Orange Line (Washington Metro)

The Orange Line is a rapid transit line of the Washington Metro system, consisting of 26 stations in Fairfax County and Arlington, Virginia; the District of Columbia; and Prince George's County, Maryland, United States. The Orange Line runs from Vienna in Virginia to New Carrollton in Maryland. Half of the line's stations are shared with the Blue Line and over two thirds are shared with the Silver Line. Orange Line service began on November 20, 1978.

Since August 16, 2020, trains are terminating at West Falls Church due to Platform reconstruction at East Falls Church, , Dunn Loring–Merrifield, and Vienna/Fairfax–GMU.[1][2] Between May 23 and August 15, 2020, trains terminated at Ballston–MU when West Falls Church was being rebuilt.[3] Shuttle buses are provided to the closed stations.

History

Planning for Metro began with the Mass Transportation Survey in 1955, which attempted to forecast both freeway and mass transit systems sufficient to meet the needs of transportation in 1980.[4] In 1959, the study's final report included two rapid transit lines which anticipated subways in downtown Washington.[5] Because the plan called for extensive freeway construction within the District of Columbia, alarmed residents lobbied for federal legislation creating a moratorium on freeway construction through July 1, 1962.[6] The National Capital Transportation Agency's 1962 Transportation in the National Capital Region report anticipated much of the present Orange Line route in Virginia with the route following the median strip of I-66 both inside Arlington and beyond.[7] The route continued in rapid transit plans until the formation of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA).

With the formation of WMATA in October 1966, planning of the system shifted from federal hands to a regional body with representatives of the District, Maryland and Virginia. Congressional route approval was no longer a key consideration.[8] Instead, routes had to serve each local suburban jurisdiction to assure that they would approve bond referenda to finance the system.[9] Because the least expensive way to build into the suburbs was to rely upon existing railroad right-of-ways, the Orange Line took much of its present form, except that it also featured a further extension along the railroad to Bowie, Maryland and along the Dulles Access Road to the Dulles Airport.[10]

By 1966, WMATA and Arlington County planners had agreed "to realign the rapid transit through high-density commercial-office-apartment areas in the vicinity of Wilson Boulevard instead of the freeway's median between the river and Glebe Road."[11] As a result of this agreement, the Orange Line follows in Arlington the former routes of an interurban electric trolley line, the Fairfax line and the North Arlington branch of the Washington, Arlington & Falls Church Railway, that had initially spurred those areas' development.[12]

On March 1, 1968, WMATA approved its Adopted Regional System (ARS) plan that included suburban mass transit lines that followed the median of the proposed Interstate 66 through Virginia to Vienna and the CSX/Amtrak railroad right-of-way in Prince George's County, Maryland.[13] The construction of the downtown Washington sections of the Orange and Blue lines began simultaneously with the Red line. A joint ground-breaking ceremony was held on December 9, 1969.[13] Service on the joint downtown track was at first branded as just the Blue Line and commenced on July 1, 1977.[13]

In 1976, Robert Patricelli, federal Urban Mass Transportation Administrator, ordered Metro to conduct an alternatives analysis of the portion of its system that was not already under contract.[14] Because the Tysons Corner area of Fairfax County had developed significantly since the ARS was adopted in 1968, the analysis considered rerouting the Orange line to serve Tysons Corner at an additional cost of $60 million. However, because environmental impact statements had already been completed for the Vienna route, a change in the route would result in a five-year delay in the construction of the Orange Line west of Ballston. This prompted the City of Falls Church to sue WMATA for breach of contract. In the end, WMATA kept the Vienna route intact, leaving Tysons Corner without Metrorail service until 2014.[15][16]

Service on the Orange Line began on November 20, 1978 between National Airport and New Carrollton, with five new stations being added to the existing network from Stadium–Armory. When the line from Rosslyn to Ballston–MU was completed on December 11, 1979, Orange Line trains began following this route rather than going to the National Airport station. The line was completed on June 7, 1986, when it was extended by four stations to Vienna in the I-66 median.[13]

On January 13, 1982, an Orange Line train derailed as it was being backed up from an improperly closed rail switch between the Federal Triangle and Smithsonian stations, resulting in the deaths of three passengers.[17] It was the first incident within the Metro system that caused a fatality,[17] and the deadliest incident occurring in the system until the 2009 collision that resulted in nine fatalities.[18]

Between 2011 and 2013, service was interrupted at stations west of Ballston on designated weekends to accommodate the construction of the interconnection of the Silver Line with the existing Orange Line tracks.[19][20][21] As a part of this project, the train yard adjacent to the West Falls Church station on the Orange Line was expanded.[22][23]

On July 26, 2014, Orange Line stations between East Falls Church and Stadium-Armory began to serve Silver Line trains.

