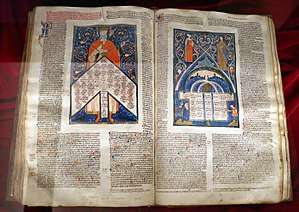

Decretales Gregorii IX

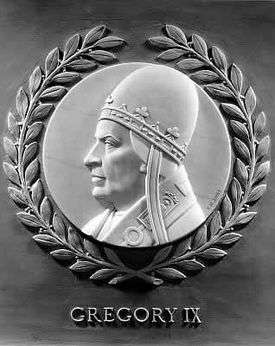

The Decretals of Gregory IX (Latin, Decretales Gregorii IX), also collectively called the Liber extra, are an important source of medieval Canon Law. In 1230, Pope Gregory IX ordered his chaplain and confessor, St. Raymond of Penyafort, a Dominican, to form a new canonical collection destined to replace all former collections. It has been said that the pope by this measure wished especially to emphasize his power over the Universal Church.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Canon law of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

Jus antiquum (c. 33-1140)

Jus novum (c. 1140-1563) Jus novissimum (c. 1563-1918) Jus codicis (1918-present) Other |

|

Sacraments

Sacred places

Sacred times |

|

|

Supreme authority, particular churches, and canonical structures Supreme authority of the Church

Supra-diocesan/eparchal structures

|

|

|

Temporal goods (property) |

|

Canonical documents |

|

Procedural law Pars statica (tribunals & ministers/parties)

Pars dynamica (trial procedure)

Election of the Roman Pontiff |

|

Legal practice and scholarship

Academic degrees Journals and Professional Societies Faculties of canon law

Canonists |

|

|

Political circumstances

The papacy had arrived at the zenith of its power. Moreover, a pope less favourably circumstanced probably would not have thought of so important a measure. Nevertheless, the utility of a new collection was so evident that there may be no other motives than those the pope gives in the Bull "Rex pacificus" of 5 September 1234, viz., the inconvenience of recurring to several collections containing decisions most diverse and sometimes contradictory, exhibiting in some cases gaps and in others tedious length; moreover, on several matters the legislation was uncertain.[1]

Work of St. Raymond

The Quinque compilationes antiquæ was a series of five of these collections of pontifical legislation from the Decretum of Gratian (c. 1150) to the pontificate of Honorius III (1150-1227). Raymond executed the work in about four years, and followed in it the method of the Quinque compilationes antiquæ. He borrowed from them the order of the subject-matter, the division into five books, of the books into titles and of the titles into chapters. Of the 1971 chapters the Decretals of Gregory IX contain, 1771 are from the Quinque compilationes antiquæ, 191 are from Gregory IX himself, seven from decretals of Innocent III not inserted in the former collections, and two are of unknown origin. They are arranged, generally, according to the order of the ancient collections, i.e., each title opens with the chapters of the first collection, followed by those of the second, and so on in regular order. Next come those of Innocent III, and finally those of Gregory IX. Almost all the rubrics, or headings of the titles, have also been borrowed from these collections, but several have been modified as regards detail. This method considerably lightened St. Raymond's task.[1]

Editorial work

However, he did more than simply compile the documents of former collections. He left out 383 decisions, modified several others, omitted parts when he considered it prudent to do so, filled up the gaps, and to render his collection complete and concordant, cleared up doubtful points of the ancient ecclesiastical law by adding some new decretals. He indicated by the words et infra the passages excised by him in the former collections. They are called partes decisae. The new compilation bore no special title, but was called "Decretales Gregorii IX" or sometimes "Compilatio sexta", i. e. the sixth collection with reference to the "Quinque compilationes antiquæ". It was also called "Collectio seu liber extra", i. e. the collection of the laws not contained (vagantes extra) in the "Decretum" of Gratian. Hence the custom of denoting this collection by the letter X (i.e. extra, here not the Roman numeral for ten).[1]

Quotations

Quotations from this collection are made by indicating the number of the chapter, the name the work goes by (X), the number of the book, and that of the title. Usually the heading of the title and sometimes the first words of the chapter are quoted; for instance, "c. 3, X, III, 23", or "c. Odoardus, X, De solutionibus, HI, 23", refers to the third chapter, commencing with the word Odoardus, in the Decretals of Gregory IX, book III, title 23, which is entitled "De solutionibus". If the number of the chapter or of the title is not indicated it will easily be learned on consulting the alphabetical indexes of the rubrics and of the introductory words of the chapters, which are to be found in all editions of the "Corpus Juris Canonici". Gregory IX sent this new collection to the Universities of Bologna and Paris, and declared, by the Bull "Rex pacificus" of 5 September 1234, that this compilation was the official code of the canon law.

