Encyclopedia of World Religions, Merriam-Webster, ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-26605-5

- Parshvanatha: Jaina Saint, in Encyclopaedia Britannica, Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2009

- Fisher, Mary Pat (1997), Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World's Faiths, London: I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1-86064-148-0

- Ghatage, A.M. (1951), "Jainism", in Majumdar, R.C.; Pusalker, A.D. (eds.), The Age of Imperial Unity, Bombay

- Heehs, Peter (2002), Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience, New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-3650-0

- Hoiberg, Dale (2000), Students' Britannica India, Volume 4: Miraj to Shastri, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5

- Jacobi, Hermann (1964), Max Muller (The Sacred Books of the East Series, Volume XXII) (ed.), Jaina Sutras (Translation), Motilal Banarsidass (Original: Oxford University Press)

- Jain, Champat Rai (1939), The Change of Heart

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1991), Lord Mahāvīra and His Times, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1578-0

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2001), Collected Papers on Buddhist Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1776-0

- Jaini, Padmanabh S., ed. (2000), Collected Papers On Jaina Studies (First ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1691-6

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006), Encyclopedia of Hinduism (PDF), Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5

- Long, Jeffery D. (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, I. B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84511-625-5

- Kenoyer, Jonathan M.; Heuston, Kimberley Burton (2005), The Ancient South Asian World, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-522243-2

- Mansukhani, Gobind Singh (1993), Hymns from the Dasam Granth, Hemkunt Press, ISBN 9788170101802

- Martin, Nancy M.; Runzo, Joseph (2001), Ethics in the World Religions, Oneworld Publications, ISBN 978-1-85168-247-8

- Pal, Pratapaditya (1995), Ganesh, the Benevolent, Marg Publications, ISBN 978-81-85026-31-2

- Pal, Pratapaditya; Huyler, Stephen P.; Cort, John E. (2016), Puja and Piety: Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist Art from the Indian Subcontinent, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-28847-8

- Price, Joan (2010), Sacred Scriptures of the World Religions: An Introduction, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-0-8264-2354-2

- Sangave, Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Sarasvati, Swami Dayananda (1970), An English translation of the Satyarth Prakash, Swami Dayananda Sarasvati

- Schubring, Walther (1964), Jinismus, in: Die Religionen Indiens, 3, Stuttgart

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6

- Tandon, Om Prakash (2002) [1968], Jaina Shrines in India (1 ed.), New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, ISBN 978-81-230-1013-7

- Upadhye, Dr. A. N. (2000), Mahāvīra His Times and His philosophy of life, Bharatiya Jnanpith

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1999), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009) [1949], The A to Z of Jainism, 38, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6337-8

- Williams, Paul, ed. (2005), Buddhism: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-33226-2

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6CS1 maint: location (link)

- "100-feet Parshwanath idol gets Vadodara civic body nod". The Times of India. 27 July 2019.

- Suriji, Acharya Kalyanbodhi (2013), Sankhesvara Stotram, Multy Graphics

- "Vahelna - Jain temple". Government of Uttar Pradesh.

External links

_(8638423582).jpg)