Ophiocordyceps unilateralis

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis is an insect-pathogenic fungus, discovered by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in 1859, and currently found predominantly in tropical forest ecosystems. O. unilateralis infects ants of the Camponotini tribe, with the full pathogenesis being characterized by alteration of the behavioral patterns of the infected ant. Infected hosts leave their canopy nests and foraging trails for the forest floor, an area with a temperature and humidity suitable for fungal growth; they then use their mandibles to attach themselves to a major vein on the underside of a leaf, where the host remains after its eventual death.[2] The process leading to mortality takes 4–10 days, and includes a reproductive stage where fruiting bodies grow from the ant's head, rupturing to release the fungus's spores. O. unilateralis is, in turn, also susceptible to fungal infection itself, an occurrence that can limit its impact on ant populations, which has otherwise been known to devastate ant colonies.

| Ophiocordyceps unilateralis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dead ants infected with Ophiocordyceps unilateralis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Sordariomycetes |

| Order: | Hypocreales |

| Family: | Ophiocordycipitaceae |

| Genus: | Ophiocordyceps |

| Species: | O. unilateralis |

| Binomial name | |

| Ophiocordyceps unilateralis (Tul.) Petch (1931) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Torrubia unilateralis Tul. (1865) | |

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis and related species are known to engage in an active secondary metabolism, among other reasons, for the production of substances active as antibacterial agents that protect the fungus-host ecosystem against further pathogenesis during fungal reproduction. Because of this secondary metabolism, an interest in the species has been taken by natural products chemists, with corresponding discovery of small molecule agents (e.g. of the polyketide family) of potential interest for use as human immunomodulatory, anti-infective, and anticancer agents.

Systematics

After years of research, the taxonomy of Ophiocordyceps unilateralis is becoming increasingly clear.

Cordyceps vs Ophiocordyceps

Throughout history there has been confusion about the distinction between both the Cordyceps genus and the Ophiocordyceps genus. These genera are different, however they were at the source of many debates about whether the zombie-ant fungus (and other fungi) belonged to one or to the other as Ophiocordyceps was only recently brought forward.

The Cordyceps genus comprises over 400 species, historically classified in the Clavicipitaceae family within the order Hypocreales. The classification was based on different morphological characteristics such as filiform ascospores and cylindrical asci.[3] When Cordyceps were first classified, there was no concrete evidence for the Ophiocordyceps genus. However, in 2007, important new molecular data was tested, and enabled them to re-classify the Clavicipitaceae family. It was found that Clavicipitaceae was in fact three distinct monophyletic families: the Clavicipitaceae, the Cordycipitaceae and the Ophiocordycipitaceae.[3]

The new molecular phylogenetics studies contradicted the older classification and moved all Cordyceps species forming a sister group with Tolypocladium, into Ophiocordycipitaceae. Fungi able to parasitize ants were also included in the transfer, such as Cordyceps unilateralis which was later renamed Ophiocordyceps unilateralis.[4] Following this study, multiple traits such as the production of darkly pigmented, hard to flexible stromata were defined as characteristics of the Ophiocordycipitaceae family.[4]

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis sensu lato

The fungus’ scientific name is sometimes written as Ophiocordyceps unilateralis sensu lato, which means “in the broad sense”, because the species actually represents a complex of many species within O. unilateralis.[5]

Support for this term has become increasingly important. In 2011, it was hypothesized that the zombie-ant fungus could actually be described as a complex of species which are host-specific, meaning that one O. unilateralis species can only successfully infect and manipulate one host ant species.[2] There is a possibility that this resulted in or re-inforced the reproductive isolation of the fungi, leading to its speciation. Following this, a study conducted in Brazil delimited using morphological comparison of the ascospores, germination process and asexual morphs, four different Ophiocordyceps species. Afterwards, three new species were described in the Brazilian Amazon, six in Thailand, and one in Japan.[6]

More recently in 2018, 15 new O. unilateralis species were described based on classic taxonomic criteria, and macro-morphological data with a deeper focus on ascospore and asexual morphology. The asexual morphologies enabled to distinguish two different clades mainly composed of species associated with ants which they termed “O. unilateralis core clade” and “O. kniphofioides sub-clade”.[4]

