Nepenthes benstonei

Nepenthes benstonei /nɪˈpɛnθiːz bɛnˈstoʊniaɪ/ is a tropical pitcher plant endemic to Peninsular Malaysia, where it grows at elevations of 150–1350 m above sea level.[2][10] The specific epithet benstonei honours botanist Benjamin Clemens Stone, who was one of the first to collect the species.[1]

| Nepenthes benstonei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Upper pitchers of Nepenthes benstonei from Bukit Bakar | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Nepenthaceae |

| Genus: | Nepenthes |

| Species: | N. benstonei |

| Binomial name | |

| Nepenthes benstonei | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Botanical history

In their 1997 monograph, "A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae)", Matthew Jebb and Martin Cheek tentatively referred specimens collected from Bukit Bakar, near Macang, Kelantan, to N. sanguinea.[7] These were Stone & Chin 15238, deposited at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia near Kuala Lumpur (KLU), and Shah & Shukor 3168, also held at KLU as well as the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia in Kepong (KEP). They noted that the plants exhibited some unusual morphological features, such as larger leaves and decurrent, almost petiolate leaf bases, suggesting that they might represent an as-yet undescribed taxon.[7]

Field studies confirmed that the taxon represented a separate species, and it was formally described as N. benstonei in 1999 by Charles Clarke.[1][11]

The holotype of N. benstonei, Clarke s.n., was collected by Charles Clarke on 24 July 1998, on Bukit Bakar in Kelantan at an altitude of between 450 and 550 m. It is deposited at the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia in Kepong (KEP). Isotypes are held at Herbarium Bogoriense (BO), the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (K), the National Herbarium of the Netherlands in Leiden (L), the Forest Department in Sandakan (SAN), and the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SING).[2][12]

Ridley 16097

Although only described towards the very end of the twentieth century, N. benstonei was probably first collected in July 1911 by Henry Nicholas Ridley on Mount Tahan in Pahang. The Ridley 16097 series comprises three herbarium sheets: one deposited at the Singapore herbarium and two at Kew. The former consists of a climbing stem fragment with two upper pitchers and two female inflorescences. The two sheets at Kew are barcoded K000651565 (climbing stem with immature female inflorescence but no pitchers) and K000651564 (climbing stem with upper pitchers), and differ significantly in morphology.[2] Ridley referred the Ridley 16097 material to N. singalana.[2]

For his seminal monograph of 1928, "The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies", B. H. Danser examined the sheet of Ridley 16097 held in Singapore, lumping it with the variable N. alata from the Philippines.[3] Danser briefly mentioned this specimen in his discussion of N. alata:[3]

The specimen recorded by me from the Malay Peninsula deviates more [from N. alata], especially by the long, narrow inflorescence and 2-flowered pedicels, but also in the Philippines and Sumatra forms with 2-flowered pedicels have been found (Ramos 14650, Lörzing 11603).

Danser also treated N. eustachya from Sumatra in synonymy with N. alata, giving rise to a taxon with a puzzling geographical distribution: widespread across Sumatra and the Philippines, apparently very rare in the Malay Peninsula (Ridley 16097 being the sole record), and completely unknown from Borneo and the other major islands of the Malay Archipelago.[3][12]

In 1990, Ruth Kiew identified Ridley 16097 as belonging to N. gracillima. Kiew explained the apparent near-absence of N. alata from Peninsular Malaysia as follows:[6]

Why has this species not been recollected since 1911 in spite of several botanical expeditions to G. Tahan since then? The answer is quite simple, Ridley's specimen (16097) actually belongs to N. gracillima. Although N. alata Blanco is superficially similar to N. gracillima in its narrow leaf blade which has an attenuate base, the pitchers of these two species are distinct. Those of N. alata are broader (about 4 cm wide) and are distinctly bulbous towards the base compared with the very slender, non-bulbous pitchers of N. gracillima that are 1.5 to 3 cm wide. Nor does the G. Tahan specimen have truly petiolate leaves - its leaf base is narrow and has rolled up during drying. Ridley's specimen from G. Tahan determined by Danser as N. alata bears pitchers typical of N. gracillima and examination of the Tahan population in the field leaves no doubt that it belongs to this species.

