Oirats

Oirats (Mongolian: Ойрад, Oirad, Mongolian pronunciation: [ɔiˈrɑt] or Ойрд, Oird; Kalmyk: Өөрд; in the past, also Eleuths)[1] are the westernmost group of the Mongols whose ancestral home is in the Altai region of Xinjiang and Western Mongolia.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 638,372 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(mainly in Xinjiang) | 250,000 (2013 estimate) |

| 205,000 (2010 census) | |

| 183,372 (2010 census) | |

| Languages | |

| Oirat, other Mongolian languages | |

| Religion | |

| Tibetan Buddhism, Shamanism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mongols, Tuvans, Kalmyks | |

Historically, the Oirats were composed of four major tribes: Dzungar (Choros or Olots), Torghut, Dörbet and Khoshut. The minor tribes include: Khoid, Bayads, Myangad, Zakhchin, Baatud.

Etymology

The name probably derives from Mongolic oi ("forest, woods") and ard < *harad ("people"),[2] and they were counted among the "forest people" in the 13th century.[3] Similar to that is the Turkic aghach ari ("woodman") that is found as place name in many locales, including the corrupted name of the town of Aghajari in Iran. A second opinion believes the name derives from Mongolian word oirt (or oirkhon) meaning "close (as in distance)," as in "close/nearer ones."

The name Oirat may derive from a corruption of the group's original name Dörben Öörd, meaning "The Allied Four". Perhaps inspired by the designation Dörben Öörd, other Mongols at times used the term "Döchin Mongols" for themselves ("Döchin" meaning forty), but there was rarely as great a degree of unity among larger numbers of tribes as among the Oirats.

These views are challenged by Kempf 2010, who from a historical linguist's point of view argues that the name is a plural coming from *oyiran, and eventually from Turkic *ōy 'a word for a colour of a horse’s coat' (oy + gir suffix for colours + (A)n collective suffix).

Writing system

In the 17th century, Zaya Pandita,[4] a Gelug monk of the Khoshut tribe, devised a new writing system called Clear Script for use by Oirats. This system was developed on the basis of the older Mongolian script, but had a more developed system of diacritics to preclude misreading and reflected some lexical and grammatical differences of the Oirat language from Mongolian.[5]

The Clear Script remained in use in Kalmykia until the mid-1920s when it was replaced by a Latin alphabet, and later the Cyrillic script. It can be seen in some public signs in the Kalmyk capital, Elista, and is superficially taught in schools. In Mongolia it was likewise replaced by the Cyrillic alphabet in 1941. Some Oirats in China still use the Clear Script as their primary writing system, as well as Mongolian script.

A monument of Zaya Pandita was unveiled on the 400th anniversary of Zaya Pandita's birth, and on 350th anniversary of his creation of the Clear Script.[6]

History

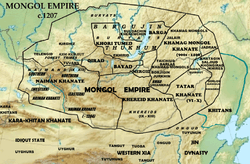

The Oirats share some history, geography, culture and language with the Eastern Mongols, and were at various times united under the same leader as a larger Mongol entity, whether that ruler was of Oirat descent or of Chingissids.

Comprising the Khoshut (Mongolian: "хошууд", hošuud), Choros or Ölöt ("өөлд", Ööld), Torghut ("торгууд", Torguud), and Dörbet ("дөрвөд", Dörvöd) ethnic groups, they were dubbed Kalmyk or Kalmak, which means "remnant" or "to remain", by their western Turkic neighbours. Various sources also list the Bargut, Buzava, Keraites, and Naiman tribes as comprising part of the Dörben Öörd; some tribes may have joined the original four only in later years. This name may however reflect the Kalmyks' remaining Buddhist rather than converting to Islam; or the Kalmyks' remaining in then Altay region when the Turkic tribes migrated further west.