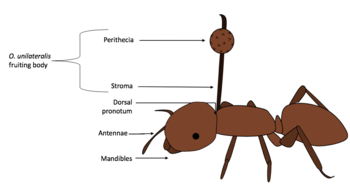

Further analyses were conducted using a set of different traits. Morphological traits were used and included both macro-morphological characters (e.g. typical single stroma arising from the host’s dorsal pronotum, the ascoma (perithecia) growing from the storm) and microscopic traits (e.g. the morphology of the ascospores in terms of size, shape, septation and germination). Moreover, other traits such as the host and the location of the death grip were added to the analyses.[4] The morphological study led to 15 new identified species, with 14 which were distributed in the core clade, and one in the sub-clade. Moreover, it was found that species in the O. kniphofioides sub-clade specialise on neotropical ants, whereas species in the core clade specialise on Camponotini species.[4]

Species within the O. unilateralis core clade as described in 2018[4]:

- O. albacongiuae

- O. blakebarnesii

- O. camponoti-atricipis

- O. camponoti-balzani

- O. camponoti-bispinosi

- O. camponoti-chartificis

- O. camponoti-femorati

- O. camponoti-floridani

- O. camponoti-hippocrepidis

- O. camponoti-indiani

- O. camponoti-leonardi

- O. camponoti- melanotic

- O. camponoti-nidulantis

- O. camponoti-novogranadensis

- O. camponoti-renggeri

- O. camponoti-saundersi

- O. halabalaensis

- O. kimflemingiae

- O. naomipierceae

- O. ootakii

- O. polyrhachis-furcata

- O. pulvinata

- O. rami

- O. satoi

Species within the O. kniphofioides sub-clade as described in 2018[4]:

- O. daceti

- O. kniphofioides

Morphology

Typical morphology

The zombie-ant fungus is easily identifiable when its reproductive structure becomes apparent on its dead host, usually a carpenter ant. At the end of its life cycle, O. unilateralis typically generates a single, wiry yet pliant, darkly pigmented stroma which arises from the dorsal pronotum region of the ant once it is dead.[7] Moreover, perithecia, the spore-bearing sexual structure, can be observed on the stalk, just below its tip.[3] This complex forms the fungus’ fruiting body.

Most species within the O. unilateralis s.l. species complex have both a sexual (teleomorph) and an asexual morph (anamorph). These are different in terms of their function and characteristics. Generally, the asexual morphs identified for Ophiocordyceps are Hirsutella and Hymenostilbe, two genera of asexually reproducing fungi.[7]

Morphological variation

O. unilateralis species exhibit morphological variations which are most certainly due to their wide geographic range, from Japan to the Americas. Moreover, it has been hypothesized that their morphological variations may also be a result of one fungus species maximizing its infection on one specific host ant species (host-specific infections). Different subspecies of ant can occur within the same area, which means that in order to coexist they have to occupy different ecological niches. Consequently, the fungi may have evolved at the subspecies level in order to maximize its fitness.[6]

O. unilateralis core clade morphological characteristics

The O. unilateralis core clade, as described in 2018, has distinct morphological characteristics. It exhibits a single stroma with a Hirsutella asexual morph, which arises from the dorsal neck region of the dead ant and produces a dark brown perithecia attached to its stalk.[4] These species are also recognizable through the host species they infect, which are only Camponotini species. Once the host is killed by the fungus, it is commonly found fixed through their mandibles onto the surfaces of leaves.[4]

O. kniphofioides sub-clade morphological characteristics

The O. kniphofioides sub-clade, as described in 2018, also has distinct morphological characteristics. Its species produce a stroma that grows laterally from the host’s thorax which itself generates an orange ascoma. Moreover, species within this sub-clade share a Hirsutella asexual morph.[4] As for the core clade, these species are also recognizable through the hosts they infect, which are usually neotropical ant species. The sub-clade does not present the same extended phenotype with the famous “death grip” that O. unilateralis species typically exhibit. Their hosts usually die at the base of large trees in the Amazonian rainforest, among the moss carpets.[4]