From March 26, 2020 until June 28, 2020, trains were bypassing East Falls Church, Virginia Square–GMU, Clarendon, Federal Triangle, Smithsonian, Federal Center SW, and Cheverly stations due to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.[24][25] All stations reopened on June 28, 2020.[26]

From May 23 until August 15, 2020, trains are terminating at Ballston–MU due to Platform reconstruction at East Falls Church, West Falls Church, Dunn Loring–Merrifield, and Vienna/Fairfax–GMU.[27][28] The original plan was supposed to terminate at West Falls Church, but was instead changed to Ballston due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and low ridership. Shuttle buses are provided to the closed stations. On August 16, 2020, all Orange line trains began terminating at West Falls Church while bypassing East Falls Church.[29]

Route

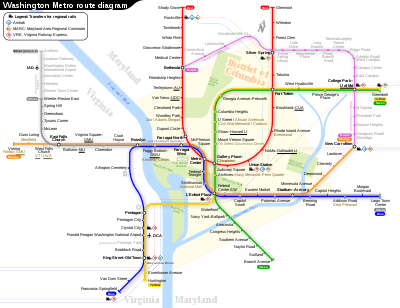

Starting at its western terminus at the Vienna/Fairfax-GMU station in Virginia, the tracks run on the median strip of Interstate 66 until they enter a tunnel under Fairfax Drive just before the Ballston-MU station.[30] Although originally proposed to follow I-66 through Arlington, city planners successfully argued that the line be relocated to Fairfax Drive, which has since stimulated high rise development along the line's route. At the Clarendon station, the tunnel shifts to Wilson Blvd. and 16th Street North.[30] The tunnel then turns north and merges with the Blue Line just before entering the Rosslyn station which is located under North Lynn Street.[30] The tunnel continues under the Potomac River and bends to the east to travel under I Street NW in the District of Columbia.[30]

The tunnel continues east under I Street and between Farragut West and McPherson Square stations there is a non-revenue branch track that connects with the Red Line. The tunnel then turns south under 12th Street Northwest and enters the lower level of the Metro Center station.[30] After Smithsonian station, the tunnel turns east under D Street Southwest and then southeast under Pennsylvania Avenue Southeast.[30] At Potomac Avenue station, the tunnel briefly travels under G Street Southeast and then turns northwest under Potomac Avenue with a turn to the north to travel under 19th Street Southeast for the Stadium-Armory station.[30] The tunnel then travels under the RFK Stadium parking lots to surface near Benning Road.[30] The elevated tracks follow Benning Road across the Anacostia River and then split from the Blue and Silver lines. There is a pocket track just west of this split.

The above ground tracks continue along DC Route 295 between Minnesota Avenue and Deanwood stations and then follow the CSX/Amtrak railroad in Prince George's County, Maryland to the eastern terminus at New Carrolton.[30] The route includes a train yard adjacent to the West Falls Church station.[22] Orange Line service travels along the entirety of the K Route (from the terminus at Vienna/Fairfax-GMU to the C & K junction just south of Rosslyn), part of the C Route (from the C & K junction just south of Rosslyn to Metro Center), and the entire D Route (from Metro Center to New Carrollton).[31]

The Orange Line needs 30 trains (9 eight-car trains and 21 six-car trains, consisting of 198 rail cars) to run at peak capacity.[32]

Stations

The following stations are along the line, from west to east:

| Station | Code | Opened | Terrain | Other Metro Lines |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vienna | K08 | 1986 | surface; median of I-66 | Western terminus | |

| Dunn Loring | K07 | 1986 | surface; median of I-66 | ||

| West Falls Church | K06 | 1986 | surface; median of I-66 | ||

| East Falls Church | K05 | 1986 | surface; median of I-66 | Transfer station for the Silver Line (western) | |

| Ballston–MU | K04 | 1979 | underground | ||

| Virginia Square–GMU | K03 | 1979 | underground | ||

| Clarendon | K02 | 1979 | underground | ||

| Court House | K01 | 1979 | underground | ||

| Rosslyn | C05 | 1977 | underground | Transfer station for the Blue Line (western). | |

| Foggy Bottom–GWU | C04 | 1977 | underground | ||

| Farragut West | C03 | 1977 | underground | Walking transfer to Red Line at Farragut North (branded as "Farragut Crossing") | |

| McPherson Square | C02 | 1977 | underground | ||

| Metro Center | C01 | 1977 | underground | Transfer station for Red Line | |

| Federal Triangle | D01 | 1977 | underground | ||

| Smithsonian | D02 | 1977 | underground | ||

| L'Enfant Plaza | D03 | 1977 | underground | transfer station for the Yellow and Green Lines | |

| Federal Center SW | D04 | 1977 | underground | ||

| Capitol South | D05 | 1977 | underground | ||

| Eastern Market | D06 | 1977 | underground | ||

| Potomac Avenue | D07 | 1977 | underground | ||

| Stadium–Armory | D08 | 1977 | underground | Transfer station for the Blue and Silver lines (east) | |

| Minnesota Avenue | D09 | 1978 | surface | ||

| Deanwood | D10 | 1978 | surface | ||

| Cheverly | D11 | 1978 | surface | ||

| Landover | D12 | 1978 | surface | ||

| New Carrollton | D13 | 1978 | surface | MTA Purple Line (planned) Eastern terminus |