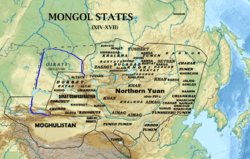

After the fall of the Yuan dynasty, Oirat and Eastern Mongols had developed separate identities to the point where Oirats called themselves "Four Oirats" while they used the term "Mongols" for those under the Khagans in the east.[7]

Early history

One of the earliest mentions of the Oirat people in a historical text can be found in The Secret History of the Mongols, the 13th century chronicle of Genghis Khan's rise to power. In the Secret History, the Oirats are counted among the "forest people" and are said to live under the rule of a shaman-chief known as bäki. They lived in Tuva and Mongolian Khövsgöl Province and the Oirats moved to the south in the 14th century.[8]

In one famous passage the Oirat chief, Quduqa Bäki, uses a yada or 'thunder stone' to unleash a powerful storm on Genghis' army. The magical ploy backfires however, when an unexpected wind blows the storm back at Quduqa. During early stages of Genghis's rise, Oirats under Quduqa bekhi fought against Genghis and were defeated. Oirats were fully submitted to Mongol rule after their ally Jamukha, Genghis's childhood friend and later rival, was destroyed. Subject to the khan Oirats would form themselves as a loyal and formidable faction of the Mongol war machine. In 1207, Jochi the eldest son of Genghis, subjugated the forest tribes including the Oirats and the Kyrgyzs. The Great Khan gave those people to his son, Jochi, and had one of his daughters, Checheygen, marry the Oirat chief Khutug-bekhi or his son. There were notable Oirats in the Mongol Empire such as Arghun Agha and his son Nowruz. In 1256, a body of the Oirats under Bukha-Temür (Mongolian: Буха-Төмөр, Бөхтөмөр) joined Hulagu's expedition to Iran and fought against Hashshashins, Abbasids in Persia. The Ilkhan Hulagu and his successor Abagha resettled them in Turkey. And they took part in the Second Battle of Homs where the Mongols were defeated.[9] The majority of the Oirats, who were left behind, supported Ariq Böke against Kublai in the Toluid Civil War. Kublai defeated his younger brother and they entered the service of the victor. In 1295, more than 10,000 Oirats under Targhai Khurgen (son-in-law of the Borjigin family) fled Syria, then under the Mamluks because they were despised by both Muslim Mongols and local Turks. They were well received by the Egyptian Sultan Al-Adil Kitbugha of Oirat origin.[10] Ali Pasha, who was the governor of Baghdad, head of an Oirat ruling family, killed Ilkhan Arpa Keun, resulting in the disintegration of Mongol Persia. Because the Oirats were near both the Chagatai Khanate and the Golden Horde, they had strong ties with them and many Mongol khans had Oirat wives.

After the expulsion of the Yuan dynasty from China, the Oirats forgathered as a loose alliance of the four major West Mongolian tribes (Mongolian: Dörben Oyirad, "дөрвөн ойрд", "дөрвөн ойрaд"). The alliance grew, taking power in the remote region of the Altai Mountains, northwest of Hami oasis. Gradually they spread eastwards, annexing territories then under the control of the Eastern Mongols, and hoping to reestablish a unified nomadic rule under their banner of the Four Oirats, made out of the Keraites, Naiman, Barghud, and old Oirats.[11][12]

The only Borjigid ruling tribe was the Khoshuts, while the others' rulers were not descendants of Genghis. The Ming Chinese had helped the Oirat's rise to power over the Mongols during the Yongle Emperor's reign after 1410 when the Ming defeated the Qubilaid Öljei Temür and the Borjigid power was weakened.[13] The Borjigid Khans were displaced from power by the Oirats with Ming help and only ruled as puppet khans until the alliance between Ming and Oirats ended and the Yongle Emperor launched a campaign against them.[14]

The greatest ruler of the Four Oirats was Esen Tayisi who led the Four Oirats from 1438 to 1454, during which time he unified Mongolia (both Inner and Outer) under his puppet khan Toghtoa Bukha. In 1449 Esen Tayisi and Toghtoa Bukh mobilized their cavalry along the Chinese border and invaded Ming China, defeating and destroying the Ming defences at the Great Wall and reinforcements sent to intercept his cavalry. In the process, the Zhengtong Emperor was captured at Tumu. The following year, Esen returned the emperor after an unsuccessful ransom attempt. After claiming the title of khan, to which only lineal descendants of Genghis Khan could claim, Esen was killed. Shortly afterwards, Oirat power declined.

From the 14th until the middle of the 18th century, the Oirats were often at war with the Eastern Mongols but were reunited with them during the rule of Dayan Khan and Tümen Zasagt Khan.