Life cycle

In tropical forests, the Camponotus leonardi species of ant lives in the high canopy and has an extensive network of aerial trails. Sometimes the canopy gaps are too difficult to cross, so the ants' trails descend to the forest floor where they are exposed to O. unilateralis spores. The spores attach to their exoskeletons and eventually break through using mechanical pressure and enzymes.[7] Like other fungi pathogenic to insects in the genus Ophiocordyceps, the fungus targets a specific host species, Camponotus leonardi; despite this, the fungus may parasitize other closely related species of ants with lesser degrees of host manipulation and reproductive success.[8]

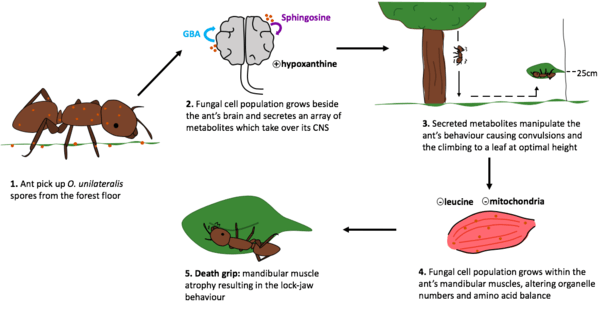

Yeast stages of the fungus spread in the ant's body and presumably produce compounds that affect the ant's hemocoel, using the evolutionary trait of an extended phenotype to manipulate the behavioral patterns exhibited by the ant.[9] An infected ant exhibits irregularly timed full-body convulsions that dislodge it from its canopy nest to the forest floor.[10]

The changes in the behavior of the infected ants are very specific, giving rise to the popular term "zombie ants". Behaviors are tuned for the benefit of the fungus in terms of its growth and its transmission, thereby increasing its fitness. The ant climbs up the stem of a plant and uses its mandibles with abnormal force to secure itself to a leaf vein, leaving dumbbell-shaped marks on it. The ants generally clamp to a leaf's vein at a height of 26 cm above the forest floor,[9] on the northern side of the plant, in an environment with 94–95% humidity and temperatures between 20 and 30 °C (68 and 86 °F). Infections may lead to 20 to 30 dead ants per square meter.[11] "Each time, they are on leaves that are a particular height off the ground and they have bitten into the main vein [of a leaf] before dying."[8] When the dead ants are moved to other places and positions, further vegetative growth and sporulation either fails to occur or results in undersized and abnormal reproductive structures.[9] In temperate forests, the stereotypical behaviour of zombie ants is to attach themselves to the lower side of twigs, not leaves.[12]

A search of plant-fossil databases revealed similar marks on a fossil leaf from the Messel Pit, which is 48 million years old.[13][14] Once the mandibles of the ant are secured to the leaf vein, atrophy quickly sets in, destroying the sarcomere connections in the muscle fibers and reducing the mitochondria and sarcoplasmic reticular. The ant is no longer able to control the muscles of the mandible and remains fixed in place, hanging upside-down on the leaf. This lockjaw trait is popularly known as the death grip and is essential in the fungus's lifecycle.[10] A study led in Thailand revealed that there is a synchronization of this manipulated biting behavior at solar noon.[12]

The fungus then kills the ant and continues to grow as its hyphae invade more soft tissues and structurally fortify the ant's exoskeleton.[8] More mycelia then sprout out of the ant, securely anchoring it to the plant substrate while secreting antimicrobials to ward off competition.[8] When the fungus is ready to reproduce, its fruiting bodies grow from the ant's head and rupture, releasing the spores. This process takes 4-10 days.[8] Dead ants are found in areas termed “graveyards” which contain high densities of dead ants previously infected by the same fungus.[15]

Natural products

O. unilateralis’ life cycle includes and depends on the infection and the manipulation of a carpenter ant, principally C. leonardi.[2] The behavioral manipulation of the ant, which gives rise to the name “zombie-ant”, is an extended phenotype of the fungus. It first affects the ant’s behavior through convulsions that make it fall from its high canopy nest onto the forest floor.[10] This is followed by the fungus controlling the climbing of the ant and the locking of its jaw (and subsequent death) onto a leaf around 25 centimetres above the ground, which is thought to be the optimal height for fungal spore growth and dispersion.[10]

