Pac-Man

Pac-Man[lower-alpha 1] is a maze arcade game developed and released by Namco in 1980. The original Japanese title of Puck Man was changed to Pac-Man for international releases as a preventative measure against defacement of the arcade machines by changing the P to an F.[2] Outside Japan, the game was published by Midway Games as part of its licensing agreement with Namco America. The player controls Pac-Man, who must eat all the dots inside an enclosed maze while avoiding four colored ghosts. Eating large flashing dots called "energizers" causes the ghosts to turn blue, allowing Pac-Man to eat them for bonus points.

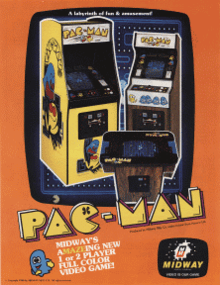

| Pac-Man | |

|---|---|

North American sales flyer | |

| Developer(s) | Namco |

| Publisher(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Toru Iwatani Shigeichi Ishimura |

| Programmer(s) | Shigeo Funaki |

| Composer(s) | Shigeichi Ishimura Toshio Kai |

| Series | Pac-Man |

| Platform(s) |

|

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Maze |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer (alternating turns) |

| Cabinet | Upright, cabaret, tabletop |

| Arcade system | Namco Pac-Man |

| CPU | 1 × Z80 @ 3.072 MHz[1] |

The development of the game began in early 1979, directed by Toru Iwatani with a nine-man team. Iwatani wanted to create a game that could appeal to women as well as men, because most video games of the time had themes of war or sports. Although the inspiration for the Pac-Man character was, reportedly, the image of a pizza with a slice removed, Iwatani has said he also rounded out the Japanese character for mouth, kuchi (Japanese: 口). The in-game characters were made to be cute and colorful to appeal to younger players. The original Japanese title of Puckman was derived from the titular character's hockey-puck shape.

Pac-Man was a widespread critical and commercial success, and it has an enduring commercial and cultural legacy. The game is considered important and influential, and it is commonly listed as one of the greatest video games of all time. The success of the game led to several sequels, merchandise, and two television series, as well as a hit single by Buckner and Garcia. The Pac-Man video game franchise remains one of the highest-grossing and best-selling game series of all time, generating more than $14 billion in revenue (as of 2016) and $43 million in sales combined. The character of Pac-Man is the mascot and flagship icon of Bandai Namco Entertainment and has the highest brand awareness of any video game character in North America.

Gameplay

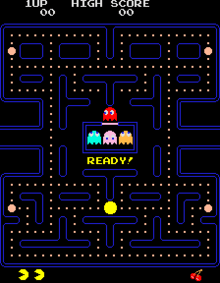

Pac-Man is a maze chase video game; the player controls the eponymous character through an enclosed maze. The objective of the game is to eat all of the dots placed in the maze while avoiding four colored ghosts — Blinky (red), Pinky (pink), Inky (cyan), and Clyde (orange) — that pursue him. When all of the dots are eaten, the player advances to the next level. If Pac-Man makes contact with a ghost, he will lose a life; the game ends when all lives are lost. Each of the four ghosts have their own unique, distinct artificial intelligence (A.I.), or "personalities"; Blinky gives direct chase to Pac-Man, Pinky and Inky try to position themselves in front of Pac-Man, usually by cornering him, and Clyde will switch between chasing Pac-Man and fleeing from him.[3][4][4]

Placed at the four corners of the maze are large flashing "energizers", or "power pellets". Eating these will cause the ghosts to turn blue with a dizzied expression and reverse direction. Pac-Man can eat blue ghosts for bonus points; when eaten, their eyes make their way back to the center box in the maze, where the ghosts are "regenerated" and resume their normal activity. Eating multiple blue ghosts in succession increases their point value. After a certain amount of time, blue-colored ghosts will flash white before turning back into their normal, lethal form. Eating a certain number of dots in a level will cause a bonus item, usually in the form of a fruit, to appear underneath the center box, which can be eaten for bonus points.

The game increases in difficulty as the player progresses; the ghosts become faster and the energizers' effect decreases in duration, to the point where the ghosts will no longer turn blue and edible. To the sides of the maze are two "warp tunnels", which allow Pac-Man and the ghosts to travel to the opposite side of the screen. Ghosts become slower when entering and exiting these tunnels. Levels are indicated by the fruit icon at the bottom of the screen. In-between levels are short cutscenes featuring Pac-Man and Blinky in humorous, comical situations. The game becomes unplayable at the 256th level due to an integer overflow that affects the game's memory.[5]

Development

After acquiring the struggling Japanese division of Atari in 1974, video game developer Namco began producing its own video games in-house, as opposed to simply licensing them from other developers and distributing them in Japan.[6][7] Company president Masaya Nakamura created a small video game development group within the company and ordered them to study several NEC-produced microcomputers to potentially create new games with.[8][9] One of the first people assigned to this division was a young 24-year-old employee named Toru Iwatani.[10] He created Namco's first video game Gee Bee in 1978, which while unsuccessful helped the company gain a stronger foothold in the quickly-growing video game industry.[11][12] He also assisted in the production of two sequels, Bomb Bee and Cutie Q, both released in 1979.[13][14]

The Japanese video game industry had surged in popularity with games such as Space Invaders and Breakout, which lead to the market being flooded with similar titles from other manufacturers in an attempt to cash in on the success.[15][16] Iwatani felt that arcade games only appealed to men for their crude graphics and violence,[15] and that arcades in general were seen as seedy environments.[17] For his next project, Iwatani chose to create a non-violent, cheerful video game that appealed mostly to women,[18] as he believed that attracting women and couples into arcades would potentially make them appear to be much-more family friendly in tone.[15] Iwatani began thinking of things that women liked to do in their time; he decided to center his game around eating, basing this on women liking to eat desserts and other sweets.[19] His game was initially called Pakkuman, based on the Japanese onomatopoeia term “paku paku taberu”,[20] referencing the mouth movement of opening and closing in succession.[18]

The game that later became Pac-Man began development in early 1979 and took a year and five months to complete, the longest ever for a video game up to that point.[21] Iwatani enlisted the help of nine other Namco employees to assist in production, including composer Toshio Kai, programmer Shigeo Funaki, and designer Shigeichi Ishimura.[22] Care was taken to make the game appeal to a “non-violent” audience, particularly women, with its usage of simple gameplay and cute, attractive character designs.[21][17] When the game was being developed, Namco was underway with designing Galaxian, which utilized a then-revolutionary RGB color display, allowing sprites to use several colors at once instead of utilizing colored strips of cellophane that was commonplace at the time;[21] this technological accomplishment allowed Iwatani to greatly enhance his game with bright pastel colors, which he felt would help attract players.[21] The idea for energizers was a concept Iwatani borrowed from Popeye the Sailor, a cartoon character that temporarily acquires superhuman strength after eating a can of spinach;[19] it is also believed that Iwatani was also partly inspired by a Japanese children's story about a creature that protected children from monsters by devouring them.[21]

Iwatani has often claimed that the character of Pac-Man himself was designed after the shape of a pizza with a missing slice while he was at lunch; in a 1986 interview he said that this was only half-truth,[10] and that the Pac-Man character was also based on him rounding out and simplifying the Japanese character “kuchi” (口), meaning “mouth”.[23][10] The four ghosts were made to be cute, colorful and appealing, utilizing bright, pastel colors and expressive blue eyes.[21] Iwatani had used this idea before in Cutie Q, which features similar ghost-like characters, and decided to incorporate it into Pac-Man.[15] He was also inspired by the television series Casper the Friendly Ghost and the manga Obake no Q-Taro.[19] Ghosts were chosen as the game's main antagonists due to them being used as villainous characters in animation.[19]

Originally, Namco president Masaya Nakamura had requested that all of the ghosts be red and thus indistinguishable from one another.[24] Iwatani believed that the ghosts should be different colors, and he received unanimous support from his colleagues for this idea.[24] Each of the ghosts were programmed to have their own distinct personalities, so as to keep the game from becoming too boring or impossibly difficult to play.[21][25] Each ghost's name gives a hint to its strategy for tracking down Pac-Man: Shadow ("Blinky") always chases Pac-Man, Speedy ("Pinky") tries to get ahead of him, Bashful ("Inky") uses a more complicated strategy to zero in on him, and Pokey ("Clyde") alternates between chasing him and running away.[21] (The ghosts' Japanese names, translated into English, are Chaser, Ambusher, Fickle, and Stupid, respectively.) To break up the tension of constantly being pursued, humorous intermissions between Pac-Man and Blinky were added.[16] The sound effects were among the last things added to the game,[21] created by Toshio Kai.[17] In a design session, Iwatani noisily ate fruit and made gurgling noises to describe to Kai how he wanted the eating effect to sound.[17] Upon completion, the game was titled Puck Man, based on the working title and the titular character's distinct hockey puck-like shape.[7]

Release

Location testing for Puck Man began on May 22, 1980 in Shibuya, Tokyo, to a relatively positive fanfare from players.[19] A private showing for the game was done in June, followed by a nation-wide release in July.[7] Eyeing the game's success in Japan, Namco initialized plans to bring the game to international countries, particularly the United States.[21] Before showing the game to distributors, Namco America made a number of changes, such as altering the names of the ghosts.[21] The biggest of these was the game's title; executives at Namco were worried that vandals would change the “P” in Puck Man to an “F”, forming an obscene name.[7][26] Masaya Nakamura chose to rename it to Pac-Man, as he felt it was closer to the game's original Japanese title of Pakkuman.[7] When Namco presented Pac-Man and Rally-X to potential distributors at the 1980 AMOU tradeshow in November,[27] executives believed that Rally-X would be the best-selling game of that year.[7][28] Midway Games agreed to distribute both games in North America, announcing their acquisition of the manufacturing rights on November 22[29] and releasing them in December.[30]

Conversions

Pac-Man was ported to a plethora of home video game systems and personal computers; the most infamous of these is the 1982 Atari 2600 conversion, designed by Tod Frye and published by Atari.[31] This version of the game was widely criticized for its inaccurate portrayal of the arcade version and for its peculiar design choices, most notably the flickering effect of the ghosts.[32][33][34] Although the game proved to be a success initially, Atari overestimated the game's demand and produced 12 million cartridges, selling seven million and leaving five million unsold.[35][36][37][38] The conversion's poor quality severely damaged the company's reputation and contributed to the company's demise and the North American video game crash of 1983.[35][39] Atari also released versions for the Intellivision, Commodore VIC-20, Commodore 64, Apple II, IBM PC, Texas Instruments TI-99/4A, ZX Spectrum, and the Atari 8-bit family of computers. A port for the Atari 5200 was released in 1983, a version that many have seen as a significant improvement over the Atari 2600 version.[40]

Namco themselves released a version for the Family Computer in 1984 as one of the console's first third-party titles,[41] as well as a port for the MSX computer.[42] The Famicom version was later released in North America for the Nintendo Entertainment System by Tengen, a subsidiary of Atari Games. Tengen also produced an unlicensed version of the game in a black cartridge shell, released during a time where Tengen and Nintendo were in bitter disagreements over the latter's stance on quality control for their consoles; this version was later re-released by Namco as an official title in 1993, featuring a new cartridge label and box. The Famicom version was released for the Famicom Disk System in 1990 as a budget title for the Disk Writer kiosks in retail stores.[41] The same year, Namco released a port of Pac-Man for the Game Boy, which allowed for two-player co-operative play via the Game Link Cable peripheral. A version for the Game Gear was released a year later, which also enabled support for multiplayer. In celebration of the game's 20th anniversary in 1999, Namco re-released the Game Boy version for the Game Boy Color, bundled with Pac-Attack and titled Pac-Man: Special Color Edition.[43] The same year, Namco and SNK co-published a port for the Neo Geo Pocket Color, which came with a circular "Cross Ring" that attached to the d-pad to restrict it to four-directional movement.[44]