Force of law

All its decisions had the force of canon law whether they were authentic or not, whatever the juridical value of the texts considered in themselves, and whatsoever the original text. It is a unique collection; all its decisions were simultaneously promulgated, and are equally obligatory, even if they appear to contain, or if in fact they do contain, antinomies, i. e. contradictions. In this peculiar case it is not possible to overcome the difficulty by recourse to the principle that a law of later date abrogates that of an earlier period. Finally, it is an exclusive collection, i.e. it abrogates all the collections, even the official ones, of a later date than the "Decretum" of Gratian. Some authors (Schulte, Launin) maintain that Gregory IX abrogated even those laws prior to Gratian's time that the latter had not included in his "Decretum", but others contest this opinion.[2]

Differences with modern codes

The Decretals of Gregory IX differ widely from modern codes. Instead of containing in one concise statement a legislative decision, they generally start with an account of a controversy, the allegations of the parties in dispute, and a demand or the solution of the question; this species facti or the pars historica has no juridical value whatever. The enacting part of the chapter (pars dispositiva) alone has the force of law; it contains the solution of the case or the statement of the rule of conduct. The rubrics of the titles have the force of law when their sense is complete, as for instance, Ne sede vacante aliquid innovetur (Let there be no innovation while the see is vacant), because the headings form an integral part of the official code of the laws. However, they ought always to be interpreted according to the decisions contained in the chapters.

Historical indications

The historical indications concerning each chapter are often far from being exact, even since they were corrected in the Roman edition of 1582. It may be regretted that St. Raymond did not have recourse to the original documents themselves, of which a large number must have been at his disposal. The summaries (summaria) that precede the chapters are the work of the canonists, and may assist in the elucidation of the text. The partes decisae are sometimes of like use, but never when these parts were designedly omitted from a desire to extinguish their legal force or because they contain decisions irreconcilable with the actual text of the law.

Glosses

Like the former canonical collections, the Decretals of Gregory IX were soon glossed. It was customary to add to the manuscript copies textual explanations written between the lines (glossa interlinearis) and on the margin of the page (glossa marginalis). Explanations of the subject-matter were also added. The most ancient glossarist of the Decretals of Gregory IX is Vincent of Spain; then follow Godefridus de Trano (died 1245), Bonaguida Aretinus (thirteenth century) and Bernard of Botone or Parmensis (died 1263), the author of the "Glossa ordinaria", i.e., of that gloss to which authoritative credence was generally given. At a later date some extracts were added to the "Glossa ordinaria" from the "Novella sive commentarius in decretales epistolas Gregorii IX" by Giovanni d'Andrea (Johannes Andreæ).

Printed publication

After the invention of printing, the Decretals of Gregory IX were first published at Strasburg from the press of Heinrich Eggesteyn. Among the numerous editions that followed, special mention must be made of that published in 1582 (in dibus populi romani) by order of Gregory XIII. The text of this edition, revised by the Correctores Romani, a pontifical commission established for the revision of the text of the "Corpus Juris", had the force of canon law, even when it differed from that of St. Raymond. It was forbidden to introduce any change into that text (Papal Brief "Cum pro munere", 1 July 1580). Among the other editions, mention may be made of that by Le Conte (Antwerp, 1570), of prior date to the Roman edition and containing the partes decis; that of the brothers Pithou (Paris, 1687); that of Böhmer (Halle, 1747), which did not reproduce the text of the Roman edition and was in its textual criticism more audacious than happy; the edition of Richter;[3] and that of Friedberg (Leipzig, 1879-1881). All these authors added critical notes and the partes decis.

Commentators

To indicate the principal commentators on the Decretals would mean writing a history of canon law in the Middle Ages. Important canonists include Innocent IV (died 1254), Enrico de Segusio or Hostiensis (died 1271), the "Abbas antiquus" (thirteenth century), Johannes Andreæ, Baldus de Ubaldis (died 1400), Petrus de Ancharano (died 1416), Franciscus de Zabarellis (died 1417), Dominicus a Sancto Geminiano (fifteenth century), Joannes de Imola (died 1436) and Nicolò Tudesco also called the "Abbas Siculus", or "Modernus", or "Panormitanus" (died 1453). Among the modern commentators, Manuel Gonzalez Tellez and Fagnanus may be consulted advantageously for the interpretation of the text of the Decretals. The Decretals of Gregory IX remain the basis of canon law so far as it has not been modified by subsequent collections and by the general laws of the Church (see Corpus Juris Canonici).

References

- "Van Hove, Alphonse. "Papal Decretals." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 9 Sept. 2014". Archived from the original on 2013-01-20. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- von Scherer, Schneider, Franz Xavier Wernz, etc.

- (Leipzig, 1839)

External links

From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress: