Odontopteryx

Odontopteryx is a genus of the prehistoric pseudotooth birds or pelagornithids. These were probably rather close relatives of either pelicans and storks, or of waterfowl, and are here placed in the order Odontopterygiformes to account for this uncertainty.[2]

| Odontopteryx | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

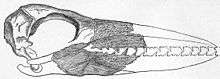

| Skull and hind part of jaws | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | †Pelagornithidae (but see text) |

| Genus: | †Odontopteryx Owen, 1873 |

| Species | |

|

O. toliapica Owen, 1873 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

[1] Species-level: | |

Species and taxonomy

One species of Odontopteryx has been formally described, but several other named taxa of pseudotooth birds might belong here too. The type species Odontopteryx toliapica is known from the Ypresian (Early Eocene) London Clay of the Isle of Sheppey (England) and slightly older rocks of the Ouled Abdoun Basin (Morocco). Its tarsometatarsus (e.g. specimen BMNH A4962) was for some time in the late 20th century believed to be from a giant procellariiform and called Neptuniavis minor, but specimen BMNH A44096 – the holotype skull described by Richard Owen in 1873 – was the first pelagornithid recognized as such, and not assigned to some other seabird lineage. It was still often allied with Sulidae (boobies and gannets) or Diomedeidae (albatrosses), to which it is quite certainly not closely related.[3]

One to five (or perhaps more) additional unnamed species are tentatively assigned to the present genus, mainly due to their size and/or forward-angled "teeth": one smaller and one larger than O. toliapica and also from the Late Paleocene or Early Eocene of the Ouled Abdoun Basin in Morocco, one from the mid-Eocene of Uzbekistan, one from Middle Eocene strata of the Tepetate Formation from near El Cien (Baja California Sur, Mexico), and one from the Early Eocene of Virginia, USA. As regards the Moroccan fossils, however, the largest of the three Odontopteryx-like forms (initially called "Odontopteryx n. sp. 2") has provisionally been termed "Odontopteryx gigas" but may in fact be a Dasornis, while the smallest ("Odontopteryx n. sp. 1") has been considered a distinct genus (as "Odontoptila inexpectata") but that name is both a nomen nudum[4] and would in any case be a junior homonym of the geometer moth genus Odontoptila and thus unavailable for the bird. Though the Mexican specimen (MHN-UABCS Te5/6–517, a distal humerus piece) agrees with O. toliapica in size and shape, it is not entirely clear whether the American forms belong in this otherwise Eurasian genus. It must be remembered, however, that at that their time the Isthmus of Panama had not been formed yet.[5]

Pseudodontornis tschulensis from the Late Paleocene of Zhylga (Kazakhstan) is sometimes placed in Odontopteryx, as is Macrodontopteryx oweni which was also found in the London Clay. In the latter case however, this does not seem to be correct (see below). The species originally described as O. longirostris was made the type species of Pseudodontornis in 1930. Small pelagornithid specimens have also been reported from the Early Oligocene Kishima Group and the Late Oligocene Ashiya Group of Japan, but their placement in Odontopteryx is even more uncertain.[6]

"Neptuniavis" minor was described from remains assigned to O. toliapica by Richard Lydekker in 1891. However, the supposed procellariiform genus Neptunavis is actually a pseudotooth bird too, and hence the smaller "species" is here synonymized as proposed by Lydekker. The type species "N." miranda, on the other hand, is a junior synonym of the large Dasornis emuinus. In a peculiar twist, some material assigned to "N." minor eventually turned out to be remains of the paleognath Lithornis vulturinus; the very first described bone of Dasornis emuinus on the other hand – a humerus piece – was at first mistaken for to be a Lithornis tarsometatarsus.[7]

Description and systematics

O. toliapica is among the smallest pseudotooth birds known to date – but this still means that to would have rivalled, if not exceeded, most living albatrosses in wingspan and the brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) in bulk. In life, its head (including the beak) would have been 20–25 cm (8–10 in) long. Unlike in most other pseudotooth birds, its "teeth" are slanted forwards.[8]