The Khoshut Khanate

The Oirats converted to Tibetan Buddhism around 1615, and it was not long before they became involved in the conflict between the Gelug and Karma Kagyu schools. At the request of the Gelug school, in 1637, Güshi Khan, the leader of the Khoshuts in Koko Nor, defeated Choghtu Khong Tayiji, the Khalkha prince who supported the Karma Kagyu school, and conquered Amdo (present-day Qinghai). The unification of Tibet followed in the early 1640s, with Güshi Khan proclaimed Khan of Tibet by the 5th Dalai Lama and the establishment of the Khoshut Khanate. The title "Dalai Lama" itself was bestowed upon the third lama of the Gelug tulku lineage by Altan Khan (not to be confused with the Altan Khans of the Khalkha), and means, in Mongolian, "Ocean of Wisdom".

Amdo, meanwhile, became home to the Khoshuts. In 1717, the Dzungars invaded Tibet and killed Lha-bzang Khan (or Khoshut Khan), a grandson of Güshi Khan and the fourth Khan of Tibet, conquered the Khoshut Khanate

The Qing Empire defeated the Dzungars in the 1750s and proclaimed the rule over Oirats through Manchu-Mongols-Alliance (a series of systematic arranged-marriages between princes and princesses of Manchu with those of Khalkha Mongols and Oirat Mongols, which was set up as a royal policy carried out over 300 years), as well as over Khoshut-controlled Tibet.

In 1723 Lobzang Danjin, another descendant of Güshi Khan, took control of Amdo and tried to assume rule over the Khoshut Khanate. He fought against a Manchu-Qing Dynasty army, and was defeated only in the following year and 80,000 people from his tribe were executed by Manchu army due to his "rebellion attempt".[15] By that period, Upper Mongolian population reached 200,000 and were mainly under the ruling of Khalkha Mongols princes who were in marriage alliance with Manchu royal and noble families. Thus, Amdo fell under Manchu domination.

The Dzungar Khanate

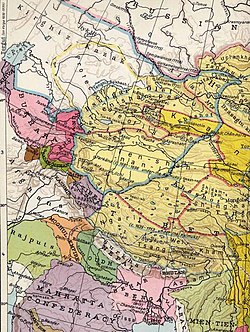

The 17th century saw the rise in power of another Oirat empire in the east, known as the Khanate of Dzungaria, which stretched from the Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan, and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia. It was the last empire of nomads, which was ruled by Choros noblemen.

The Qing (or Manchu) conquered China in the mid-17th century and sought to protect its northern border by continuing the divide-and-rule policy their Ming predecessors had successfully instituted against the Mongols. The Manchu consolidated their rule over the East Mongols of Manchuria. They then persuaded the East Mongols of Inner Mongolia to submit themselves as vassals. Finally, the East Mongols of Outer Mongolia sought the protection of the Manchu against the Dzungars.

Some scholars estimate that about 80% of the Dzungar population was wiped out by a combination of warfare and disease during the Manchu-Qing conquest of Dzungaria in 1755–1757.[16] The Zunghar population reached 600,000 in 1755.

The main population of the Choros, Olot, Khoid, Baatud, and Zakhchin Oirats who battled against the Qing were killed by the Manchu soldiers and after the fall of the Dzungar Khanate they became small ethnic groups. There were 600,000 Khalkha Mongols and 600,000 Oirats in 1755 and now approximately 2.3 million Khalkha and 640,000 Oirats live in four counties while a few hundred Choros people live in Mongolia.

Kalmyks

Kho Orlok, tayishi of the Torghuts, and Dalai Tayishi of Dorbets, led their people (200,000–250,000 people, mainly Torghuts) west to the (Volga River) in 1607 where they established the Kalmyk Khanate. By some accounts this move was precipitated by internal divisions or by the Khoshut tribe; other historians believe it more likely that the migrating clans were seeking pastureland for their herds, scarce in the Central Asian highlands. Part of the Khoshut and Ölöt tribes joined the migration almost a century later. The Kalmyk migration had reached as far as the steppes of southeast Europe by 1630. At the time, that area was inhabited by the Nogai Horde. But under pressure from Kalmyk warriors, the Nogais fled to the Crimea and the Kuban River. Many other nomadic peoples in the Eurasian steppes subsequently became vassals of the Kalmyk Khanate, part of which is in the area of present-day Kalmykia.[17]

