Orient Express

The Orient Express was a long-distance passenger train service created in 1883 by Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL).

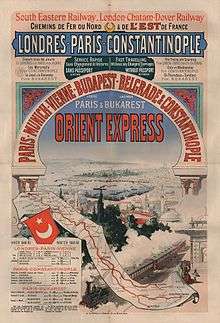

Poster advertising the winter 1888–1889 timetable | |

| Operation | |

|---|---|

| Train length | 4 to 22 coaches |

The route and rolling stock of the Orient Express changed many times. Several routes in the past concurrently used the Orient Express name, or slight variations. Although the original Orient Express was simply a normal international railway service, the name became synonymous with intrigue and luxury travel. The two city names most prominently associated with the Orient Express are Paris and Constantinople (Istanbul),[1][2] the original endpoints of the timetabled service.[3] The Orient Express was a showcase of luxury and comfort at a time when travelling was still rough and dangerous.

In 1977, the Orient Express stopped serving Istanbul. Its immediate successor, a through overnight service from Paris to Bucharest—since 1991 only to Budapest, and in 2001 again shortened to Vienna—ran for the last time from Paris on Friday 8 June 2007.[4][5] After this, the route, still called the "Orient Express", was shortened to start from Strasbourg instead,[6] occasioned by the inauguration of the LGV Est which afforded much shorter travel times from Paris to Strasbourg. The new curtailed service left Strasbourg at 22:20 daily, shortly after the arrival of a TGV from Paris, and was attached at Karlsruhe to the overnight sleeper service from Amsterdam to Vienna.

On 14 December 2009, the Orient Express ceased to operate and the route disappeared from European railway timetables, reportedly a "victim of high-speed trains and cut-rate airlines".[7] The Venice-Simplon Orient Express train, a private venture by Belmond using original CIWL carriages from the 1920s and 1930s, continues to run from London to Venice and to other destinations in Europe, including the original route from Paris to Istanbul.[8]

Train Eclair de luxe (the "test" train)

In 1882, Georges Nagelmackers, a Belgian banker's son, invited guests to a railway trip of 2,000 km (1,243 mi) on his "Train Eclair de luxe" ("lightning luxury train").[3][9] The train left Paris Gare de l'Est on Tuesday, October 10, 1882, just after 18:30 and arrived in Vienna the next day at 23:20. The return trip left Vienna on Friday, October 13 at 16:40 and, as planned, re-entered the Gare de Strasbourg at 20:00 on Saturday October 14.

Georges Nagelmackers was the founder of Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits, which expanded its luxury trains, travel agencies and hotels all over Europe, Asia, and North Africa. Its most famous train remains the Orient-Express.

The train was composed of:

- Baggage car

- Sleeping coach with 16 beds (with bogies)

- Sleeping coach with 14 beds (3 axles)

- Restaurant coach (nr. 107)

- Sleeping coach with 13 beds (3 axles)

- Sleeping coach with 13 beds (3 axles)

- Baggage car (complete 101 ton)

The first menu on board (October 10, 1882): oysters, soup with Italian pasta, turbot with green sauce, chicken ‘à la chasseur’, fillet of beef with ‘château’ potatoes, ‘chaud-froid’ of game animals, lettuce, chocolate pudding, buffet of desserts.[10]

_wagons-lits_diffusion.jpg)

Routes

Original train

On June 5, 1883, the first Express d'Orient left Paris for Vienna. Vienna remained the terminus until October 4, 1883. The train was officially renamed Orient Express in 1891.[11]

The original route, which first ran on October 4, 1883, was from Paris, Gare de l'Est, to Giurgiu in Romania via Munich and Vienna. At Giurgiu, passengers were ferried across the Danube to Ruse, Bulgaria, to pick up another train to Varna. They then completed their journey to Constantinople by ferry. In 1885, another route began operations, this time reaching Constantinople via rail from Vienna to Belgrade and Niš, carriage to Plovdiv, and rail again to İstanbul.[11]

In 1889, the train's eastern terminus became Varna in the Principality of Bulgaria, where passengers could take a ship to Constantinople. On June 1, 1889, the first direct train to Constantinople left Paris (Gare de l'Est). Istanbul, known as Constantinople until circa 1930 in English, remained its easternmost stop until 19 May 1977. The eastern terminus was the Sirkeci Terminal by the Golden Horn. Ferry service from piers next to the terminal would take passengers across the Bosphorus to Haydarpaşa Terminal, the terminus of the Asian lines of the Ottoman Railways.[11]

