Abu Tahir al-Jannabi

Abu Tahir Sulayman al-Jannabi (Arabic: ابو طاهر سلیمان الجنّابي, romanized: Abū Tāhir Sulaymān al-Jannābī) was an Iranian[1] warlord and the ruler of the Qarmatian state in Bahrayn (Eastern Arabia), who in 930 led the sacking of Mecca.

| Abu Tahir Sulayman al-Jannabi | |

|---|---|

| Ruler of the Qarmatian state in Bahrayn | |

| Reign | 923–944 |

| Coronation | 923 |

| Predecessor | Abu'l-Qasim Sa'id |

| Successor | Succeeded by his 3 surviving brothers and nephews |

| Born | c. 906 Bahrayn |

| Died | 944 Bahrayn |

A younger son of Abu Sa'id al-Jannabi, the founder of the Qarmatian state, Abu Tahir became leader of the state in 923, after ousting his older brother Abu'l-Qasim Sa'id.[2] He immediately began an expansionist phase, raiding Basra that year. He raided Kufa in 927, defeating an Abbasid army in the process, and threatened the Abbasid capital Baghdad in 928 before pillaging much of Iraq when he could not gain entry to the city.[3]

In 930, he led the Qarmatians' most notorious attack when he pillaged Mecca and desecrated Islam's most sacred sites. Unable to gain entry to the city initially, Abu Tahir called upon the right of all Muslims to enter the city and gave his oath that he came in peace. Once inside the city walls the Qarmatian army set about massacring the pilgrims, taunting them with verses of the Koran as they did so.[4] The bodies of the pilgrims were left to rot in the streets or thrown down the Well of Zamzam. The Kaaba was looted, with Abū Tāhir taking personal possession of the Black Stone and taking it away to al-Hasa.

Early life

Abu Tahir's father Abu Sa'id was a tribal leader who had initiated the militarization of the Qarmatians.[5] Abu Sa'id began preaching against Sunni Islam around 890[6] after being taught by his mentor Hamdan Qarmat, a native of Kufa, from whose name the Qarmatian sect is derived.[6]

Abu Sa'id started off plundering caravans, traders and Persian hajj pilgrims en route to Mecca before gathering a large following.[5] The Qarmatians soon mobilized an army and set out to lay siege to Basra. However, the governor of Basra learned of their preparations and informed the Abbasid Caliph, al-Muktafi, in Baghdad. The Caliph sent the general Abbas bin Umar to save Basra,[5] but Abbas was defeated and his men executed and the Qarmatian siege was successful in capturing the city.[5]

Rise to power

Most Arabic sources agree that Abu Sa'id appointed his oldest son, Abu'l-Qasim Sa'id, as his heir, and that Abu Tahir led a revolt against him and usurped his power.[7] Another tradition, by the Kufan anti-Isma'ili polemicist Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Rizam al-Ta'i, on the other hand reports that Abu Sa'id always intended for Abu Tahir to succeed him, and had named Sa'id only as regent. According to this view, Sa'id handed over power to his younger brother (who was then barely ten years old) in 917/918. This report chimes with the story in Ibn Hawqal that Abu Sa'id ha instructed his other sons to obey the youngest.[7] Indeed, it is likely that power was nominally invested among all of Abu Sa'id's sons, with Abu Tahir being the dominant among them.[8] Whatever the true events, Abu'l-Qasim was not executed, but lived until his death in 972.[7]

Early reign

Soon after succeeding al-Muktafi, Caliph al-Muqtadir recaptured Basra and ordered the re-fortification of the city. Abu Tahir successfully laid siege to the city once more, defeating the Abbasid army. After capturing Basra the Qarmatians proceeded to loot it and then withdrew.[5] Abu Tahir returned again and ravaged it totally, destroying the grand mosque and reducing the marketplace to ashes.[5] He ruled Bahrayn successfully during this time and corresponded with local and foreign rulers as far as north Africa, but continued successfully fighting off assaults from the Persians, who were allied with the Caliph in Baghdad.[5]

Conquests

Abu Tahir began to frequently raid Muslim pilgrims, reaching as far as the Hijaz region. On one of his raids he succeeded in capturing the Abbasid commander Abu'l-Haija ibn Hamdun. In 926 he led his army deep into Abbasid Iraq, reaching as far north as Kufa, forcing the Abbasids to pay large sums of money in for him to leave the city in peace. On his way home he ravaged the outskirts of Kufa anyway.[5] On his return, Abu Tahir began building palaces in the city of Ahsa, not only for himself but for his fellows, and declared the city his permanent capital.[5] In 928 Caliph al-Muqtadir felt confident enough to once again confront Abu Tahir, calling in his generals Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj from Azerbaijan, Mu'nis al-Muzaffar and Harun.[5] After a heavy battle all were beaten and driven back to Baghdad.[5] Abu Tahir destroyed Jazirah Province as a final warning to the Abbasids and returned to Ahsa.[5]

