Possession (Byatt novel)

Possession: A Romance is a 1990 best-selling novel by British writer A. S. Byatt that won the 1990 Booker Prize. The novel explores the postmodern concerns of similar novels, which are often categorised as historiographic metafiction, a genre that blends approaches from both historical fiction and metafiction.

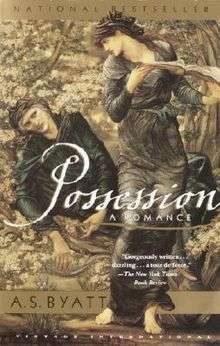

First American edition cover | |

| Author | A. S. Byatt |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Chatto & Windus |

Publication date | 1990 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 511 pp |

| ISBN | 978-0-7011-3260-6 |

The novel follows two modern-day academics as they research the paper trail around the previously unknown love life between famous fictional poets Randolph Henry Ash and Christabel LaMotte. Possession is set both in the present day and the Victorian era, contrasting the two time periods, as well as echoing similarities and satirising modern academia and mating rituals. The structure of the novel incorporates many different styles, including fictional diary entries, letters and poetry, and uses these styles and other devices to explore the postmodern concerns of the authority of textual narratives. The title Possession highlights many of the major themes in the novel: questions of ownership and independence between lovers; the practice of collecting historically significant cultural artefacts; and the possession that biographers feel toward their subjects.

The novel was adapted as a feature film by the same name in 2002, and a serialised radio play that ran from 2011 to 2012 on BBC Radio 4. In 2005 Time Magazine included the novel in its list of 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[1] In 2003 the novel was listed on the BBC's survey The Big Read.[2]

Background

The novel concerns the relationship between two fictional Victorian poets, Randolph Henry Ash (whose life and work are loosely based on those of the English poet Robert Browning, or Alfred, Lord Tennyson, whose work is more consonant with the themes expressed by Ash, as well as Tennyson's having been poet-laureate to Queen Victoria) and Christabel LaMotte (based on Christina Rossetti),[3] as uncovered by present-day academics Roland Michell and Maud Bailey. Following a trail of clues from letters and journals, they collaborate to uncover the truth about Ash and LaMotte's relationship, before it is discovered by rival colleagues. Byatt provides extensive letters, poetry and diaries by major characters in addition to the narrative, including poetry attributed to the fictional Ash and LaMotte.

A. S. Byatt, in part, wrote Possession in response to John Fowles' novel The French Lieutenant's Woman (1969). In an essay in Byatt's nonfiction book, On Histories and Stories, she wrote:

Fowles has said that the nineteenth-century narrator was assuming the omniscience of a god. I think rather the opposite is the case—this kind of fictive narrator can creep closer to the feelings and inner life of characters—as well as providing a Greek chorus—than any first-person mimicry. In 'Possession' I used this kind of narrator deliberately three times in the historical narrative—always to tell what the historians and biographers of my fiction never discovered, always to heighten the reader's imaginative entry into the world of the text.[4]

Plot summary

Obscure scholar Roland Michell, researching in the London Library, discovers handwritten drafts of a letter by the eminent Victorian poet Randolph Henry Ash, which lead him to suspect that the married Ash had a hitherto unknown romance. He secretly takes away the documents – a highly unprofessional act for a scholar – and begins to investigate. The trail leads him to Christabel LaMotte, a minor poet and contemporary of Ash, and to Dr. Maud Bailey, an established modern LaMotte scholar and distant relative of LaMotte. Protective of LaMotte, Bailey is drawn into helping Michell with the unfolding mystery. The two scholars find more letters and evidence of a love affair between the poets (with evidence of a holiday together during which – they suspect – the relationship may have been consummated); they become obsessed with discovering the truth. At the same time, their own personal romantic lives – neither of which is satisfactory – develop, and they become entwined in an echo of Ash and LaMotte. The stories of the two couples are told in parallel, and include letters and poetry by the poets.

The revelation of an affair between Ash and LaMotte would make headlines and reputations in academia because of the prominence of the poets, and colleagues of Roland and Maud become competitors in the race to discover the truth, for all manner of motives. Ash's marriage is revealed to have been unconsummated, although he loved and remained devoted to his wife. He and LaMotte had a short, passionate affair; it led to the suicide of LaMotte's companion (and possibly lover), Blanche Glover, and the secret birth of LaMotte's illegitimate daughter during a year spent in Brittany. LaMotte left the girl with her sister to be raised and passed off as her own. Ash was never informed that he and LaMotte had a child.