The Kalmyks became allies of Russia and a treaty to protect southern Russian borders was signed between the Kalmyk Khanate and Russia. Later they became nominal, then full subjects of the Russian Tsar. In 1724 the Kalmyks came under control of Russia. By the early 18th century, there were approximately 300,000–350,000 Kalmyks and 15,000,000 Russians. Russia gradually chipped away the autonomy of the Kalmyk Khanate. These policies encouraged establishment of Russian and German settlements on pastures where the Kalmyks formerly roamed and fed their livestock. The Russian Orthodox church, by contrast, pressed Buddhist Kalmyks to adopt Orthodoxy. In January 1771 the oppression of czarist administration forced a larger part of Kalmyks (33,000 households or approximately 170,000 individuals) to migrate to Dzungaria.[18] 200,000 (170,000)[19] Kalmyks began the migration from their pastures on the left bank of the Volga River to Dzungaria, through the territories of their Bashkir and Kazakh enemies. The last Kalmyk khan Ubashi led the migration to restore the Dzungar Khanate and Mongolian independence.[19] As C. D. Barkman notes, "It is quite clear that the Torghuts had not intended to surrender to the Chinese, but had hoped to lead an independent existence in Dzungaria".[20] Ubashi Khan sent his 30,000 cavalry to the Russo-Turkish War in 1768–1769 to gain weapons before the migration. The Empress Catherine the Great ordered the Russian army, Bashkirs and Kazakhs to exterminate all migrants and Catherine the Great abolished the Kalmyk Khanate.[19][21][22] The Kyrgyzs attacked them near Balkhash Lake. About 100,000–150,000 Kalmyks who settled on the west bank of the Volga River could not cross the river because the river did not freeze in the winter of 1771 and Catherine the Great executed influential nobles among them.[19] After seven months of travel, only one third (66,073)[19] of the original group reached Dzungaria (Balkhash Lake, western border of the Manchu Qing Empire).[23] The Qing Empire resettled the Kalmyks in five different areas to prevent their revolt and several influential leaders of the Kalmyks died soon afterwards (killed by the Manchus). Following the Russian revolution their settlement was accelerated, Buddhism stamped out and herds collectivised.

Kalmykian nationalists and Pan-Mongolists attempted to migrate from Kalmykia to Mongolia in the 1920s when a serious famine gripped Kalmykia. On January 22, 1922, Mongolia proposed to accept the immigration of the Kalmyks but the Russian government refused. Some 71–72,000 (around half of the population) Kalmyks died during the famine.[24] The Kalmyks revolted against Russia in 1926, 1930 and 1942–1943. In March 1927, Soviet deported 20,000 Kalmyks to Siberia, and Karelia.[24] The Kalmyks founded the sovereign Republic of Oirat-Kalmyk on March 22, 1930. The Oirat state had a small army and 200 Kalmyk soldiers defeated a force of 1,700 Soviet soldiers in Durvud province of Kalmykia but the Oirat state was destroyed by the Soviet Army in 1930. The Mongolian government suggested to accept the Mongols of Soviet Union, including Kalmyks, to Mongolia but Russia refused the attempt. [24]

In 1943, the entire population of 120,000 Kalmyks were deported to Siberia by Stalin, accused of supporting invading Axis armies attacking Stalingrad (Volgograd); a fifth of the population is thought to have perished during and immediately after the deportation. [25][26][27] Around half (97–98,000) of the Kalmyk people deported to Siberia died before being allowed to return home in 1957.[28] The government of the Soviet Union forbade teaching the Kalmyk language during the deportation.[29][30][31] Mongolian leader Khorloogiin Choibalsan attempted to arrange migration of the deportees to Mongolia and he met them in Siberia during his visit to Russia. Under the Law of the Russian Federation of April 26, 1991 "On Rehabilitation of Exiled Peoples" repressions against Kalmyks and other peoples were qualified as an act of genocide. Today they are trying to revive their language and religion. In 2010 there were 176,800 Kalmyks.

Xinjiang Mongols

The Mongols of Xinjiang form a minority, principally in the northern part of the region, numbering 194,500 in 2010, about 50,000 of which are Dongxiangs.[32] They are primarily descendants of the surviving Torghuts and Khoshuts who returned from Kalmykia, and of the Chakhar stationed there as garrison soldiers in the 18th century. The emperor had sent messages asking the Kalmyks to return, and erected a smaller copy of the Potala in Jehol (Chengde), (the country residence of the Manchu Emperors) to mark their arrival. A model copy of that "Little Potala" was made in China for the Swedish explorer Sven Hedin, and was erected at the World's Columbian Exposition of Chicago (1893). It is now in storage in Sweden, where there are plans to re-erect it. Some of the returnees did not come that far and still live, now as Muslims, at the southwestern end of Lake Issyk-kul in present-day Kyrgyzstan.

