Oxytenanthera

Oxytenanthera is a genus of African bamboo Bamboos are members of the grass family[3][4][5] Poaceae.

| Oxytenanthera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oxytenanthera abyssinica[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Subfamily: | Bambusoideae |

| Tribe: | Bambuseae |

| Subtribe: | Bambusinae |

| Genus: | Oxytenanthera Munro |

| Species: | O. abyssinica |

| Binomial name | |

| Oxytenanthera abyssinica | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The only recognized species in this genus is Oxytenanthera abyssinica.[6] This species is found widespread across much of sub-Saharan Africa. In tropical Africa it is found outside of the humid forest zone from Senegal to Ethiopia.In Eastern Africa it is found to occur from Ethiopia all the way down to northern South Africa.

The genus formerly contained several Asiatic species, but these are now generally considered to be better suited to other genera (primarily Dendrocalamus or Gigantochloa but see also Bambusa Cephalostachyum Pseudoxytenanthera Schizostachyum Yushania);[7] However, molecular studies show species of Oxytenanthera quite distinct from Dendrocalamus spp.

Oxytenanthera is the most common lowland bamboo in eastern and central Africa, resulting in its common name of African lowland bamboo. It is also referred to as savannah bamboo[8] or Bindura bamboo.

Oxytenanthera abyssinica is a drought-resistant species of bamboo that grows in savanna woodland, semi-arid wooded grassland and thicket. It mass-flowers (gregarious flowering) after long periods of vegetative growth of more than 70 years before occasionally sets seed. The seed of Oxytenanthera abyssinic is considered rare. After setting seed the parent plant dies back, sometimes synchronously across large areas. The last known seeding period occurred in 2006 in West Africa[2] and 2010 in Ethiopia.

Uses

Traditional uses of Oxytenanthera abyssinica include weaving for basketry, as a building material for local construction, houses and furniture, and in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania in Iringa, Mbeya and Ruvuma Regions [9] it is tapped for its juice, and fermented for the production of a local alcoholic beverage.

However more recently the species has come under commercial production by EcoPlanet Bamboo.[10] Using seed from the most recent flowering event this entity has used Oxytenanthera abyssinica for the regeneration of degraded agricultural lands in South Africa’s Eastern Cape.

Through EcoPlanet Bamboo’s extensive R&D around this species and trials carried out to showcase its ability to restore degraded landscapes Oxytenanthera abyssinica has recently been touted by international institutions including the World Resources Institute as having a high potential for industrial production.[11]

Kenyan entity Kitil Farm [12] has developed a resource base of Oxytenanthera abyssinica seedlings in Isinya.

References

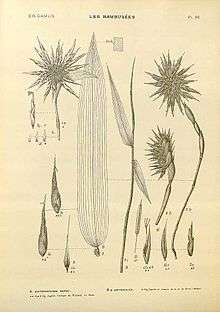

- 1913 illustration from English: Edmond Gustave Camus, Les bambusees, Atlas, vol. 2: plate 90 Source http://plantgenera.org/illustration.php?id_illustration=151808

- Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families

- "Search results — The Plant List". www.theplantlist.org. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- Ohrnberger, D. (1999). The Bamboos of the World. Elsevier Science. p. 596. ISBN 978-0-444-50020-5.

- Munro, William 1868. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London 26(1): 126-130 descriptions in Latin, commentary in English

- "Oxytenanthera abyssinica". Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Database. USDA. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Das, M., Bhattacharya, S., Singh, P., Filgueiras, T.S. and Pal, A. 2008. Bamboo taxonomy and diversity in the era of molecular markers. Advances in Botanical Research 47:225-268.

- Janzen, D.H. 1976. Why bamboos wait so long to flower. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 7:347-391.

- Mhando Leonardo (n.d.)

- http://www.ecoplanetbamboo.com/global-plantations

- http://www.worldbamboo.net/wbcx/Powerpoints/Ecology%20and%20Environment%20Concerns/ForestandLandscapeRestoration_KBuckingham_Keynote.pdf

- http://www.kitilfarm.com/

External links

- Oxytenanthera abyssinica in West African plants – A Photo Guide.

- Bamboos of India

- Common bamboo names

- Masman, W. 1995. Oxytenanthera. In: Bamboo names and synonyms.

- Mhando Leonardo (n.d.) The state of bamboo and rattan development in Tanzania. Tanzania Forest Research Institute-TAFORI.

- Pattanaik, S. and Hall, J.B. 2009. Species relationships in Dendrocalamus inferred from AFLP fingerprints. VIII World Bamboo Congress Proceedings, Vol. 5 Biology and Taxonomy; pp. 5-27 - 5-40.

- Ingram et al. 2010. The bamboo production to consumption system in Cameroon. INBAR and CIFOR.