Like those of its relatives, the thin-walled bones of Odontopteryx broke easily and thus very few fossils – though still far more than of the average pseudotooth bird genus – are decently preserved. In combination with its small (for pseudotooth birds) size, some traits allow to identify the present genus. It resembles Dasornis in having a jugal arch that is mid-sized, tapering and stout behind the orbital process of the prefrontal bone, unlike in the large Neogene Osteodontornis. Also, its paroccipital process is much elongated back- and downwards, again like in Dasornis but unlike in Pseudodontornis longirostris. Meanwhile, the distal humerus specimen from Mexico (MHN-UABCS Te5/6–517) which may or may not belongs in the present genus differs from the corresponding bone of Osteodontornis in a more narrow and less excavated surface between the external condyle and the ectepicondylar prominence, with the pit between these closer to the bone's end. Its quadrate bone, meanwhile, differed from that of Osteodontornis in a very broadly grooved dorsal head, a wide main shaft with a strongly curved lateral ridge and a small and somewhat forward-pointing orbital process. The forward center of the quadrate's ventral articulation ridge extends downwards and to the middle, and the pterygoid process is only slightly expanded to the upper center in Odontopteryx. The socket for the quadratojugal is displaced downwards. The quadrate of P. longirostris is not very well preserved; it agees with Odontopteryx in a broad main shaft but is closer to Osteodontornis in the straight main shaft ridge and its upward-directed ventral articulation ridge's forward center. Its quadratojugal socket differs from both.[9]

Odontopteryx differed from Pelagornis (a contemporary of Osteodontornis) and agreed with Dasornis[10] in having a deep and long handward-pointing pneumatic foramen in the fossa pneumotricipitalis of the humerus, a latissimus dorsi muscle attachment site on the humerus that consists of two distinct segments instead of a single long, and a large knob that extends along the ulna where the ligamentum collaterale ventrale attached. Further differences between Odontopteryx and Pelagornis are found in the tarsometatarsus: in the present genus, it lacks a deep fossa of the hallux' first metatarsal bone and its middle toe trochlea is conspicuously expanded forward. The salt glands inside the eye sockets were far less developed in Odontopteryx than in Pelagornis. As the traits shared between Odontopteryx and Dasornis are probably plesiomorphic however, they cannot be used to argue for a closer relationship between the two Paleogene genera than either had with Osteodontornis and/or Pelagornis.[2]

But even though – due to the lack of better-preserved fossils – a close relationship between Odontopteryx and Dasornis cannot be excluded for sure either, it seems that the Neogene pseudotooth birds all derive from a large Paleogene form – such as Dasornis or (if it is not actually identical with Pelagornis) the mysterious P. longirostris – and that the smallish lineage became entirely extinct before the Neogene (perhaps in the Grande Coupure). In 1891 O. toliapica was proposed as type genus of a family Odontopterygidae; recent authors generally place all pseudotooth birds in a single family. But if the evolutionary scenario outlined above is correct, the family name Pelagornithidae could be restricted to the giant lineage, and the Odontopterygidae reestablished as name for the smaller lineage. Macrodontopteryx was initially also included in the Odontopterygidae, but if not a distinct genus it is more likely a young individual of Dasornis. The only smallish Neogene pseudotooth bird known as of 2009 is "Pseudodontornis" stirtoni from New Zealand, which was about the size of O. toliapica. Its relationships are completely obscure.[11]

Footnotes

- Brodkorb (1963: p.262), Mayr (2008)

- Bourdon (2005), Mayr (2009: p.59)

- Woodward (1909: pp.86-87), Walsh & Hume (2001), Mlíkovský (2002: pp.81-82), paleocene-mammals.de (2008), Mayr (2008, 2009: pp.56,59)

- Like "O. gigas" it was only published in a thesis: ICZN (1999)

- González-Barba et al. (2002), Mlíkovský (2002: p.81), uBio (2005), Bourdon (2005, 2006), NEO (2008), paleocene-mammals.de (2008), Mayr (2008, 2009: pp.56-57)

- González-Barba et al. (2002), Mlíkovský (2002: pp.81-82), paleocene-mammals.de (2008), Mayr (2008, 2009: pp.56,58)