As the Great Storm of 1987 strikes England, the interested modern characters come together at Ash's grave, where they intend to exhume documents buried with Ash by his wife, which they believe hold the final key to the mystery. They also uncover a lock of hair. Reading the documents, Maud Bailey learns that rather than being related to LaMotte's sister, as she has always believed, she is directly descended from LaMotte and Ash's illegitimate daughter. Maud is thus heir to the correspondence by the poets. Now that the original letters are in her possession, Roland Michell escapes the potential dire consequences of having stolen the original drafts from the library. He sees an academic career open up before him. Bailey, who has spent her adult life emotionally untouchable, sees possible future happiness with Michell.

In an epilogue, Ash has an encounter with his daughter Maia in the countryside. Maia talks with Ash for a brief time. Ash makes her a crown of flowers, and asks for a lock of her hair. This lock of hair is the one buried with Ash which was discovered by the scholars, who believed it to be LaMotte’s. Thus it is revealed that both the modern and historical characters (and hence the reader), have, for the latter half of the book, misunderstood the significance of one of Ash's key mementoes. Ash asks the girl to give LaMotte a message that he has moved on from their relationship and is happy. After he walks away, Maia returns home, breaks the crown of flowers while playing, and forgets to pass the message on to LaMotte.

Reception

American writer Jay Parini in the New York Times, wrote "a plenitude of surprises awaits the reader of this gorgeously written novel. A. S. Byatt is a writer in mid-career whose time has certainly come, because Possession is a tour de force that opens every narrative device of English fiction to inspection without, for a moment, ceasing to delight." Also "The most dazzling aspect of Possession is Ms. Byatt's canny invention of letters, poems and diaries from the 19th century".[3]

Critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, writing in the New York Times, noted that what he describes as the "wonderfully extravagant novel" is "pointedly subtitled 'A Romance'."[5] He says it is at once "a detective story" and "an adultery novel."[5]

Writing in the Guardian online, Sam Jordison, who described himself as "a longstanding Byatt sceptic", wrote that he was: "caught off-guard by Possession's warmth and wit" ... "Anyone and everything that falls under Byatt's gaze is a source of fun." Commenting on the invented 'historical' texts he said their "effect is dazzling – and similarly ludic erudition is on display throughout." ... "Yet more impressive are in excess of 1,700 lines of original poetry". "In short, the whole book is a gigantic tease – which is certainly satisfying on an intellectual level" but, "Possession's true centre is a big, red, beating heart. It's the warmth and spirit that Byatt has breathed into her characters rather than their cerebral pursuits that makes us care". Concluding, "There's real magic behind all the brainy trickery and an emotional journey on top of the academic quest. So I loved it."[6]

Awards and nominations

- 1990 Booker Prize

- 1990 Irish Times-Aer Lingus International Fiction Prize[7]

Adaptations

The novel was adapted as a 2002 feature film by the same name, starring Gwyneth Paltrow as Maud Bailey; Aaron Eckhart as Roland Michell; and Jeremy Northam and Jennifer Ehle as the fictional poets Randolph Henry Ash and Christabel LaMotte, respectively. The film differs considerably from the novel.[8]

The novel was also adapted as a radio play, serialised in 15 parts between 19 December 2011 and 6 January 2012, on BBC Radio 4's Woman's Hour. it featured Jemma Redgrave as Maud, Harry Hadden-Paton as Roland, James D'Arcy as Ash and Rachael Stirling as LaMotte.[9]

References

- "All-Time 100 Novels". Time. 16 October 2005.

- "BBC – The Big Read". BBC. April 2003. Retrieved 31 October 2012

- Parini, Jay. "Unearthing the Secret Lover". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- A.S. Byatt On Histories and Stories (2001), p. 56. qtd in Lisa Fletcher "Historical Romance, Gender and Heterosexuality: John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman and A.S. Byatt’s Possession", Journal of Interdisciplinary Gender Studies vol.7 2003, p30.

- Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, Books of The Times; "When There Was Such a Thing as Romantic Love", The New York Times, 25 October 1990. Retrieved 23 January 2014

- "Guardian book club: Possession by AS Byatt". The Guardian 19 June 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "2 Novelists Awarded Fiction Prizes in Ireland", The New York Times, 6 October 1990

- Zalewski, Daniel (18 August 2002). "FILM; Can Bookish Be Sexy? Yeah, Says Neil LaBute". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Woman's Hour Drama – Possession (Programme Information)". BBC Media Centre. BBC. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

Further reading

- Bentley, Nick. "A.S. Byatt, Possession: A Romance". In Contemporary British Fiction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), 140–48. ISBN 978-0-7486-2420-1.

- Wells, Lynn K. (Fall 2002). "Corso, Ricorso: Historical Repetition and Cultural Reflection in A. S. Byatt's Possession: A Romance". MFS Modern Fiction Studies. 48 (3): 668–692. doi:10.1353/mfs.2002.0071.