Operation Turkey Buzzard

Operation Turkey Buzzard, also known as Operation Beggar, was a British supply mission to North Africa that took place between March and August 1943, during the Second World War. The mission was undertaken by No. 2 Wing, Glider Pilot Regiment and No. 295 Squadron Royal Air Force, prior to the Allied invasion of Sicily. Unusually, the mission was known by different names in different branches of the British Armed Forces: the British Army called the operation "Turkey Buzzard", while in the Royal Air Force it was known as "Beggar".[1]

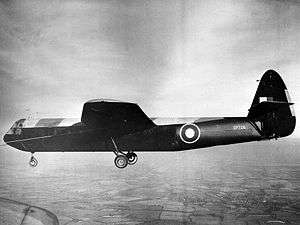

The mission involved Royal Air Force Handley Page Halifax bombers towing Airspeed Horsa gliders 3,200 miles (5,100 km) from England to Tunisia. The British Horsas were needed to complement the smaller American Waco gliders, which did not have the capacity required for the operations planned by the 1st Airborne Division.

During the mission one Halifax-and-Horsa combination was shot down by German Focke Wulf Condor long-range patrol aircraft. Altogether five Horsas and three Halifaxes were lost, but twenty-seven Horsas arrived in Tunisia in time to participate in the invasion of Sicily. Although this supply operation was a success, few of the gliders made it to their landing zones in Sicily during the two British airborne operations that followed, many becoming casualties of the weather conditions or anti-aircraft gunfire.

Background

By December 1942, with Allied forces advancing through Tunisia, the North African campaign was coming to a close; victory in North Africa being imminent, discussions began between the Allies over what their next objective should be.[2] Many Americans argued for an immediate invasion of France, while the British believed that it should be the island of Sardinia,[2] as did General Dwight D. Eisenhower.[3] In January 1943 the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and the President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, met at the Casablanca conference and settled the debate: the island of Sicily would be the Allies' next objective.[2] The invasion and occupation of Sicily would benefit the Allies by opening Mediterranean sea routes for Allied shipping and allowing Allied bombers to operate from airfields that were much closer to mainland Italy and Germany.[4] The codename Operation Husky was eventually decided on for the invasion, and planning began in February. The British Eighth Army, under the command of General Bernard Montgomery, would land on the south-eastern corner of the island and advance north to the port of Syracuse, while the US Seventh Army, commanded by General George Patton, would land on the south coast and move towards the port of Palermo on the western corner of the island.[2] The landings would be made simultaneously along a 100-mile (160-km) stretch of the island's south-eastern coastline.[5]

For their part, the 1st Airborne Division was to conduct three brigade-size airborne operations; the Ponte Grande road bridge south of Syracuse was to be captured by 1st Airlanding Brigade (Operation Ladbroke), the port of Augusta was to be seized by 2nd Parachute Brigade (Operation Glutton), and finally the Primasole Bridge over the River Simeto was to be taken by 1st Parachute Brigade (Operation Fustian).[6]

When the plans for the British airborne operations were being discussed, Lieutenant-Colonel George Chatterton, the commander of No. 2 Wing, Glider Pilot Regiment, brought up a problem with the only glider then in theatre, the American Waco CG-4, known in British service as the Hadrian: its small size. The Waco's capacity was only two pilots and thirteen troops, and for cargo either a jeep or an artillery gun but not both together.[7] The plan for Operation Ladbroke involved a coup de main assault on the Ponte Grande Bridge by the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment. Using the Horsa glider, which could carry twenty-seven troops or a jeep and gun together, they could deliver a larger force at the bridge during the initial assault.[8] Chatterton decided he needed around forty Horsas, as well as the American Wacos, for the British missions.[9]