In 2001, Namco released a port of Pac-Man for various Japanese mobile phones, being one of the company's very first mobile game releases.[45] The Famicom version of the game was re-released for the Game Boy Advance in 2004 as part of the Famicom Mini series, released to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Famicom; this version was also released in North America and Europe under the Classic NES Series label.[46] Namco Networks released Pac-Man for BREW mobile devices in 2005.[47] The arcade original was released for the Xbox Live Arcade service in 2006, featuring achievements and online leaderboards. In 2009 a version for iOS devices was published; this release was later rebranded as Pac-Man + Tournaments in 2013, featuring new mazes and leaderboards. The NES version was released for the Wii Virtual Console in 2007. A Roku version was released in 2011,[48] alongside a port of the Game Boy release for the 3DS Virtual Console. Pac-Man was one of four titles released under the Arcade Game Series brand, which was published for the Xbox One, PlayStation 4 and PC in 2016.[49]

Pac-Man is included in many Namco compilations, including Namco Museum Vol. 1 (1995),[50] Namco Museum 64 (1999),[51] Namco Museum Battle Collection (2005),[52] Namco Museum DS (2007), Namco Museum Essentials (2009),[53] and Namco Museum Megamix (2010).[54] In 1996, it was re-released for arcades as part of Namco Classic Collection Vol. 2, alongside Dig Dug, Rally-X and special "Arrangement" remakes of all three titles.[55][56] Microsoft included Pac-Man in Microsoft Return of Arcade (1995) as a way to help attract video game companies to their Windows 95 operating system.[57] Namco released the game in the third volume of Namco History in Japan in 1998.[58] The 2001 Game Boy Advance compilation Pac-Man Collection compiles Pac-Man, Pac-Mania, Pac-Attack and Pac-Man Arrangement onto one cartridge.[59] Pac-Man is also a hidden extra in the arcade game Ms. Pac-Man/Galaga - Class of 1981 (2001).[60][61] A similar cabinet was released in 2005 that featured Pac-Man as the centerpiece.[62] Pac-Man 2: The New Adventures (1993) and Pac-Man World 2 (2002) have Pac-Man as an unlockable extra. Alongside the Xbox 360 remake Pac-Man Championship Edition, it was ported to the Nintendo 3DS in 2012 as part of Pac-Man & Galaga Dimensions.[63] The 2010 Wii game Pac-Man Party and its 2011 3DS remake also include Pac-Man as a bonus game, alongside the arcade versions of Dig Dug and Galaga.[64][65] In 2014, Pac-Man was included in the compilation title Pac-Man Museum for the Xbox 360, PlayStation 3 and PC, alongside several other Pac-Man games.[66] The NES version is one of 30 games included in the NES Classic Edition.[67]

Reception

Sales

When it was first released in Japan, Pac-Man was only a modest success; Namco's own Galaxian had quickly outdone the game in popularity, due to the predominately male playerbase being familiar with its shooting gameplay as opposed to Pac-Man's cute characters and maze-chase theme.[21] Iwatani claims that the game was very popular with women, which he had hoped to accomplish during development. By comparison, in North America, Pac-Man became a nation-wide success. Within one year, more than 100,000 arcade units had been sold which grossed more than US$1 billion in quarters.[68][69] Pac-Man overtook Asteroids as the best-selling arcade game in the country,[70] and surpassed Star Wars: A New Hope with more than US$1 billion in revenue.[71][72] By 1982, it was estimated to have had 30 million active players across the United States.[73] Some arcades purchased entire rows of Pac-Man cabinets.[7]

The number of arcade units sold had tripled to 400,000 by 1982, receiving an estimated total of seven billion coins.[74] Pac-Man themed merchandise sales had also exceeded US$1 billion.[74] In a 1983 interview, Nakamura said that though he did expect Pac-Man to be successful, "I never thought it would be this big."[6] Pac-Man is the best-selling arcade game of all time with more than US$2.5 billion in revenue, surpassing Space Invaders[69][75] — in 2016, USgamer calculated that the machines' inflation-adjusted takings were equivalent to $7.68 billion.[76] The Atari 2600 version of the game sold over seven million copies, making it the console's best-selling title.[77] The Family Computer version and its 2004 Game Boy advance re-release sold a combined 598,000 copies in Japan.[78][79] Coleco's tabletop arcade unit sold over 1.5 million units,[80] while mobile phone ports have sold over 30 million paid downloads.[81] In total, Pac-Man re-releases have sold a combined total of 39,098,000 million copies, making it the tenth best-selling video game of all time.

Reviews

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Pac-Man was awarded "Best Commercial Arcade Game" at the 1982 Arcade Awards.[89] II Computing listed the Atarisoft port tenth on the magazine's list of top Apple II games as of late 1985, based on sales and market-share data.[90] In 2001, Pac-Man was voted the greatest video game of all time by a Dixons poll in the UK.[91] The list aggregator site Playthatgame currently ranks Pac-Man as the #53rd top game of all-time & game of the year.[92]

Impact

The game of Pac-Man is considered by many to be one of the most influential video games of all time;[93][94][95] its title character was the first original gaming mascot, the game established the maze chase game genre, it demonstrated the potential of characters in video games, it increased the appeal of video games with female audiences, and it was gaming's first broad licensing success.[93] It was the first video game with power-ups,[96] and the individual ghosts have deterministic artificial intelligence (AI) that reacts to player actions.[97] It is often cited as the first game with cutscenes (in the form of brief comical interludes about Pac-Man and Blinky chasing each other),[98]:2 though actually Space Invaders Part II employed a similar style of between-level intermissions in 1979.[99]

"Maze chase" games exploded on home computers after the release of Pac-Man. Some of them appeared before official ports and garnered more attention from consumers, and sometimes lawyers, as a result. These include Taxman (1981) and Snack Attack (1982) for the Apple II, Jawbreaker (1981) for the Atari 8-bit family, Scarfman (1981) for the TRS-80, and K.C. Munchkin! (1981) for the Odyssey². Namco themselves produced several other maze chase games, including Rally-X (1980), Dig Dug (1982), Exvania (1992), and Tinkle Pit (1994).