In addition to sending Han exiles convicted of crimes to Xinjiang to be slaves of Banner garrisons there, the Qing also practiced reverse exile, exiling Inner Asian (Mongol, Russian and Muslim criminals from Mongolia and Inner Asia) to China proper where they would serve as slaves in Han Banner garrisons in Guangzhou. Russian, Oirats and Muslims (Oros. Ulet. Hoise jergi weilengge niyalma) such as Yakov and Dmitri were exiled to the Han banner garrison in Guangzhou.[33] In the 1780s after the Muslim rebellion in Gansu started by Zhang Wenqing (張文慶) was defeated, Muslims like Ma Jinlu (馬進祿) were exiled to the Han Banner garrison in Guangzhou to become slaves to Han Banner officers.[34] The Qing code regulating Mongols in Mongolia sentenced Mongol criminals to exile and to become slaves to Han bannermen in Han Banner garrisons in China proper.[35]

Alasha Mongols

Bordering Gansu and west of Irgay River is called Alxa or Alaša, Alshaa and Mongols who moved there are called the Alasha Mongols.

Törbaih Güshi Khan's 4th son Ayush was opposed to the Khan's brother Baibagas. Ayush's eldest son is Batur Erkh Jonon Khoroli. After the battle between Galdan Boshigt Khan and Ochirtu Sechen Khan, Batur Erkh Jonon Khoroli moved to Tsaidam with his 10,000 households. The 5th Dalai Lama wanted land for them from the Qing government, thus in 1686, the Emperor permitted them to reside in Alasha.

In 1697, Alasha Mongols were administered in 'khoshuu' and 'sum' units. A khoshuu with eight sums was created, Batur Erkh Jonon Khoroli was appointed to Beil (prince), and Alasha was thus a 'zasag-khoshuu'. Alasha was however like an 'aimag' and never administered under a 'chuulgan'.

In 1707, when Batur Erkh Jonon Khoroli died, his son Abuu succeeded him. He was in Beijing from his youth, served as bodyguard of the Emperor, and a princess (of the Emperor) was given to him, thus making him a 'Khoshoi Tavnan', i.e. Emperor's groom. In 1793, Abuu became Jün Wang. There are several thousand Muslim Alasha Mongols.[36]

Ejine Mongols

Mongols who lived along the Ejin River (Ruo Shui) descended from Ravjir, a grandson of Torghut Ayuka Khan from the Volga River.

In 1678, Ravjir, with his mother, younger sister and 500 people, went to Tibet to pray. While they were returning via Beijing in 1704, the Qing ruler, the Kangxi Emperor, let them stay there for some years and later organized a 'khoshuu' for them in a place called Sertei, and made Ravjir the governor.

In 1716, the Kangxi Emperor sent him with his people to Hami, near the border of Qing China and Zunghar Khanate, for intelligence-gathering purposes against the Oirats. When Ravjir died his eldest son Denzen succeeded him. He was afraid of the Zunghar and wanted the Qing government to allow them to move away from the border. They were settled in Dalan Uul–Altan. When Denzen died in 1740, his son Lubsan Darjaa succeeded him and became Beil. Now Ejine Torghuts number some 5000.

In 1753, they were settled on the banks of the Ejin River and the Ejin River Torghut 'khoshuu' was thus formed.[37]

Origins and genetics

Haplogroup C2*-Star Cluster which was thought to be carried by likely male-line descendants of Genghis Khan and Niruns (original Mongols and Descendants of Alan Gua) represented only 1.6% in Oirats.[38]

Y-chromosome in 426 individuals mainly from three major tribes of the Kalmyks (the Torghut, Dörbet and Khoshut)[39]:

C-M48:38.7

C-M407:10.8

N1c:10.1

R2:7.7

O2:6.8

C2(not M407, not M48) :6.6

O1b:5.2

R1:4.9

Others:9.2

Haplogroup C2*-Star Cluster represented only 2%( 3% of Dörbet and 2.7% of the Torghut).

Tribes

Sart Kalmyks and Xinjiang Oirats are not Volga Kalmyks or Kalmyks, and the Kalmyks are a subgroup of the Oirats.

