Paenungulata

Paenungulata (from Latin paene “almost” + ungulātus “having hoofs") is a clade of "sub-ungulates", which groups three extant mammal orders: Proboscidea (including elephants), Sirenia (sea cows, including dugongs and manatees), and Hyracoidea (hyraxes). At least two more possible orders are known only as fossils, namely Embrithopoda and Desmostylia.[lower-alpha 1]

| Paenungulata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Elephants are the largest land mammals | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Superorder: | Afrotheria |

| Clade: | Paenungulata |

| Subgroups | |

Molecular evidence indicates that Paenungulata (or at least its extant members) is part of the cohort Afrotheria, an ancient assemblage of mainly African mammals of great diversity. The other members of this cohort are the orders Afrosoricida (tenrecs and golden moles), Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) and Tubulidentata (aardvarks).[5]

Of the five orders, hyraxes are the most basal, followed by embrithopods; the remaining orders (sirenians, desmostylians, and elephants) are more closely interrelated. These latter three are grouped as the Tethytheria, because it is believed that their common ancestors lived on the shores of the prehistoric Tethys Sea; however, recent myoglobin studies indicate that even Hyracoidea had an aquatic ancestor.[6]

History

In 1945, George Gaylord Simpson used traditional taxonomic techniques to group these spectacularly diverse mammals in the superorder he named Paenungulata ("almost ungulates"), but there were many loose threads in unravelling their genealogy.[7] For example, hyraxes in his Paenungulata had some characteristics suggesting they might be connected to the Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates, such as horses and rhinos). Indeed, early taxonomists placed the Hyracoidea closest to the rhinoceroses because of their dentition.

When genetic techniques were developed for inspecting amino acid differences among haemoglobin sequences the most parsimonious cladograms depicted Simpson's Paenungulata as an authentic clade and as one of the first groups to diversify from the basal placental mammals (Eutheria). The amino acid sequences reject a connection between extant paenungulates and perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates).[7]

However, a 2014 cladistic analysis placed anthracobunids and desmostylians, two major extinct groups that have been considered to be non-African afrotheres, close to each other within Perissodactyla.[4]

Phylogeny

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A cladogram of Afrotheria based on molecular evidence[8] |

Gallery

The rodent-like hyrax

The rodent-like hyrax A bull bush elephant

A bull bush elephant A manatee and her calf

A manatee and her calf Ocepeia, a basal species

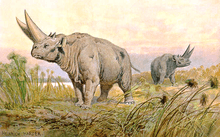

Ocepeia, a basal species The rhino-like embrithopods

The rhino-like embrithopods The desmostylians are the only extinct order of marine mammals. They might not be paenungulates.

The desmostylians are the only extinct order of marine mammals. They might not be paenungulates.

Extinct orders

Each of the extinct orders, the Embrithopoda and Desmostylia,[lower-alpha 1] was as unique in its members' ways of making a living as the three orders that survive. Embrithopods were rhinoceros-like herbivorous mammals with plantigrade feet, and desmostylians were hippopotamus-like amphibious animals. Their walking posture and diet have been the subject of speculation, but tooth wear indicates that desmostylians browsed on terrestrial plants and had a posture similar to other large hoofed mammals.[5]

See also

Notes

- Desmostylians, however, have been placed in Perissodactyla by a 2014 cladistic analysis,[4] and the taxonomic placement of embrithopods has also been questioned[2] though recently supported.[3]

References

- Gheerbrant, Emmanuel; Filippo, Andrea; Schmitt, Arnaud (2016). "Convergence of Afrotherian and Laurasiatherian Ungulate-Like Mammals: First Morphological Evidence from the Paleocene of Morocco". PLoS ONE. 11 (7): e0157556. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157556. PMC 4934866. PMID 27384169.

- Erdal, O.; Antoine, P.-O.; Sen, S.; Smith, A. (2016). "New material of Palaeoamasia kansui (Embrithopoda, Mammalia) from the Eocene of Turkey and a phylogenetic analysis of Embrithopoda at the species level" (PDF). Palaeontology. 59 (5): 631–655. doi:10.1111/pala.12247.

- E. Gheerbrant, A. Schmitt, & L. Kocsis (2018). "Early African fossils elucidate the origin of embrithopod mammals". Current Biology. 28: 2167. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.032.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cooper, L. N.; Seiffert, E.R.; Clementz, M.; Madar, S.I.; Bajpai, S.; Hussain, S.T.; Thewissen, J.G.M. (2014). "Anthracobunids from the Middle Eocene of India and Pakistan Are Stem Perissodactyls". PLoS ONE. 9 (10): e109232. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109232. PMC 4189980. PMID 25295875.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kleinschmidt, Traute; Czelusniak, John; Goodman, Morris; Braunitzer, Gerhard (1986). "Paenungulata: A comparison of the hemoglobin sequences from Elephant, Hyrax, and Manatee" (PDF). Mol. Biol. Evol. 3 (5): 427–435. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040411. PMID 3444412. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- "One Protein Shows Elephants and Moles Had Aquatic Ancestors". National Geographic Society. 13 June 2013.

- Seiffert, Erik; Guillon, J.M. (2007). "A new estimate of Afrotherian phylogeny based on simultaneous analysis of genomic, morphological, and fossil evidence" (PDF). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-224. PMC 2248600. PMID 17999766.

- Tabuce, R.; Asher, R. J.; Lehmann, T. (2008). "Afrotherian mammals: a review of current data" (PDF). Mammalia. 72: 2–14. doi:10.1515/MAMM.2008.004.

Sources

- Kleinschmidt, Traute; Czelusniak, John; Goodman, Morris; Braunitzer, Gerhard (1986). "Paenungulata: A comparison of the hemoglobin sequences from elephant, hyrax, and manatee" (PDF). Mol. Biol. Evol. 3 (5): 427–435. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040411. PMID 3444412. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- McKenna, M.C.; Bell, S.K., eds. (1997). Classification of Mammals above the Species Level. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11013-8.

- Seiffert, Erik; Guillon, J.M. (2007). "A new estimate of afrotherian phylogeny based on simultaneous analysis of genomic, morphological, and fossil evidence" (PDF). BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-224. PMC 2248600. PMID 17999766.

- Simpson, G.G. (1945). "The principles of classification and a classification of mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 85: 1–350.

Further reading

- Gheerbrant, E. (2005). "Paenungulata (Sirenia, Proboscidea, Hyracoidea, and Relatives)". In Rose, Kenneth D.; Archibald, J. David (eds.). The Rise of Placental Mammals: Origins and relationships of the major extant clades. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 84–105. ISBN 080188022X – via Google Books.

External links

- "Vertebrates: Paenungulata". Paleos.com.