Pac-Man also inspired 3D variants of the concept, such as Monster Maze (1982),[100] Spectre (1982), and early first-person shooters such as MIDI Maze (1987; which also had similar character designs).[98]:5[101] John Romero credited Pac-Man as the game that had the biggest influence on his career;[102] Wolfenstein 3D includes a Pac-Man level from a first-person perspective.[103][104] Many post-Pac-Man titles include power-ups that briefly turn the tables on the enemy. The game's artificial intelligence inspired programmers who later worked for companies like Bethesda.[97]

Legacy

.jpg)

Guinness World Records has awarded the Pac-Man series eight records in Guinness World Records: Gamer's Edition 2008, including "Most Successful Coin-Operated Game". On June 3, 2010, at the NLGD Festival of Games, the game's creator Toru Iwatani officially received the certificate from Guinness World Records for Pac-Man having had the most "coin-operated arcade machines" installed worldwide: 293,822. The record was set and recognized in 2005 and mentioned in the Guinness World Records: Gamer's Edition 2008, but finally actually awarded in 2010.[105]

The Pac-Man character and game series became an icon of video game culture during the 1980s. A wide variety of Pac-Man merchandise has been marketed with the character's image, including t-shirts, toys, hand-held video game imitations, pasta, and cereal.

The game has inspired various real-life recreations, involving real people or robots. One event called Pac-Manhattan set a Guinness World Record for "Largest Pac-Man Game" in 2004.[106][107][108] The business term "Pac-Man defense" in mergers and acquisitions refers to a hostile takeover target that attempts to reverse the situation and instead acquire its attempted acquirer, a reference to Pac-Man's energizers.[109] The game's popularity has led to "Pac-Man" being adopted as a nickname, such as by boxer Manny Pacquiao[110] and the American football player Adam Jones. The "Pac-Man renormalization" is named for a cosmetic resemblance to the character, in the mathematical study of the Mandelbrot set.[111][112]

On August 21, 2016, in the 2016 Summer Olympics closing ceremony, during a video which showcases Tokyo as the host of the 2020 Summer Olympics, a small segment shows Pac-Man and the ghosts racing and eating dots on a running track.[113]

Television

The Pac-Man animated TV series produced by Hanna–Barbera aired on ABC from 1982 to 1983.[114] A computer-generated animated series titled Pac-Man and the Ghostly Adventures aired on Disney XD in June 2013.[115][116] As of February 2019, the series was also planned to air on Universal Kids, but it was ultimately canceled due to low coverage of NBCUniversal.

Music

The Buckner & Garcia song "Pac-Man Fever" (1981) went to No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100 charts,[117] and received a Gold certification for more than 1 million records sold by 1982,[118] and a total of 2.5 million copies sold as of 2008.[119] More than one million copies of the group's Pac-Man Fever album (1982) were sold.[120]

In 1982, "Weird Al" Yankovic recorded a parody of "Taxman" by the Beatles as "Pac-Man". It was eventually released in 2017 as part of Squeeze Box: The Complete Works of "Weird Al" Yankovic.[121][122] In 1992, Aphex Twin (with the name Power-Pill) released Pac-Man, a techno album which consists mostly of samples from the game.

On July 20th, 2020, Gorillaz and ScHoolboy Q, released a track entitled "PAC-MAN" as a part of Gorillaz' Song Machine series to commemorate the game's 40th anniversary, with the music video depicting the band's frontman, 2-D, playing a Gorillaz-themed Pac-Man game.[123]

Film

The Pac-Man character appears in the film Pixels (2015), with Denis Akiyama playing series creator Toru Iwatani.[124][125] Pac-Man is referenced and makes an appearance in the 2017 film Guardians of the Galaxy 2.[126] The game, the character, and the ghosts all also appear in the film Wreck-It Ralph,[127][128] as well as the sequel Ralph Breaks the Internet.

In Sword Art Online The Movie: Ordinal Scale where Kirito and his friends beat a virtual reality game called PAC-Man 2024.[129] Iwatani makes a cameo at the beginning of the film as an arcade technician. In the Japanese tokusatsu film Kamen Rider Heisei Generations: Dr. Pac-Man vs. Ex-Aid & Ghost with Legend Riders, a Pac-Man-like character is the main villain.[130]

The 2018 film Relaxer uses Pac-Man as a strong plot element in the story of a 1999 couch-bound man who attempts to beat the game (and encounters the famous Level 256 glitch) before the year 2000 problem occurs.[131]

In 2008, a feature film based on the game was in development.[132][133]

Other gaming media

In 1982, Milton Bradley released a board game based on Pac-Man.[134] Players move up to four Pac-Man characters (traditional yellow plus red, green, and blue) plus two ghosts as per the throws of a pair of dice. The two ghost pieces were randomly packed with one of four colors.[135]

Sticker manufacturer Fleer included rub-off game cards with its Pac-Man stickers. The card packages contain a Pac-Man style maze with all points along the path hidden with opaque coverings. From the starting position, the player moves around the maze while scratching off the coverings to score points.[136]

Pac-Man is a playable character in Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U. The 3DS version has a stage based on the original arcade game, called Pac-Maze.[137] Nintendo released an Amiibo figurine of Pac-Man. Pac-Man is a playable character in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate.

