Nizar ibn al-Mustansir

Abū Manṣūr Nizār ibn al-Mustanṣir (Arabic: أبو منصور نزار بن المستنصر; 1045–1095) was a Fatimid prince, and the oldest son of the eighth Fatimid caliph and Isma'ili imam, al-Mustansir. When his father died in December 1094, the military strongman, al-Afdal Shahanshah, raised Nizar's younger brother al-Musta'li to the throne in Cairo, bypassing the claims of Nizar and other older sons of al-Mustansir. Nizar escaped Cairo, rebelled and seized Alexandria, where he reigned as caliph with the regnal name al-Muṣṭafā li-Dīn Allāh (المصطفى لدين الله). In late 1095 he was defeated and taken prisoner to Cairo, where he was killed by immurement. Many Isma'ilis, especially in Persia, who rejected al-Musta'li's imamate and considered Nizar as the rightful imam, split off from the Fatimid regime and founded the Nizari branch of Isma'ilism, with their own line of imams who claimed descent from Nizar that continues to this day. Later during the 12th century some of Nizar's actual or claimed descendants tried, without success, to seize the throne from the Fatimid caliphs.

Abu Mansur Nizar al-Mustafa li-Din Allah | |

|---|---|

| Born | 26 September 1045 Cairo, Egypt |

| Died | November/December 1095 Cairo, Egypt |

| Cause of death | Immurement |

| Title | Imam of Nizari Isma'ilism |

| Term | 1094–1095 |

| Predecessor | al-Mustansir Billah |

| Successor | Ali al-Hadi (in occultation) |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Family | Fatimid dynasty |

Life

Nizar was born on 26 September 1045 to the ruling Fatimid imam–caliph, al-Mustansir (r. 1036–1094).[1] At that time, al-Mustansir was around 15 years old and had already been on the throne for ten years.[2] Nizar was most likely the eldest son of the caliph, although another son named Abdallah is sometimes listed as the senior of al-Mustansir's sons.[2]

About 1068, as internal turmoils led the dynasty close to collapse, al-Mustansir dispersed his sons throughout his territories as a safeguard; although Nizar is not mentioned by name except in later versions of this story, he was likely involved in this scheme as well. This flight lasted at least until the Armenian commander Badr al-Jamali assumed power in 1073 as vizier and quasi-dictator and restored order in Egypt.[3] In 1094, shortly before his death, Badr was succeeded by his son, al-Afdal Shahanshah.[4]

Disputed succession

As the oldest son, Nizar was apparently considered to be his father's most likely successor, as was the custom;[5] indeed, historians often state that Nizar had been his father's designated (naṣṣ) successor.[lower-alpha 1][7][8] However, no definite designation of Nizar as heir seems to have taken place by the time of al-Mustansir's death.[5][9] The Mamluk-era historian al-Maqrizi writes that this was due to the machinations of al-Afdal, who had prevented al-Mustansir from making his choice of Nizar public because of a deep-seated enmity between the two men.[10] Reportedly, the vizier had once tried to enter the palace on horseback, whereupon Nizar yelled at him to dismount and called him a "dirty Armenian". Since then, the two had been bitter enemies, with al-Afdal obstructing Nizar's activities and demoting his servants, while at the same time winning the army's commanders over to his cause. Only one of them, the Berber Muhammad ibn Masal al-Lukki, is said to have remained loyal to Nizar, because he had promised to appoint him vizier instead of al-Afdal.[10][11]

Indeed, when al-Mustansir died in December 1094, al-Afdal, who himself had only recently succeeded his own father, raised a much younger[lower-alpha 2] half-brother of Nizar, al-Musta'li to the throne and the imamate. Furthermore, Al-Musta'li, who had just married al-Afdal's sister, was completely dependent on al-Afdal for his accession. This made him a compliant figurehead who was unlikely to threaten al-Afdal's recent, and therefore as yet fragile, hold on power by attempting to appoint another to the vizierate.[7][13][14] Some later accounts hold that al-Musta'li's accession was indeed legitimate, by asserting that on the wedding banquet, or on his deathbed, al-Mustansir had chosen him as his heir, and that one of al-Mustansir's sisters is said to have been called to him privately and received al-Musta'li's nomination as a bequest.[5][15] Modern historians, such as Farhad Daftary, believe that these stories are most likely attempts to justify and retroactively legitimize what was in effect a coup d'état by al-Afdal.[7]

