Paleomerus

Paleomerus is a genus of strabopid, a group of extinct arthropods. It has been found in deposits from the Cambrian period (Atdabanian epoch). It is classified in the family Strabopidae of the monotypic order Strabopida. It contains two species, P. hamiltoni from Sweden and P. makowskii from Poland. The generic name is composed by the Ancient Greek words παλαιός (palaiós), meaning "ancient", and μέρος (méros), meaning "part" (and therefore, "ancient part").

| Paleomerus | |

|---|---|

| |

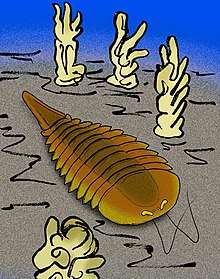

| Restoration of P. hamiltoni. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| (unranked): | Tactopoda |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Clade: | Arachnomorpha |

| Order: | †Strabopida |

| Family: | †Strabopidae |

| Genus: | †Paleomerus Størmer, 1956 |

| Type species | |

| †Paleomerus hamiltoni Størmer, 1956 | |

| Species | |

| |

Paleomerus is one of the oldest arthropods, being sometimes interpreted as the model of the first arachnomorphs. It is part of the order Strabopida, a poorly known group closely related to the aglaspidids of uncertain affinities, often being ignored by researchers and authors due to the poor preservation and abundance of their fossils. It has been suggested that Paleomerus and the closely related Strabops could be synonymous with each other, since they differ only in the size of the telson ("tail") and the position of the eyes. These two genera were originally deferred by a hypothetical twelfth segment in Paleomerus, but after the discovery and description of a fourth specimen of P. hamiltoni, it has been shown that this segment actually represents the tail of the animal.

Description

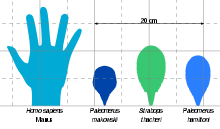

As the other strabopids, Paleomerus was a small-sized arthropod. The bigger species was P. hamiltoni at 9.3 centimetres (3.7 inches),[1] while the smaller P. makowskii reached only 7.3 cm (2.9 in).[2] Other Cambrian arthropods reached much greater lengths, such as the gigantic anomalocarid genus Anomalocaris that surpassed 1 m (3 ft 3 in).[3] Within Strabopida, the closely related Strabops thacheri exceeded the length of Paleomerus with 11 cm (4.3 in),[4] while Parapaleomerus sinensis reached a total length of 9.2 cm (3.6 in).[5]

Like some other arthropod clades, the strabopids possessed segmented bodies and jointed appendages (limbs) covered in a cuticle composed of proteins and chitin. The arthropod body is divided into two tagmata (sections); the frontal prosoma (head) and posterior opisthosoma (abdomen). The appendages were attached to the prosoma, and although they are unknown in strabopids (except for one undescribed specimen of Parapaleomerus[5]), it is most likely they owned several pairs of them.[6] Although the chemical composition of the strabopid exoskeleton is unknown, it was probably mineralized (with inorganic substances),[7] sturdy and calcareous (containing calcium). The head of the strabopids was very short, the back was rounded and lacked trilobation (being divided in three lobes), the abdomen was composed by eleven segments and succeeded by a thick tail spine, the telson.[8][5] In Paleomerus, the prosoma was parabolic (approximately U-shaped), and the opisthosoma can increase or decrease in width slightly or strongly.[2] It was very flexible, possibly being able to flex laterally and roll up itself.[1] The telson was trapezoidal,[9] broad and tapering. Paleomerus may be the best model of a primitive arachnomorph.[10]

Paleomerus differs from Strabops only in the position of the eyes, which are farther from each other and closer to the margin than in Strabops,[8] and the size of the telson, being shorter and broader than in the latter.[9]

