Northampton railway station

Northampton railway station serves the large town of Northampton in England. It is on the Northampton Loop of the West Coast Main Line. The station is served by West Midlands Trains services southbound to London Euston and northbound to Birmingham New Street and Crewe. A handful of Avanti West Coast services also serve the station.

| Northampton | |

|---|---|

Station frontage | |

| Location | |

| Place | Northampton |

| Local authority | Borough of Northampton |

| Grid reference | SP747604 |

| Operations | |

| Station code | NMP |

| Managed by | London Northwestern Railway |

| Number of platforms | 5 |

| DfT category | C1 |

| Live arrivals/departures, station information and onward connections from National Rail Enquiries | |

| Annual rail passenger usage* | |

| 2014/15 | |

| 2015/16 | |

| 2016/17 | |

| 2017/18 | |

| 2018/19 | |

| History | |

| Original company | London and North Western Railway |

| Post-grouping | London, Midland and Scottish Railway London Midland Region of British Railways |

| 16 February 1859 | Opened as Northampton Castle |

| 1880–1881 | Rebuilt |

| 1965–66 | Remodelled |

| 27 September 1965 | Closure of motive power depot |

| 18 April 1966 | Renamed Northampton |

| 12 January 2015 | New station building opened |

| National Rail – UK railway stations | |

| |

Until 18 April 1966, the station was known as Northampton Castle, as it is built on the site of the former castle of that name. As part of the station's redevelopment in 2015, it was proposed to revert to this name. However, that did not happen.[1]

Facilities

The station has toilets, a newsagent, coffee shops, and a car hire office. As part of the re-development in 2015 there were proposals to build a multi-storey car park with direct access to the station.

Services

Northampton is served by West Midlands Trains services to London Euston and Birmingham New Street. WMT maintain their fleet of Class 350 EMUs at the Siemens depot just to the north of the station, as well as maintaining a Train Crew Depot at the station.

The typical Monday-Saturday off-peak service consists of:

- Southbound

- 3 trains per hour to London Euston.

- Northbound

- 1 train per hour to Rugeley Trent Valley via Birmingham New Street.

- 1 train per hour to Rugeley Trent Valley and Crewe (dividing at Birmingham New Street).

- 1 train per hour to Liverpool Lime Street via Birmingham New Street.

The service along the Trent Valley Line to Crewe via Nuneaton and Stafford no longer calls here (since December 2012); this service now runs on the direct (fast) lines between Milton Keynes Central and Rugby arising from the London Midland decision to run 110 mph regional services on the West Coast Main Line.[2] Passengers wishing to travel from Northampton to Crewe now have to change at Rugby. However, there are still six Crewe services on Mondays to Fridays (Three in the mornings, three in the evenings), three on Saturdays (In the morning only) and an hourly service on Sundays.[3]

Avanti West Coast operate two trains per day to London Euston (southbound only); one in the early morning and one in the late evening. These services originate from Rugby or Wolverhampton. However no northbound Avanti West Coast services are timetabled as serving Northampton. The lack of fast services at Northampton is caused by the town being bypassed by the fast lines of the West Coast Main Line (which follow the original route of the London and Birmingham Railway). Connections to Manchester and other long-distance destinations can be made by changing at Milton Keynes Central.

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rugby | London Northwestern Railway London – Crewe (off peak only) |

Terminus or Milton Keynes Central | ||

| Terminus | London Northwestern Railway London-Northampton |

Wolverton | ||

| Long Buckby |

London Northwestern Railway London/Northampton – Birmingham |

Terminus or Wolverton | ||

| Rugby |

Avanti West Coast Birmingham New Street to London Euston (off peak only) |

Milton Keynes Central or London Euston | ||

| Disused railways | ||||

| Pitsford and Brampton Line and station closed |

London and North Western Railway Northampton to Market Harborough line |

Northampton Bridge Street Line and station closed | ||

| Terminus | London, Midland and Scottish Railway Bedford to Northampton Line |

Piddington Line and station closed | ||

| Historical railways | ||||

| Church Brampton Line open, station closed |

London and North Western Railway Northampton Loop |

Roade Line open, station closed | ||

History

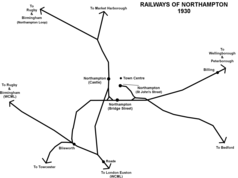

At one time there were three railway stations in Northampton: Northampton (Bridge Street), Northampton (St. John's Street) and Northampton (Castle), only the last of which now survives as the town's only station.