See also

- Demographics of Mongolia

- Four Oirats

- Kalmyk people

- Dzungar

- Kalmykia

- Altay people

- Al-Adil Kitbugha (Oirat Sultan of Egypt)

References

- Owen Lattimore, The Desert Road to Turkestan. (For Lattimore, Euleuths are "the great western group of tribes which marks in all probability a primitive racial cleavage" (p. 101 in the ca. 1929 edition). Lattimore further (p. 139 refers to Samuel Couling of The Encyclopaedia Sinica (1917), according to whom the spelling "Eleuth" was due to French missionaries, representing the sound of something like Ölöt. Into Chinese, the same name was transcribed as 厄鲁特 (Pinyin: Elute; Mongolian: Olot).))

- M.Sanjdorj, History of the Mongolian People's Republic, Volume I, 1966

- 厄鲁特蒙古历史变迁中的一些问题(作者:郭蕴华). zh:新疆社会科学. 1984-03-01. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- N. Yakhontova, The Mongolian and Oirat Translations of the Sutra of Golden Light, 2006 Archived May 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast: from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. p. 169. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.

- Bassin, Mark; Kelly, Catriona (2012). Soviet and Post-Soviet Identities. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-107-01117-5.

- Crossley 2006, p. 64.

- History of Mongolia, Volume II, 2003

- Reuven Amitai Press, The Mongols and the Mamluks, p.94

- James Waterson, John Man. The Knights of Islam, p.205

- eds. Wezler, Hammerschmidt 1992, p. 194.

- Anglo-Mongolian Society 1983, p. 1.

- A Regional Handbook on Northwest China, Volume 1 1956, p. 53.

- "Islamic Culture". Deccan. 1 January 1971. Retrieved 4 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- БУЦАЖ ИРЭЭГҮЙ МОНГОЛ АЙМГУУД Archived 2013-11-15 at the Wayback Machine (Mongolian)

- Michael Edmund Clarke, In the Eye of Power (doctoral thesis), Brisbane 2004, p37 Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- René Grousset The Empire of the Steppes, p.521

- Government of the Republic of Kalmykia: Kalm.ru Archived June 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ТИВ ДАМНАСАН НҮҮДЭЛ (Mongolian)

- Perdue, Peter C. (30 June 2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674042025. Retrieved 4 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- Maksimov, Konstantin Nikolaevich (1 January 2008). Kalmykia in Russia's Past and Present National Policies and Administrative System. Central European University Press. ISBN 9789639776173. Retrieved 4 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- К вопросу о бегстве волжских калмыков в Джунгарию в 1771 году Archived 2012-07-25 at the Wayback Machine (Russian)

- Michael Khodarkovsky (2002). Russia's Steppe Frontier: The Making Of A Colonial Empire, 1500–1800. Indiana University Press. p.142. ISBN 0253217709

- XX зууны 20, 30-аад онд халимагуудын 98 хувь аймшигт өлсгөлөнд автсан (Mongolian)

- Minorityrights.org Archived 2014-01-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "rohan.sdsu.edu". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-21. Retrieved 2017-09-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Regions and territories: Kalmykia". BBC News. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- "Kalmyk: An ostracized language in Russia - Language webzine by Freelang". Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ling.hawaii.edu Archived 2015-06-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Deportation of the Kalmyks (1943–1956): Stigmatized Ethnicity

- James A. Millward Eurasian crossroads: a history of Xinjiang, p. 89

- Yongwei, MWLFZZ, FHA 03-0188-2740-032, QL 43.3.30 (April 26, 1778).

- Šande 善德, MWLFZZ, FHA 03-0193-3238-046, QL 54.5.6 (May 30, 1789) and Šande, MWLFZZ, FHA 03-0193-3248-028, QL 54.6.30 (August 20, 1789).

- 1789 Mongol Code (Ch. 蒙履 Menggu lüli, Mo. Mongγol čaγaǰin-u bičig), (Ch. 南省,給駐防爲, Mo. emün-e-tü muji-dur čölegüljü sergeyilen sakiγči quyaγ-ud-tur boγul bolγ-a). Mongol Code 蒙例 (Beijing: Lifan yuan, 1789; reprinted Taibei: Chengwen chubanshe, 1968), p. 124. Batsukhin Bayarsaikhan, Mongol Code (Mongγol čaγaǰin – u bičig), Monumenta Mongolia IV (Ulaanbaatar: Centre for Mongol Studies, National University of Mongolia, 2004), p. 142.

