Museums in Basel

The Basel museums encompass a series of museums in the city of Basel, Switzerland, and the neighboring region. They represent a broad spectrum of collections with a marked concentration in the fine arts and house numerous holdings of international significance. With at least three dozen institutions, not including the local history collections in the surrounding communities, the region offers an extraordinarily high density of museums compared to other metropolitan areas of similar size. They draw some one and a half million visitors annually.

Constituting an essential and defining component of Basel culture and cultural policy, the museums are the result of closely interwoven private and public collecting activities and promotion of arts and culture going back to the 16th century. The public museums of the canton of Basel-City arose from the 1661 purchase of the private Amerbach Cabinet by the city and the University of Basel and thus represent the oldest civic museum collection in continuous existence. Since the 1980s, a number of collections have been made public in new purpose-built structures that have achieved renown as acclaimed examples of avant-garde museum architecture.

Museum landscape

The main focus of collecting among Basel museums is the fine arts – painting, drawing and sculpture. More than a dozen museums cover a spectrum that extends from antiquity up to the present and includes historic and established works of art as well as pioneering creations. In particular, the latter category has been made increasingly accessible to the public over the past two decades in a series of newly opened museums. There are collections with more of a local and regional character, yet a number of area museums, especially the larger institutions, are noted for their international orientation and reach. In addition, Basel benefits from a long tradition of collecting that, in contrast to many other museums in Central Europe, was not disrupted by the wars of the 20th century, as well as from the city's well-established connections to the market of art dealers and art collectors – such as through Art Basel.

Kunstmuseum Basel; painting and drawing by Upper Rhine artists of the 14th to 16th centuries, art of the 19th and 20th centuries

Kunstmuseum Basel; painting and drawing by Upper Rhine artists of the 14th to 16th centuries, art of the 19th and 20th centuries Basel Museum of Ancient Art and Ludwig Collection; ancient art and culture from the Mediterranean region

Basel Museum of Ancient Art and Ludwig Collection; ancient art and culture from the Mediterranean region Museum of Contemporary Art and Media Art; [plug.in]; contemporary and avant-garde art from the 1960s up to the present

Museum of Contemporary Art and Media Art; [plug.in]; contemporary and avant-garde art from the 1960s up to the present Beyeler Foundation; classical modern art of the 20th century

Beyeler Foundation; classical modern art of the 20th century

Numerous museums address various themes of cultural history and ethnology while other institutions feature technical and scientific collections. The museums continue to be oriented to the scholarly tasks of collecting, conserving and exhibiting as well as research and education[1] or at least view these as part of their activities. Consistent with museological trends seen elsewhere, however, the traditional self-image has evolved since the 1960s. Alongside the new forms of public outreach (museum education and didactics), institutional hybrid forms have arisen that actively embrace a sociopolitically relevant role and in which museum operations constitute just one facet, albeit a highly important one, of a more comprehensive cultural institution.

Basel Museum of Cultures; European and non-European ethnology (Tibet, Bali, South Seas, Ancient America)

Basel Museum of Cultures; European and non-European ethnology (Tibet, Bali, South Seas, Ancient America) Swiss Paper Museum – Basel Paper Mill; paper production and the culture of writing

Swiss Paper Museum – Basel Paper Mill; paper production and the culture of writing Natural History Museum Basel; zoology, entomology, mineralogy, anthropology, osteology and paleontology

Natural History Museum Basel; zoology, entomology, mineralogy, anthropology, osteology and paleontology S AM Swiss Architecture Museum in Kunsthalle Basel; international architecture and contemporary urban design

S AM Swiss Architecture Museum in Kunsthalle Basel; international architecture and contemporary urban design

With the city's position at the junction of the "Dreiländereck" (Three-Countries Corner) and the compact municipal boundaries within the Basel region, most of Basel's museums are located in the city of Basel and thus in the canton of Basel-City but quite a few of museums lie in the canton of Basel-Country. The Basel museum landscape can also be said to extend to the museums of the greater metropolitan area, such as those in the neighboring towns of Lörrach, Saint-Louis and Weil am Rhein, with the latter included in the annual Basel Museum Night through the participation of Vitra Design Museum in Weil. In view of the numerous municipal, regional and national administrative units that come together here as well as the broader agglomeration,[2] it is difficult to produce a conclusive figure for the number of Basel museums. Yet even when taking a narrowly drawn perimeter, the total comes to at least three dozen institutions that house collections and make them accessible to the public. The Basel museums are also part of the German-French-Swiss "Upper Rhine Museum Pass" that was introduced in 1999. This covers a much wider area than the Basel region, however, extending via Strasbourg up to Mannheim.[3]

Museum am Burghof in Lörrach; history of the Three-Countries Region up to the present

Museum am Burghof in Lörrach; history of the Three-Countries Region up to the present- Toy Museum and Village and Wine Cultivation Museum in Riehen; toys, village life and wine growing

Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein; furniture design and architecture

Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein; furniture design and architecture Roman House in Augusta Raurica; finds from the Roman town and archaeological park

Roman House in Augusta Raurica; finds from the Roman town and archaeological park

With the increasing aestheticization of everyday life, the architecture of museums has taken on special significance since the 1980s. A striking number of exhibition structures have incorporated a vocabulary of postmodern and deconstructivist forms. In and around Basel, new buildings, additions or renovations have been constructed from designs by nationally and internationally renowned architects (Renzo Piano, Zaha Hadid, Frank O. Gehry, Wilfried and Katharina Steib, Herzog & de Meuron, Mario Botta) and celebrated as examples of avant-garde museum architecture. In other area museums, by contrast, the building fabric is old to very old, consisting of former residential and commercial buildings or monasteries and churches that have been converted for exhibition purposes.

Schaulager (architects: Herzog & de Meuron); Emmanuel Hoffmann Foundation

Schaulager (architects: Herzog & de Meuron); Emmanuel Hoffmann Foundation Tinguely Museum (architect: Mario Botta); Jean Tinguely and contemporaries

Tinguely Museum (architect: Mario Botta); Jean Tinguely and contemporaries Dollhouse Museum at Barfüsserplatz; dolls, teddy bears, miniatures

Dollhouse Museum at Barfüsserplatz; dolls, teddy bears, miniatures Historical Museum Basel – Barfüsser Church; cultural history of the city of Basel and the Upper Rhine

Historical Museum Basel – Barfüsser Church; cultural history of the city of Basel and the Upper Rhine

The museums are a central aspect of Basel's touristic appeal and hence an important economic factor. A number of Basel's museums are public institutions but the majority are privately sponsored, backed in most cases by foundations. Helping to generate the high density of museums compared to other cities and metropolitan areas of similar size,[4] these private collections have also made a substantial contribution to the high level of museum quality. The private collections nearly all came into being after the Second World War. Most of the public museums, by contrast, date from before the war. In fact, the collections of the five publicly run museums of the canton of Basel-City have histories that go back several centuries.