Throughout the lifecycle, unique challenges must be met by equally unique metabolic activities. The fungal pathogen must attach securely to the arthropod exoskeleton and penetrate it—avoiding or suppressing host defenses—then, control the behavior of the host before killing it; and finally, it must protect the carcass from microbial and scavenger attack.[7]

The behavioral manipulation of the ant would not be possible without the presence of huge fungal cell populations beside the host’s brain[12] and within muscles[16] because these lead to the secretion of various metabolites known to have important behavioral consequences.[17] During the infection the parasite comes across an array of environments such as different host tissues or the immune response.[17] Studies have shown that O. unilateralis reacts heterogeneously by secreting different metabolites according to the host tissue it encounters and whether they are live or dead.[16] The identification of these natural products is important in order to understand which aspects of the ants are under control and consequently how O. unilateralis manipulates the ant.

- Attachment O. unilateralis spores onto the ant’s exoskeleton

The first step O. unilateralis has to overcome to have a successful infection, is to attach itself onto the ant’s cuticle and then infiltrate it. For this purpose, the fungus’ hypha pierces the exoskeleton using enzymes such as chitinase, lipase and protease, combined with mechanical pressure.[7]

- Convulsions and climbing behaviour

After the fungus enters the ant it propagates, and fungal cells can be found beside the host’s brain. Once the population is of sufficient size, the fungus secretes compounds and takes over the central nervous system (CNS), which enables it to manipulate the ant to reach the forest floor and climb up the vegetation.[12]

Two candidate compounds, sphingosine and guanidinobutyric acid (GBA), were identified as responsible for the manipulation of the host brain. Both of these metabolites are known in the scientific world to be involved in neurological disorders. However, more research is needed in the field to determine whether other fungal metabolites interact with the host brain and cause higher levels of sphingosine and GBA in the brain.[12]

Some studies identified another compound, hypoxanthine, present at high extracellular concentration. Hypoxanthine has deleterious effects on neural tissues of the cerebral cortex, which in the context of zombie ants may indicate a way for the fungus to alter the motor neurons of the ant, consequently affecting its behavior.[16]

- Death grip

The famous “death grip” exhibited by the ant is also a result of the fungus-induced manipulation. The behavior consists in the ant biting the leaf so tightly that the ant is prevented from falling as it dies hanging upside down, consequently enabling the proper growth of the fungus’ fruiting body.[17]

This is possibly a result of the atrophication of the ant’s mandibular muscles caused by the secretion of fungal compounds. In multiple studies, fungal cell populations were found within atrophied mandibular muscle tissues. In fact, they infiltrate between the muscle fibers and it is a common hypothesis of researchers that they cause the muscles’ atrophication the secretion of chemicals.[16] Significant decreases in leucine concentration and mitochondria number were identified in infected ants. A deficit in leucine results in the prevention of muscle regeneration because the amino acid is a nutrient regulator of muscle protein synthesis. A decrease in mitochondria ultimately results in a reduction of energy and calcium levels due to the lack of ATP and sarcoplasmic reticulum which provides calcium for actin-myosin binding which is essential for muscle cells.[16]

More in depth research is needed for the identification of other fungal compounds which act to atrophy the mandibular muscles, and for the understanding of their exact effects on the ant.

Natural products are host specific

Effects of O. unilateralis on host have been found to vary according to host species. The ant species which are normally found infected in nature exhibit a manipulated behavior, whereas the species which are not typically infected are killed by the infection, but their behaviour is not altered. This is likely due to the heterogeneous nature of the fungus which secretes different metabolites according to host species.[12]

Geographic distribution

Many studies describe Ophiocordyceps unilateralis distribution as pantropical since it occurs mainly in tropical forest ecosystems[5]. However, there are some reports of the zombie-ant fungus in warm-temperate ecosystems.[12]

Its distribution includes tropical rainforests located in Brazil, Australia and Thailand, and temperate forests found in South Carolina, Florida and Japan[4].

Host impact

O. unilateralis has been known to destroy entire ant colonies.[18][3] When O. unilateralis-infected ants die, they are mainly located in regions containing a high density of ants which were previously manipulated and killed.[15] These areas are termed “graveyards” and can be of 20 to 30 meters in range[18] (with a local density of dead ants possibly exceeding 25 meters square).[10]

The density of dead ants within these graveyards can vary according to climatic conditions. This means that environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature can influence O.unilateralis’ effects on the host population.[18] In fact, studies have described seasonal patterns in the density of previously-infected dead ants, with an increase during the rainy season and a decrease during the dry season.[2] It is thought that large precipitation events at the beginning and the end of the rainy season stimulates fungal development[2], which leads to more spores being released and ultimately more individuals being infected and killed.

Medicinal potential

Ophiocordyceps are known in the pharmaceutical world to be a medically-important group.[6] O. unilateralis fungi produce various known secondary metabolites, as well as several structurally uncharacterised substances. These natural products are reportedly being investigated as potential leads in discovery efforts toward immunomodulatory, antitumor, hypoglycemic, and hypocholesterolemic targets.[19]

In an Ophiocordyceps species within Japanese cicadas, the Ophiocordyceps replaces the symbiotic bacteria within the cicadas to help the host process sap as nutrients, unlike other related species, such as the Ophiocordyceps sinensis, which is a traditional immune booster and cancer treatment in Tibetan and Chinese culture.

Naphthoquinone derivatives

Naphthoquinone derivatives are an example of secondary metabolite with important pharmaceutical potentials produced by O. unilateralis. Six known naphthoquinone derivatives have been isolated from O. unilateralis, namely erythrostominone, deoxyerythrostominone, 4-O-methyl erythrostominone, epierythrostominol, deoxyerythrostominol, and 3,5,8-trihydroxy-6-methoxy-2-(5-oxohexa-1,3-dienyl)-1,4-naphthoquinone, which have shown activity in in vitro assays related to antimalarial drug discovery.[20][21] In addition to having antimalarial activities, all six of these secondary metabolites have been demonstrated to have anticancer and antibacterial activities.[22]

Moreover, the use of red naphthoquinone pigments produced by O. unilateralis has been studied as a dye for food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical manufacturing processes.[23] In fact, naphthoquinone derivatives produced by the fungus show a red color under acidic conditions, and a purple color under basic conditions. These pigments are stable against acid/alkaline conditions and light and are not cytotoxic, which makes them applicable for food coloring and as a dye for other materials. These attributes also make it a prime candidate for antituberculosis testing in secondary TB patients, by improving symptoms and enhancing immunity when combined with chemotherapeutic drugs.[24][25]

Polyketides

In 2009, a study showed that O. unilateralis also produces polyketides. These secondary metabolites have been used in antibiotics such as patulin, cholesterol medication such as compactin, and antifungal treatments. It has also been reported that polyketides have other therapeutic effects such as antitumor, antioxidant and antiaging activities.[26]

Fungal hyperparasite

O. unilateralis suffers from an unidentified fungal hyperparasite, reported in the lay press as the "antizombie-fungus fungus", that results in only 6–7% of sporangia being viable, limiting the damage O. unilateralis inflicts on ant colonies. The hyperparasite moves in to attack O. unilateralis as the fungal stalk emerges from the ant's body, which can stop the stalk from releasing its spores.[27][28]

The graveyards of dead ants are numerous and spread throughout the surrounding area of the colony. Though O. unilateralis is very virulent, only about 6.5% of all fruiting bodies are viable spore producers. This is caused by the weakening of the fungus by the hyperparasite, which may limit the viability of infectious spores. Ants also groom each other to combat microscopic organisms that could potentially harm the colony. Additional fungi grant beneficial assistance to the colony, as well.[28]

Parasite adaptation

In host-parasite dynamics, both the host and the parasite are under selective pressure: the parasite evolves to increase its transmission, whereas the host evolves to avoid and/or resist the infection by the parasite.