The onset of the First World War in 1914 saw Orient Express services suspended. They resumed at the end of hostilities in 1918, and in 1919 the opening of the Simplon Tunnel allowed the introduction of a more southerly route via Milan, Venice, and Trieste. The service on this route was known as the Simplon Orient Express, and it ran in addition to continuing services on the old route. The Treaty of Saint-Germain contained a clause requiring Austria to accept this train: formerly, Austria allowed international services to pass through Austrian territory (which included Trieste at the time) only if they ran via Vienna. The Simplon Orient Express soon became the most important rail route between Paris and İstanbul.[11]

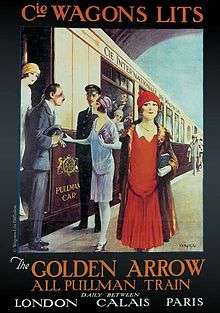

The 1930s saw the Orient Express services at its most popular, with three parallel services running: the Orient Express, the Simplon Orient Express, and also the Arlberg Orient Express, which ran via Zürich and Innsbruck to Budapest, with sleeper cars running onwards from there to Bucharest and Athens. During this time, the Orient Express acquired its reputation for comfort and luxury, carrying sleeping-cars with permanent service and restaurant cars known for the quality of their cuisine. Royalty, nobles, diplomats, business people, and the bourgeoisie in general patronized it. Each of the Orient Express services also incorporated sleeping cars which had run from Calais to Paris, thus extending the service from one end of continental Europe to the other.[11]

The start of the Second World War in 1939 again interrupted the service, which did not resume until 1945. During the war, the German Mitropa company had run some services on the route through the Balkans,[12] but Yugoslav Partisans frequently sabotaged the track, forcing a stop to this service.[11]

Following the end of the war, normal services resumed except on the Athens leg, where the closure of the border between Yugoslavia and the Kingdom of Greece prevented services from running. That border re-opened in 1951, but the closure of the Bulgarian–Turkish border from 1951 to 1952 prevented services running to İstanbul during that time. As the Iron Curtain fell across Europe, the service continued to run, but the Communist nations increasingly replaced the Wagon-Lits cars with carriages run by their own railway services.

wagons-lits_diffusion%2C_paris.jpg)

By 1962, the Orient Express and Arlberg Orient Express had stopped running, leaving only the Simplon Orient Express. This was replaced in 1962 by a slower service called the Direct Orient Express, which ran daily cars from Paris to Belgrade, and twice weekly services from Paris to İstanbul and Athens.

In 1971, the Wagon-Lits company stopped running carriages itself and making revenues from a ticket supplement. Instead, it sold or leased all its carriages to the various national railway companies, but continued to provide staff for the carriages. 1976 saw the withdrawal of the Paris–Athens direct service, and in 1977, the Direct Orient Express was withdrawn completely, with the last Paris–İstanbul service running on May 19 of that year.[4][5]

The withdrawal of the Direct Orient Express was thought by many to signal the end of the Orient Express as a whole, but in fact a service under this name continued to run from Paris to Bucharest as before (via Strasbourg, Munich, and Budapest). However, a through sleeping car from Paris to Bucharest — and even eastwards from Vienna — was only operated until 1982, and also a through seating car was only operated seasonally. This meant, that Paris–Budapest and Vienna–Bucharest coaches were running overlapped, so a journey was only possible with changing carriages — despite the unchanged name and numbering of the train. In 1991 the Budapest-Bucharest leg of the train was canceled, the new final station has become Budapest. In the summer season of 1999 and 2000 a sleeping car from Bucharest to Paris reappeared twice a week — now operated by CFR. This continued until 2001, when the service was cut back to just Paris–Vienna, already in EuroNight quality — but in both cases the coaches were in fact rather attached to a Paris–Strasbourg express. This service continued daily, listed in the timetables under the name Orient Express, until June 8, 2007.[4]

With the opening of the LGV Est Paris–Strasbourg high speed rail line on June 10, 2007, the Orient Express service was further cut back to Strasbourg–Vienna, departing nightly at 22:20 from Strasbourg, and still bearing the name,[5][11] but lost the number 262/263 which was owned for decades.

