Oderzo

Oderzo (Latin: Opitergium; Venetian: Oderso) is a town and comune in the province of Treviso, Veneto, northern Italy. It lies in the heart of the Venetian plain, about 66 kilometres (41 miles) to the northeast of Venice. Oderzo is traversed by the Monticano River, a tributary of the Livenza.

Oderzo | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Oderzo | |

Piazza Grande (Main Square). | |

Coat of arms | |

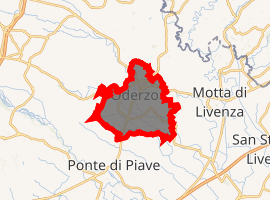

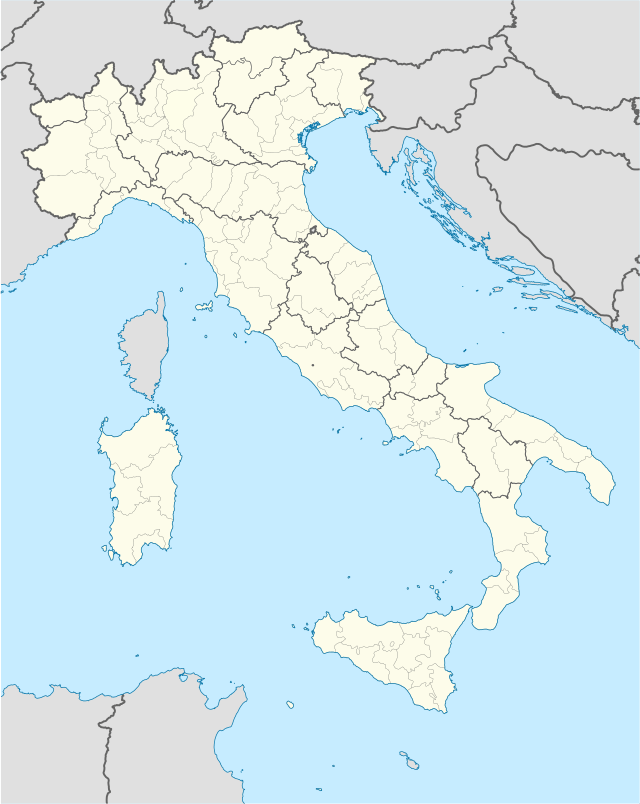

Location of Oderzo

| |

Oderzo Location of Oderzo in Italy  Oderzo Oderzo (Veneto) | |

| Coordinates: 45°46′48″N 12°29′17″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Veneto |

| Province | Treviso (TV) |

| Frazioni | Camino, Colfrancui, Faè, Fratta, Rustignè, Piavon |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Maria Scardellato |

| Area | |

| • Total | 42 km2 (16 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 14 m (46 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2015)[2] | |

| • Total | 20,413 |

| • Density | 490/km2 (1,300/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Opitergini |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 31046 |

| Dialing code | 0422 |

| Patron saint | San Tiziano |

| Saint day | 16 January |

| Website | Official website |

The centro storico, or town center, is rich with archeological ruins which give insight into Oderzo's history as a notable crossroad in the Roman Empire.

Political division

The six suburbs or frazioni which surround Oderzo almost in the form of a hexagon. Starting from the north and then proceeding clockwise, they are:

|

|

History

Venetic period

The earliest settlement of the area can be dated to the Iron Age, around the 10th century BC. From the mid-9th century BC the Veneti occupied site and gave it its name. Etymologically, "-terg-" in Opitergium stems from a Venetic root word indicating a market (q.v. Tergeste, the old name of Trieste). The location of Oderzo on the Venetian plain and between the Monticano and Navisego[3] rivers made it ideal as a center for trade.

Roman Republic Period

The Veneti of Oderzo appear to have maintained friendly relations with the Romans and the population was gradually Romanized after the Romans moved into the area around 200 BC. The town was granted Latin rights in 182 BC. The Via Postumia, finished in 148 BC, passing through Oderzo, connected Genua to Aquileia, and thus, increased the importance of Oderzo.

Citizens of Oderzo likely were involved in the Social War in 89 BC since acorn-like missiles with names in Venetic and Latin inscriptions have been found at Ascoli Piceno.[4]

During the Roman Civil War, Caius Volteius Capito, a centurion born in Oderzo, led a number of men from the town to fight on the side of Julius Caesar against Pompey.[5] For their loyalty, Caesar exempted Oderzo from conscription for 20 years and enlarged its territory.[6] Moreover, in 48 BC the city was elevated to the rank of Roman municipium and its citizens assigned to the Roman tribe Papiria by the Lex de Gallia Cisalpina.

Roman Empire Period

With the reforms of Augustus Oderzo was incorporated into Regio X of Italia, Venetia et Histria. The Roman era witnessed prodigious building projects including a forum, a basilica, temples and many private homes.