Mission

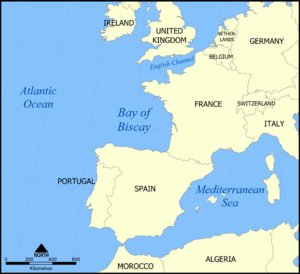

The only Horsa gliders were in England at the time, and transporting them to North Africa would require a tow of 1,200 miles (1,900 km) over the Atlantic Ocean around the coast of Portugal and Spain, then a further 2,000 miles (3,200 km) across North Africa to reach Tunisia.[10] No one had ever towed a glider that distance before, and it was not known if it was even possible. To test the concept and prove they had the necessary endurance, Handley Page Halifax bombers of No. 295 Squadron RAF towed Horsa gliders around the coastline of Britain.[9]

The mission was given the go-ahead; the Horsas were modified to jettison their landing gear after takeoff to reduce drag, while the Halifax bombers were modified with long-range fuel tanks fitted in the bomb bays.[7] The pilots for the gliders came from No. 2 Wing, having been left in England when most of the wing departed for Tunisia earlier in the year.[7] An eleven-week period of training followed, during which four crashes killed thirteen men.[11] At a mission conference on 21 May 1943, hosted by No. 38 Wing RAF, the impossibility of training the bomber crews to tow the gliders and deliver forty gliders to North Africa was discussed. In the end it was decided that as a priority ten bomber crews would be fully trained to deliver around fifteen gliders to North Africa by 21 June.[11]

The Halifaxes and Horsas were moved to RAF Portreath in Cornwall, to shorten the distance they would have to travel. Even so, they were left with a ten-hour flight to Sale airport in Morocco.[12] On arrival at Sale the gliders were released to land on a sand-patch alongside the runway. Once on the ground each Horsa was fitted with the spare landing gear it carried inside,[11] and the flight immediately took off again on the next leg of the journey, to Mascara in Algeria.[7] Their journey did not end here; they left for the final destination, Kairouan Airfield in Tunisia, as soon as possible.[12] During the flight the gliders were provided with three pilots, who had to change around every hour to relieve fatigue.[12]

The flights were carried out between 3 June and 7 July; the first Horsas arrived at Kairouran on 28 June, only twelve days before they were to be used in Operation Ladbroke.[13] During the flight from England, for its first three hours over the Bay of Biscay the Halifax–Horsa combination was escorted by RAF Bristol Beaufighters or Mosquito long-range fighter aircraft. They kept to an altitude of 500 ft (150 m) to avoid German radar so the escorting fighters could return safely when short of fuel.[7] The mission was not without its dangers. Four hours into one flight, a Horsa snapped its tow-rope while trying to avoid low cloud and ditched in the sea.[12] Another Horsa and Halifax were discovered by a pair of German Focke-Wulf Fw 200s and shot down.[14] After surviving attacks from Luftwaffe fighter patrols and experiencing often-turbulent weather, a total of twenty-seven Horsas were delivered to North Africa in time for the invasion of Sicily.[15] The total losses during the flights were three Halifaxes and five Horsas,[14] with twenty-one RAF aircrew and seven glider pilots killed.[7][16]

Aftermath

The first British airborne operation in Sicily began at 18:00 on 9 July 1943, when the gliders transporting the 1st Airlanding Brigade left Tunisia for Sicily.[17] En route they encountered strong winds and poor visibility, and at times were subjected to anti-aircraft fire.[17] To avoid gunfire and searchlights, pilots of the towing aircraft climbed higher or took evasive action. In the confusion surrounding these manoeuvres, some gliders were released too early and sixty-five of them crashed into the sea, drowning around 252 men.[17] Fifty-nine of the remaining gliders missed their landing zones, by as much as 25 miles (40 km); others either failed to release and returned to Tunisia or were shot down.[17] Only twelve landed on target; of these gliders a single Horsa, carrying a platoon of infantry from the Staffords, landed near the Ponte Grande Bridge. Its commander, Lieutenant Withers, swam across the river with half his men to take up positions on the opposite bank. The objective was captured following a simultaneous assault from both ends;[18] the platoon then dismantled demolition charges that had been fitted to the bridge, and dug in to wait for reinforcement or relief.[18] Another Horsa came down about 200 yards (180 m) from the bridge but exploded on landing, killing all on board. Three of the other Horsas carrying the South Staffordshire Regiment coup-de-main party had landed within 2 miles (3.2 km) of the bridge, their occupants eventually finding their way to the site.[19]