The remains of the train had a convenient connection from/to the Strasbourg-Paris TGV, but due to the less flexible prices the changing has become less attractive. In the last years through coaches between Vienna and Karlsruhe (continuing first to Dortmund, then to Amsterdam, and finally — partly from Budapest — to Frankfurt) were attached. The very last train with the name Orient-Express (now with a hyphen) departed from Vienna on the 10th of December 2009, and one day later from Strasbourg.

Route legacy

Though the final service ran only from Strasbourg to Vienna, it was possible to retrace the entire original Orient Express route with four trains: Paris–Strasbourg, Strasbourg–Vienna, Vienna–Belgrade, and Belgrade-İstanbul, each of which were operated daily. Other routes from Paris to İstanbul exist even today, such as Paris–Munich–Budapest–Bucharest–İstanbul, or Paris–Zürich–Belgrade–İstanbul, all of which have comparable travel times of approximately 60 hours without delays. Train services across the border to Turkey were stopped through several years due to construction works, but they were reintroduced in June 2017, however, ending in İstanbul's suburb Halkalı, from where a transfer bus is provided to the city centre.

The luxurious dining car, where scenes for Murder on the Orient Express and other movies were filmed, is now in the OSE museum of Thessaloníka. The local authorities plan to refit the train to make it available for tourist use around the Balkans in the near future.

Privately run trains using the name

In 1976, the Swiss travel company Intraflug AG had first hired, then also bought, several CIWL-carriages, and operated them as Nostalgie Istanbul Orient Express from Zürich to İstanbul. In 1983, the 100th anniversary of the Orient-Express was celebrated by a trip of this train from Paris to İstanbul, and in 1988 it was run to Hong Kong via the Soviet Union and China. From there it was transferred by ferry to Japan, and used there for some excursions after regauging.

After the failure of the American European Express (see below), Intraflug became bankrupt, and the carriages were taken over by the Reisebüro Mittelthurgau. The sleeping cars and some other coaches (Pullmans, dining cars, luggage vans) were transferred to Russia and used between Moscow and the Mongolian-Chinese border. (The adjacent Chinese train was also branded for a while as China Orient Express; nowadays it's known as Shangri-La Express.) The remaining vehicles were used in Germany and Switzerland as diner trains until the company's 2003 bankruptcy. Since then the trains have been standing unused in different countries, as the new owners sort out problems with operations due to a lawsuit about the usage rights of the name Orient Express.

In 1982, the Venice-Simplon Orient Express was established as a private venture, running restored 1920s and 1930s carriages from London to Venice. This service runs between March and November, and is firmly aimed at leisure travellers, with tickets costing over $3,120 per person from London to Venice (via Paris, Zürich, Innsbruck, and Verona—also, despite its name, the train is running via the Brenner Pass instead of the Simplon tunnel) including meals. Two or three times a year, Prague or Vienna and Budapest are also accessed, starting from Venice, and returning to Paris and London. Every September the train also goes from London and Paris to İstanbul via Budapest, Sinaia, and Bucharest—in the last three cities a sightseeing (and in the two capitals an overnight in hotel) also takes place—the return trip on the same route ends up in Venice. While the above-mentioned routes are available almost every year, some seasons have also included unique destinations, among them Cologne, Rome, Florence, Lucerne, the High Tatras, Kraków, Dresden, Copenhagen, and Stockholm. Such a journey is provided currently to Berlin.

The company also offers a similarly themed luxury train in Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand called the Eastern and Oriental Express, and operates other luxury overnight trains in Scotland, Ireland, and Peru.

The Pullman Orient Express was established by the CIWL in 1994. This train has only Pullman and dining cars, but no sleepers. It's used for gourmet trips in France. After the legal disputes about the name it was taken over by the SNCF and operated since then as Pullman Orient-Express.

In North America, the American Orient Express, formerly the American European Express and later GrandLuxe Express, operated several train sets in charter service between 1989 and 2008.