Jebb and Cheek supported this interpretation in their 1997 monograph, "A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae)",[7] and in their 2001 treatment for Flora Malesiana, "Nepenthaceae".[8] They also restored N. eustachya as a separate species, making N. alata a Philippine endemic once again — a circumscription that has been accepted by subsequent authors.[12][13]

However, in his 2001 book, Nepenthes of Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia, Charles Clarke disagreed with Kiew's identification of Ridley 16097 as N. gracillima. He noted that the inflorescences of both N. gracillima and the closely related N. ramispina are very short, rarely exceeding 10 and 20 cm, respectively. Both female inflorescences of Ridley 16097 have a long peduncle and rachis, each exceeding 20 cm in length. In addition, the flowers of these species are almost always borne on pedicels, unlike those of Ridley 16097, which mostly have two-flowered partial peduncles.[14] Furthermore, the shape of the lamina is unlike that of N. gracillima or N. ramispina; despite being narrow and lanceolate, it is proportionately considerably longer and has a much narrower, almost sub-petiolate base. Kiew partly attributed the narrower leaf bases of Ridley 16097 to a preservation artefact, but Clarke stated that this explanation could not fully account for the differences. He also noted that the specimen exhibits a decurrent leaf attachment. Taking all of these morphological features into account, Clarke felt that Ridley 16097 most likely represented a specimen of N. benstonei.[12][15] At the time, he believed that Kiew had grouped both N. benstonei and N. ramispina with N. gracillima.[12] But in a 2012 revision of the Nepenthes of Mount Tahan, which included a reappraisal of the taxonomically confused N. alba and N. gracillima, Clarke and Ch'ien Lee concluded that Kiew's concept of N. gracillima had encompassed N. alba, N. benstonei, and N. gracillima.[2] Clarke and Lee also showed that Ridley 16097 represents a mixed collection and that only two of the three sheets belong to N. benstonei; the Kew specimen barcoded K000651564 is representative of N. alba.[2]

Other specimens

In addition to the two sheets of Ridley 16097, populations of N. benstonei from Mount Tahan are represented by the specimen Holttum 20643, held at the herbarium of the Singapore Botanic Gardens (SING).[2] A number of specimens collected from Terengganu also belong to N. benstonei. These are Shah et al. 3274, which is deposited at the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia in Kepong, and Shah et al. 3283, held at the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia near Kuala Lumpur.[12][16]

Specimens from peninsular Thailand originally assigned to N. benstonei in Cheek and Jebb's 2001 monograph, "Nepenthaceae",[8] have since been identified as belonging to a new species, N. thai.[9]

Description

Nepenthes benstonei is a climbing plant. The stem, which may be branched, can attain a length of 10 m[10] and is up to 0.6 cm in diameter. Internodes are cylindrical and up to 15 cm long.[12]

Leaves are coriaceous and sessile to sub-petiolate. The lamina is usually broadly linear-lanceolate in shape, but may also be slightly spathulate. Its base is a broad, amplexicaul sheath with decurrent margins. The lamina can reach 60 cm in length and 9 cm in width. It has a rounded to acute apex. The margins of the lamina usually meet the tendril unequally on both sides, being up to 3 mm apart. Three to five longitudinal veins are present on either side of the midrib. Pinnate veins are almost indistinct. Tendrils are up to 60 cm long.[12]

Rosette and lower pitchers reach 20 cm in height[16] and 5 cm in width. They are ovoid in the lower part and cylindrical above, with a pronounced hip in the middle. A pair of fringed wings (≤4 mm wide) runs the whole length of the pitcher cup. The pitcher mouth is round to ovate and oblique throughout. The peristome is up to 6 mm wide and bears very small but distinct teeth along its inner margin. The pitcher lid is ovate and lacks appendages. It bears a short but distinct keel and often has a very broad insertion. A simple or bifurcate spur (≤12 mm long) is inserted near the base of the lid.[12]

Upper pitchers are similar in most respects to their lower counterparts. They are up to 20 cm high[16] and 3 cm wide. They are infundibular in the lowermost part, narrowly ovoid in the next part, and cylindrical above. The peristome lacks teeth in upper pitchers. The lid is narrower and has a less obtuse apex. The spur is simple and much smaller, reaching only 5 mm in length.[12]

Nepenthes benstonei has a racemose inflorescence. The peduncle is up to 20 cm long and the rachis up to 30 cm long. The first flower is generally borne on a pedicel, sometimes with a simple, lanceolate bracteole (≤1.5 cm long). Subsequent flowers are produced on pedicels or two-flowered partial peduncles, which lack bracteoles. Sepals are ovate and around 4 mm long. Male inflorescences usually bear around twice as many flowers as female ones. N. benstonei is one of the few Nepenthes species known to produce multiple inflorescences concurrently on a single stem. Two to three are usually produced, originating from sequential nodes at the top of the stem. This unusual reproductive habit has also been observed, although much more rarely, in N. alba, N. ampullaria, N. attenboroughii, N. rigidifolia, N. sanguinea, and N. thai.[9][12][13] It is seen even more frequently in N. philippinensis.[13]