The railway reaches Northampton

Although the promoters of the London and Birmingham Railway had considered routes passing close to Northampton in 1830, the town was skirted by the final choice of alignment via Blisworth and a loop line to remedy this had to wait for several decades.[4] The decision to omit Northampton was not due to local opposition but rather engineering decisions taken by the railway company's engineer Robert Stephenson.[5][6] The 120 ft (37 m) difference in gradient in the 4 mi (6.4 km) between Northampton and Blisworth, on the floor of the Nene Valley, is likely to have played a key role in the decision.[7] Robert Stephenson is reported to have said that he could easily get trains into the town but not out again.[7] As a result, Northampton lost out as a commercial centre to towns such as Leicester which had better transport links.[7] The town was considered as the southern terminus of the Midland Counties Railway in 1833 but lost out to Rugby on account of the shorter distance with Leicester.[8]

Bridge Street station on the Northampton and Peterborough Railway from Blisworth to Peterborough East was thus the first station in Northampton, opening on 13 May 1845.[9]

1858 station

Following the discovery of a large quantity of ironstone in Northamptonshire in 1851, a proposal was made by the London and North Western Railway (L&NWR) for an 18 mi (29 km) line from Market Harborough to Northampton which received Parliamentary approval in 1853.[10] The line's terminus in Northampton was to be on part of the old orchard of Northampton Castle which had been purchased in 1852 by the Reverend Havilland de Sausmarez, the absentee Rector of the Parish of St Peter, as the site of a new rectory.[11] The L&NWR agreed to purchase the land for £5,250, to complete the parsonage and to rent it back to the Reverend.[11] Tenders were advertised for the line in 1858 and the lowest offer of £81,637 by Richard Dunkley of Blisworth was accepted.[12] The contractor had been an unsuccessful bidder for the contract to build Bridge Street station.[13] Dunkley was also the successful tenderer for the line's stations, including Castle station at a cost of £612.[14]

It would be the most basic structure on the line with no goods facilities, limited passenger waiting accommodation and an awning over the single platform.[15] Goods traffic was to be dealt with at Bridge Street.[16] The station opened with the line on 16 February 1859.[17][18][19][20][21] It was described in the L&NWR's minutes as a "very unassuming edifice", giving the impression that it was "merely temporary in nature" until traffic developed to a sufficient level to allow a "more imposing" structure to be built.[22]

1880–81 rebuilding

The advent of the Great Northern and London and North Western Joint Railway to tap the coalfields of Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire led the L&NWR to quadruple its main line between Bletchley and Rugby and also to consider ways in which Northampton might be better served.[23] In 1875, the L&NWR obtained powers to quadruple the main line north from Bletchley to Roade, with the two new tracks (the "slow lines") diverging at Roade so as to form a new line (the "Northampton Loop") through Northampton.[24] The result of these works would be to put Northampton on an important coal artery from Nottingham and the North to the L&NWR's Camden goods depot.[25]

Additional land would have to be purchased at Castle station to allow for expanded passenger facilities and goods facilities.[26] Owing to the proximity of the River Nene, the only way this could be done was to expand onto the site of Northampton Castle.[26] On 18 December 1876, the L&NWR purchased the site from William Walker and subsequently demolished the remains of the castle except for the postern gate which, following a local petition, was moved to a new site in the boundary wall of the new station where it remains to this day.[27][26] £30,000 was allowed by the L&NWR board for the improvement of passenger facilities[28] and a goods shed was constructed on the site of the castle in 1880.[24] The rebuilt station opened with the Loop Line north to Rugby on 1 December 1881 followed by the line south to Roade on 3 April 1882.[24][29] It comprised three through platforms and five terminal bays.[30] Platform 1, which was sited on the east side of the running lines, was considered as the main up platform; it had two adjoining bay platforms, numbered 2 and 3.[30] Platforms 4 and 5 were located at the south end of platform 1, while the two sides of an island platform on the down side of the station were platforms 6 and 7.[30] A further down bay platform was situated at the north end of platform 6, along with other bays and loading docks for parcels and sundries traffic.[30]