Extended phenotype

Some parasites have evolved to manipulate their host’s behavior in order to increase their transmission to uninfected susceptible individuals, thereby increasing their fitness.[18] This host manipulation is termed the "extended phenotype" of the parasite and is a form of adaptation. Host ant manipulation by O. unilateralis represents one of the best-known examples of extended phenotypes.[10]

The extended phenotype of O. unilateralis typically depicts the infected ant leaving its canopy nest and its normal foraging path to reach the forest floor and subsequently climb up 25cm above ground level. This height is considered to be optimal for fungal growth due to its humidity level and temperature. This is followed by a “death grip” of the infected ant once at what is considered to be the optimal conditions for post-mortem fungal development. This leads to the fungus continuing its growth and releasing fungal spores onto the forest floor.[17] These spores will then be encountered by the ants which, when the aerial foraging route is not possible, have to occasionally descend to ground level.[18] Therefore, O. unilateralis controls the ant's behaviour and this manipulation represents an adaptation for the fungus where natural selection acts on its genes with the purpose of increasing the fungus' fitness.[17]

Somatic investment

Some studies proposed a theory in which O. unilateralis has another possible form of adaptation which ensures its repeated reproduction. This would be crucial for O. unilateralis s.l. species as they can produce and release within the air, clear and thin-walled spores which are susceptible to environmental conditions such as UV radiation and dryness.[28]

In fact, studies suggest that the short viability of the fungal spores lead to the need of somatic investment (growth/survival) by the parasite in order to sustain the growth of the fungus’ fruiting body on its host, thereby enabling successive reproduction. To do so, O. unilateralis fortifies the ant cadaver to prevent its decay, which consequently ensures the growth of the fruiting body. Therefore, the zombie-ant fungus adapts to the short viability of its spores by increasing their production using the dead ant.[28]

Host adaptation

The principal hosts of O. unilateralis evolved adaptive behaviours able to limit the contact rate between uninfected susceptible hosts and infected hosts, thereby reducing the risk of transmission.

O.unilateralis’ principal hosts evolved efficient behavioral forms of social immunity. In fact, the ants clean the exoskeletons of one another in order to decrease the presence of spores which are attached to their cuticle.[10] Also, ants can sense that a member of the colony is infected; resulting in healthy ants carrying the O. unilateralis-infected individual far away from the colony to avoid fungal spore exposure. Plus, there are reports testifying that most worker ants remain inside the nest boundaries, consequently, only foragers are at risk of infection.[28]

Moreover, one of the fungus' principal hosts, Camponotus leonardi, provided evidence for the avoidance of the forest floor by the host ants as a defence method.[18] In areas where O. unilateralis is present, C. leonardi builds its nests high in the canopy, and has a broad network of areal trails. These trails occasionally move down to the ground level, where infection and graveyards occur, due to canopy gaps too difficult for the ants to cross. When the trails descend to the forest floor, their length is only of three to five meters before going back up into the canopy. This demonstrates the avoidance of the zones of infection by the ants. Additionally, more evidence participates in the favour of this defence method being adaptive as it is not observed in undisturbed forests where the zombie-ant fungus is not present.[18]

References

- "Ophiocordyceps unilateralis". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- Mongkolsamrit S, Kobmoo N, Tasanathai K, Khonsanit A, Noisripoom W, Srikitikulchai P, et al. (November 2012). "Life cycle, host range and temporal variation of Ophiocordyceps unilateralis/Hirsutella formicarum on Formicine ants". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 111 (3): 217–24. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2012.08.007. PMID 22959811.

- Sung GH, Hywel-Jones NL, Sung JM, Luangsa-Ard JJ, Shrestha B, Spatafora JW (2007). "Phylogenetic classification of Cordyceps and the clavicipitaceous fungi". Studies in Mycology. 57 (1): 5–59. doi:10.3114/sim.2007.57.01. PMC 2104736. PMID 18490993.

- Araújo JP, Evans HC, Kepler R, Hughes DP (June 2018). "Ophiocordyceps. I. Myrmecophilous hirsutelloid species". Studies in Mycology. 90: 119–160. doi:10.1016/j.simyco.2017.12.002. PMC 6002356. PMID 29910522.