However, al-Maqrizi also includes a different narrative that casts doubt on whether al-Afdal's move was really a carefully prepared coup. When al-Afdal summoned three of al-Mustansir's sons—Nizar, Abdallah, and Isma'il, apparently the most prominent among the caliph's progeny—to the palace to do homage to al-Musta'li, who had been seated on the throne, they each refused. Not only did they reject al-Musta'li, but each of them claimed that al-Mustansir had chosen him as his successor. Nizar claimed that he had a written document to this effect.[16][17] This refusal apparently took al-Afdal completely by surprise. The brothers were allowed to leave the palace; but while Abdallah and Isma'il made for a nearby mosque, Nizar fled Cairo immediately.[16][17] To add to the confusion, having learned of al-Mustansir's passing, Baraqat, the chief missionary (dāʿı̄) of Cairo (the head of the Isma'ili religious establishment) proclaimed Abdallah as caliph with the regnal name al-Muwaffaq.[18] However, al-Afdal soon regained control. Baraqat was arrested (and later executed), Abdallah and Isma'il were placed under surveillance and eventually acknowledged al-Musta'li, and a grand assembly of officials was held, which acclaimed al-Musta'li as imam and caliph.[10]

Rebellion and death

In the meantime, Nizar fled to Alexandria with a few followers. The local governor, a Turk named Nasr al-Dawla Aftakin, opposed al-Afdal, so Nizar was quickly able to gain his support. He also won over the local qāḍī ("magistrate"), the inhabitants and the surrounding Arab tribes to his cause. He then rose in revolt and proclaimed himself imam and caliph with the title of al-Mustafa li-Din Allah ("the Chosen One for God's Religion").[1][9][19][20] A gold dinar of Nizar, bearing this title, was discovered in 1994, attesting to his assumption of the caliphal title and the minting of coinage with it.[19] According to the historian Paul E. Walker, the speed with which Nizar gained support, and some other stories narrated in al-Maqrizi, suggest the existence of a relatively large faction that expected or wanted him to succeed al-Mustansir.[20]

Nizar's revolt was initially successful: al-Afdal's attack on Alexandria in February 1095 was easily repulsed, and Nizar's forces raided up to the outskirts of Cairo. Over the next months, however, al-Afdal managed to win back the allegiance of the Arab tribes with bribes and gifts. Weakened, Nizar's forces were pushed back to Alexandria, which was placed under siege. In November, Ibn Masal abandoned the city with most of the remaining treasure, forcing Aftakin and Nizar to surrender against a writ of safety (amān). Both were taken back to Cairo, where Nizar was immured alive and Aftakin was executed.[lower-alpha 3][1][9][19][20]

Nizari schism

Despite problems with succession arrangements before, the events surrounding al-Musta'li's accession was the first time that rival members of the Fatimid dynasty had actually fought over it.[22] This was of momentous importance since, given the pivotal role of the imam in the Isma'ili faith, the issue of succession was not merely a matter of political intrigue, but also intensely religious. In the words of the historian Samuel Miklos Stern, "on it depended the continuity of institutional religion as well as the personal salvation of the believer".[23] To the Isma'ili faithful, writes Stern, it was "not so much the person of the claimant that weighed with his followers; they were not moved by any superior merits of Nizar as a ruler [...] it was the divine right personified in the legitimate heir that counted".[23]