The second and last mission—Operation Fustian—began at 19:30 on 12 July, when the first aircraft carrying the 1st Parachute Brigade took off from North Africa.[20][21] Following behind the parachute force were the glider-towing aircraft, comprising twelve Albemarles and seven Halifaxes, towing eleven Horsa and eight Waco gliders.[22] The first glider casualties occurred on takeoff, when two aircraft towing Waco gliders crashed.[23] While en route, one glider was released prematurely by its towing aircraft and crashed into the sea. Arriving over Sicily, having lost the element of surprise, four gliders were shot down by coastal anti-aircraft batteries.[23] By the time the gliders arrived at their landing zones, two hours had lapsed since the start of the parachute landings.[24] With the German defences alerted, only four Horsa gliders managed to land mostly intact, all the others being caught by German machine-gun fire and destroyed on their approach. The surviving Horsas had been carrying three of the brigade's anti-tank guns, which were now included in their defence of Primosole Bridge.[25][26]

Notes

- Peters, Mike. "Staff Sergeant Mike Hall's experience of Operation Turkey-Buzzard and exercises prior to the invasion of Sicily". Paradata. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

The RAF codenamed the glider delivery mission as Operation Beggar, the GPR came up with the very apt ‘Operation Turkey-Buzzard’.

- Warren, p.21

- Eisenhower, p.159

- Eisenhower, p.60

- Harclerode, p.275

- Harclerode, p.256

- Smith, p.47

- Shannon, p.201

- Peters, p.12

- Seth, p.77

- Smith, p.48

- Naughton, Philippe; Costello, Miles. "Obituary Denis Hall". The Times. London. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Smith, pp.47–48

- "Obituary Tommy Grant". Daily Telegraph. London. 7 September 2000. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Lloyd, pp.43–44

- Smith, p.153

- Mitcham, pp.73–74

- Mitcham, p.74

- Tugwell, p.160

- Mitcham, p.148

- Cole, p.45

- Mrazek, p.82

- Mrazek, p.84

- Mitcham, p.150

- Reynolds, p.37

- Mitcham, p.153

References

- Cole, Howard N (1963). On Wings of Healing: the Story of the Airborne Medical Services 1940-1960. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: William Blackwood. OCLC 29847628.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1948). Crusade in Europe. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-41619-9.

- Harclerode, Peter (2005). Wings Of War – Airborne Warfare 1918–1945. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-304-36730-3.

- Huston, James A. (1998). Out Of The Blue – U.S Army Airborne Operations In World War II. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-148-X.

- Lloyd, Alan (1982). The Gliders: The story of Britain's fighting gliders and the men who flew them. Ealing, United Kingdom: Corgi. ISBN 0-552-12167-3.

- Mitcham, Samuel W; Von Stauffenberg, Friedrich (2007). The Battle of Sicily: How the Allies Lost Their Chance for Total Victory. Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3403-X.

- Mrazek, James (2011). Airborne Combat: Axis and Allied Glider Operations in World War II. Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0808-X.

- Peters, Mike; Luuk, Buist (2009). Glider Pilots at Arnhem. Barnsley, England: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 1-84415-763-6.

- Seth, Ronald (1955). Lion with blue wings: the story of the Glider Pilot Regiment, 1942-1945. London: Gollancz. OCLC 7997514.

- Shannon, Kevin; Wright, Stephen (1994). One Night in June. Shrewsbury, United Kingdom: Airlife Publishing. ISBN 1-85310-492-2.

- Simons, Martin (1996). Slingsby Sailplanes. London: Airlife Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85310-732-8.

- Smith, Claude (2007). History of the Glider Pilot Regiment. Barnsley, United Kingdom: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-626-9.

- Warren, Dr John C. (1955). Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942–1945. Air University, Maxwell AFB: US Air Force Historical Research Agency. ISBN 0-7183-0262-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Beggar. |