Abu Tahir thought that he had identified the Mahdi as a young Persian prisoner from Isfahan by the name of Abu'l-Fadl al-Isfahani, who claimed to be the descendant of the Sassanid Persian kings.[9][10][11][12][12][13] Al-Isfahani had been brought back to Bahrayn from the Qarmatians' raid into Iraq in 928.[14] In 931, Abu Tahir turned over the state to this Mahdi-Caliph, who instituted the worship of fire and the burning of religious books during an eighty-day rule. His reign culminated in the execution of members of Bahrayn's notable families, including members of Abu Tahir's family.[15] Fearing for his own life, Abu Tahir announced that he had been wrong and denounced the al-Isfahani as a false Mahdi. Begging forgiveness from the other notables, Abu Tahir had him executed.[16]

Invasion of Mecca

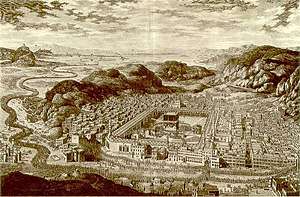

In 930, Abu Tahir led the Qarmatians' most infamous attack when he pillaged Mecca and desecrated Islam's most sacred sites. Unable to gain entry to the city initially, he called upon the right of all Muslims to enter the city and gave his oath that he came in peace. Once inside the city walls the Qarmatian army set about massacring the pilgrims, riding their horses into Masjid al-Haram and charging the praying pilgrims. While killing pilgrims, he was taunting them with verses of the Koran as they did so[4], and verses of poetry: "I am by God, and by God I am ... he creates creation, and I destroy them".

Their victims allegedly numbered around some thirty thousand. The bodies of the pilgrims were left to rot in the streets, or thrown down the Well of Zamzam, filling it. The Kaaba was looted, houses were plundered, slaves seized. Abū Tāhir and his army removed the Black Stone and took it away to al-Hasa. For 21 years, it was in his possession, and it is reported that he daily desecrated it with urine.[6]

The attack on Mecca symbolized the Qarmatians' break with the Sunni world; it was believed to have been aimed to prompt the appearance of the Mahdi who would bring about the final cycle of the world and end the era of Islam.[16]

Final years and death

Abu Tahir resumed the reins of the Qarmatian state and again began attacks on pilgrims crossing Arabia. Attempts by the Abbasids and Fatimids to persuade him to return the Black Stone were rejected.

He died in 944, around the age of 38, and was succeeded by his three surviving sons and nephews.[17]

See also

- History of Bahrain

- 1979 Grand Mosque seizure

References

- Carra de Vaux & Hodgson 1965, p. 452.

- Daftary 1990, p. 160.

- Halm 1996, p. 255.

- Halm 1996, pp. 255 f..

- Akbar Shah Khan Najibabadi (2001). Salafi, Muhammad Tahir (ed.). The History of Islam. Volume 2. Darussalam. ISBN 978-9960-892-93-1.

- Wynbrandt, James (2004). A Brief History of Saudi Arabia. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0830-8.

- Madelung 1996, p. 37.

- Madelung 1996, p. 39.

- Imagining the End: Visions of Apocalypse By Abbas Amanat, Magnus Thorkell - Page 123

- Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam - Page 26 by Delia Cortese, Simonetta Calderini

- Early Philosophical Shiism: The Ismaili Neoplatonism of Abū Yaʻqūb Al-Sijistānī - Page 161 by Paul Ernest Walke

- The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy by Yuri Stoyanov

- Classical Islam: A History, 600–1258 - Page 113 by Gustave Edmund Von Grunebaum

- Halm 1996, p. 257.

- Farhad Daftary, The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma'ilis, IB Tauris, 1994, p21

- Daftary 1990, p. 162.

- Halm 1996, p. 383.

Sources

- Canard, M. (1965). "al-D̲j̲annābī, Abū Ṭāhir". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 452–454. OCLC 495469475.

- Carra de Vaux, B. & Hodgson, M. G. S. (1965). "al-D̲j̲annābī, Abū Saʿīd Ḥasan b. Bahrām". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 452. OCLC 495469475.

- Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37019-6.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1996). "The Fatimids and the Qarmatīs of Bahrayn". In Daftary, Farhad (ed.). Mediaeval Isma'ili History and Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–73. ISBN 978-0-521-00310-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halm, Heinz (1996). The Empire of the Mahdi: The Rise of the Fatimids. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10056-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)