Development of the museums

Museums in the city

Early collections

The origins of the first public collection are closely linked to the University of Basel and the early modern era collections of books, art and natural curiosities, of which there were quite a few in Basel. Prominent among them, the Amerbach printer family (founded by Johann Amerbach) had collected a substantial number of books, paintings, goldsmith works, coins and natural objects during the 16th century. In 1661, the Amerbach Cabinet was on the verge of being disbanded following a purchase offer from Amsterdam, then the European center for the trade in collector's items. At the urging of the mayor Johann Rudolf Wettstein, the city and university decided to jointly purchase the collection in order to keep it in Basel. Installed in the Haus zur Mücke just off Cathedral Square in 1671, the collection did not operate like a museum. It principally served as a library for university scholars, with only a few parlors on the first floor reserved for works of art and natural objects. Two librarians were in charge of administering the overall collection.[5]

Beginning in the late 18th century, Basel saw an acceleration in the growth of collections of books and objects inspired by Enlightenment-era ideals of education and refinement. Significant holdings of antiquities, coins, fossils and natural curiosities made their way into the Haus zur Mücke through purchases, gifts or bequests by private collectors. An especially important addition came in 1823 with the contents of the Museum Faesch, a Basel collection from the 17th century. The first coherent ethnological collection was formed from the "Mexican cabinet" that had been assembled by the merchant Lukas Vischer from 1828 to 1837 during his travels in Central America. In 1821, the natural objects and artifacts were separated out from the collections in the Haus zur Mücke and an independent museum of natural history was established at the Falkensteiner Hof, likewise located right off Cathedral Square, which also included the instrument cabinets of the physics and chemistry institutes.[6]

The city's official repository for art was the Basel Town Hall (Rathaus) whose rich ornamentation and upkeep represented a constant undertaking for the city and a source of commissions for numerous artists from the early 16th century onward.[7] The city armory likely had a "museum corner" starting in the 16th century. Following common practice, weapons that had become unfit for war were decommissioned for disposal. In Basel, however, a substantial number of them were preserved, which means that the armory caretakers wished to store the obsolete medieval or early modern militaria for the sake of memory value. The most prominent examples were the real and supposed trophies of the Burgundian booty from 1476, which had fallen to Basel and remained on display to curious onlookers centuries later.[8] In contrast, the care and storage of the Basel Cathedral Treasury that had lost its liturgical value in the Reformation did not bear the character of a museum. Locked away in the cathedral sacristy for three centuries, the reliquaries and other religious objects remained inaccessible and out of view until 1833 and were merely listed as book value in the state budgets.

First museum building

In 1767, the university professor Johann Jakob d’Annone had the paintings and other objects moved to the previously empty ground floor of the Haus zur Mücke to create more space for the books on the first floor, and also provided for a more systematic organization. A few decades later, however, the building and its infrastructure no longer accommodated the increased volume of visitors (with the facility open four days of the week starting in 1829) and the modern culture of knowledge established through the Enlightenment. Moreover, a comprehensive index of the holdings was lacking, having been "altogether impossible heretofore in the inadequate premises where some pieces lay buried in darkened recesses for decades beneath an inch-thick layer of dust."[9]

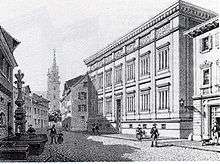

The need for space was resolved in 1849 with the removal of the collection to the multi-purpose building by Melchior Berri on Augustinergasse – simply named the "Museum" – on the site of the former Augustinian monastery. It was financed with a one-time contribution from the canton along with citizen donations. The late classicistic monumental edifice with decorative painting and frescoes by Arnold Böcklin is a comparatively early example of a civic museum and the first major museum in Basel. While taking clear inspiration from Karl Friedrich Schinkel and his Academy of Architecture in Berlin, the allocation of spaces and functions here combined university facilities with a library and natural history and art collections.[10] This also served the institutional requirements of the university. Further examples of collections could be found in most of the subsidiary institutes – i.e., facilities with demonstration objects for instruction and research purposes. These included the instruments of the chemistry and physics institutes and the utensils of the anatomical institute.

Division of the public collections into state museums

Parallel to the specialization of the educational and research disciplines that took hold at the beginning of the 19th century, Basel's wide-ranging holdings of objects evolved into institutional collections divided according to various scientific fields. They were very different from the cabinets of curiosities that, according to the Basel professor Wilhelm Wackernagel, had merely involved "[mindless grabbing] at curiosities with a half-pedantic, half-childish zeal".[11] The Natural History Museum (Naturhistorisches Museum) founded in 1821 was the first step in this new direction. In 1836, the art collection was made legally independent from the university library with a separate publicly funded art commission to oversee it. In 1856, the "medieval collection" took up residence in auxiliary rooms and annexes of the Basel Cathedral (Bishop's Court, St. Nicholas Chapel), having been established earlier that year with inventories from the Museum on Augustinergasse based on the model of the German National Museum in Nuremberg. In 1887, castings of ancient sculptures were put on display in the Sculpture Hall of the Basel Art Association (Basler Kunstverein). Meanwhile, in 1874, the chemistry and physics institutes had moved into the new Bernoullianum building for the study of the natural sciences, whereupon their holdings of objects shed their collection character in favor of laboratory facilities.[12][13] The canton had difficulty amassing funding and support for the creation of another museum for its collections. The Museum on Augustinergasse had represented a formidable beginning, yet remained the only one of its kind for nearly fifty years.

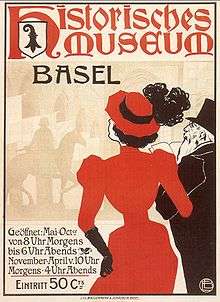

In 1892, the "antiquarian collection" (small artifacts of antiquity, excluding ethnological objects) was joined with the medieval collection of the Basel Cathedral and historical weapons from the Basel Armory to form the Historical Museum Basel (Historisches Museum Basel), with exhibition space in the reconverted Barfüsser Church from 1894 onwards. Today this museum houses the Upper Rhine's most comprehensive collection of cultural history, showing artisanal crafts (Cathedral Treasury, goldsmith works, stained glass) and objects of everyday culture (furnishings, tapestries, coin cabinet). Major emphasis is placed on the Late Middle Ages, Renaissance and Baroque periods. The entire inventory of books was incorporated into the collection of the new University Library in 1896. The "ethnographic collection", which was given the title Collection of Ethnology (Sammlung für Völkerkunde) in 1905, moved into new space created by an addition to the Museum on Augustinergasse in 1917, where it became the Museum of Ethnology (Museum für Völkerkunde). With holdings of approximately 300,000 objects and a comparable number of historical photographs, it is the largest ethnological museum in Switzerland and one of the largest in Europe. The collection includes objects from Europe, Ancient Egypt, Africa, Asia (Tibet and Bali Collections), Ancient America and Oceania. In 1944, the federal administration distinguished its European holdings as the Swiss Museum of Ethnology (Schweizerisches Museum für Volkskunde). However, since 1997 this division no longer exists; non-European and European collections are now joined in the Basel Museum of Cultures (Museum der Kulturen Basel), whose name intentionally expresses a change in emphasis from the presentation of “foreign” cultures to intercultural dialogue.[14] The Natural History Museum Basel (Naturhistorisches Museum Basel), which features most areas of the natural sciences (anthropology, mineralogy, paleontology, vertebrates, insects including the Frey Collection of Beetles and other invertebrates), has not only remained in its original location since 1849 but has also retained its traditional name. Its collections, comprising nearly eight million objects which are also dedicated to scientific research, bear the title "Archives of Life".

