Library of Pergamum

The Library of Pergamum in Pergamum, Turkey, was one of the most important libraries in the ancient world.[1]

The acropolis of Pergamum, seen from the Via Tecta at the entrance to the Asklepion | |

| Country | Pergamon |

|---|---|

| Type | National library |

| Established | 3rd century BC |

| Location | Pergamon |

| Map | |

| |

The city of Pergamum

Founded sometime during 8th century BC, prior to the Hellenistic Age, Pergamum or Pergamon was an important ancient Greek city, located in Anatolia. It is now the site of the modern Turkish town, Bergama. Ruled by the Attalid dynasty, the city rose to prominence as an administrative center under King Eumenes II of Pergamum, who formed an alliance with the Roman Republic, severing ties with Macedonia.

Under the rule of Eumenes II (197–160)[2] Pergamum was a wealthy, developing city with a population of over 200,000 people. Culturally it was rivaled only by the cities of Alexandria and Antioch. Many important works of sculpture and architecture were produced at this time, including the Great Altar of Pergamon. Upon the death of Attalus III, son of Eumenes II, in 133 BC, Pergamum was bequeathed to the Roman Republic. After the fall of Constantinople, Pergamum became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Pergamum was also an important city in the New Testament and was explicitly mentioned by St. John as one of the Seven Churches of Revelation in the Book of Revelation. The ruins of Pergamum and its library are now major archaeological sites in Turkey.

The Library of Pergamum

Pergamum was home to a library said to house approximately 200,000 volumes, according to the writings of Plutarch.[3] Built by Eumenes II between 220 and 159 BC and situated at the northern end of the Acropolis, it became one of the most important libraries in the ancient world. The cultured Pergamene rulers built up the library to be second only to the Great Library at Alexandria.[4] Flavia Melitene, who was a distinguished citizen of Pergamum and wife of a town councillor, was instrumental in supplying the library.[5] She also presented a statue of Hadrian to the library as a gift.[5] It is known that a certain Artemon was employed in the library during the second century B.C. though his personification is obscure.[6] No index or catalog of the holdings at Pergamum exists today, making it impossible to know the true size or scope of this collection.

The library consisted of four rooms, the largest of which was the main reading room (44.5 feet x 50 feet), lined with many shelves.[7] An empty space of approximately 50 centimetres (20 in) was left between the outer walls and the shelves to allow for air circulation, intending to prevent the library from becoming overly humid in the warm climate of Anatolia, an early attempt at library preservation.[7] A 3-meter (10 foot) statue of Athena, modeled after her statue in the Parthenon, stood in the main reading room.[7]

Manuscripts were written on parchment, rolled, and then stored on the shelves. In fact, the word "parchment" itself is derived from Pergamum (via the Latin pergamenum and the French parchemin). Pergamum was a thriving center of parchment production during the Hellenistic period.[8] The city so dominated the trade that a legend later arose indicating that parchment had been invented in Pergamon to replace the use of papyrus, which had become monopolized by the rival city of Alexandria. This however is a myth; parchment had been in use in Anatolia and elsewhere long before the rise of Pergamon.[9] Parchment reduced the Roman Empire's dependency on Egyptian papyrus and allowed for the increased dissemination of knowledge throughout Europe and Asia.

Competition

Although the library of Pergamum was built roughly a century after the library of Alexandria,[10] the two had a fierce rivalry, as libraries were often used to reflect wealth and culture. The two libraries competed for parchment, books, and even literary interpretation. Pergamum also hired some Homeric scholars, who studied the Iliad and the Odyssey. This resulted in a fierce rivalry in which each library tried to obtain copies of Homer's works, striving to have the most accurate and oldest works. They also tried to attract better scholars by offering competitive pay. Ultimately, this rivalry forced both libraries to innovate and improve.

Decline

The Kingdom of Pergamon fell to the Romans in 133 BC and the library grew neglected. According to a legend relayed by Plutarch, Mark Antony seized the collection of 200,000 rolls and presented them as a gift to his new wife Cleopatra in 43 BC,[7][11] presumably in an effort to restock the Library of Alexandria, which had been damaged during Julius Caesar's war in 48 BC.[3] Emperor Augustus returned some of the rolls to Pergamum after the death of Antony, and the library remained extant well into the Christian era,[11] though it was not mentioned much by later historians, indicating its collection was no longer significant.[3]

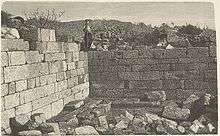

The ruins of the library sit on a hilltop near the Sanctuary of Athena and other buildings of the Pergamon Acropolis.

Notes

- Broggiato, Maria (2009). "Textual Criticism in Pergamum: Hermias on "Iliad" 16.207". Mnemosyne. 62 (4): 624–627. doi:10.1163/156852509X340002. JSTOR 27736381.

- 1914-2009., Casson, Lionel (2001). Libraries in the ancient world. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300097212. OCLC 232160789.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Richard Evans (2012). A History of Pergamum: Beyond Hellenistic Kingship. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781441162366.

- "Pergamum". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition, 1. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Pearcy, L. T. (1988). Galen's Pergamum. Archaeology, 38(6), 33-39.

- Broggiato, M. (2011). Artemon of Pergamum: A historian in context. Classical Quarterly, 61(2), 545-552.

- Clyde E. Fant & Mitchell G. Reddish (2003). A Guide to Biblical Sites in Greece and Turkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195139174.

- "parchment (writing material)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium. The historical evolution of the Hellenistic age, p. 168.

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-fierce-forgotten-library-wars-of-the-ancient-world

- Michael H. Harris (1999). History of Libraries of the Western World. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810877153.

References

- All About Archaeology, http://www.allaboutarchaeology.org/seven-churches-in-revelation.htm, accessed on April 16, 2007.

- All About Turkey, http://www.allaboutturkey.com/pergamum.htm, accessed on April 16, 2007.

- An Illustrated History of the Roman Empire, http://www.roman-empire.net, accessed on April 16, 2007.

- Cities of Revelation, http://www.luthersem.edu/ckoester/Revelation/Pergamum/Library.htm, accessed on April 16, 2007.

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online, http://www.britannica.com/eb/, accessed on April 16, 2007.

- Turkish Odyssey, https://web.archive.org/web/20070928072838/http://www.turkishodyssey.com/places/aegean/aegean1.htm, accessed on April 16, 2007.

- Kekeç, Tevhit. (1989). Pergamon. Istanbul, Turkey: Hitit Color. ISBN 9789757487012.