The stem and lamina have a sparse indumentum of simple white hairs. Short, branched reddish-brown hairs line the margins of the lamina. The outer surfaces of the pitchers bear a sparse covering of short, branched red hairs. The same hairs are more densely present on the margins of the lid and upper part of the pitcher directly below the peristome. Immature inflorescences have an indumentum of short white and red hairs throughout.[12]

The stem and leaves of N. benstonei bear a thick, waxy cuticle that often gives a whitish-blue sheen to the lamina and pitchers. Inflorescences are distinctly waxy throughout.[12]

No infraspecific taxa of N. benstonei have been described.[12]

Ecology

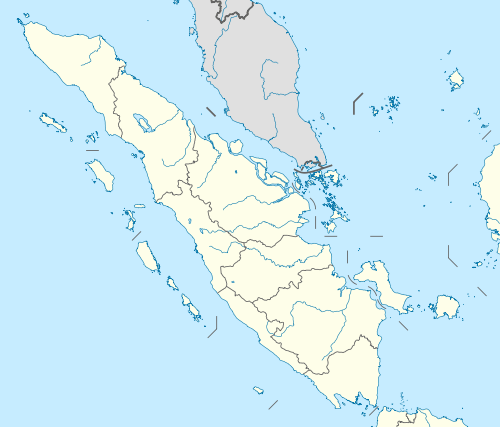

Nepenthes benstonei is endemic to Peninsular Malaysia. It is known with certainty only from the summits of low hills in Kelantan and northern Terengganu,[12][16] and from Mount Tahan in Taman Negara, Pahang.[2] The species has a relatively wide altitudinal range of 150[10] to 1350 m above sea level.[2]

Nepenthes benstonei grows terrestrially among open, secondary vegetation, where it is exposed to direct sunlight. It is very abundant near the summit of Bukit Bakar, where it grows on cuttings beside a paved road leading to a Telekom Malaysia station at the summit.[12][16] There, its altitudinal distribution appears to be restricted to 450–600 m.[12]

The species is also present on Mount Tahan, which at 2187 m is the highest mountain in Peninsular Malaysia. Its altitudinal range on Mount Tahan is known to extend from 800 to 1350 m. It is common on the mountain's lower slopes and can be seen along the western summit route from Sungai Relau, particularly on the tops of steep ridges at around 800–1200 m.[nb 1] It has been recorded growing along the western trail itself and from other disturbed sites, including areas affected by landslides. Plants have also been observed in dense forest, but these bear comparatively few pitchers. Though there were no confirmed reports of N. benstonei from Mount Tahan prior to 2012, the species's presence there is attested by much older herbarium material.[2]

Although the extent of its range is uncertain, N. benstonei appears to have a secure future in the wild as the type locality lies within a protected area and the species's unremarkable appearance means over-collection does not pose a serious threat.[12]

Related species

In his description of N. benstonei, Charles Clarke noted two characteristics that he considered unique among Nepenthes. These were the production of multiple inflorescences and the presence of a thick, waxy cuticle on the leaves.[1] Subsequent field studies have shown that the former is not unique to N. benstonei, but also occasionally occurs in other Nepenthes. Likewise, a number of other species, such as N. hirsuta from Borneo, are known to produce a waxy cuticle, although it is less developed than in N. benstonei.[12] Otherwise, N. benstonei lacks remarkable characteristics and is distinguished from related species on the basis of its stem, leaves, peristome, lid, indumentum, and glands of the digestive zone.[1]

Nepenthes benstonei appears to be related to N. sanguinea, which is also native to Peninsular Malaysia. It can be distinguished on the basis of its significantly larger leaves, which are often sub-petiolate and differ in shape. Nepenthes benstonei also has longer tendrils and a denser indumentum. The presence of teeth on the peristome of lower pitchers and of a thick, waxy cuticle on the leaves also serve to distinguish these taxa. In addition, herbarium specimens of N. benstonei tend to dry to a lighter colour than those of N. sanguinea.[12]