The public art collection was installed in the upper story of the Museum on Augustinergasse in 1849. Its continuing growth led to increasing spatial demands that could not be met at that location. In 1936, after a planning period of roughly three decades, the art collection moved into the Kunstmuseum Basel. Satellite locations had already been established in 1922 at the Augustinerhof on Augustinergasse (collection of prints and drawings) and at the Bachofenhaus on Cathedral Square (Bachofen Collection with additional holdings). The greater part of the art collection was temporarily housed in the Kunsthalle from 1928 until 1936.[15] The Kunstmuseum's gallery of paintings and collection of prints and drawings comprise the largest and most significant public art collection in Switzerland. With an emphasis on paintings and drawings by artists of the Upper Rhine from 1400 to 1600 (Holbein family, Witz, Cranach the Elder, Grünewald) and art of the 19th to 21st centuries (Böcklin, van Gogh, Cézanne, Gauguin, Cubism with Picasso and Braque, German Expressionism, postwar American art), it also ranks as one of the leading international museums of its kind. Since the removal of the art collection to new quarters, the Museum on Augustinergasse has served as the exclusive domain of the Natural History Museum and the Museum of Cultures/Museum of Ethnology (Völkerkundemuseum/Museum der Kulturen). A major expansion of the public museum collections occurred in 1961 with the founding of the Basel Museum of Ancient Art and Ludwig Collection (Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig). This new institution combined previous holdings from the Historical Museum (small artifacts of antiquity) and Kunstmuseum (sculptures) with acquisitions from private collections, which are displayed in two neoclassical villas located opposite the Kunstmuseum. The Museum of Ancient Art opened in the first villa in 1966 and expanded into the adjacent structure, also built by architect Melchior Berri, in 1988. It is the only Swiss museum devoted exclusively to the art of the Mediterranean area (mainly Egyptian, Etruscan, Greek, Italic and Roman cultures, as well as Levante and the Near East) from the 4th millennium B.C. to the 7th century A.D. The collections of Greek vases, Antique sculptures and Ancient Egyptian artifacts occupy a central position within its holdings.[16]

Satellite locations of the state museums

The growing spatial needs of the collections that were housed in the Museum on Augustinergasse led to the incorporation of neighboring buildings. Similarly, the other museums also expanded. The Historical Museum in Barfüsser Church acquired the following satellite locations: the Museum of Domestic Life (Wohnmuseum) in the Segerhof (1926–34) and its successor in the Haus zum Kirschgarten since 1951, the Museum of Domestic Culture in Basel (Museum der Basler Wohnkultur); the Museum of Music (Musikmuseum), featuring five centuries of European musical history based on the musical instrument collection founded in 1943, which has been displayed since 2000 in the former prison Lohnhof; the carriage and sleigh collection in Brüglingen, established in 1981.[17] Replica casts of ancient sculptures that were originally on display in the Sculpture Hall (Skulpturenhalle), but moved into storage in 1927 due to a lack of public interest, became part of the Museum of Ancient Art (Antikenmuseum) in 1961 and again received their own exhibition space in 1963 in the new Basel Sculpture Hall (Skulpturhalle Basel). It features the world's only complete reconstruction of architectural sculpture from the Parthenon in Athens.[18] The Public Art Collection (Öffentliche Kunstsammlung) also expanded into a second building in 1981 with the Museum of Contemporary Art (Museum für Gegenwartskunst) in St. Alban-Tal. As the first public exhibition building project in Europe, it is devoted exclusively to the presentation of contemporary works and artistic production since 1960. In addition to classic media such as painting and sculpture, its acquisitions also include video art.

Defunct and semi-public museums

The Museum of Applied Arts (Gewerbemuseum) was founded in 1878 by the Society of Trades and Craftsmen as a forum for the presentation of local arts and crafts. It became a semi-public institution in 1886 before coming under full public sponsorship in 1914. Renamed the Museum of Design (Museum für Gestaltung) in 1989 due to its broadening thematic spectrum, it was closed in 1996. Affected by the same cuts in public funding was the architecturally oriented City and Cathedral Museum (Stadt- und Münstermuseum), established in 1939 under the auspices of the public agency for the preservation of historic monuments in the former convent of Kleines Klingental. The holdings of the Museum of Design were distributed among other institutions, with the transferral of its library and poster collection to the School of Design (Schule für Gestaltung).[19] Thanks to the support of a foundation, the City and Cathedral Museum remains on the same premises under the present name Kleines Klingental Museum.

The Swiss Firefighting Museum (Schweizerisches Feuerwehrmuseum), founded in 1957 as the Basel Firefighting Museum, is housed on the premises of the cantonal Fire Brigade but does not have the status of a public museum and is not administered by the canton. Its collection, which includes permanent loans from the Historical Museum, features documents that date back to the 13th century.[20] The Hörnli Cemetery Collection (Sammlung Friedhof Hörnli) operates under similar conditions: It has been located on the property of the canton's Central Cemetery since 1994 but is funded and run by a private association. On display are burial objects such as urns, documents on the history of cremation, hearses, coffins, cemetery regulations, graveyard crosses, glass pearl chains and memorial keepsakes.