- Evans HC, Elliot SL, Hughes DP (March 2011). "Hidden diversity behind the zombie-ant fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis: four new species described from carpenter ants in Minas Gerais, Brazil". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17024. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617024E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017024. PMC 3047535. PMID 21399679.

- Evans HC, Araújo JP, Halfeld VR, Hughes DP (June 2018). "Ophiocordycipitaceae)". Fungal Systematics and Evolution. 1: 13–22. doi:10.3114/fuse.2018.01.02. PMC 7274273. PMID 32518897.

- Evans HC, Elliot SL, Hughes DP (September 2011). "Ophiocordyceps unilateralis: A keystone species for unraveling ecosystem functioning and biodiversity of fungi in tropical forests?". Communicative & Integrative Biology. 4 (5): 598–602. doi:10.4161/cib.16721. PMC 3204140. PMID 22046474.

- Sample I (18 August 2010). "'Zombie ants' controlled by parasitic fungus for 48m years". News » Science » Microbiology. The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- Andersen SB, Gerritsma S, Yusah KM, Mayntz D, Hywel-Jones NL, Billen J, et al. (September 2009). "The life of a dead ant: the expression of an adaptive extended phenotype". The American Naturalist. 174 (3): 424–33. doi:10.1086/603640. JSTOR 10.1086/603640. PMID 19627240.

- Hughes DP, Andersen SB, Hywel-Jones NL, Himaman W, Billen J, Boomsma JJ (May 2011). "Behavioral mechanisms and morphological symptoms of zombie ants dying from fungal infection". BMC Ecology. 11 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-11-13. PMC 3118224. PMID 21554670.

- Attenborough D (3 November 2008). "Cordyceps: attack of the killer fungi". Planet Earth. BBC Worldwide. Retrieved 2013-04-21.

- de Bekker C, Quevillon LE, Smith PB, Fleming KR, Ghosh D, Patterson AD, Hughes DP (August 2014). "Species-specific ant brain manipulation by a specialized fungal parasite". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 14 (1): 166. doi:10.1186/s12862-014-0166-3. PMC 4174324. PMID 25085339.

- "Fossil Reveals 48-Million-Year History of Zombie Ants". Science Daily. 18 August 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- Hughes DP, Wappler T, Labandeira CC (February 2011) [18 August 2010]. "Ancient death-grip leaf scars reveal ant-fungal parasitism". Biology Letters. 7 (1): 67–70. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0521. PMC 3030878. PMID 20719770.

- Sobczak JF (2017). "The zombie ants parasitized by the fungi Ophiocordyceps camponotiatricipis (Hypocreales: Ophiocordycipitaceae): new occurrence and natural history". Mycosphere. 8 (9): 1261–1266. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/8/9/1.

- Zheng S, Loreto R, Smith P, Patterson A, Hughes D, Wang L (September 2019). "Specialist and Generalist Fungal Parasites Induce Distinct Biochemical Changes in the Mandible Muscles of Their Host". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (18): 4589. doi:10.3390/ijms20184589. PMC 6769763. PMID 31533250.

- de Bekker C, Merrow M, Hughes DP (July 2014). "From behavior to mechanisms: an integrative approach to the manipulation by a parasitic fungus (Ophiocordyceps unilateralis s.l.) of its host ants (Camponotus spp.)". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 54 (2): 166–76. doi:10.1093/icb/icu063. PMID 24907198.

- Pontoppidan MB, Himaman W, Hywel-Jones NL, Boomsma JJ, Hughes DP (12 March 2009). "Graveyards on the move: the spatio-temporal distribution of dead ophiocordyceps-infected ants". PLOS ONE. 4 (3): e4835. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4835P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004835. PMC 2652714. PMID 19279680.

- Xiao JH, Zhong JJ (2007). "Secondary metabolites from Cordyceps species and their antitumor activity studies". Recent Patents on Biotechnology. 1 (2): 123–37. doi:10.2174/187220807780809454. PMID 19075836.