History of research

Paleomerus has two species described; all other described strabopid genera are monotypic. The Norwegian paleontologist and geologist Leif Størmer erected the genus based on two specimens (Ar. 47071, holotype, and Ar. 47073, the paratype) and tentatively classified it under the order Aglaspida in its own family, Paleomeriidae (also spelled Paleomeridae[9]). Paleomerus is translated to "ancient part", with its name derived from the Ancient Greek words παλαιός (palaiós, ancient) and μέρος (méros, part). The designated type species, P. hamiltoni, is named after Count Hugo Hamilton, who sent both fossils to the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm. In this species, the prosoma was short and had a parabolic shape with a somewhat concave posterior border. The posterolateral borders were rounded and lacked spines. The compound eyes appear as anterolateral reniform (bean-shaped) elevations in the surface of the prosoma. The opisthosoma increased slightly its width in the third and fourth segments, then decreased slightly until the seventh segment. All the tergites (the dorsal part of the segments) were similar, superimposing strongly on each other, with the half of the first segment being hidden under the prosoma. The rest of tergites were more slightly superimposed, indicating a great flexibility and even the ability to roll up itself. The telson was trapezoidal, but Størmer mistook it as the twelfth segment of the body, suggesting a hypothetical lanceolate (lance-shaped) or fan-shaped telson. It is estimated that the size of this species was of 9.3 cm (3.7 in) judging by the length of the paratype.[1]

In 1971, the Swedish geologist and paleontologist Jan Bergström described a new specimen of P. hamiltoni, RM Ar. 47170, found in the same place as the previous two. This new poorly preserved fossil contains molds of the first eleven segments, with a total corporal length estimated at 6.4 cm (2.5 in, being slightly larger than the holotype). Bergström tentatively removed Strabopidae (at that time containing Strabops and Neostrabops) and Paleomeridae (only Paleomerus) from the order Aglaspidida based on the fact that the head tagma was too short to accommodate the six pairs of appendages then assumed to be present in aglaspidids. Instead, he classified them in an uncertain order in the Merostomoidea class together with the emeraldellids. Ironically, Bergström speculated that the number of pairs of appendages present in the three genera could be fewer than seven, as well as including a possible antennal segment.[7] This is currently observed as an overestimate.[9] A study published by Derek Ernest Gilmor Briggs et al. in 1979 has shown that the aglaspidid Aglaspis spinifer had between four and five pairs of appendages, but not six, weakening Bergström's argument.[11]

In 1983, the Polish paleontologist Stanisław Orłowski described a second species of Paleomerus from the Ociesęki Sandstone Formation. Named Paleomerus makowskii, the specific name of this species honors the professor Henryk Makowski and is known by only one specimen with an almost completely preserved exoskeleton (IGPUW/Ag/1/1, housed at the Geological Faculty, Warsaw University). In this species, the exoskeleton was ovate, increasing its width from the prosoma to the fifth segment and rapidly decreasing posteriorly. It had a convex shape, with the second and third segments being the most convex. The prosoma was smooth, short, rounded on the front and with somewhat concave posterior borders. It was 1.7 cm (0.7 in) long and 4.2 cm (1.6 in) wide. The eyes were placed anterolaterally and rose slightly from the surface of the prosoma, with the left eye being the only one preserved. While segments 1-4 are complete, segments 5-10 are partially destroyed. The first ten segments are all alike, overlapping each other almost half the length in each segment. The eleventh was very different from the rest, being longer and less broad and with a straight anterior border. Both sides bent downwards and the posterior border was rounded. This segment measured approximately 1.1 cm (0.4 in) in length and 1.9 cm (0.7 in) in width. The telson was flat and trapezoidal, with the posterior edge being concave, although this may be due to poor preservation.[9] It measured 1.3 cm (0.5 in) long and 2 cm (0.8 in) wide. Following Størmer, Orłowski interpreted the telson as the twelfth segment. The total length of P. makowskii is estimated at 7.3 cm (2.9 in), with a maximum width of 5 cm (2 in). Although the outline of the body and the proportions between the prosoma and opisthosoma suggest an assignment to Paleomerus, P. makowskii differs from P. hamiltoni in its great width and in the form of the eleventh segment and telson, as well as in the eyes, placed in elevations with vertical and straight lateral walls.[2]