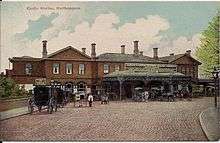

The main station building, a two-storey structure in the Italianate style, was located on the up side and consisted of a central block with two cross-wings.[30] The wings had gable roofs, whereas the central part had a low-pitched hipped roof.[30] Two standard L&NWR signal cabins were positioned to the north and south of the platforms, these being known respectively as Northampton No. 1 and No. 2 boxes.[30] Other signal cabins, Northampton No. 3 and No. 4, were sited further north and controlled extensive marshalling yards.[30] A fifth cabin at Duston West Junction lay to the south-west; it controlled the apex of the Northampton triangle.[30] No. 2 was the largest signal cabin with 118 levers which controlled the country end of the station, access to the goods shed and the south end of the goods yard.[31]

Modern times

Line closures

.jpg)

No further significant changes took place prior to nationalisation except for an increase in the number of sidings at the station.[32] One notable change was the traffic diverted from Northampton St John's following its closure in 1939.[33][34][35][36]

Closures accelerated under British Railways with the withdrawal of services from Bridge Street station, which lost much if not all of its significance following the opening of the Loop,[25] on 4 May 1964[9][35] when the Northampton to Peterborough line was closed, leaving only Castle station serving the town.[27] As a result, Castle station was renamed Northampton on 18 April 1966.[9][37] In addition, the bay platforms 4 and 5 were removed and the area converted into an overflow car park.[38] The Great Northern and London and North Western Joint Line closed to all passenger traffic except for a workmen's service on 7 December 1953; the workmen's service between Market Harborough and East Norton ended on 20 May 1957.[39] The section between Welham Junction and Marefield North Junction closed on November 1963, followed by the Rugby and Stamford Railway on 6 June 1966.[39] The line to Market Harborough closed on 15 August 1981.[40]

1965–66 remodelling

The station was chosen by British Rail for complete rebuilding in 1965–66 to designs by the architect Ray Moorcroft, as part of the electrification of the West Coast Main Line between Euston and Liverpool.[41][39][27] The Victorian station was demolished to be replaced by new structures which were described as "three cowsheds bolted together"[42] and as being of "questionable architectural merit".[30] The station layout remained unchanged: three long through platforms and a number of terminal bays.[43][30] Standard colour-light signalling was installed in the area but control was not centralised.[43] The current was switched on for the first time between Hillmorton Junction to Northampton on 6 June 1965 for insulation tests, with steam locomotives being withdrawn from the area on 27 September 1965.[41]

2013–14 rebuilding

By the late 2000s, the station had become inadequate for the size of the town which it served and the 2.5 million passengers who used it each year.[42] Following the designation of Northampton Waterside as an enterprise zone in August 2011,[44] plans to replace the existing station with a new two-storey glass and steel structure were approved by the West Northamptonshire Development Corporation.[45]

The redevelopment included a new 2,500 m2 (27,000 sq ft) station building nearly twice the size of the existing one, a new 1,270 space multi-storey car park, new footbridge and platform canopies, new approach roads and associated junction improvements, as well as a 28,000 m2 (300,000 sq ft) commercial development.[46][47] Funding for the new station was agreed in May 2012 when the coalition government agreed to provide £10m, with the remaining £10m coming from Network Rail and Northamptonshire County Council.[48] Construction work began in August 2013.[49] The new station opened on 12 January 2015.[50][51][51] This was followed by demolition of the old station and construction of a new station building. It is planned to build a new 1550 space multi-storey car park, with direct access to the booking hall, this is being developed by Northampton Borough Council and Network Rail as part of a wider proposal to develop the surrounding land for housing and commercial use.

Proposed renaming

Northamptonshire County Council wanted to rename the station "Northampton Castle" in recognition of the site's history.[52] The change, reported to cost £200,000,[52] looked unlikely to go ahead as of November 2015.

Media

The 2005 film Kinky Boots featured a station named 'Northampton', although the scenes were filmed at nearby Wellingborough on the Midland Main Line.