The pitchers of N. benstonei also resemble those of N. smilesii from Indochina. Clarke suggests that N. benstonei may represent an evolutionary link between the Nepenthes taxa of Indochina and Peninsular Malaysia.[16] Nepenthes benstonei also superficially resembles N. macrovulgaris from Borneo. It differs in producing multiple inflorescences, which are longer than those of N. macrovulgaris and bear one- or two-flowered partial peduncles, as opposed to exclusively two-flowered in the latter. The waxy coating of its leaves also separates these species.[12] Nepenthes benstonei has also been compared to N. albomarginata, although the presence of a white band below the peristome, which gives the latter its name, makes identification easy.[12] Upper pitchers of N. benstonei could be confused with those of N. mirabilis, although all other parts of the plant have little in common.[12]

In 2001, Charles Clarke performed a cladistic analysis of the Nepenthes species of Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia using 70 morphological characteristics of each taxon. The resultant cladogram placed N. benstonei in an unresolved polytomy at the base of the Montanae/Nobiles clade, together with N. rhombicaulis.[12]

Natural hybrids

Only one natural hybrid involving N. benstonei is known.[13] A single example of N. benstonei × N. mirabilis was discovered by Andrew Hurrell at the foot of Bukit Bakar, where the two species occur sympatrically.[12][16]

Notes

- The species was observed by Charles Clarke and Ch'ien Lee on 30 March 2011 at 4.6524°N 102.1875°E and adjacent areas, where it grew at 895 m altitude.[2]

References

- Clarke, C.M. 1999. Nepenthes benstonei (Nepenthaceae), a new pitcher plant from Peninsular Malaysia. Sandakania 13: 79–87.

- Clarke, C. & C.C. Lee 2012. A revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae) from Gunung Tahan, Peninsular Malaysia. Archived 2013-10-07 at the Wayback Machine Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 64(1): 33–49.

- Danser, B.H. 1928. 1. Nepenthes alata Blanco. [pp. 258–262] In: The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies. Bulletin du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg, Série III, 9(3–4): 249–438.

- Cheek, M. & M. Jebb 2013. Typification and redelimitation of Nepenthes alata with notes on the N. alata group, and N. negros sp. nov. from the Philippines. Nordic Journal of Botany 31(5): 616–622. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.2012.00099.x

- Schlauer, J. N.d. Nepenthes alata. Carnivorous Plant Database.

- Kiew, R.G. 1990. Pitcher plants of Gunung Tahan. Journal of Wildlife and National Parks (Malaysia) 10: 34–37.

- Jebb, M.H.P. & M.R. Cheek 1997. A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae). Blumea 42(1): 1–106.

- Cheek, M.R. & M.H.P. Jebb 2001. Nepenthaceae. Flora Malesiana 15: 1–157.

- Cheek, M.R. & M.H.P. Jebb 2009. Nepenthes group Montanae (Nepenthaceae) in Indo-China, with N. thai and N. bokor described as new. Kew Bulletin 64(2): 319–325. doi:10.1007/s12225-009-9117-3

- McPherson, S.R. & A. Robinson 2012. Field Guide to the Pitcher Plants of Peninsular Malaysia and Indochina. Redfern Natural History Productions, Poole.

- Schlauer, J. 2000. Literature reviews. Carnivorous Plant Newsletter 29(2): 53.

- Clarke, C.M. 2001. Nepenthes of Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- McPherson, S.R. 2009. Pitcher Plants of the Old World. 2 volumes. Redfern Natural History Productions, Poole.

- Shivas, R.G. 1984. Pitcher Plants of Peninsular Malaysia & Singapore. Maruzen Asia, Kuala Lumpur.

- Clarke, C.M. 2006. Introduction. In: Danser, B.H. The Nepenthaceae of the Netherlands Indies. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu. pp. 1–15.

- Clarke, C.M. 2002. A Guide to the Pitcher Plants of Peninsular Malaysia. Natural History Publications (Borneo), Kota Kinabalu.

- (in German) Meimberg, H. 2002. Molekular-systematische Untersuchungen an den Familien Nepenthaceae und Ancistrocladaceae sowie verwandter Taxa aus der Unterklasse Caryophyllidae s. l.. Ph.D. thesis, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Munich.

- Meimberg, H. & G. Heubl 2006. Introduction of a nuclear marker for phylogenetic analysis of Nepenthaceae. Plant Biology 8(6): 831–840. doi:10.1055/s-2006-924676

- Meimberg, H., S. Thalhammer, A. Brachmann & G. Heubl 2006. Comparative analysis of a translocated copy of the trnK intron in carnivorous family Nepenthaceae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 39(2): 478–490. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.023

- Thorogood, C. 2010. The Malaysian Nepenthes: Evolutionary and Taxonomic Perspectives. Nova Science Publishers, New York.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nepenthes benstonei. |

- Photographs of N. benstonei at the Carnivorous Plant Photofinder