Additional museums

The first museum that was not supported and administered by the canton of Basel-City was established in 1860 in a large room at the Basel Mission. It presented ritual and cultural objects from the countries and ethnic groups among which the Basel Mission was active, as well as a portrait gallery of its missionaries. However, parts of this exhibit were later sold to the canton and the gallery space was closed.[21] The concept of a multi-purpose building, following the example of the Museum on Augustinergasse, was embraced by the Basel Art Society (Basler Kunstverein), which erected the Kunsthalle on Steinenberg between 1869 and 1872. In addition to exhibition space and administrative offices, this building housed a library and studio space for sculptors. A building wing added in 1885 accommodated the Sculpture Hall (Skulpturhalle), where the previously mentioned casts of Antique statues from the Museum on Augustinergasse were displayed from 1886 to 1927. The former Artists House (Künstlerhaus) now defines itself “as a hub between artists and art agents and as a place that brings together local and international developments.”[22] The next privately initiated museum was the above-mentioned Museum of Applied Arts (Gewerbemuseum); founded in 1878, it came under cantonal administration just eight years later.[23] The Anatomical Museum (Anatomisches Museum) of the University of Basel dates back to the acquisitional activities of Carl Gustav Jung in the 1820s. As the Collection of Pathology and Anatomy (Pathologisch-Anatomische Sammlung), it moved into its own building in 1880. Two especially significant objects in this collection are the oldest anatomical specimen in the world (prepared by Andreas Vesalius in Basel in 1543) and a skeleton prepared by Felix Platter in 1573.[24]

The Museum of Pharmacy (Pharmazie-Historisches Museum, originally the Historical Apothecary Collection) followed in 1924 after the donation of a private collection to the University of Basel. It is one of the world's largest collections on the history of pharmacy, encompassing old pharmaceuticals and early apothecary objects, laboratory utensils, ceramics, instruments, books, arts and crafts. The Swiss Gymnastics and Sports Museum (Schweizerische Turn- und Sportmuseum), established in 1945, was renamed as the Swiss Sport Museum in 1977. Sponsored by a foundation (Stiftung Sportmuseum Schweiz), its major focus is on ball sports, cycling, gymnastics and winter sports. The shipping museum Transport Hub Switzerland (Verkehrsdrehscheibe Schweiz) emerged from a 1954 exhibition by the Swiss Shipping Company (Schweizerische Reederei) in the Rhine ports of Basel, entitled “Our Path to the Sea.” It is also supported and run by an association of private citizens. The Swiss Historical Paper Collection (Schweizerische Papierhistorische Sammlung) was an affiliate of the Museum of Ethnology (Museum für Völkerkunde) from 1954 to 1979 before moving into independent quarters in the Gallician Mill, located in the former industrial district of St. Alban, in 1980. Now known as the Swiss Museum for Paper, Writing and Printing (Schweizerisches Museum für Papier, Schrift und Druck), it is sponsored by the Basel Paper Mill Foundation (Stiftung Basler Papiermühle). The Jewish Museum of Switzerland (Jüdisches Museum Schweiz), which presents the cultural history of Jews in Switzerland and in Basel including documents from the First Zionist Congress held in Basel in 1897, was founded by the Society for the Jewish Museum of Switzerland in 1966.[25]

Like the Kleines Klingental Museum, the Klingental Exhibition Gallery (Ausstellungsraum Klingental) is located in the building complex of the former Klingental convent. Opened in 1974, the gallery serves as a presentation platform for the current work of artists living in Basel and aims to support emerging artistic talents. It is sponsored by the Klingental Gallery Society (Verein Ausstellungsraum Klingental). The Caricature and Cartoon Museum Basel (Karikatur & Cartoon Museum Basel), by contrast, was initiated by an individual, the collector and patron Dieter Burckhardt. Founded in 1979, it is devoted to caricatures, cartoons, comics, parodies and pastiches. The eponymous foundation (Stiftung Karikatur & Cartoon Museum Basel) is a dependent affiliate of the Christoph Merian Foundation. The exhibition galleries have been located in a structure from the Late Gothic period since 1996, following the completion of renovations and a new building addition by the architects Herzog & de Meuron. The Swiss Architecture Museum (Schweizerisches Architekturmuseum), founded in 1984, has resided since 2004 in the building complex of the Kunsthalle, which was completely renovated and redesigned by the architectural offices Miller & Maranta and Peter Märkli.[26] The museum, sponsored by the Architecture Museum Foundation, presents alternating exhibitions on topics of international architecture and urbanism. An advantageous factor is the unusual concentration of internationally renowned architectural firms in Basel; Herzog & de Meuron, in particular, have made significant contributions to regional museum architecture.

Opened in 1996, the Tinguely Museum features a permanent exhibition on the life and work of the artist Jean Tinguely. The museum's temporary exhibitions present works by friends and contemporaries of Tinguely, as well as other modern artists. Designed by Mario Botta, the museum is financed entirely by the Basel pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-La Roche. The Dollhouse Museum (Puppenhausmuseum) was founded in 1998 by its patron and owner Gigi Oeri, who built up the collection herself. In addition to dolls, dollhouses and miniature shops from the 19th and 20th century, it displays the world's largest collection of teddy bears. The media art space [plug.in] opened its doors in 2000 with the backing of the Forum for New Media Association (Verein Forum für neue Medien), which had been founded the previous year. It realizes exhibitions and projects, provides artists with international networking opportunities and helps convey works of media art to the general public. With one of the world's most extensive collections of photographs (around 300,000 works with an emphasis on industrial society in the 19th century), the Herzog Foundation has exhibited its holdings since 2002 in a “Laboratory for Photography”. Located in the Dreispitz industrial sector, the warehouse converted by Herzog & de Meuron encompasses the collection along with a reference library on the history of photography and two additional rooms for study, teaching and research purposes.[27]

Museums in surrounding communities

Many of the small and mid-sized municipalities around Basel have museums of local history and culture[28] that are not presented in the following. Mention is given to institutions whose scope extends beyond the local level and which are generally open to the public several days a week.

Collections of natural, cultural and technological history

The oldest museum in the Basel region outside the city is the Museum of Canton Basel-Country (Museum des Kantons Basel-Landschaft) in Liestal, nowadays called Museum.BL. It was founded in 1837 as a "Cabinet of Natural Curiosities" (Naturaliencabinett) and up through the 1930s primarily took up objects of natural history into the collections. Since then, the emphasis has shifted toward cultural history. The diversity of the collection allows the museum to address wide-ranging themes related to the environment, history and the present day.[29] The Museum am Burghof in Lörrach traces its origins to the Lörrach Antiquities Association (Lörracher Altertumsverein) founded in 1882, which bequeathed its collection to the town of Lörrach in 1927. Commencing operations in 1932 as the Museum of Local History (Heimatmuseum), the current permanent exhibition “ExpoTriRhena” presents the history, present-day culture and divisions and similarities within the "Dreiländereck" (Three-Countries Corner) border region where Germany, France and Switzerland meet.[30]

Opened in 1957, the Roman Museum at Augst (Römermuseum Augst) is an open-air museum on the grounds of the former Roman city of Augusta Raurica, which has been the subject of excavations going back to the Renaissance. The exhibits feature numerous archaeological finds, including the largest silver treasure from Late Antiquity. The adjacent reconstruction of a Roman House (Römerhaus) was a gift of the Basel patron René Clavel while the museum and the entire archaeological park constitute a departmental division of Basel-Country. Located in the Brüglinger Plateau, the Mill Museum (Mühlemuseum) of the Christoph Merian Foundation is housed in the water mill of the former Brüglingen farming estate. The structure was converted into a museum in 1966 and presents the history of the mill and the work of millers from the Bronze Age up to the 20th century. The mill is still functional, allowing periodic demonstrations of the operational sequence from the water-powered mill wheel to the rotating millstone.