Accidents and incidents

Locomotive facilities

Motive power depots

For several years after 1849 engines were stabled in the open on a siding set aside for this purpose.[54] The first shed was a wooden structure opened in c. 1850 by the London and Birmingham Railway which was blown down in 1852.[55] A brick built replacement was provided in 1855 which was later enlarged in 1870 to receive extra locomotives from Wolverton shed which closed in 1874.[54] In 1881, a large 10-road replacement shed was constructed in the triangle of lines to the south of the station, with the 1855 shed subsequently used for carriage storage.[54][55] This shed, which was often referred to as Bridge Street, was located near the Grand Union Canal and could accommodate 50 engines.[54] Measuring 228 ft × 132 ft (69 m × 40 m) with a 42 ft (13 m) turntable, the shed was initially coded as No. 5 and became No. 6 on the opening of Bescot.[54] For administrative purposes, it was merged with Colwick shed upon the grouping and both remained under the control of the same shed foreman until Colwick's closure in 1932.[54] Northampton was coded 2C in 1935 when it was merged with Rugby shed; it remained 2C until December 1963 when it was recoded 1H by British Railways.[54]

Initially 16 locomotives were allocated to Northampton shed in the 1860s, a figure which had risen to 36 by 1925 despite receiving the allocation of the ex-Midland shed at Hardingstone Lane in 1924.[54] The stock level rose under British Railways when it comprised 8Fs, 4Fs and LNWR 0-8-0s for freight workings, 'Black Fives', 2-6-2Ts and 4-4-0s for passenger services, while a few 3Fs and a single Webb 2-4-2T were used for shunting.[54]

A re-arrangement of the offices and stores took place in 1927 under the London, Midland and Scottish Railway at a cost of nearly £1,000; the roof was also replaced by one with a 'louvre' pattern.[54] A new 60 ft (18 m) turntable was installed in 1938 by the south-east corner of the building.[54] Further modernisation took place in 1952 when ash and coaling plants were erected by British Railways, together with a new 70,000 imp gal (320,000 l) structure.[54] The shed was closed, along with Willesden shed, as from 27 September 1965, a consequence of the electrification of the West Coast Main Line.[54]

King's Heath depot

To the north of the station is a five-road Siemens rolling stock maintenance depot which officially opened on 27 June 2006; the depot is responsible for West Midland Train's entire Class 350 Desiro fleet which were introduced in June 2005.[56]

References

| Northampton loop | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- "Northampton rail station's £200K name plan attacked". BBC News Online. 9 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "London Midland Reveals Details of its "Project 110"". rail.co.uk. 8 March 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- GB National Rail Timetable December 2015 – May 2016, Tables 67 & 68

- Gough (1984), p. 8.

- Wake (1935), p. 17.

- Hatley (1959), pp. 305–309.

- Engel (2009), p. 61.

- Gough (1984), p. 9.

- Butt (1995), p. 172.

- Gough (1984), pp. 19, 23 and 28.

- Gough (1984), p. 30.

- Gough (1984), pp. 32–33.

- Gough (1984), p. 33.

- Gough (1984), pp. 41–42.

- Gough (1984), p. 42.

- Kingscott (2008), p. 69.

- Leleux (1984), p. 54.

- Harrison, Chaz (11 August 2009). "Ever wondered what lies beneath?". BBC News. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- William Page, ed. (1930). "The borough of Northampton: Introduction". A History of the County of Northampton. 3. pp. 1–26. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- Building Design Partnership (November 2006). "Northampton Central Area Design, development and movement framework (Final Report)" (PDF). para. 2.15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- Quick (2009), p. 295.

- Gough (1984), p. 52.

- Gough (1984), p. 61.

- Leleux (1984), p. 56.

- Gough (1984), p. 76.

- Gough (1984), p. 63.

- Kingscott (2008), p. 70.

- Gough (1984), p. 74.

- Gough (1984), p. 75.

- Jenkins (2016), p. 27.

- Adams (2012), p. 106.

- Gough (1984), p. 81.

- Butt (1995), p. 173.

- Kingscott (2008), p. 143.

- Mitchell & Smith (2007), fig. 62.