- Kittakoopa P, Punyaa J, Kongsaeree P, Lertwerawat Y, Jintasirikul A, Tanticharoena M, Thebtaranonth Y (1999). "Bioactive naphthoquinones from Cordyceps unilateralis". Phytochemistry. 52 (3): 453–457. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00272-1.

- Wongsa P, Tasanatai K, Watts P, Hywel-Jones N (August 2005). "Isolation and in vitro cultivation of the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps unilateralis". Mycological Research. 109 (Pt 8): 936–40. doi:10.1017/S0953756205003321. PMID 16175796.

- Amnuaykanjanasin A, Panchanawaporn S, Chutrakul C, Tanticharoen M (August 2011). "Genes differentially expressed under naphthoquinone-producing conditions in the entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis". Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 57 (8): 680–92. doi:10.1139/W11-043. PMID 21823977.

- Unagul P, Wongsa P, Kittakoop P, Intamas S, Srikitikulchai P, Tanticharoen M (April 2005). "Production of red pigments by the insect pathogenic fungus Cordyceps unilateralis BCC 1869". Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology. 32 (4): 135–40. doi:10.1007/s10295-005-0213-6. PMID 15891934. S2CID 22937549.

- Isaka M, Kittakoop P, Kirtikara K, Hywel-Jones NL, Thebtaranonth Y (October 2005). "Bioactive substances from insect pathogenic fungi". Accounts of Chemical Research. 38 (10): 813–23. doi:10.1021/ar040247r. PMID 16231877.

- Wang Y, Enlai DA, Zhong JI (2013). "A Retrospective Analysis of Cordyceps Anti-Tuberculosis Capsule Combined with Chemotherapy for 614 Cases of Secondary Tuberculosis". Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 15.

- Amnuaykanjanasin A, Phonghanpot S, Sengpanich N, Cheevadhanarak S, Tanticharoen M (June 2009). "Insect-specific polyketide synthases (PKSs), potential PKS-nonribosomal peptide synthetase hybrids, and novel PKS clades in tropical fungi". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 75 (11): 3721–32. doi:10.1128/AEM.02744-08. PMC 2687288. PMID 19346345.

- "The Zombie-Ant Fungus Is Under Attack, Research Reveals". Pennsylvania State University. 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2013-03-04.

- Andersen SB, Ferrari M, Evans HC, Elliot SL, Boomsma JJ, Hughes DP (2 May 2012). "Disease dynamics in a specialized parasite of ant societies". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e36352. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736352A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036352. PMC 3342268. PMID 22567151.

Further reading

- de Bekker C, Ohm RA, Loreto RG, Sebastian A, Albert I, Merrow M, Brachmann A, Hughes DP (August 2015). "Gene expression during zombie ant biting behavior reflects the complexity underlying fungal parasitic behavioral manipulation". BMC Genomics. 16: 620. doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1812-x. PMC 4545319. PMID 26285697.

- Will I, Das B, Trinh T, Brachmann A, Ohm RA, de Bekker C (July 2020). "Genetic Underpinnings of Host Manipulation by Ophiocordyceps as Revealed by Comparative Transcriptomics". G3 (Bethesda, Md.). 10 (7): 2275–2296. doi:10.1534/g3.120.401290. PMC 7341126. PMID 32354705.

- Fredericksen MA, Zhang Y, Hazen ML, Loreto RG, Mangold CA, Chen DZ, Hughes DP (November 2017). "Three-dimensional visualization and a deep-learning model reveal complex fungal parasite networks in behaviorally manipulated ants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (47): 12590–12595. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711673114. PMC 5703306. PMID 29114054.

- Lin YC, Hsu JY, Shu JH, Chi Y, Chiang SC, Lee ST (November 2008). "Two distinct arsenite-resistant variants of Leishmania amazonensis take different routes to achieve resistance as revealed by comparative transcriptomics". Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 162 (1): 16–31. doi:10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.06.015. PMID 18674569.

- Sheldrake M (2020). Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures. ISBN 978-0-525-51031-4.

External links

- Ophiocordyceps unilateralis at UniProt.org. Accessed on 2010-08-22.

- An Electronic Monograph of Cordyceps and Related Fungi