Opened to the public in 1972, the Toy Museum and Village and Wine Cultivation Museum (Spielzeugmuseum, Dorf- und Rebbaumuseum) in Riehen complements its exhibits of village history and wine growing with one of the most significant collections of European toys. The toys are drawn from private collections as well as loans from the Museum of Cultures (Museum der Kulturen). The museum is operated as a division of the municipal administration of Riehen.[31] The Museum of Music Automatons (Museum für Musikautomaten) in Seewen, located on the outermost periphery of the Basel museum territory, houses one of the world's largest and most well known collections of Swiss music boxes, disc music boxes, musical timepieces and jewelry and other mechanical musical automatons. It opened to the public in 1979 as a private museum of the collector Heinrich Weiss and was gifted to the Swiss Confederation in 1990. A newly remodeled and expanded facility for presentation of the exhibits was completed in 2000.[32] Finally, the Museum of Electricity (Elektrizitätsmuseum) of the electric utility Elektra Birseck opened its doors in Münchenstein in 1997. Exhibits explore the history and development of power production and its use. The collection contains rare historic equipment and is complemented by a laboratory in which visitors can experiment with electric power.

Emphasis on art collections

Since the late 1980s, the Basel region has seen a proliferation of new museums addressing themes of art and design, especially concerning works from more recent years. The Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein presents a broad range of design topics, with a special emphasis on furniture and interior design. Though originally based on the private collection of chairs and other furniture assembled by Rolf Fehlbaum, the owner of the Vitra furniture company, the museum was established as an independent institution. The Vitra building complex has made notable contributions to the body of avant-garde architecture in the Basel region. In addition to the 1989 museum by Frank O. Gehry, the grounds feature structures by Zaha Hadid, Nicholas Grimshaw, Tadao Ando and Álvaro Siza. In 1982, the Beyeler Foundation assumed ownership of the art collection of Hildy and Ernst Beyeler, which the couple had built up over half a century. Since 1997, the works of classical modern art have been exhibited in a building designed by Renzo Piano in the town of Riehen. Featured artists include Degas, Monet, Cézanne, van Gogh, Picasso, Rothko, Warhol, Lichtenstein and Bacon. The trees in the park surrounding the highly acclaimed building were wrapped by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in 1998.

With the creation of the Basel-Country Art Museum (Kunsthaus Baselland) in Muttenz, the Basel-Country Art Association (Kunstverein Baselland) was given its own dedicated exhibition building in 1997. The Art Museum is devoted to contemporary art and presents temporary exhibitions of current projects by regional and international artists.[33] Opened in 1998, Riehen Art Space (Kunst Raum Riehen) is another public institution with a similar thematic orientation. It serves the municipality of Riehen and its art commission with exhibitions of contemporary works of art from the region.[34] Established in 2001, the Sculpture at Schoenthal Foundation in the former Schönthal monastery presents over twenty works by international and Swiss artists in a permanently accessible sculpture park under the motto “Art and Nature in Dialogue”. A Romanesque-era church has been converted into a gallery for temporary exhibitions of contemporary artists.[35] In 2003, the Schaulager (or “viewing warehouse”) of the Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation was opened in Münchenstein. Centered on the avant-garde art collection of the foundation, the institute functions as a mix between public museum, art storage facility and art research institute. The polygonal building is a design by the architects Herzog & de Meuron. The Fernet Branca Contemporary Art Space (Espace d’Art Contemporain Fernet Branca) in Saint-Louis, the Alsatian town just across the border from Basel, is located in the former Fernet-Branca spirits distillery that was decommissioned in 2000. Since 2004, the museum has presented temporary exhibitions on contemporary art themes and artists. The museum's operations are supported by the Association for the Fernet Branca Contemporary Art Museum (Association pour le Musée d’Art Contemporain Fernet Branca).[36]

Museum promotion and museum policy

Primacy of the library

Many museums can be traced back to courtly collections – at least in terms of the original set of holdings. Since the 19th century, in contrast, Basel has embraced a culture of remembrance of having created the oldest existing civic museum collection through its purchase of the Amerbach Cabinet in the year 1661.[37] The acquisition of a collection from the 16th century fits with the historical and documentary interest in art that was prevalent at the time. In fact, however, the purchase was chiefly prompted by a desire to enhance the university's inventory of books with the extensive book holdings of the Amerbach Cabinet.[38] The Haus zur Mücke community hall that housed the university-administered collection was called the “Library” in recognition of its primary function. The role as the city's art repository did not shift from the Basel Town Hall (Rathaus) to the Haus zur Mücke until the latter half of the 18th century. The Passion Altarpiece by Holbein that had been one of the main visitor attractions since the Reformation was moved over in 1770, followed by several additional paintings from the town council's inventories in 1771 and Holbein's organ doors from the Cathedral in 1786.[39] Despite this weighting of the collections, the official legal status remained unchanged for quite some time. The natural history holdings and art collection were not split off from the library until 1821 and 1836, respectively.

At the end of the 18th century, civic museum culture was still in the early stages of its development, as illustrated by the very limited opening hours of the Haus zur Mücke (Thursday afternoon from two to four in the afternoon, otherwise on request[40]). The first records of regular gallery visits by city residents and outside visitors date to this period. In the three centuries before and after 1800, most of the collection activities involved objects of natural history, with a substantial number of acquisitions and gifts in this area. The numerous top-level art objects that made their way to Basel in the 1790s from Revolutionary France, on the other hand, did not find a wide audience of buyers and in most cases were resold.[41]

Transfer to the state and popular education

For the republican and monarchical civic states of the 19th century, collections in the form of public museums became emblems of self-determination. The carting off of large numbers of artworks to Paris during the Napoleonic Wars had created an awareness of the identity-shaping power of art. Institutional role models were the “Musée français” in the Louvre and the “Musée des monuments français” in a former Augustinian convent, which closed in 1816. The maintenance of programmatic museum collections and the construction of museum buildings became one of the most prominent and defining national functions.[42]

In the case of Basel, however, it was the increasing need for space in the Haus zur Mücke that prompted deliberations regarding construction of a new building. The discussion concerning the right location for the public collection took on a political dimension following the division of the canton into city and regional sections. The University Act (Universitätsgesetz) of 1818 had made the corporatively autonomous university a cantonal educational establishment, with the university holdings thus owned indirectly by the state. According to the arbitral decision governing the cantonal split, two-thirds of the university's collection belonged to the regional canton and had to be purchased by the city canton. The ensuing consternation in the city led to the Administration and Use of University Holdings Act (Gesetz über Verwaltung und Verwendung des Universitätsgutes) of 1836 that such goods were indissolubly tied to the locality of the city of Basel for the purposes of education. This provision has remained in effect to the present day.[43][44]