In 1997, Bergström and his partner Hou Xianguang, a Chinese paleontologist, completely removed Strabopidae (recognizing Paleomeridae as a junior synonym), as well as the family Lemoneitidae (containing Lemoneites), from the order Aglaspidida to erect a new order, Strabopida, this time suggesting a number of no more than two pairs of appendages. However, this new clade remained under the similarly-named Aglaspida subclass.[8] A year later, the British paleontologists Jason Andrew Dunlop and Paul Antony Selden eliminated Strabopida from the suborder Aglaspidida and classified them as the sister taxa of the latter based on the lack of aglaspidid apomorphies (distinctive characteristics), such as the lack of genal spines (a spine placed in the posterolateral part of the prosoma).[10] The authors who support this change have reinforced this argument by the trapezoidal form of the telson of Paleomerus and Strabops, in contrast to the long styliform (pen-shaped) telson of the aglaspidids.[9]

In 2004, the paleontologists O. Erik Tetlie and Rachel A. Moore described a fourth specimen of P. hamiltoni from the Mickwitzia Sandstone, PMO 201.957, housed at the Paleontologisk Museum, Oslo. Thanks to this new specimen, it was possible to confirm that Paleomerus did not possess twelve segments, but eleven, eliminating all the differences between Strabopidae and Paleomeridae (and therefore, making Paleomeridae redundant). It was also possible to notice an extra difference of Paleomerus and Strabops, the dimensions of the telson, being shorter and wider in the first than in the last one. Finally, Tetlie and Moore conclude that the phylogenetic position of the strabopids will be difficult to determine without further material that preserves the ventral morphology.[9] Subsequent authors have preferred to omit the strabopids from their analyses due to the poor abundance and preservation of their fossils, although the most accepted classification at the moment is of arthropods closely related to the Aglaspidida order, but not within it.[12]

Classification

Paleomerus is classified in the order Strabopida, in the clade Arachnomorpha, along with Strabops, Parapaleomerus and potentially Khankaspis.[13] It was described originally in 1956 as an intermediate form between xiphosurans (commonly known as horseshoe crabs) and eurypterids.[1] It would not be until 1997 when the order Strabopida was described,[8] but there is still doubt if the exclusion of them from Aglaspidida was really correct. The current status of the strabopids is of aglaspid-like arthropods of uncertain affinities.[12]

Paleomerus shares with the other strabopids a series of characteristics that distinguish them from all the other arthropods. These are an abdomen divided into eleven segments followed by a thick spine (the telson), a short head with sessile compound eyes and a rounded back. Like Strabops, Paleomerus possessed prominent dorsal eyes, however, there is no evidence of this in the fossils of Parapaleomerus.[8][13]

The great similarity that Strabops and Paleomerus share has cast doubt on many authors about whether both genera are really synonymous or not. Størmer described Paleomerus as an intermediate form between Xiphosura and Eurypterida, only highlighting a unique feature different from Strabops, a twelfth segment.[1] Nevertheless, a fourth specimen of the type species found in Sweden has shown that this extra segment actually represented the telson of the animal,[9] making them virtually indistinguishable.[10] Although this should convert both genera into synonyms, over time more differences have been highlighted, which are the position of the eyes (closer to each other and farther from the margin in Strabops than in Paleomerus)[7] and the size of the telson (longer and narrower in Strabops than in Paleomerus), which keep them as separate but closely related genera.[9]

The cladogram below published by Jason A. Dunlop and Paul A. Selden (1998) is based on the major chelicerate groups (in bold, Aglaspida, Eurypterida and Xiphosurida, Scorpiones and other arachnid clades) and their outgroup taxa (used as a reference group). Strabops and Paleomerus are shown as the sister taxa of Aglaspida.[10]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Note that there are several outdated elements. For example, Lemoneites was remitted to the Glyptocystitida order of echinoderms in 2005.[13]

Paleoecology

Paleomerus fossils have been discovered in Lower Cambrian deposits of Sweden and Poland.[2] The lanceolate body of Paleomerus could have facilitated rapid movements in the water, while the great flexibility of the abdomen would have allowed great agility and ability to spin in any direction. All this suggests that Paleomerus was an able swimmer who could even have rolled up itself on the sandy bottom of the sea as a method of protection. Due to the lack of knowledge of the ventral area, it is difficult to determine anything else about the paleoecology of Paleomerus.[1]