A Pac-Man-themed downloadable content package for Minecraft was released in 2020 in commemoration of the game's 40th anniversary. This pack introduced a new ghost called 'Creepy', based on the Creeper.[138]

Perfect scores and other records

A perfect score on the original Pac-Man arcade game is 3,333,360 points, achieved when the player obtains the maximum score on the first 255 levels by eating every dot, energizer, fruit and blue ghost without losing a man, then uses all six men to obtain the maximum possible number of points on level 256.[139][140]

The first person to achieve a publicly witnessed and verified perfect score without manipulating the game's hardware to freeze play was Billy Mitchell, who performed the feat on July 3, 1999.[140][141] Some recordkeeping organizations removed Mitchell's score after a 2018 investigation by Twin Galaxies concluded that two unrelated Donkey Kong score performances submitted by Mitchell had not used an unmodified original circuit board.[142] As of July 2020, seven other gamers had achieved perfect Pac-Man scores on original arcade hardware.[143] The world record for the fastest completion of a perfect score, according to Twin Galaxies, is currently held by David Race with a time of 3 hours, 28 minutes, 49 seconds.[144][145]

In December 1982, eight-year-old boy Jeffrey R. Yee received a letter from United States president Ronald Reagan congratulating him on a world record score of 6,131,940 points, possible only if he had passed level 256.[140] In September 1983, Walter Day, chief scorekeeper at Twin Galaxies at the time, took the U.S. National Video Game Team on a tour of the East Coast to visit gamers who claimed the ability to pass that level. None demonstrated such an ability. In 1999, Billy Mitchell offered $100,000 to anyone who could pass level 256 before January 1, 2000. The offer expired with the prize unclaimed.[140]

After announcing in 2018 that it would no longer recognize the first perfect score on Pac-Man, Guinness World Records reversed that decision and reinstated Billy Mitchell's 1999 performance on June 18, 2020.[146]

Remakes and sequels

Pac-Man inspired a long series of sequels, remakes, and re-imaginings, and is one of the longest-running video game franchises in history. The first of these was Ms. Pac-Man, developed by the American-based General Computer Corporation and published by Midway in 1982. The character's gender was changed to female in response to Pac-Man's popularity and women, with new mazes, moving bonus items, and faster gameplay being implemented to increase its appeal. Ms. Pac-Man is one of the best-selling arcade games in North America, and it is often seen as being superior to its predecessor. Legal concerns raised over who owned the game caused Ms. Pac-Man to become owned by Namco, who assisted in production of the game. Ms. Pac-Man inspired its own line of remakes, including Ms. Pac-Man Maze Madness (2000), and Ms. Pac-Man: Quest for the Golden Maze, and is also included in many Namco and Pac-Man collections for consoles.

Namco's own follow-up to the original was Super Pac-Man, released in 1982. This was followed by the Japan-exclusive Pac & Pal in 1983.[147] Midway produced many other Pac-Man sequels during the early 1980s, including Pac-Man Plus (1982), Jr. Pac-Man (1983), Baby Pac-Man (1983), and Professor Pac-Man (1984). Other games include the isometric Pac-Mania (1987), the side-scrollers Pac-Land (1984), Hello! Pac-Man (1994), and Pac-In-Time (1995),[148] the 3D platformer Pac-Man World (1999), and the puzzle games Pac-Attack (1991) and Pac-Pix (2005). Iwatani designed Pac-Land and Pac-Mania, both of which remain his favorite games in the series. Pac-Man Championship Edition, published for the Xbox 360 in 2007, was Iwatani's final game before leaving the company. Its neon visuals and fast-paced gameplay was met with acclaim,[149] leading to the creation of Pac-Man Championship Edition DX (2010) and Pac-Man Championship Edition 2 (2016).[150]

Coleco's tabletop Mini-Arcade versions of the game yielded 1.5 million units sold in 1982.[151][152] Nelsonic Industries produced a Pac-Man LCD wristwatch game with a simplified maze also in 1982.[153]

Namco Networks sold a downloadable Windows PC version of Pac-Man in 2009 which also includes an enhanced mode which replaces all of the original sprites with the sprites from Pac-Man Championship Edition. Namco Networks made a downloadable bundle which includes its PC version of Pac-Man and its port of Dig Dug called Namco All-Stars: Pac-Man and Dig Dug. In 2010, Namco Bandai announced the release of the game on Windows Phone 7 as an Xbox Live game.[154]

For the weekend of May 21–23, 2010, Google changed the logo on its homepage to a playable version of the game[155] in recognition of the 30th anniversary of the game's release. The Google Doodle version of Pac-Man was estimated to have been played by more than 1 billion people worldwide in 2010,[156] so Google later gave the game its own page.[157]

In April 2011, Soap Creative published World's Biggest Pac-Man, working together with Microsoft and Namco-Bandai to celebrate Pac-Man's 30th anniversary. It is a multiplayer browser-based game with user-created, interlocking mazes.[158]

Notes

References

- Nitsche, Michael (March 31, 2009). "Games and Rules". Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-262-14101-7.

[...] they would not realize the fundamental logical difference between a version of Pac-Man (Iwatani 1980) running on the original Z80 [...]

- "22 May 1980: Pac-Man hits the arcades". moneyweek.com. May 22, 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "News Headlines". Cnbc.com. March 3, 2011. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- CNBC.com, Chris Morris|Special to (March 3, 2011). "Five Things You Never Knew About Pac-Man". www.cnbc.com. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- Dwyer, James; Dwyer, Brendan (2014). Cult Fiction. Paused Books. p. 14. ISBN 9780992988401.

- Sobel, Jonathan (January 30, 2017). "Masaya Nakamura, Whose Company Created Pac-Man, Dies at 91". New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- Kent, Steven L. (2002). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. New York: Random House International. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7. OCLC 59416169. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016.

- Microcomputer BASIC Editorial Department (December 1986). All About Namco (in Japanese). Dempa Shimbun. ISBN 978-4885541070.

- Burnham, Van (2001). Supercade. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 181. ISBN 0-262-02492-6.

- Lammers, Susan M. (1986). Programmers at Work: Interviews. New York: Microsoft Press. p. 266. ISBN 0-914845-71-3.

- Kurokawa, Fumio (March 17, 2018). "ビデオゲームの語り部たち 第4部:石村繁一氏が語るナムコの歴史と創業者・中村雅哉氏の魅力". 4Gamer (in Japanese). Aetas. Archived from the original on August 1, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- Masumi, Akagi (2005). It Started With Pong. Amusement News Agency. pp. 183–184.

- "Bomb Bee - Videogame by Namco". Killer List of Videogames. The International Arcade Museum. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- "Cutie Q - Videogame by Namco". Killer List of Videogames. The International Arcade Museum. Archived from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Purchese, Robert (May 20, 2010). "Iwatani: Pac-Man was made for women". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 4, 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Iwatani, Toru (2005). Introduction to Pac-Man's Game Science. Enterbrain. p. 33.