These occurrences led to the founding of the Voluntary Academic Society of Basel (Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft) in 1835, which began supporting the collections in financial terms and through purchases and gifts as part of its general promotion of the university. Yet the greatest momentum for the museum building came from natural science circles centered on the physics and chemistry professor Peter Merian, who was likely responsible for securing a dedicated annual budget for the Natural History Museum – the only state collection with this distinction. A combination of academic institution, library and laboratories, the establishment of the Natural History Museum at the Falkensteiner Hof also provided a model for the museum building. The fact that a primary museum building was ultimately created instead of a university-affiliated building was due to the university's poor standing among wide sections of the merchant and industrialist classes. In these sectors, the university was considered a backward-looking institution. The museum, by contrast, was seen as a driving force for practical popular education and the community was willing to support its construction with private contributions as part of a wider process of renewal in the city.[45][46]

At the instigation of Christian Friedrich Schönbein, the Voluntary Museum Association of Basel (Freiwilliger Museumsverein) was initiated in 1850 as the successor to an earlier association founded in 1841 for the construction of the museum. Modelled after the Royal Institution in London, it was established to “stimulate the appreciation of science and art”.[47] Open to all residents of Basel, the association promoted the collections with financial means and sought to generate interest in the museum through public lectures to which women were also admitted. It was unable to sustain the initial enthusiasm, however, and experienced losses in membership despite Basel's rapid population growth in the latter half of the century. The museum did not embrace the function of popular education that had been promoted by its founders and supporters. The ideational socialization role of the museum was very slow to proceed, with the museum long holding onto former organizational structures. The art collection furthermore did not get an academically trained conservator until 1887. In addition, the renewed University Act of 1866 discontinued regular state appropriations for the antiquarian, medieval and art collections and left them dependent on proceeds from entry fees and the support of associations and private individuals, the most significant of these being the Birrmann Foundation and the Emilie Linder Foundation on behalf of the art collection. It was this support that enabled an active collection policy that went beyond the receipt of inherited cultural assets.[48]

Civic culture of remembrance and modernism

From the outset, the museum authorities charged the collections with a federal mission, wanting them to exert a “beneficial and salutary influence on the entire Fatherland”.[49] The “unofficial national gallery”[50] grew over time, primarily through acquisitions of Swiss works of art. When negotiations got underway in 1883 regarding the establishment of a federal museum, the canton of Basel-City sought to be chosen as the location for the new institution and proposed its collections of cultural history as the nucleus of the museum, systematically expanding them in light of its candidacy. While the Swiss National Museum (Schweizerisches Landesmuseum) ended up in Zurich, plans were nevertheless realized for a history museum that was no longer generally Swiss but specifically related to Basel, located in the historic former Barfüsser Church from the High Gothic period. The establishment of the Historical Museum “was a self-assured display of Basel’s art-mindedness and craftsmanship, a mix of educational corridor and enfilade of stalls”.[51] The transfer of the Museum of Applied Arts (Gewerbemuseum) to the state a few years earlier as an arena of contemporary achievements can likewise be seen under the aspect of civic pride and reinvented sense of commonality in which the citizenry understood its ideals and capabilities as a foundation of state and society.

While the collections had clearly established their international standing, this appreciation did not become rooted in the cultural awareness of a broader range of social classes until the end of the 19th century. The historic culture of remembrance that was growing in importance and impact at the time was strongly linked with the medieval collection and the many Late Medieval and Renaissance works of the Upper Rhine in the Kunstmuseum. In the years since, Basel has also cultivated its claim of possessing the oldest municipal art collection in continuous existence through its acquisition of the Amerbach Cabinet.[52] On the occasion of two major public celebrations in 1892 (500th anniversary of Greater Basel's acquisition of Lesser Basel) and 1901 (Basel's 400th anniversary as part of the Swiss Confederation), Basel presented the civically minded portion of the population (and hence the base of support for the museums) with a series of identity-shaping historical and patriotic gestures that borrowed from the store of images from the past available in the museums.

[[File:Franz Marc-The Fate of the Animals-1913.jpg|thumb|Franz Marc: Animal Destinies, 1913. The painting was offered by the German Reich in 1939 as “degenerate art” and purchased by the city of Basel.]] With the epochal break of the First World War and in light of societal and cultural developments, the Basel museums became concerned with the citizenry's assertions of legitimacy and quest for recognition and their representation within these very same institutions. The discussions regarding the relationship of the museums to modernism took on particular relevance in the area of the fine arts. The construction of a dedicated museum for Basel's art collection ignited a “monumentality debate” in the late 1920s, in which the proponents of functionally oriented New Building (Neues Bauen) rejected the timelessly classic palatial form that was ultimately chosen as a demonstration of power by a conservative and “intellectually spent” notion of culture.[53] In contrast to the form of architectural expression and the general anti-modernistic spirit of the 1930s, the acquisitions from the 1920s up to the outbreak of the Second World War took a decisively modern tack. In 1934, the public art collection added its first painting by Vincent van Gogh along with an ensemble of 134 drawings by Paul Cézanne. Founded in 1933, the Emanuel Hoffmann Foundation supported the Kunstmuseum in these efforts and took up residence in the facility with its works of contemporary art in 1940. The breakthrough in altering the overall profile came with the special funding credit provided by the Basel-City parliament in 1939 at the instigation of museum director Georg Schmidt for the purchase of German museum holdings that the National Socialists had vilified as “degenerate art”.[54]

The establishment of classical modernism at the Kunstmuseum continued with ongoing acquisitions of postwar-era art, in particular with works by American artists. In Basel's claim to being a “Museum City”, the highly controversial and unsuccessful referendum against the purchase of two Picasso paintings in 1967 holds considerable importance and constitutes a key moment in Basel's culture of remembrance in regard to the fusing of society and museum.[56]

Democratization, popularization

Despite the affirmation by voters, traditional museums found themselves in a prolonged crisis beginning in the late 1960s. Not limited to Basel, this crisis originated in the profound sociopolitical reevaluation of culture of the era. The acquisitions of the State Art Credit and the 1967 Christmas exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel set off fierce protests among the loosely organized association of rejected artists, which became known as the Farnsburg Group (Farnsburgergruppe). Even the cantonal parliament got involved in addressing the concerns. The events raised the question of whether Basel was “just a museum city” – here meant in a derogatory sense – and prompted a broadly cast debate over the fostering of young artists and the functioning of the museums. The establishment of the Klingental Exhibition Gallery (Ausstellungsraum Klingental) several years later was a direct consequence of the shortcomings that had been identified.[57]