- Mlíkovský (2002: pp.58-59,78), Mayr (2008)

- Hopson (1964), González-Barba et al. (2002), Mayr (2008, 2009: pp.57,59)

- Ono (1989), González-Barba et al. (2002), Mayr (2008)

- = "Argillornis emuinus": Boudon (2005), Mayr (2008)

- Lanham (1947), Scarlett (1972), Brodkorb (1963: p.262), Olson (1985: p.195), González-Barba et al. (2002), Mlíkovský (2002: p.81), Mayr (2008, 2009: p.59)

References

- Bourdon, Estelle (2005): Osteological evidence for sister group relationship between pseudo-toothed birds (Aves: Odontopterygiformes) and waterfowls (Anseriformes). Naturwissenschaften 92(12): 586–591. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0047-0 (HTML abstract) Electronic supplement (requires subscription)

- Bourdon, Estelle (2006): L'avifaune du Paléogène des phosphates du Maroc et du Togo: diversité, systématique et apports à la connaissance de la diversification des oiseaux modernes (Neornithes) ["Paleogene avifauna of phosphates of Morocco and Togo: diversity, systematics and contributions to the knowledge of the diversification of the Neornithes"]. Doctoral thesis, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle [in French]. HTML abstract

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1963): Catalogue of fossil birds. Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences 7(4): 179–293. PDF or JPEG fulltext

- González-Barba, Gerardo; Schwennicke, Tobias; Goedert, James L. & Barnes, Lawrence G. (2002): Earliest Pacific Basin record of the Pelagornithidae (Aves, Pelecaniformes). J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 22(2): 722–725. DOI:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0722:EPBROT]2.0.CO;2 HTML abstract

- Hopson, James A. (1964): Pseudodontornis and other large marine birds from the Miocene of South Carolina. Postilla 83: 1–19. Fulltext at the Internet Archive

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) (1999): International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (4th ed.). International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, London. ISBN 0-85301-006-4 HTML fulltext

- Lanham, Urless N. (1947): Notes on the phylogeny of the Pelecaniformes. Auk 64(1): 65–70. DjVu fulltext PDF fulltext

- Mayr, Gerald (2008): A skull of the giant bony-toothed bird Dasornis (Aves: Pelagornithidae) from the Lower Eocene of the Isle of Sheppey. Palaeontology 51(5): 1107–1116. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00798.x (HTML abstract)

- Mayr, Gerald (2009): Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg & New York. ISBN 3-540-89627-9 Preview at Google Books

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe. Ninox Press, Prague. ISBN 80-901105-3-8 PDF fulltext

- NASA Earth Observatory (NEO) (2008): Panama: Isthmus that Changed the World. Version of 2008-SEP-22. Retrieved 2009-SEP-24.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1985): The Fossil Record of Birds. In: Farner, D.S.; King, J.R. & Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.): Avian Biology 8: 79-252. PDF fulltext

- Ono, Keiichi (1989): A Bony-Toothed Bird from the Middle Miocene, Chichibu Basin, Japan. Bulletin of the National Science Museum Series C: Geology & Paleontology 15(1): 33–38. PDF fulltext

- paleocene-mammals.de (2008): Genera and species of Paleocene birds. Version of 2008-FEB-10. Retrieved 2009-AUG-04.

- uBio (2005): Digital Nomenclator Zoologicus, version 0.86 3: 387. PDF fulltext

- Walsh, Stig A. & Hume, Julian P. (2001): A new Neogene marine avian assemblage from north-central Chile. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 21(3): 484–491. DOI:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0484:ANNMAA]2.0.CO;2 PDF fulltext

- Woodward, Arthur Smith (ed.) (1909): A Guide to the Fossil Mammals and Birds in the Department of Geology and Palaeontology of the British Museum (Natural History) (9th ed.). William Clowes and Sons Ltd., London. Fulltext at the Internet Archive

Further reading

- The Rise of Birds: 225 Million Years of Evolution by Sankar Chatterjee

- The Origin and Evolution of Birds by Alan Feduccia

- Fossils (Smithsonian Handbooks) by David Ward