- Peckham, Matt (May 22, 2015). "Pac-Man Creator Toru Iwatani on the Character's Past and Future". Time. Time Warner. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Kohler, Chris (2005). Power-Up: How Japanese Video Games Gave the World an Extra Life. BradyGames. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-7440-0424-1. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- Kohler, Chris (May 21, 2010). "Q&A: Pac-Man Creator Reflects on 30 Years of Dot-Eating". Wired. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- "Top 25 Smartest Moves in Gaming". Gamespy.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- Pittman, Jamey (February 23, 2009). "The Pac-Man Dossier". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on January 9, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Szczepaniak, John (August 11, 2014). The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers (First ed.). p. 201. ISBN 978-0992926007. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- Green, Chris (June 17, 2002). "Pac-Man". Salon.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2005. Retrieved February 12, 2006.

- England, Lucy (June 11, 2015). "When Pac-Man was invented there was a huge internal fight with the CEO over what colour the ghosts should be". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- Mateas, Michael (2003). "Expressive AI: Games and Artificial Intelligence" (PDF). Proceedings of Level Up: Digital Games Research Conference, Utrecht, Netherlands. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2012. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- Brian Ashcraft. "This Guy Has a Rare Arcade Cabinet. Is It Real?". Kotaku. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013.

- "Coin Machines" (PDF). Cashbox. November 15, 1980. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Atari Spectacularly Fails to Do the Math". Next Generation. No. 26. Imagine Media. February 1997. p. 47.

- "Midway Bows New 'Pac-Man' Video" (PDF). Cashbox. November 22, 1980. p. 42. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Game Board Schematic" (PDF). Midway Pac-Man Parts and Operating Manual. Chicago, Illinois: Midway Games. December 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- Lapetino, Tim (2018). "The Story of PAC-MAN on Atari 2600". Retro Gamer Magazine. 179: 18–23.

- "Creating a World of Clones". Philadelphia Inquirer. October 9, 1983. p. 16.

- Thompson, Adam (Fall 1983). "The King of Video Games is a Woman". Creative Computing Video and Arcade Games. 1 (2): 65. Archived from the original on July 6, 2009.

- Ratcliff, Matthew (August 1988). "Classic Cartridges II". Antic. 7 (4): 24. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010.

- Buchanan, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Ellis, David (2004). "The Atari VCS (2000)". Official Price Guide to Classic Video Games. Random House. pp. 98–99. ISBN 0-375-72038-3.

- Buchanan, Levi (November 26, 2008). "Top 10 Videogame Turkeys". IGN. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- Katz, Arnie; Kunkel, Bill (May 1982). "The A-Maze-ing World of Gobble Games" (PDF). Electronic Games. 1 (3): 62–63 [63]. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- Nicoll, Benjamin (2015). "Bridging the Gap: The Neo Geo, the Media Imaginary, and the Domestication of Arcade Games". Games and Culture. doi:10.1177/1555412015590048.

- Montfort, Nick; Bogost, Ian (2009). "Pac-Man". Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. pp. 66–79. ISBN 978-0-262-01257-7.

- Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography (2003). Family Computer 1983 - 1994. Japan: Otashuppan. ISBN 4872338030.

- "Dempa Micomsoft Super Soft Catalogue". Dempa. May 1984. p. 4. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Harris, Craig (September 3, 1999). "Pac-Man: Special Color Edition". IGN. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- Hannley, Steve (July 6, 2013). "Pocket Power: Pac-Man". Hardcore Gamer. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- Softbank (January 18, 2001). "「パックマン」「ギャラクシアン」が携帯電話に登場!". Soft Bank News. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- Harris, Craig (June 4, 2004). "Classic NES Series: Pac-Man". IGN. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- "Namco Networks' Pac-Man Franchise Surpasses 30 Million Paid Transactions in the United States on Brew". AllBusiness.com. 2010. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- Pierce, David (October 31, 2011). "Roku 2 gets new firmware, games; Pac-Man, Galaga, and more". The Verge. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Romano, Sal (December 21, 2015). "Bandai Namco bringing classic Arcade Game Series to PS4, Xbox One, and PC". Gematsu. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "Review Crew: Namco Arcade Classics". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 82. Sendai Publishing. May 1996. p. 34.

- Fielder, Joe (April 28, 2000). "Namco Museum 64 Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Parish, Jeremy (August 30, 2005). "Namco Museum Battle Collection". 1UP.com. IGN. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- Roper, Chris (July 21, 2009). "Namco Museum Essentials Review". IGN. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Buchanan, Levi (November 22, 2010). "Namco Museum Megamix Review". IGN. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- "Retroview - Namco Classic Collection 2" (33). Edge. May 1996. p. 79. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- Bobinator (August 18, 2019). "Pac-Man Arrangement". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- "Windows 95 Gets Into The Game" (20). IDG Communications. Electronic Entertainment. August 1995. p. 48. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "キャラクターモノ大特集の「NAMCO HISTORY VOL.3」6月発売". PC Watch (in Japanese). Impress Group. March 27, 1998. Archived from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- Latshaw, Tim (June 17, 2014). "Pac-Man Collection". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Harris, John (March 28, 2017). "Passing Through Ghosts in Pac-Man". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "Ms. Pac-Man/Galaga - Class of 1981 - Videogame by Namco". Killer List of Videogames. Archived from the original on June 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "Pac-Man 25th Anniversary - Videogame by Namco". Killer List of Videogames. Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Wahlgren, Jon (July 27, 2011). "Pac-Man & Galaga Dimensions Review (3DS)". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- IGN Staff (October 25, 2010). "Pac-Man Party has Gone Gold for Wii". IGN. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Miller, Zachary (December 2, 2011). "Pac-Man Party 3D Review". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- Cavalli, Earnest (January 30, 2014). "Pac-Man Museum arrives February 25, free Ms. Pac-Man DLC in tow". Engadget. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- Webster, Andrew (June 14, 2016). "Nintendo is releasing a miniature NES with 30 built-in games". The Verge. Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Bill Loguidice & Matt Barton (2009). Vintage games: an insider look at the history of Grand Theft Auto, Super Mario, and the most influential games of all time. Focal Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-240-81146-8. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

The machines were well worth the investment; in total they raked in over a billion dollars worth of quarters in the first year alone.

- Mark J. P. Wolf (2008). The video game explosion: a history from PONG to PlayStation and beyond. ABC-CLIO. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-313-33868-7. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

It would go on to become arguably the most famous video game of all time, with the arcade game alone taking in more than a billion dollars. One study estimated that it had been played more than 10 billion times during the twentieth century.

- Mark J. P. Wolf (2001). The medium of the video game. University of Texas Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-292-79150-X. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- Haddon, L. (1988). "Electronic and Computer Games: The History of an Interactive Medium". Screen. 29 (2): 52–73 [53]. doi:10.1093/screen/29.2.52. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

Revenue from the game Pac-Man alone was estimated to exceed that from the cinema box-office success Star Wars.

- Kevin "Fragmaster" Bowen (2001). "Game of the Week: Pac-Man". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- "Men's wear, Volume 185". Men's Wear. Fairchild Publications. 185. 1982. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- Kao, John J. (1989). Entrepreneurship, creativity & organization: text, cases & readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 45. ISBN 0-13-283011-6. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

Estimates counted 7 billion coins that by 1982 had been inserted into some 400,000 Pac Man machines worldwide, equal to one game of Pac Man for every person on earth. US domestic revenues from games and licensing of the Pac Man image for T-shirts, pop songs, to wastepaper baskets, etc. exceeded $1 billion.

- Chris Morris (May 10, 2005). "Pac Man turns 25: A pizza dinner yields a cultural phenomenon – and millions of dollars in quarters. He also loved to eat a lot of pellets". CNN. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

In the late 1990s, Twin Galaxies, which tracks video game world record scores, visited used game auctions and counted how many times the average Pac Man machine had been played. Based on those findings and the total number of machines that were manufactured, the organization said it believed the game had been played more than 10 billion times in the 20th century.

- "Top 10 Highest-Grossing Arcade Games of All Time". USgamer. January 1, 2016. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- Buchanan, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- "Game Search (based on Famitsu data)". Game Data Library. March 1, 2020. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Namco (Japan sales, 2000-2006)". Garaph (based on Famitsu data). July 28, 2005. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- "Coleco Mini-Arcades Go Gold" (PDF). Arcade Express. 1 (1): 4. August 15, 1982. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- "Namco Networks' PAC-MAN Franchise Surpasses 30 Million Paid Transactions in the United States on Brew". Business Wire. Berkshire Hathaway. June 30, 2010. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Alan Weiss, Brett (1998). "Pac-Man [Namco Arcade]". Allgame. Allmedia. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- Alan Weiss, Brett (1998). "Pac-Man [Tengen Unlicensed]". Allgame. Allmedia. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- "Atari - Pac-Man" (17). Computer & Video Games. March 1983. p. 7. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Pickering, Chris (October 31, 2007). "Pac-Man". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Harris, Craig (September 3, 1999). "Pac-Man - Neo Geo Pocket Color". IGN. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Matt; Julian (January 1991). "Pac-Man review - Nintendo Gameboy" (4). Mean Machines. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- Miller, David (July 5, 1984). "Power Pills". Popular Computing Weekly. p. 29. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- 1981 Arcade Awards – Electronic Games March 1982, pages 46–49.

- Ciraolo, Michael (October–November 1985). "Top Software: A List of Favorites". II Computing: 51. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- "Pac Man 'greatest video game'". BBC News. November 13, 2001. Archived from the original on December 18, 2006. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- Jeroen te Strake, Peter Searle. "Thebiglist". Playthatgame.co.uk. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- "The Essential 50 Part 10 -- Pac-Man from 1UP.com". 1Up.com. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- Wilson, Jeffrey L. (June 11, 2010). "The 10 Most Influential Video Games of All Time". PC Magazine. 1. Pac-Man (1980). Archived from the original on April 11, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- The ten most influential video games ever, The Times, September 20, 2007

- "Playing With Power: Great Ideas That Have Changed Gaming have from 1UP.com". 1Up.com. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- Consalvo, Mia (2016). Atari to Zelda: Japan's Videogames in Global Contexts. MIT Press. pp. 193–4. ISBN 978-0262034395.

- "Gaming's most important evolutions". GamesRadar+. October 8, 2010. Archived from the original on November 7, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "Space Invaders Part II". Arcade History.

- "Monster Maze".

- "25 years of Pac-Man". MeriStation. July 4, 2005. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved May 6, 2011. (Translation)

- Bailey, Kat (March 9, 2012). "These games inspired Cliff Bleszinski, John Romero, Will Wright, and Sid Meier". Joystiq. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- Book of Games: The Ultimate Reference on PC & Video Games. Book of Games. 2006. p. 24. ISBN 82-997378-0-X. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2011.

- "Game developer". 2 & 5. Miller Freeman. 1995: 62. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

If you made it to the secret Pac-Man level in Castle Wolfenstein, you know what I mean (Pac-Man never would have made it as a three-dimensional game). Though it may be less of a visual feast, two dimensions have a well-established place as an electronic gaming format.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Martijn Müller (June 3, 2010). "Pac-Man wereldrecord beklonken en het hele verhaal" (in Dutch). NG-Gamer. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- "About Pac-Manhattan". Pac-Manhattan. 2004. Archived from the original on May 8, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "Roomba Pac-Man Web Site". Archived from the original on November 9, 2009. Retrieved October 10, 2009.

- Lau, Dominic. "Pacman in Vancouver". SFU Computing Science. Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "Origins of the 'Pac-Man' Defense". The New York Times. January 23, 1988. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- Brunell, Evan (May 22, 2010). "Popular Video Game Pac-Man Celebrates 30th Anniversary". New England Sports Network. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- Selinger, Nikita; Lyubich, Mikhail; Dudko, Dzmitry (March 3, 2017). "Pacman renormalization and self-similarity of the Mandelbrot set near Siegel parameters". arXiv:1703.01206v2. Bibcode:2017arXiv170301206D. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lyubich, Mikhail; Dudko, Dzmitry (August 30, 2018). "Local connectivity of the Mandelbrot set at some satellite parameters of bounded type". arXiv:1808.10425v2. Bibcode:2018arXiv180810425D. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Mario & Pac-Man Showed Up in the Rio 2016 Olympics Closing Ceremony". August 22, 2016. Archived from the original on February 5, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- "The Pac-Page (including database of Pac-Man merchandise and TV show reference)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- White, Cindy. (June 17, 2010) "E3 2010: Pac-Man Back on TV?" Archived June 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. IGN.com. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- Morris, Chris. (June 17, 2010) "Pac-Man chomps at 3D TV Archived June 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Variety.com. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- "Pac-Man Fever". Time Magazine. April 5, 1982. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

Columbia Records' Pac-Man Fever ... was No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100 last week.

- "Popular Computing". McGraw-Hill. 1982. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

Pac-Man Fever went gold almost instantly with 1 million records sold.

- Turow, Joseph (2008). Media Today: An Introduction to Mass Communication (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 554. ISBN 978-0-415-96058-8. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- RIAA Gold & Platinum Searchable Database – Pac-Man Fever . RIAA.com. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- Grosinger, Matt (February 16, 2017). "Weird Al Talks His Previously Unreleased Song "Pac-Man", Which You Can Finally Hear!". Nerdist Industries. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- Liptak, Andrew (February 18, 2017). "Listen to a previously unreleased Weird Al Beatles parody, Pac-Man". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "GORILLAZ: SONG MACHINE SEASON 1 EPISODE 5 'PAC-MAN' FT SCHOOLBOY Q". Nasty Little Man. July 20, 2020.

- "Classic video game characters unite via film 'Pixels'". Philstar. July 23, 2014. Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- Tarek Bazley: Pac-man at 35: the video game that changed the world

- "Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 redeems a gaming icon on screen". Polygon. May 8, 2017.

- "Wreck-It Ralph Trailer #2". Walt Disney Animation Studios via YouTube. September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- Cooper, Hollander; Gilbert, Henry (October 19, 2012). "Wreck-it Ralph – 9 amazing things you couldn't possibly know about the movie". Games Radar. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). Al Jazeera English, May 25, 2015

- "Shiro Sano Cast as Dr. Pacman in Kamen Rider Heisei Generations". Tokusatsu Network. November 5, 2016.

- "Relaxer Review: Help! He's Sitting and He Can't Get Up". Jeannette Catsoulis. March 28, 2019.

- "Crystal Sky, Namco & Gaga are game again". Crystalsky.com. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- Jaafar, Ali (May 19, 2008) "Crystal Sky signs $200 million deal". Variety.com. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- Coopee, Todd. "Pac-Man Turns 35!". ToyTales.ca. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015.

- "The MB Official Pac-Man Board Game". Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "The Pac-Star: Pac-Man Rub-Offs Section Index". Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- "Pac-Man". Archived from the original on October 21, 2014.

- "Pac-Man Celebrates 40th Anniversary With Minecraft DLC, a Game You Play on Twitch, and Weird AI Programs". IGN. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "Pac-Man review at OAFE". Oafe.net. Archived from the original on October 21, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- Ramsey, David. "The Perfect Man". Oxford American. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- "Pac-Man at the Twin Galaxies Official Scoreboard". Twin Galaxies. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- "Dispute Decision: Billy Mitchell's Donkey Kong & All Other Records Removed".

- "Twin Galaxies – Pac-Man (Arcade) – Points [Factory Speed]". Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "Pac-Man [Fastest Completion [Perfect Game ARCADE – 03:28:49.00 – David W Race". August 4, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- Race, David (May 30, 2013). Perfect Pac-Man: May 22, 2013 – 3hrs 28min 49sec (2 of 2). David Race. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016 – via YouTube.

- "Retro gaming pariah Billy Mitchell has Guinness records reinstated". ESPN.com. June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- Parish, Jeremy (July 23, 2013). "Remembering Pac & Pal, Pac-Man's Strangest Arcade Adventure". USgamer. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- "Pac-In-Time". Next Generation. Imagine Media (6): 113–4. June 1995.

- "Pac-Man Championship Edition for Xbox 360 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Hatfield, Daemon (November 16, 2010). "Pac-Man Championship Edition DX Review". IGN. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Mini-Arcades 'Go Gold'". Electronic Games. 1 (9): 13. November 1982. Archived from the original on August 13, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- "Coleco Mini-Arcades Go Gold" (PDF). Arcade Express. 1 (1): 4. August 15, 1982. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- "The Official Midway's Pac-Man Game Watch Instruction Manual" (PDF) (booklet). Nelsonic Industries. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "A quick look at some of the new WP7 games from Namco". BestWP7Games. November 9, 2010. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010.

- "Google gets Pac-Man fever". cnet. May 21, 2010. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010.

- https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/google-gives-pac-man-boost-with-over-223613

- "Pac-Man". Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- Ki Mae Huessner. "World's Biggest Pac-Man Is Web Sensation". ABC News Internet Ventures. Archived from the original on April 15, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

Further reading

- Trueman, Doug (November 10, 1999). "The History of Pac-Man". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 26, 2009. Comprehensive coverage on the history of the entire series up through 1999.

- Morris, Chris (May 10, 2005). "Pac Man Turns 25". CNN Money.

- Vargas, Jose Antonio (June 22, 2005). "Still Love at First Bite: At 25, Pac-Man Remains a Hot Pursuit". The Washington Post.

- Hirschfeld, Tom. How to Master the Video Games, Bantam Books, 1981. ISBN 0-553-20164-6 Strategy guide for a variety of arcade games including Pac-Man. Includes drawings of some of the common patterns.

External links

- Official website

- Pac-Man highscores on Twin Galaxies

- Pac-Man on Arcade History

- Pac-Man at the Killer List of Videogames