Offshore (novel)

Offshore is a 1979 novel by Penelope Fitzgerald. Her third novel, it won the Booker Prize in the same year. The book explores the emotional restlessness of houseboat dwellers who live neither fully on the water nor fully on the land. It was inspired by the most difficult years of Fitzgerald's own life, years during which she lived on an old Thames sailing barge moored at Battersea Reach.

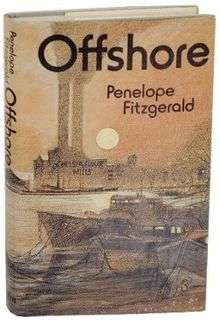

First edition | |

| Author | Penelope Fitzgerald |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | George Murray |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Publisher | Collins[1] |

Publication date | 1979 |

| Pages | 141[1] |

| ISBN | 0-395-47804-9 |

| OCLC | 38043106 |

Plot summary

The novel, set in 1961, follows an eccentric community of houseboat owners whose permanently moored craft cluster together along the unsalubrious bank of the River Thames at Battersea Reach, London. Nenna, living aboard Grace with her two children Martha and Tilda, is obsessed with thoughts of her estranged husband Edward returning to her, while her children run wild on the muddy foreshore. Maurice, who lives next to her on a barge he has named Maurice, provides a sympathetic ear for her worries. He ekes out a precarious living as a male prostitute, bringing back men most evenings from the nearby pub, and allowing his boat to be used for the storage of stolen goods by his shadowy acquaintance, Harry. Willis, an elderly marine painter, lives aboard Dreadnought which he hopes to sell in spite of its serious leak. Woodie is a retired businessman living aboard Rochester during the summer and with his wife Janet in Purley during the winter. Richard, aboard his converted minesweeper Lord Jim, is looked up to as the unofficial leader of the community, both by temperament and by virtue of his past role with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. His wife Laura hankers to move to a permanent house ashore.

When Dreadnought unexpectedly sinks, Willis is taken in by Woodie on Rochester. Nenna resists the entreaties of her prosperous and energetic sister, who tries to persuade her to move to Canada for the sake of her daughters, and she resolves to confront Edward in his rented room in Stoke Newington, north London. Failing to persuade him to return, she gets back to Grace late at night feeling desolate, and bumps into Richard who tells her that his wife has just left him. They spend the night together.

Richard discovers Harry acting suspiciously on Maurice. Harry attacks him, and Richard ends up in hospital. Laura takes her husband's incapacity as the excuse she needs to sell Lord Jim and to move herself and Richard into a proper house.

Maurice sits out an overnight storm in his cabin, drinking whisky in the dark. He hears blundering footsteps overhead and discovers that Edward (whom he does not know) has returned, incapably drunk, trying to find Nenna. The storm has blown away the gangplank between Maurice and Grace and, almost delirious with drink, the two men climb down Maurice's fixed ladder, intending somehow to cross the wild water between the two boats. As they cling to the ladder, Maurice's anchor is wrenched from the mud, its mooring ropes part, and the boat puts out on the tide.

Principal characters

- Nenna James, Canadian, with two children (Martha, 12 and Tilda, 6) living aboard Grace

- Edward, her estranged husband, now living in north London

- Richard Blake and his wife Laura, living aboard Lord Jim

- Sam Willis, an elderly marine painter, living aboard Dreadnought

- Maurice, a male prostitute, living aboard Maurice

- Woodie, a retired businessman living during the summer aboard Rochester.

Epigraph

The novel's epigraph, "che mena il vento, e che batte la pioggia, e che s'incontran con si aspre lingue" ("whom the wind drives, or whom the rain beats, or those who clash with such bitter tongues") comes from Canto XI of Dante's Inferno.

Background

The book was inspired by the most difficult years of Fitzgerald's own life, years that she had spent living on an old Thames sailing barge named Grace on Battersea Reach. She later regretted that some translations of the novel's title suggested "far from the shore" when she was in fact writing about boats that were anchored just a few yards from the bank, and the "emotional restlessness of my characters, halfway between the need for security and the doubtful attraction of danger".[2]

Critical reception

The novel was reviewed in The New York Times Book Review,[3]The Independent[4] and The Guardian.[5]

In his Understanding Penelope Fitzgerald (2004), Peter Wolfe characterised the novel as "a pocket epic, packing into 141 pages the piecemeal dissolution of a way of life".[6] He considered the work to be that of a master[7] – more darkly expansive than Fitzgerald's first two novels while displaying the same tightness and precision.[6] The author employs, he said, a sensual descriptive style with closely interlocked narrative, and her uncanny gift for describing the commonplace and overlooked galvanises the flow.[8]

In a 2013 introduction, Alan Hollinghurst noted that Offshore was the novel in which Fitzgerald found her form – her technique and her power. He noted that the group portrait of the boat owners within the novel is constantly developing, change and flux being the essence of the book, with the author moving between the strands of the story with insouciant wit and ease.[2]

Booker Prize

Offshore won the Booker Prize in 1979.[9] Hilary Spurling, one of the judges, later said that the panel was unable to decide between A Bend in the River and Darkness Visible, settling on Offshore as a compromise.[10] The book's surprise win was greeted with a reaction that Fitzgerald's publisher described as "so unpleasant a demonstration of naked spite".[11]

References

- "British Library Item details". primocat.bl.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Hollinghurst, Alan (2013). Offshore. London: Fourth Estate. Introduction viii - ix. ISBN 978-0-00-732096-7.

- Williamson, Barbara Fisher. "Quiet Lives Afloat". New York Times on the Web. The New York Times. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Sturges, Fiona. "Book Review: Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald". The Independent. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Day, Elizabeth. "Offshore by Penelope Fitzgerald". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Wolfe 2004, p. 112.

- Wolfe 2004, p. 136.

- Wolfe 2004, p. 134.

- "Offshore". The Man Booker Prize. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- Hilary Spurling (3 August 2008). "Modesty was her metier". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Jonathan Derbyshire (4 November 2016). "The politics of literary prize-giving". Financial Times. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

Bibliography

- Wolfe, Peter (2004). Understanding Penelope Fitzgerald. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-561-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)@