The democratization that took hold in the 1960s meant doing away with the elite in favor of the egalitarian, dispelling fears of the new and unknown. With a focus on the constructivist works of the 1960s associated with the “New Tendencies” (Nouvelles Tendances) movement, the short-lived Progressive Museum (1968–1974) set out to “establish a modern collection that would be accessible to the public from the very beginning” and wanted to avoid any sort of “secularized ceremony”.[58] The expansion of education and communication, likewise a mandate stemming from this era, could only be achieved through an increase in funding. Since the mid-1970s, however, increasingly tight budgets and persistent financial difficulties in the public sector have exerted a palpable impact on museums. The museum studies program at the University of Basel could only be offered from 1992 to 1994 due to funding shortages. In the mid-1990s, a government resolution cut the budget of the state museums by ten percent, leading to the 1996 closure of two museums, the Museum of Design (Museum für Gestaltung) and the City and Cathedral Museum (Stadt- und Münstermuseum).[59][60] The ensuing debate and the pressure from a public referendum in support of the city's museums led to the adoption of the Basel-City Museums Act (Museumsgesetz) of 1999, which placed the holdings of the remaining five state museums (Museum of Ancient Art, Historical Museum, Kunstmuseum, Museum of Cultures, Natural History Museum) in the hands of the parliament. As a central component of cultural expenditures,[61] the museums have also been included in the intensified negotiations over the past several years between the two Basel cantons regarding payment for the city-provided services within the framework of a fiscal equalization scheme.

Since the 1980s, the museums have experienced simultaneous trends toward popularization and aestheticization. The ensuing decades have been marked by a wave of new museum buildings whose avant-garde architecture has achieved international prominence. Contributing considerably to popularization was the exhibition concept of the Musée Sentimental, which focuses on the world of un-prosaic everyday culture and experience and led to a 1989 exhibition of the same name at the Museum of Design (Museum für Gestaltung). The annual Basel Museum Night tallies around a hundred thousand museum visits while the museums attract a total of approximately 1.4 million visitors throughout the year (as of 2006).[62] The general population credits the museums with “a leading role in providing leisure-time opportunities for education and learning”.[63] Museums operate in an environment that is increasingly subject to the conditions of both the leisure market and the free market, and are recognized as an important economic and locational factor.[64][65] In contrast to the state, the use of private funds in the museum field has grown considerably. Funding from patrons or sponsors plays an increasingly significant role in the financing of exhibitions, parts of collections or entire museums and is thus highly sought after. This competitive situation is further reflected in the considerable institutional autonomy of the Basel-City museums, which are the only governmental enterprises in the canton operating under the private-sector influenced method of New Public Management.[66]

Literature

- Birkner, Othmar; Rebsamen, Hanspeter (1986). INSA – Inventar der neueren Schweizer Architektur 1850–1920, Separatdruck Basel.

- Blome, Peter (1995). "Die Basler Museen und ihr Publikum." Basler Jahrbuch 1994, pp. 106–109.

- Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. 1460–1960. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel.

- Bruckner, A., ed. (1937). Basel. Stadt und Land. Ein aktueller Querschnitt. Benno Schwabe & Co Publishing, Basel, pp. 155–197.

- Historisches Museum Basel, pub. (1994). Historisches Museum Basel. Führer durch die Sammlungen. ISBN 1-85894-004-4.

- Huber, Dorothea (1993). Architekturführer Basel. Die Baugeschichte der Stadt und ihrer Umgebung. Architekturmuseum Basel, Basel. ISBN 3-905065-22-3.

- Kreis, Georg (1990). Entartete Kunst für Basel. Die Herausforderung von 1939. Wiese Publishing, Basel. ISBN 3-909158-31-5.

- Kreis, Georg; von Wartburg, Beat (2000). Basel. Geschichte einer städtischen Gesellschaft. Christoph Merian Publishing, Basel. ISBN 3-85616-127-9.

- Mathys, F. K. (1980). "Basels Schatzkammern. Zur Entstehung und Entwicklung unserer Museen." Basler Stadtbuch 1979, pp. 151–164.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde.

- Monteil, Annemarie (1977). Basler Museen. Birkhäuser Publishing, Basel. ISBN 3-7643-0945-8.

- Nagel, Anne; Möhle, Martin; Meles, Brigitte (2006). Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Basel-Stadt, Bd. VII Die Altstadt von Grossbasel I – Profanbauten. Berne.

- Öffentliche Kunstsammlung Basel (1936). Festschrift zur Eröffnung des Kunstmuseums. Birkhäuser Publishing, Basel.

- Schneider-Sliwa, R.; Erismann, C.; Klöpper, C. (2005). "Museumsbesuche – Impulsgeber für die Wirtschaft in Basel." Basler Stadt- und Regionalforschung, Volume 28. Basel.

- Settelen-Trees, Daniela (1994). Historisches Museum Basel in der Barfüsserkirche 1894–1994. Basel. ISBN 3-9520458-2-9.

- Suter, Raphael (1996). "Die Schliessung zweier Museen stösst auf Widerstand." Basler Stadtbuch 1995, pp. 158–161.

- Teuteberg, René (1986). Basler Geschichte. Christoph Merian Publishing, Basel. ISBN 3-85616-034-5.

- von Roda, Burkard (1995). "Was Basel reich macht." Basler Jahrbuch 1994, pp. 112–115.

- Wirtz, Rainer (1995). "Die neuen Museen – zwischen Konkurrenz und Kompensation." Basler Jahrbuch 1994, pp. 100–105.

References

- Especially in the case of the major cantonal museums in Basel-City: "The museums have the task of collecting, preserving, documenting, researching and communicating cultural assets." Museums Act (Museumsgesetz) from 16 June 1999, § 3.

- See the overview of different territorial definitions and perimeters on the website of Eurodistrict Basel Archived 2007-10-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Map Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine showing the area covered by the Upper Rhine Museum Pass.

- "Up until now, the label 'Museum City of Basel' was primarily associated with the valuable collections and numerous special exhibitions of the public and private museums that are present here in a unique density." (Suter, Raphael (1995): "Ist das erste Museologie-Studium der Schweiz bereits am Ende?" Basler Jahrbuch 1994, p. 109.) "Cities with a comparable number of inhabitants typically possess an art gallery of regional significance at best. As a location for art museums, measured in terms of its size, Basel is unmatched." (Becker, Maria (2 June 2008): "Die kleine Stadt der grossen Kunstschiffe". Neue Zürcher Zeitung.)

- Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel 1460–1960. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel, pp. 320–322.

- Mathys, F. K. (1980). "Basels Schatzkammern. Zur Entstehung und Entwicklung unserer Museen." Basler Stadtbuch 1979, pp. 151–164.

- Kreis, Georg; von Wartburg, Beat (2000). Basel. Geschichte einer städtischen Gesellschaft. Christoph Merian Publishing, Basel, pp. 395–396.

- Historisches Museum Basel (1994): Historisches Museum Basel. Führer durch die Sammlungen. Merrell Holberton, London, p. 87.