- James Stuart Olson An ethnohistorical dictionary of China, p. 242

- Xiaoyuan Liu Reins of liberation, p. 36

- V. Derenko, M; Malyarchuk, Boris; Woźniak, Marcin; Denisova, Galina; Dambueva, Irina; M. Dorzhu, C; Grzybowski, Tomasz; Zakharov-Gezekhus, Ilya (2007-03-01). "Distribution of the male lineages of Genghis Khan's descendants in northern Eurasian populations". Russian Journal of Genetics. 43 (3): 334–337. doi:10.1134/S1022795407030179.

- "Y-chromosome diversity in the Kalmyks at the ethnical and tribal levels".

Further reading

- Kempf, Béla: 'Ethnonyms and etymology - The case of Oyrat and beyond'. In: Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher. 24: 2010-11, pp. 189-203

- Khoyt S.K. Last data by localisation and number of oyirad (oirat) (htm republication) - in Russian

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wang Jinglan, Shao Xingzhou, Cui Jing et al. Anthropological survey on the Mongolian Tuerhute tribe in He shuo county, Xinjiang Uigur autonomous region // Acta anthropologica sinica. Vol. XII, № 2. May 1993. p. 137-146.

- Санчиров В. П. О Происхождении этнонима торгут и народа, носившего это название // Монголо-бурятские этнонимы: cб. ст. — Улан-Удэ: БНЦ СО РАН, 1996. C. 31—50. - in Russian

- Ovtchinnikova O., Druzina E., Galushkin S., Spitsyn V., Ovtchinnikov I. An Azian-specific 9-bp deletion in region V of mitochondrial DNA is found in Europe // Medizinische Genetic. 9 Tahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Humangenetik, 1997, p. 85.

- Galushkin S.K., Spitsyn V.A., Crawford M.H. Genetic Structure of Mongolic-speaking Kalmyks // Human Biology, December 2001, v.73, no. 6, pp. 823–834.

- Хойт С.К. Генетическая структура европейских ойратских групп по локусам ABO, RH, HP, TF, GC, ACP1, PGM1, ESD, GLO1, SOD-A // Проблемы этнической истории и культуры тюрко-монгольских народов. Сборник научных трудов. Вып. I. Элиста: КИГИ РАН, 2009. с. 146-183. - in Russian

- hamagmongol.narod.ru/library/khoyt_2008_r.htm Хойт С.К. Антропологические характеристики калмыков по данным исследователей XVIII-XIX вв. // Вестник Прикаспия: археология, история, этнография. № 1. Элиста: Изд-во КГУ, 2008. с. 220-243.

- Хойт С.К. Кереиты в этногенезе народов Евразии: историография проблемы. Элиста: Изд-во КГУ, 2008. – 82 с. ISBN 978-5-91458-044-2 (Khoyt S.K. Kereits in enthnogenesis of peoples of Eurasia: historiography of the problem. Elista: Kalmyk State University Press, 2008. – 82 p. (in Russian))

- hamagmongol.narod.ru/library/khoyt_2012_r.htm Хойт С.К. Калмыки в работах антропологов первой половины XX вв. // Вестник Прикаспия: археология, история, этнография. № 3, 2012. с. 215-245.

- Boris Malyarchuk, Miroslava Derenko, Galina Denisova, Sanj Khoyt, Marcin Wozniak, Tomasz Grzybowski and Ilya Zakharov Y-chromosome diversity in the Kalmyks at the ethnical and tribal levels // Journal of Human Genetics (2013), 1–8.

- Хойт С.К. Этническая история ойратских групп. Элиста, 2015. 199 с. (Khoyt S.K. Ethnic history of oyirad groups. Elista, 2015. 199 p. in russian)

- Joo-Yup Lee Were the historical Oirats “Western Mongols”? An examination of their uniqueness in relation to the Mongols // Études mongoles & sibériennes, centrasiatiques & tibétaines (47/2016)

- Хойт С.К. Данные фольклора для изучения путей этногенеза ойратских групп // Международная научная конференция «Сетевое востоковедение: образование, наука, культура», 7-10 декабря 2017 г.: материалы. Элиста: Изд-во Калм. ун-та, 2017. с. 286-289. (in russian)

- Ли Чжиюань. О происхождении хойдского народа // Международная научная конференция «Сетевое востоковедение: образование, наука, культура», 7-10 декабря 2017 г.: материалы. Элиста: Изд-во Калм. ун-та, 2017. с. 436-445. (in mongol)

External links

- Center for Oirad Studies, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

- Oirad community portal, in Mongolian language

- Oirad cultural events web portal, in Mongolian language