As a result, the events of 1094–1095 caused a bitter and permanent schism in the Isma'ili movement, that continues to this day.[22][24] While al-Musta'li was recognized by the Fatimid establishment and the official Isma'ili daʿwa, as well as the Isma'ili communities dependent on it in Syria and Yemen, most of the Isma'ili communities in the wider Middle East, and especially Persia and Iraq, rejected it. Whether out of genuine conviction, or as a convenient excuse to rid himself of Cairo's tutelage, Hassan-i Sabbah, the chief Isma'ili leader in Persia, swiftly recognized Nizar's rights to the imamate, severed relations with Cairo, and set up his own independent daʿwa (the daʿwa jadīda, "new calling"). This marked the permanent and enduring split of the Isma'ili movement into the rival "Musta'li" and "Nizari" branches.[25][26]

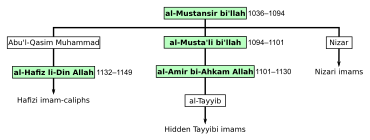

Hassan-i Sabbah founded the Nizari Order of Assassins, which was responsible for the assassination of al-Afdal in 1121,[27][28] and of al-Musta'li's son and successor al-Amir bi-Ahkam Allah (who was also al-Afdal's nephew and son-in-law) in October 1130.[28][29] This led to a succession of coups and crises that heralded the final decline, and eventual collapse, of the Fatimid state.[30] In 1130–1131 the dynasty was temporarily abolished outright by al-Afdal's son Kutayfat, before Nizar's nephew Abd al-Majid, in the absence of a direct heir of al-Amir, assumed the imamate and the caliphate as al-Hafiz li-Din Allah in January 1132.[31][32][33] Al-Hafiz' succession led to another schism in Isma'ilism, between those Musta'lis who accepted al-Hafiz' succession (the "Hafizis") and those who did not, upholding instead the imamate of al-Amir's infant son al-Tayyib (the "Tayyibis").[34][35] Whereas Nizari Isma'ilism survived in Persia and Syria, and Tayyibi Isma'ilism in Yemen and India, the Hafizi sect, closely associated with the Fatimid state, did not long survive the latter's final abolition by Saladin in 1171.[36]

Descendants and succession

Contemporary sources attest that Nizar had sons.[37] At least one of them, al-Husayn, fled with other members of the dynasty (including three of Nizar's brothers, Muhammad, Isma'il, and Tahir) from Egypt to the western Maghreb in 1095, where they formed a sort of opposition in exile to the new regime in Cairo.[9][20] In 1132, following the highly irregular accession of al-Hafiz, al-Husayn tried to return to Egypt. He managed to raise an army, but al-Hafiz successfully suborned his commanders and had him killed.[38][39] In 1149, al-Hafiz had to confront a similar threat by a purported son of Nizar. He also managed to recruit a large following among the Berbers, but he was also killed when the Fatimid caliph bribed his commanders.[40][41] The last revolt by a Nizari claimant was by al-Husayn's son Muhammad in 1162, but he was lured with false promises and executed by the vizier Tala'i ibn Ruzzik.[40][42] There are indications that another of Nizar's sons, named Muhammad, had left for Yemen.[40]

None of these sons had been designated as successor by Nizar, however, so they lacked the legitimacy to become imam after him. This raised an acute problem for the Nizari faithful, as the line of divinely ordained imams could not possibly be broken.[43] At first, some Nizaris held that Nizar was not dead would return as the Mahdi (or at least with him).[1] Indeed, coinage from Alamut Castle, the centre of Hassan's nascent Nizari Isma'ili state in central Persia, was minted with Nizar's regnal name of al-Mustafa li-Din Allah until 1162.[43] No imam was named publicly at Alamut until then, and Hassan-i Sabbah and his two immediate successors ruled instead as dāʿı̄s and ḥujjas ("seals, proofs"), representatives of the absent imam. However, the Nizaris soon came to believe that a son or grandson of Nizar had been smuggled out of Egypt and brought to Alamut. He and his two successors—Ali al-Hadi, Muhammad (I) al-Muhtadi, and Hasan (I) al-Qahir[44]—are held to have been imams in occultation until 1162, when with Hassan II, the imams reappeared in public and took up the reins of the Nizari state.[45] The current head of Nizari Islam, the Aga Khan, claims descent in direct line from Nizar via Hassan II.[21]