- Publication commemorating the dedication of the museum in Basel on 26 November 1849. Basel 1849, p. 3.

- Huber, Dorothea (1993). Architekturführer Basel. Die Baugeschichte der Stadt und ihrer Umgebung. Architekturmuseum Basel, Basel, pp. 112–114.

- Wackernagel, Wilhelm (1857): Über die mittelalterliche Sammlung zu Basel. Basel, p. 3.

- The Voluntary Museum Association of Basel (Freiwilliger Museumsverein) ended its support of the Bernoullianum in the 1870s, in contrast to the University Library, which remains a beneficiary of gifts and donations.

- Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel 1460–1960. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel, pp. 461–472.

- History of the Basel Museum of Cultures. Archived 2011-01-12 at the Wayback Machine

- History of the Kunstmuseum Basel.

- Departements of the Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig.

- Historisches Museum Basel (1994): Historisches Museum Basel. Führer durch die Sammlungen. Merrell Holberton, London, pp. 10–16.

- History of the Basel Sculpture Hall. Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- History of the Museum of Design (Museum für Gestaltung) Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine The museum was initially continued on a private basis in Weil am Rhein and then in Basel as an exhibition firm. The School of Design (Schule für Gestaltung) still mounts exhibitions with holdings from the poster collection.

- Mathys, F. K. (1980). "Basels Schatzkammern. Zur Entstehung und Entwicklung unserer Museen." Basler Stadtbuch 1979, p. 162.

- Mathys, F. K. (1980). "Basels Schatzkammern. Zur Entstehung und Entwicklung unserer Museen." Basler Stadtbuch 1979, p. 159.

- History of the Kunsthalle

- Mathys, F. K. (1980). "Basels Schatzkammern. Zur Entstehung und Entwicklung unserer Museen." Basler Stadtbuch 1979, pp. 159–160.

- Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel 1460–1960. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel, pp. 465–466.

- Mathys, F. K. (1980). "Basels Schatzkammern. Zur Entstehung und Entwicklung unserer Museen." Basler Stadtbuch 1979, pp. 160–163.

- Swiss Architecture Museum (Schweizerisches Architekturmuseum) The Architecture Museum opens its new premises in the Kunsthalle.

- Website of the Herzog Foundation.

- See the corresponding entries on the Basel-Country website: "Museums in the Municipalities" (in German)

- "History of the Museum.BL and its collections". Archived from the original on 2009-06-20. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- History of the Museum am Burghof. Archived 2009-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Monteil, Annemarie (1977). Basler Museen. Birkhäuser Publishing, Basel, p. 300.

- History of the Museum of Music Automatons.

- Informations about the Museum and the Art Association. Archived 2009-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Informations about the Riehen Art Space. Archived 2008-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Website of the Sculpture at Schoenthal Foundation

- Museum history Archived 2012-06-30 at Archive.today (French)

- There are older though no longer existent municipal collections. For instance, the Zurich Citizens’ Library (Zürcher Burgerbibliothek) was founded back in 1629 with an affiliated coin cabinet and art collection but closed its doors in 1780.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, p. 133.

- Kreis, Georg; von Wartburg, Beat (2000). Basel. Geschichte einer städtischen Gesellschaft. Christoph Merian Publishing, Basel, p. 397.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, p. 136.

- Kreis, Georg; von Wartburg, Beat (2000). Basel. Geschichte einer städtischen Gesellschaft. Christoph Merian Publishing, Basel, p. 398.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, pp. 121–122.

- The university holdings constitute “the indivisible property of the canton of Basel-City, indissolubly tied to the locality of the city of Basel and never to be alienated from the stipulations of the foundations and the function of the institutions of higher education.” University Holdings Act (Gesetz über das Universitätsgut) from 16 June 1999, § 2.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, pp. 124–125.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, pp. 130–131.

- Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. 1460–1960. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel, pp. 402–404.

- Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. 1460–1960. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel, p. 409.

- Bonjour, Edgar (1960). Die Universität Basel von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. 1460–1960. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel, pp. 467–470.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, p. 165.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, p. 179.

- Huber, Dorothea (1993). Architekturführer Basel. Die Baugeschichte der Stadt und ihrer Umgebung. Architecture Museum Basel, Basel, p. 193.

- Meier, Nikolaus (1999). Identität und Differenz. Zum 150. Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Museums an der Augustinergasse in Basel. Offprint from volume 100 of the Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde, pp. 122, 133.

- Huber, Dorothea (1993). Architekturführer Basel. Die Baugeschichte der Stadt und ihrer Umgebung. Architecture Museum Basel, Basel, pp. 301–302.

- Not obtained from private collections, none of the 21 acquired pieces had to be restituted after the war. Kreis, Georg (1997). Die Schweiz und der Handel mit Raubkunst im Zusammenhang mit dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Archived 2007-10-19 at the Wayback Machine

- The naming of the square followed a gift of four paintings by Pablo Picasso in appreciation of the positive referendum vote on the city’s purchase of two of his paintings.

- Monteil, Annemarie (1977). Basler Museen. Birkhäuser Publishing, Basel, pp. 13–14.

- "In 1967 – an exhibition of Basel's Farnsburg Group (Farnsburgergruppe) at the Klingental Exhibition Gallery (Ausstellungsraum Klingental)". Archived from the original on 2007-11-18. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- History of the Progressive Museum

- Suter, Raphael (1996). "Die Schliessung zweier Museen stösst auf Widerstand." Basler Stadtbuch 1995, pp. 158–161.

- Suter, Raphael (1996). "Ist das erste Museologie-Studium der Schweiz bereits am Ende?" Basler Stadtbuch 1995, pp. 109–111.

- The museums of Basel-City make up around a third of the canton’s annual culture budget of approximately a hundred million francs. See the 2009 Basel-City Culture Budget. Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Visitor figures of the museums in the canton of Basel-City According to the Statistical Office of Canton Basel-City, the Basel museums have the following visitor figures: 1,745,142 in 2004, 1,202,959 in 2005, 1,334,031 in 2006.

- Governing Council of Canton Basel-City: Politikplan 2008–2011, p. 9.

- Visitors figures of the museums in Basel-City. Attracting 600,000 visitors, the Tutankhamen exhibition at the Museum of Ancient Art boosted overnight hotel stays in Basel hotels by around 6% in 2004.

- Study by the Human Geography Institute (Humangeographisches Institut) of the University of Basel By conservative estimates, the Basel museums generate added value of at least 41 million francs per year (up to just under 55 million francs including the Museum am Burghof and the Vitra Design Museum).

- Museums Act (Museumsgesetz) from 16 June 1999, §§ 6, 9, 14.

External links

- Basel museums website on museums in and around Basel

- Museums in the Municipalities website (Museen in den Gemeinden – in German) on the museums of local history and culture in Basel-Country