_wagons-lits_diffusion.jpg)

CIWL phototheque and historical archives

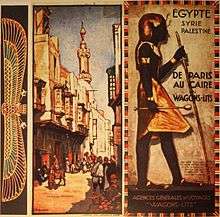

The CIWL archives contain more than 100 years of posters, photos, plans, and communication material that represents a tremendous interest for cultural, academic, or commercial projects. Creators and artists have been hired by CIWL since 1883 in order to create luxury conditions and comfort in travel, as well as a particular graphic style that is now recognized worldwide by its quality. Great efforts have been made to digitalize images (photos, plans, and posters), although vast paper archives remain preserved, waiting to be sorted and classified in the future. As of today, available digital archives consist of more than 250 CIWL posters, 800 PLM posters, and more than 6,000 archive photos, representing probably one of the most extensive poster collections in the world with works dating from the end of the 19th century to the late 1950s. These archives are regularly used for all types of publishing and media projects, all over the world, as well as cultural events (see below: Exhibition).[13][14]

_wagons-lits_diffusion_paris.jpg)

In popular culture

The glamour and rich history of the Orient Express has frequently lent itself to the plot of books and films and as the subject of television documentaries.

Literature

- Dracula (1897) by Bram Stoker: whilst Count Dracula escapes from England to Varna by sea, the cabal sworn to destroy him travels to Paris and takes the Orient Express, arriving in Varna ahead of him.

- Stamboul Train (1932) by Graham Greene

- The short story "Have You Got Everything You Want?" (1933), by Dame Agatha Christie

- Murder on the Orient Express (1934) by Dame Agatha Christie, one of the most enduring tales that take place on the Simplon Orient Express[11]

- Oriënt-Express (1934) a novel by A. den Doolaard: it takes place in North Macedonia.

- From Russia, with Love (1957), a James Bond novel by Ian Fleming

- Travels with My Aunt (1969) by Graham Greene

- Paul Theroux (1975) devotes a chapter of The Great Railway Bazaar to his journey from Paris to İstanbul on the Direct-Orient Express.

- The Orient Express (1992) a novel by Gregor von Rezzori follows a European American who, having ridden the original Orient Express in his youth, returns late in life to ride the refurbished version.

- Flashman and the Tiger (1999) by George MacDonald Fraser: Sir Harry Paget Flashman travels on the train's first journey as a guest of the journalist Henri Blowitz.

- The Orient Express appeared in the 2004 novel Lionboy and its sequel Lionboy: The Case by Zizou Corder. Charlie Ashanti was stowing away on the train on his way to Venice when he met King Boris of Bulgaria.

- The short story "On the Orient, North" by Ray Bradbury

- The Orient Express appeared as a technologically advanced (for its time) train in the book Behemoth, by Scott Westerfeld.

- Thea Stilton And The Mystery On The Orient Express by Elisabetta Dami

- Madness on the Orient Express is an anthology of horror stories, all connected to the Orient Express, edited by James Lowder.

- First Class Murder (2015) by Robin Stevens from the A Murder Most Unladylike series is set on The Orient Express.

Film

- Orient Express (1934), film adaptation of Graham Greene's Stamboul Train.

- Orient Express (1944), German film about a murder on the train.

- Sleeping Car to Trieste (1948), film by the Rank Organisation, story by Clifford Grey. A stolen diplomatic document is the quest of various groups on the Orient Express from Paris to Trieste. Copyright by Two Cities Films Ltd.

- Orient Express (1954), whose plot revolves around a two-day stop at a village in the Alps by passengers on the Orient Express.

- From Russia with Love (1963): James Bond, along with Bond girl Tatiana Romanova and ally Ali Kerim Bey, tries to travel on the Orient Express from Istanbul to Trieste, but complications involving SPECTRE assassin Red Grant force Bond and Tatiana to jump off the train in Yugoslav Istria.

- Istanbul Express (1968): thriller, made for television, starring Gene Barry.

- Travels with My Aunt (1972): Henry Pulling accompanies his aunt, Augusta Bertram, on a trip from London to Turkey. The two board the Orient Express in Paris; the train takes them to Turkey (though they disembark briefly at the Milan stop).

- Minder on the Orient Express (1985) is a comedy/thriller television film made as a spin-off from the successful television series Minder. It was first broadcast on Christmas Day 1985, as the highlight of that year's ITV Christmas schedule.

- Murder on the Orient Express (1974), (2001), (2010), and (2017): Film adaptations of the Agatha Christie novel.

- Romance on the Orient Express (1985): TV movie with Cheryl Ladd.

- 102 Dalmatians (2000)

- Death, Deceit and Destiny Aboard the Orient Express (2000)

- Around the World in 80 Days (2004): Mr Fogg travels on the train to İstanbul.

- Orient Express (2004)

- Murder Mystery (2019): In the final scene Nick and Audrey Spitz are travelling on the Orient Express.