Footnotes

- The concept of naṣṣ is central to the early Shi'a, and particularly the Isma'ili, concept of the imamate, but it also presented complications: as the imam possessed God's infallibility (ʿiṣma), he could not possibly err, especially in the selection of his heir. Appointed heirs predeceasing their fathers were a source of considerable embarrassment, and therefore, while an heir might be clearly favoured during his father's reign, naṣṣ was often withheld until shortly before the ruling imam's death, proclaimed in the latter's testament, or left as a bequest with a third party.[6]

- Indeed, al-Musta'li was apparently the youngest of all of al-Mustansir's sons.[5][12]

- In a letter sent to the Yemeni queen Arwa al-Sulayhi announcing his accession, al-Musta'li gives the "official" version of events as follows: Like the other sons of al-Mustansir, Nizar had at first accepted his imamate and paid him homage, before being moved by greed and envy to revolt. The events up to the capitulation of Alexandria are reported in some detail, but nothing is mentioned of Nizar's fate or that of Aftakin.[21]

References

- Gibb 1995, p. 83.

- Walker 1995, p. 250.

- Walker 1995, pp. 250–251.

- Halm 2014, pp. 86–87.

- Gibb 1993, p. 725.

- Walker 1995, pp. 240–242.

- Daftary 2007, p. 241.

- Brett 2017, p. 228.

- Halm 2014, p. 90.

- Walker 1995, p. 254.

- Halm 2014, p. 89.

- Walker 1995, p. 251.

- Walker 1995, p. 252.

- Brett 2017, pp. 228–229.

- Walker 1995, pp. 252, 257.

- Halm 2014, p. 88.

- Walker 1995, p. 253.

- Walker 1995, pp. 253–254.

- Daftary 2007, p. 242.

- Walker 1995, p. 255.

- Halm 2014, p. 91.

- Walker 1995, p. 248.

- Stern 1951, p. 194.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 242–243.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 242–243, 324–325.

- Brett 2017, pp. 229–230.

- Brett 2017, p. 252.

- Daftary 2007, p. 244.

- Brett 2017, pp. 233–234, 261.

- Daftary 2007, p. 246.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 247–248.

- Brett 2017, pp. 263–265.

- Halm 2014, pp. 178–183.

- Brett 2017, pp. 265–266.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 248, 264.

- Daftary 2007, p. 248.

- Daftary 2007, p. 325.

- Walker 1995, pp. 255–256.

- Halm 2014, pp. 186–187.

- Walker 1995, p. 256.

- Halm 2014, pp. 221–222.

- Halm 2014, p. 249.

- Daftary 2007, p. 326.

- Daftary 2007, p. 509.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 301–302, 326, 509.

Sources

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. The Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4076-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1993). "al- Mustaʿlī bi'llāh". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 725. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1995). "Nizār b. al-Mustanṣir". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 83. ISBN 90-04-09834-8.

- Halm, Heinz (2014). Kalifen und Assassinen: Ägypten und der vordere Orient zur Zeit der ersten Kreuzzüge, 1074–1171 [Caliphs and Assassins: Egypt and the Near East at the Time of the First Crusades, 1074–1171] (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-66163-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stern, S. M. (1951). "The Succession to the Fatimid Imam al-Āmir, the Claims of the Later Fatimids to the Imamate, and the Rise of Ṭayyibī Ismailism". Oriens. 4 (2): 193–255. doi:10.2307/1579511. JSTOR 1579511.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walker, Paul E. (1995). "Succession to Rule in the Shiite Caliphate". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 32: 239–264. doi:10.2307/40000841. JSTOR 40000841.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Ismaili History: AL-NIZAR (487-490/1095-1097), The Heritage Society.

Nizar ibn al-Mustansir Fatimid dynasty Born: 1045 Died: 1095 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by al-Mustansir |

Fatimid Caliph (claimant in Alexandria) 1095 |

Succeeded by al-Musta'li |

| Shia Islam titles | ||

| Preceded by al-Mustansir |

19th Imam of Nizari Isma'ilism 1094–1095 |

Succeeded by Ali al-Hadi ibn Nizar (in occultation) |