Oderzo achieved its greatest splendor during the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Its population grew to about 50,000 inhabitants. It lent its name to the Venetian lagoon which was called laguna opitergina and to the mountains of Cansiglio which were called montes opitergini. A number of Roman authors mention the city, among whom are Claudius Ptolomeus, Strabo,[7] Pliny the Elder,[8] Lucan,[9] Tacitus,[10] Livy and Quintilian.

Unfortunately, prosperity made Oderzo a target. During the Marcomannic Wars in 167 AD, Oderzo was sacked and destroyed by a force of Marcomanni and Quadi, who then went on to besiege Aquileia.[11] By the 5th century, Oderzo shared the fate of the rest of Venetia and had to deal with attacks in 403 by the Visigoths led by Alaric, in 452 by the Huns whose leader, Attila, according to a local legend hid a treasure in a town's pit, in 465 during a revolt of Visigothic and Roman soldiers who objected to the rule of Severus and in 473 by the Ostrogoths who took control of Rome and all of Italy after 476.

Late Antiquity

By 554, the town was restored to the Empire by Justinian's devastating Gothic War in Italy. Under the Byzantine Empire, Oderzo became the a major center within the Exarchate of Ravenna with a dux as its chief official. It would be held by the Byzantines, even after much of northern Italy was conquered by the Lombard in 568, until its destruction by the Lombard king Grimoald in 667/8.

Paul the Deacon attributes the Lombard hatred for the city to the perfidy of a certain citizen of Oderzo, a "patricius Romanorum" named Gregory, who in 641 while under the promise of a truce beheaded Taso and Cacco, sons of Gisulf, the Lombard duke of Forum Iulium. The Lombard king, Rothari, subsequently led a war of vendetta and, having breached Oderzo's defenses, inflicted upon it severe devastation. However, the Lombards apparently withdrew, since in 667, Oderzo was again in the hands of the Byzantines. In that year, Lombard king, Grimoald I, still holding a grudge for the murder of Taso and Cacco, laid siege to Oderzo. Much of its population fled to the nearby cities of Heraclea and Equilium still under Byzantine control. According to Venetian tradition, one of the refugees from Oderzo was the first Doge of Venice, Paolo Lucio Anafesto. After his victory, Grimoald destroyed the city and divided its territory between the dukes of Tarvisium, Forum Iulium, and Ceneta, with the bulk going to Ceneta.[12]

Middle Ages

It was not until about AD 1000 that Oderzo again gained relative importance. Over time, the town had grown again around a castle. It would be contested between the bishops of Belluno and Ceneda, the comune of Treviso and the feudal da Camino (originary of the Camino castle, now part of Oderzo) and da Romano families until 1380 when it became a stable possession of the Republic of Venice.

Modern era

Oderzo was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy in 1866. In 1917, during World War I, the town was damaged in the aftermath of the Italian rout at Caporetto.

In 1943 it was a centre of the civil war between the German puppet Italian Social Republic (RSI) and the partisan resistance. In 1945, 120 people suspected of allegiance to the RSI were executed (see Oderzo Massacre).

The city was governed by the Italian Christian Democratic party from 1945–1993, and lived a notable economic boom, which also attracted a massive immigration from the southern Italy regions.

The Ciclocross del Ponte Faè di Oderzo is a cyclo-cross race held in December.

Main sights

- The Piazza Grande

- The Duomo (Cathedral) of St. John the Baptist, begun in the 11th century over the ruins of the Roman temple of Mars, and re-consecrated in 1535. The original Gothic-Romanesque appearance has been modified by the subsequent renovations. It includes some notable works by Pomponio Amalteo.

- Archaeological area of the Roman Forum. It includes the remains of the basilica and a wide staircase.

- Torresin (watchtower)

- The Renaissance Palazzo Porcia e Brugnera.

- The former Prisons (Porta Pretoria). It includes the remains of a Middle Ages prison, whose most famous guest was the troubadour Sordello da Goito.

In the frazione of Colfrancui is the mysterious Mutera, an artificial hill of the Adriatic Veneti, probably used as an observatory.

Notable people

- Amedeo Obici, American entrepreneur born in Oderzo

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Population data from Istat

- The Navisego is now filled in with sediment, but the Piavon canal follows part of its course.

- E. Mangani, F. Rebecchi, and M.J. Srazzulla, Emilia Venezie (Bari: Laterza & Figli, 1981), 191.

- Lucan, Pharsalia, B.IV.1.462

- Livy, Ep. 110; Florus, II.13.33

- Geografia, (in English)lib. V, cap. I, par. 8.

- Naturalis Historia, lib. III.

- Pharsalia, lib. IV.

- Histories lib. III, cap.VI

- Ammianus Marcellinus, book 29, 6, 1

- Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards, IV.38-45

Sources

- Brisotto, G.B. (1999). Guida di Oderzo.