- ’’007-from Russia with love (1963)’’ James Bond travels from Istanbul to Trieste on board the orient express.

Television

- Orient Express was a syndicated TV series in the early- to mid-1950s. Filmed in Europe, its half-hour dramas featured such stars as Paul Lukas, Jean-Pierre Aumont, Geraldine Brooks and Erich von Stroheim.

- In “The Orient Express” (episode number 48 of The World of Commander McBragg cartoon series), the Commander tells the story of how he once rode on that fabled train, dodging several assassination attempts on his life en route.

- Daylight Robbery on the Orient Express, an episode of the award-winning British comedy television series The Goodies, was first broadcast on 5 October 1976 and is partially set aboard the train.

- Mystery on the Orient Express: a television special featuring illusionist David Copperfield. During the special, Copperfield rode aboard the train and, at its conclusion, made the dining car seemingly disappear.

- "The Istambul Train", "Il treno d'Istanbul" (1980) Hungarian–Italian television series "Stamboul Train" original title by Graham Greene (1932).[15]

- "Minder on the Orient Express" (1985): a special episode of the long-running ITV sit-com Minder.

- Whicker's World – Aboard The Orient Express: Travel journalist Alan Whicker joined the inaugural service of the Venice-Simplon Orient Express to Venice in 1982, interviewing invited guests and celebrities along the way.

- Gavin Stamp's Orient Express: in 2007 UK's Five broadcast an arts/travel series which saw the historian journey from Paris to Istanbul along the old Orient Express route.

- The 1987 cartoon Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles had an episode titled "Turtles on the Orient Express". As the title suggests it is primarily based on the train.[16]

- A 1993 advert for Bisto Fuller Flavour Gravy Granules featured in it with a young couple.

- The 1995 cartoon Madeline had an episode titled Madeline on the Orient Express, in which a chef stole a snake.

- The episode "Emergence" of the science fiction television series Star Trek: The Next Generation partially takes place on a Holodeck representation of the Orient Express.

- On the 15 May 2007 broadcast of Jeopardy!, the think music was played by a person on the train's piano, since the Final Jeopardy clue was about the Orient Express.

- In the British soap opera EastEnders, in 1986, characters Den and Angie Watts spent their honeymoon on the train. It was also where it was revealed that Angie was lying about her illness, preceding the ultimate storyline on Christmas Day 1986.

- "Aboard the Orient Express" Get Smart series 1, episode 13 is set on the Orient Express, though filmed on set.

- In one episode of the British cartoon series Danger Mouse, called "Danger Mouse on the Orient Express" (a parody of Murder on the Orient Express), Danger Mouse and Penfold travel on the train on their way back to London from Venice. Danger Mouse's arch enemy Greenback is also on the train.

- In an episode of the television series Chuck, Chuck and Sarah decide to go AWOL and take a trip on the Orient Express.

- At the end of the Doctor Who episode "The Big Bang", the Doctor receives a call for help from the "Orient Express — in space". This setting is used in the episode "Mummy on the Orient Express", including a reference to the ending of "The Big Bang", four years later.

- In episode 15 of television series Forever (U.S. TV series), Dr Henry Morgan travelled from Budapest to İstanbul with his wife Abigail Morgan on his honeymoon in 1955. He performed an appendectomy on a member of the fictional Urkesh royalty.

- The Backyardigans episode "Le Master of Disguise" features the Orient Express, showing Uniqua, Pablo, Austin, Tasha and Tyrone going to Istanbul from Paris.

- In an episode titled Murder on the Orient Express of Agatha Christie's Poirot, Poirot investigates the murder of a shady American businessman stabbed in his compartment on the Orient Express when it is blocked by a blizzard in Croatia.

- Michael Palin's Around The World In Eighty Days (1988). Michael Palin travelled on the Orient Express in episode 1 from London Victoria to Innsbruck, using a ferry across the English Channel from Folkestone. The train didn't continue on to Venice because of a strike on the Italian railways.

Music

- Alex Otterlei’s “Horror on the Orient Express” is inspired by the Call of Cthulhu RPG. The integral symphonic version was released on CD in 2002, a 26-minute Suite for Concert Band was published in 2012.

- Orient Expressions: Musical group from Turkey who combine traditional Turkish music with elements of electronica.