In the Mickwitzia Sandstone, where the specimens of P. hamiltoni were found, fossils of several other organisms have been found, such as the brachiopods Mickwitzia monilifera and M. pretiosa, the problematic indeterminate animal Torellella laevigata or the salterellid Volborthella tenuis.[14] These and other fossils, as well as the occurrence of green mineral grains (probably glauconite), indicate that P. hamiltoni lived in a well ventilated marine environment.[1] In addition, P. makowskii has been associated in the Ociesęki Sandstone Formation with the trilobites Holmia kjerulf, Kjerulfia orcina, Schmidtiellus panowi and Ellipsocephalus sanctacrucensis, alongside various indeterminate species of gasteropods, brachiopods and hyoliths.[15]

References

- Størmer, Leif (1956). "A Lower Cambrian merostome from Sweden" (PDF). Arkiv för Zoologi, Serie 2. 9: 507–514.

- Orłowski, Stanisław (1983). "A Lower Cambrian aglaspid from Poland". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte. 4: 237–241. ISSN 0028-3630. OCLC 1759692.

- Briggs, Derek E. G.; Mount, Jack D. (1982). "The Occurrence of the Giant Arthropod Anomalocaris in the Lower Cambrian of Southern California, and the Overall Distribution of the Genus". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (5): 1112–1118. JSTOR 1304568.

- Beecher, C. E. (1901). "Discovery of Eurypterid remains in the Cambrian of Missouri". American Journal of Science. 12 (71): 364–366. Bibcode:1901AmJS...12..364B. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-12.71.364.

- Xianguag, Hou; Siveter, David J.; Siveter, Derek J.; Aldridge, Richard J.; Pei-Yun, Cong; Gabbott, Sarah E.; Xiao-Ya, Ma; Purnell, Mark A.; Williams, Mark (2017). The Cambrian Fossils of Chengjiang, China: The Flowering of Early Animal Life (2 ed.). p. 328. ISBN 9781118896310.

- Størmer, Leif (1955). "Merostomata". Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part P Arthropoda 2, Chelicerata. p. 23.

- Bergström, Jan (1971). "Paleomerus – merostome or merostomoid". Lethaia. 4 (4): 393–401. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1971.tb01862.x.

- Hou, Xian-Guang; Bergström, Jan (1997). Arthropods of the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna, southwest China. Fossils and Strata. 45. pp. 1–116. ISBN 9788200376934.

- O. Erik Tetlie, Rachel A. Moore (2004). "A new specimen of Paleomerus hamiltoni (Arthropoda; Arachnomorpha)". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. 94 (3): 195–198. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.717.1248. doi:10.1017/S0263593300000602.

- Dunlop, J. A.; Selden, Paul A. (1998). The early history and phylogeny of the chelicerates. Arthropod Relationships. The Systematics Association Special Volume Series. 55. pp. 221–235. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-4904-4_17. ISBN 978-94-010-6057-8.

- Briggs, Derek Ernest Gilmor; Bruton, David L.; Whittington, Harry Blackmore (1979). "Appendages of the arthropod Aglaspis spinifer (Upper Cambrian, Wisconsin) and their significance" (PDF). Palaeontology. 22: 167–180.

- Ortega-Hernández, J.; Legg, D. A.; Braddy, S. J (2013). "The phylogeny of aglaspidid arthropods and the internal relationships within Artiopoda". Cladistics. 29: 15–45. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00413.x.

- Rudy Lerosey-Aubril (2014). "Notchia weugi gen. et sp. nov.: A new short-headed arthropod from the Weeks Formation Konservat-Lagerstatte (Cambrian; Utah)". Geological Magazine. 152 (2): 351–357. doi:10.1017/S0016756814000375.

- "Hjalmsater-Trolmen, Mickwitzia S. stone, Sweden - Jensen and Soren 1990: Atdabanian, Sweden". The Paleobiology Database.

- "Ocieseki Sandstone Formation - Orlowski 1985: Atdabanian, Poland". The Paleobiology Database.