.jpg)

Future

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) announced on January 18, 2008 that it and the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (VDPRT) had begun work on a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) for the I-66 corridor in Fairfax and Prince William counties. According to VDOT the EIS, officially named the I-66 Multimodal Transportation and Environment Study, would focus on improving mobility along I-66 from the Capital Beltway (I-495) interchange in Fairfax County to the interchange with U.S. Route 15 in Prince William County. The EIS also allegedly includes a four station extension of the Orange Line past Vienna. The extension would continue to run in the I-66 median and would have stations at Chain Bridge Road, Fair Oaks, Stringfellow Road and Centreville near Virginia Route 28 and U.S. Route 29.[33][34] Also, plans to extend Orange Line to Bowie have been proposed. In its final report published June 8, 2012, the study and analysis revealed that an "extension would have a minimal impact on Metrorail ridership and volumes on study area roadways inside the Beltway and would therefore not relieve congestion in the study corridor."[35]

References

- "Metro to use upcoming low-ridership summer to maximum effect, expands Orange, Silver line shutdown". www.wmata.com. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "Platform Improvement Project | WMATA". www.wmata.com. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Silver Line service will return August 16, along with reopening of six stations in Fairfax County | WMATA". www.wmata.com. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- Schrag (2006), p. 33-38.

- Schrag (2006), p. 39.

- Schrag (2006), p. 42.

- Schrag (2006), p. 55.

- Schrag (2006), p. 104.

- Schrag (2006), p. 108.

- Schrag (2006), p. 110.

- Northern Virginia Transportation Commission, Potential Rail Transit Corridors at p. 1, quoted in Schrag at p. 224.

- (1)

""Lacey Car Barn" marker". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

In 1896, the Washington, Arlington & Falls Church Railway began running electric trolleys from Rosslyn to Falls Church on the present routes of Fairfax Drive and I-66. By 1907, the line linked downtown Washington to Ballston, Vienna, and the Town of Fairfax. .... The line to Fairfax closed in 1939, but Metrorail’s Orange Line follows its route through Arlington. ..... Marker is in Arlington, Virginia, in Arlington County. Marker is at the intersection of Fairfax Drive and Glebe Road (Virginia Route 120), on the right when traveling west on Fairfax Drive.

(2) ""Ballston" marker". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2017.By 1900 a well-defined village called Central Ballston had developed in the area bounded by the present Wilson Boulevard, Taylor Street, Washington Boulevard, and Pollard Street. More diffuse settlement extended westward to Lubber Run and southward along Glebe Road to Henderson Road. The track of the Washington, Arlington, and Falls Church Electric Railroad ran along what is now Fairfax Drive; the Ballston Station was at Ballston Avenue, now Stuart Street. ...

- "Metro History" (PDF). WMATA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2004. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- Schrag (2006), p. 187.

- Schrag (2006), p. 238-239.

- "Dulles Metrorail – Silver Line Metrorail Service Begins". Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. Archived from the original on July 31, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- Stephen J. Lynton (January 14, 1982). "Metro Train -Derails; 3 Die". The Washington Post.

- "At Least 7 Killed in Deadliest Collision in D.C. Metro History". NBC Washington. June 22, 2009. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- Rein, Lisa (December 4, 2009). "Extensive testing in new safety plan for Metro bridge". The Washington Post. p. B4. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- "Construction of rail to Dulles to halt service between East Falls Church and West Falls Church during the weekends of March 11–13 and March 18–20". WMATA. March 9, 2011. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- Thomson, Robert (January 11, 2011). "Many Metrorail disruptions ahead". Washington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- Hosh, Kafia A. (February 22, 2010). "Rail yard's neighbors cringe over Silver Line staging, noise". Washington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- Hosh, Kafia A. (January 16, 2011). "Falls Church community braces for rail yard expansion". Washington Post. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- "Special Covid-19 System Map" (PDF). Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "Metrorail stations closed due to COVID-19 pandemic". Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. March 23, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "Metro to reopen 15 stations, reallocate bus service to address crowding, starting Sunday | WMATA". www.wmata.com. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "Metro to use upcoming low-ridership summer to maximum effect, expands Orange, Silver line shutdown". www.wmata.com. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- "Platform Improvement Project | WMATA". www.wmata.com. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Silver Line service will return August 16, along with reopening of six stations in Fairfax County | WMATA". www.wmata.com. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- Metro Washington D.C. Beltway (Map) (2000–2001 ed.). 1:38016. AAA. 2000.

- Schrag (2006), p. 188.

- "Approved Fiscal 2009 Annual Budget" (PDF). Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. 2009. p. 80. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2012.

- "I-66 Multimodal Transportation and Environmental Study". Archived from the original on July 31, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

- Schrag, Zachary (2006). The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8246-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Orange Line (Washington Metro). |

- world.nycsubway.org: Orange Line