- The Jean Michel Jarre album The Concerts in China has a track entitled "Orient Express" as track 1 of disc 2, though the relation to the train is unknown.

- A concert band piece, Orient Express is written by Philip Sparke.

- There was a band based in Hawaii called Liz Damon's Orient Express.

Games and animation

- The role-playing game Call of Cthulhu RPG used the train for one of its more famous campaigns, Horror on the Orient Express.

- The TSR role-playing game Top Secret had a 1983 module based on the Orient titled "Operation Orient Express".

- Heart of China has a final sequence in the Orient Express. An action scene takes place on the roof.

- The Orient Express plays host to an adventure game by Jordan Mechner: The Last Express is a murder mystery game set around the last ride of the Orient Express before it suspended operations at the start of World War I. Robert Cath, an American doctor wanted by French police as he is suspected of the murder of an Irish police officer, becomes involved in a maelstrom of treachery, lies, political conspiracies, personal interests, romance and murder. The game has 30 characters representing a cross-section of European forces at the time.

- The Adventure Company developed a point-and-click adventure based on Agatha Christie's novel, Agatha Christie: Murder on the Orient Express.

- The 1987 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon spent the better part of an episode on the train.

- In 1994's season 1 episode of Where on Earth Is Carmen Sandiego? called, "The Gold Old Bad Days", Carmen Sandiego and her V.I.L.E. gang are given a challenge to do something low tech by The Player robbery. Carmen's goal is the train.

- The train is featured in Microsoft Train Simulator, where its route is a 101 kilometres (63 mi) section from Innsbruck to Sankt Anton am Arlberg in Austria.

- The Orient Express was featured in two scenarios in the Railroad Tycoon series:

- In Railroad Tycoon II, players get to connect Paris to Constantinople in a territory buying challenge.

- In Railroad Tycoon 3 players need to connect Vienna to Istanbul.

- The Orient Express cars were made available for download to use in Auran's Trainz Railroad Simulator 2004 or later versions by the content creation group: FMA.

- In the game Crash Bandicoot 3: Warped for PS1, the third level (which is Asian-themed) is named after Orient Express.

- The first scenes of The Raven: Legacy of a Master Thief, a 2013 game for PC, involve a mystery set amongst train carriages inspired by the Orient Express.

- The entire Orient Express set was used in the Facebook game, TrainStation.

- The Orient Express is a usable engine and caboose in the mobile game Tiny Rails.

Exhibitions

See also

- Lists of named passenger trains

- Orient-Express Hotels

- The Last Express

References

Notes

- "Orient-Express - train".

- "Orient-Express". www.orient-express.eu.

- Zax, David (1 March 2007). "A Brief History of the Orient Express". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Calder, Simon (22 August 2009). "Murder of the Orient Express – End of the line for celebrated train service". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- "A History of the Orient Express". Agatha Christie Limited. 17 May 2011. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- "'hidden europe' magazine e-news Issue 2007/15". 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- "The Orient Express Takes Its Final Trip". NPR. December 12, 2009. Retrieved 2011-02-26.

- "Venice Simplon-Orient-Express - Luxury Train from London to Venice". www.vsoe.com.

- Lambert, Anthony (21 January 2013). "The Orient-Express: Great Train Journeys". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Piegsa-quischotte, Inke. "Memories of the Orient Express". Travel Through History. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Smith, Mark. "A history of the Orient Express". Seat Sixty One. www.seat61.com. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- "The Orient Express – Across Europe from London to Istanbul". Eng Rail History. engrailhistory.info. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Unauthorized use of CIWL property is illegal. For any request, contact www.wagons-lits-diffusion.com

- "compagnie des wagons-lits, orient-express, plm". www.wagons-lits-diffusion.com.

- "The Istambul Train (TV Mini-Series 1980– )" – via www.imdb.com.

- Ninjaturtles: Turtles on the Orient Express

- "Il était une fois l'Orient Express". 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

Bibliography

- James B. Sherwood; Ivan Fallon (13 April 2012). Orient-Express: A Personal Journey. Robson Press. ISBN 978-1-84954-187-9. Retrieved 13 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Orient Express: The Life and Times of the World's Most Famous Train by E H Cookridge.

Detail from a copy of the first publication of the book with black and white plates by Allen Lane London in 1979 (ISBN 978-0-7139-1271-5)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orient Express. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Orient Express. |

.svg.png)