- Clinker (1988), p. 102.

- Mitchell & Smith (2007), fig. XVII.

- Adams (2012), pp. 98–99.

- Gough (1984), p. 85.

- Gough (1984), p. 87.

- Milner & Banks (2001), p. 66.

- Adams (2012), p. 92.

- Gough (1984), p. 86.

- HM Treasury (17 August 2011). "The Government announces 11 new Enterprise Zones to accelerate local growth, as part of the Plan for Growth". Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "Northampton's Castle station plans approved". BBC News Online. 12 August 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- West Northamptonshire Development Corporation (28 June 2012). "Redevelopment of Northampton rail station a step closer". Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- West Northamptonshire Development Corporation (15 October 2012). "Preparations for £20m Station to commence". Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "Northampton railway station redevelopment funding agreed". BBC News Online. 14 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "Work begins on Northampton's new £20m railway station". Northampton Chronicle & Echo. 19 August 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- "BREAKING NEWS: Northampton railway station to open no later than January 12 – Northampton Chronicle and Echo". Northampton Chronicle & Echo. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Milner, Chris (February 2015). "Northampton's £20 million station opens after delay". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 161 no. 1367. p. 83.

- "Northampton rail station's £200K name plan attacked". BBC News Online. 9 April 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- McCrickard, John P (6 October 2016). "January 1989 to December 1989". Network South East Railway Society. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Hawkins & Reeve (1981), p. 162.

- Griffiths (1999), p. 157.

- Mitchell & Smith (2007), fig. 70.

Sources

- Adams, Will (2012). Northamptonshire – Part 1: South and West. British Railways Past and Present. Kettering: Past & Present Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85895-284-0. No. 65.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Butt, R. V. J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations: details every public and private passenger station, halt, platform and stopping place, past and present (1st ed.). Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85260-508-7. OCLC 60251199.

- Clinker, C.R. (1988) [1978]. Clinker's Register of Closed Passenger Stations and Goods Depots in England, Scotland and Wales 1830–1980 (2nd ed.). Bristol: Avon-Anglia Publications & Services. ISBN 978-0-905466-91-0. OCLC 655703233.

- Engel, Matthew (2009). Eleven Minutes Late: A train journey into the soul of Britain. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-70898-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gough, John (1984). The Northampton & Harborough Line. Oakham: Railway and Canal Historical Society. ISBN 0-901461-35-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, Roger (1999). The directory of British engine sheds and principal locomotive servicing points: 1. Oxford: OPC. ISBN 0860935426.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hatley, Victor (1959). "Northampton Re-vindicated: More light on Why the Main Line Missed the Town". Northamptonshire Past and Present. II (6): 305–309. OL 22383432M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawkins, Chris; Reeve, George (1981). LMS Engine Sheds: The L&NWR. 1. Upper Bucklebury: Wild Swan. ISBN 0-906867-02-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkins, Stanley C. (April 2016). "Steam days at Northampton". Steam Days (320): 15–28.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kingscott, Geoffrey (2008). Lost Railways of Northamptonshire. Newbury, Berkshire: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-84674-108-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leleux, Robin (1984) [1976]. A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: The East Midlands. 9. Newton Abbot, Devon: David St. John Thomas. ISBN 978-0-946537-06-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milner, Chris; Banks, Chris (2001) [1991]. The East Midlands. British Railways Past and Present. Kettering: Past & Present Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85895-112-6. No. 10.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Victor E.; Smith, Keith A. (June 2007). Bletchley to Rugby (including Newport Pagnell and Northampton). Midhurst, West Sussex: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-1-906008-07-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quick, Michael (2009) [2001]. Railway passenger stations in Great Britain: a chronology (4th ed.). Oxford: Railway and Canal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-901461-57-5. OCLC 612226077.

- Wake, Joan (1935). Northampton Vindicated or Why the Main Line Missed the Town. Northampton: Joan Wake. ASIN B0018GPKOQ.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Healy, John M.C. (1989). The Last Days of Steam in Northamptonshire. Gloucester: Sutton. ISBN 0-86299-613-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Northampton railway station. |

- Train times and station information for Northampton railway station from National Rail

- Northampton Rail User's Group website

- History of Northampton