Nomocanon

A nomocanon (Greek: Νομοκανών, Nomokanōn; from the Greek nomos - law and kanon - a rule) is a collection of ecclesiastical law, consisting of the elements from both the Civil law and the Canon law. Nomocanons form part of the Oriental canon law of the Eastern Catholic Churches, and are also used by the Eastern Orthodox Churches.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

Jus antiquum (c. 33-1140)

Jus novum (c. 1140-1563) Jus novissimum (c. 1563-1918) Jus codicis (1918-present) Other |

|

Sacraments

Sacred places

Sacred times |

|

|

Supreme authority, particular churches, and canonical structures Supreme authority of the Church

Supra-diocesan/eparchal structures

|

|

|

Temporal goods (property) |

|

Canonical documents |

|

Procedural law Pars statica (tribunals & ministers/parties)

Pars dynamica (trial procedure)

Election of the Roman Pontiff |

|

Legal practice and scholarship

Academic degrees Journals and Professional Societies Faculties of canon law

Canonists |

|

|

Byzantine nomocanons

Collections of this kind were found only in Oriental canon law. The Greek Church has two principal nomocanonical collections.

The first nomocanon, in the sixth century, is ascribed, though without certainty, to John Scholasticus, whose canons it utilizes and completes. He had drawn up (about 550) a purely canonical compilation in 50 titles, and later composed an extract from the Justinian's Novellae in 87 chapters[1] that relate the ecclesiastical matters. To each of the 50 titles was added the texts of the imperial laws on the same subject, with 21 additional chapters, nearly all borrowed from John's 87 chapters.[2] Thus the Nomocanon of John Scholasticus was made.

The second nomocanon dates from the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610–641), at which time Latin was replaced by Greek as the official language of the imperial laws. It was made by fusion of Collectio tripartita (collection of Justinian's imperial law) and Canonic syntagma (ecclesiastical canons). Afterwards, this collection would be known as Nomocanon in 14 titles.

This nomocanon was long held in esteem and passed into the Russian Church, but it was by degrees supplanted by Nomocanon of Photios in 883.

The great systematic compiler of the Eastern Church, who occupies a similar position to that of Gratian in the West, was Photius, Patriarch of Constantinople in the 9th century. His collection in two parts—a chronologically ordered compilation of synodical canons and a revision of the Nomocanon—formed and still forms the classic source of ancient Church Law for the Greek Church.[3]

Basically it was Nomocanon in 14 titles with the addition of 102 canons of Trullan Council (see Canon law), 17 canons of the Council of Constantinople of 861,[4] and three canons substituted by Photios for those of the Council of Constantinople in 869. Nomocanon in 14 titles was completed with the more recent imperial laws.

This whole collection was commentated about 1170 by Theodore Balsamon,[5] Greek Patriarch of Antioch residing at Constantinople. Nomocanon of Photios was supplemented by this commentary and became Pedalion (Greek: Πηδάλιον - rudder), a sort of Corpus Juris of the Eastern Orthodox Church, printed in 1800 by Patriarch Neophytos VII.

Nomocanon of Photios retained in the law of the Greek Church and it was included in Syntagma, published by Rallis and Potlis (Athens, 1852–1859). Even though called Syntagma, the collection of ecclesiastical law of Matthew Blastares in 1335) is the real nomocanon, in which the texts of the laws and the canons are arranged in alphabetical order.[6]

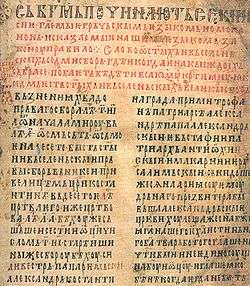

St. Sava's Nomocanon

The Nomocanon of Saint Sava or (Serbian: Zakonopravilo, Savino Zakonopravilo) was the first Serbian constitution and the highest code in the Serbian Orthodox Church, finished in 1219. This legal act was well developed. St. Sava's Nomocanon[7] was the compilation of Civil law, based on Roman Law[8][9] and Canon law, based on Ecumenical Councils and its basic purpose was to organize functioning of the young Serbian kingdom and the Serbian church.

During the Nemanjić dynasty (1166-1371) Serbian medieval state was flourishing in the spheres of politics, religion and culture. As the state developed, also the industry developed, so the law had to regulate various number of relations. Therefore, with the development of economy, Roman Law was taken. In that time Serbia was not a tsarish empire, so its ruler could not create code of laws, which would regulate the relations in the state and church. Serbian rulers reigned with single legal acts and decrees. In order to overcome this problem and organize legal system, after acquiring religious independence, Saint Sava finished his Zakonopravilo in 1219.

Zakonopravilo was accepted in Bulgaria, Romania and Russia. It was printed in Moscow in the 17th century. So, Roman-Byzantine law was transplanting among East Europe through Zakonopravilo. In Serbia, it was considered as the code of the divine law and it was implemented into Dušan's code (Serbian: Dušanov zakonik)[10] (1349 and 1354). It was the only code among Serbs in the time of the Ottoman reign.

During the Serbian Revolution (1804) priest Mateja Nenadović established Zakonopravilo as the code of the liberated Serbia. It was also implemented in Serbian civil code (1844). Zakonopravilo is still used in the Serbian Orthodox Church as the highest church code.

East Syriac tradition

Nomocanons of the Church of the East by author are:

- Ishoʿbokht (8th century), author of the Composition on the Laws (Persian)

- Gabriel of Basra (late 9th century), author of the Collection of Judgements (Syriac)

- Eliya ibn ʿUbaid (early 10th century), author of the Nomocanon Arabicus (Arabic)

- Ibn al-Ṭayyib (11th century), author of the Law of Christianity (Arabic)

- ʿAbdishoʿ bar Brikha (d. 1318), author of the Nomokanon (Syriac)

See also

References

- For the canonical collection see Voellus and Henri Justel, "Bibliotheca juris canonici", Paris, 1661, II, 449 sqq.; for the 87 chapters, Pitra, "Juris ecclesiastici Græcorum historia et monumenta", Rome, 1864, II, 385)

- Voellus and Justellus, op. cit., II, 603.

- Fr. Justin Taylor, essay "Canon Law in the Age of the Fathers" (published in Jordan Hite, T.O.R., & Daniel J. Ward, O.S.B., "Readings, Cases, Materials in Canon Law: A Textbook for Ministerial Students, Revised Edition" (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1990), p. 61

- "Photian Synods of Constantinople (861, 867, 879)". The Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1908. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- Nomocanon with Balsamon's commentary in Voellus and Justellus, II, 815; P. G., CIV, 441.

- P. G., loc. cit.; Beveridge, "Synodicon", Oxford, 1672.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-05-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "S. P. Scott: The Civil Law". Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2010-05-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-08-03. Retrieved 2010-07-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Sources

- The entry of the Slavs into Christendom

- The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century

![]()