Mu Cephei

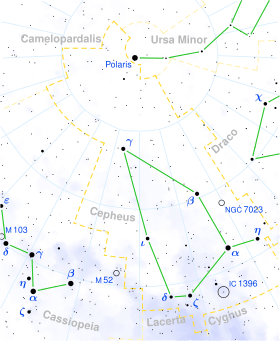

Mu Cephei (μ Cep, μ Cephei), also known as Herschel's Garnet Star, is a red supergiant or hypergiant[14] star in the constellation Cepheus. It appears garnet red and is located at the edge of the IC 1396 nebula. Since 1943, the spectrum of this star has served as the M2 Ia standard by which other stars are classified.[15]

| |

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Cepheus |

| Right ascension | 21h 43m 30.4609s[1] |

| Declination | +58° 46′ 48.166″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +4.08[2] (3.43 - 5.1[3]) |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | M2e Ia |

| U−B color index | +2.42[2] |

| B−V color index | +2.35[2] |

| Variable type | SRc[3] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +20.63[5] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 2.740±0.884[6] mas/yr Dec.: −5.941±0.922[6] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 0.4778 ± 0.4677[6] mas |

| Distance | 2,090+482 −469 ly (641+148 −144[7] pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −7.63[8] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 19.2±0.1[9] M☉ |

| Radius | 972±228[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 135,000+65,000 −64,000,[7] 269,000+111,000 −40,000[10] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | −0.36[11] cgs |

| Temperature | 3,551±136[7] (3,540[12]-3,789[13]) K |

| Age | 10.0 ± 0.1[9] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

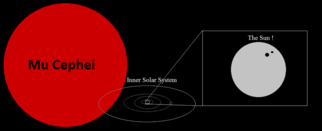

Mu Cephei is visually nearly 100,000 times brighter than the Sun, with an absolute visual magnitude of −7.6. It is also one of the largest known stars with a radius around 1,000 times that of the sun (R☉), and were it placed in the Sun's position it would engulf the orbit of Mars and possibly Jupiter.

History

.jpg)

The deep red color of Mu Cephei was noted by William Herschel, who described it as "a very fine deep garnet colour, such as the periodical star ο Ceti".[16] It is thus commonly known as Herschel's "Garnet Star".[17] Mu Cephei was called Garnet sidus by Giuseppe Piazzi in his catalogue.[18][19] An alternative name, Erakis, used in Antonín Bečvář's star catalogue, is probably due to confusion with Mu Draconis, which was previously called al-Rāqis [arˈraːqis] in Arabic.[20]

In 1848, English astronomer John Russell Hind discovered that Mu Cephei was variable. This variability was quickly confirmed by German astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander. Almost continual records of the star's variability have been maintained since 1881.[21]

The angular diameter of μ Cephei has been measured interferometrically. One of the most recent measurements gives a diameter of 18.672±0.435 mas at 800 μm, modelled as a limb-darkened disk 20.584±0.480 mas across.[22]

Variability

Mu Cephei is a variable star and the prototype of the obsolete class of the Mu Cephei variables. It is now considered to be a semiregular variable of type SRc. Its apparent brightness varies erratically between magnitude 3.4 and 5.1. Many different periods have been reported, but they are consistently near 860 days or 4,400 days.[23]

Properties

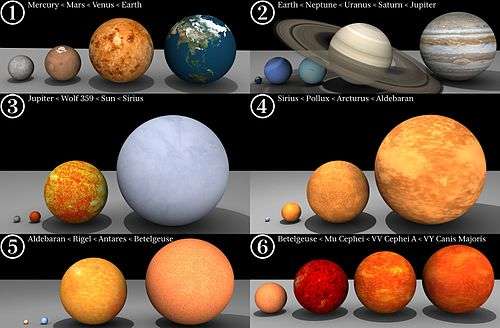

1. Mercury < Mars < Venus < Earth

2. Earth < Neptune < Uranus < Saturn < Jupiter

3. Jupiter < Wolf 359 < Sun < Sirius

4. Sirius < Pollux < Arcturus < Aldebaran

5. Aldebaran < Rigel < Antares < Betelgeuse

6. Betelgeuse < Mu Cephei < VV Cephei A < VY Canis Majoris.

A very luminous red supergiant, Mu Cephei is among the largest stars visible to the naked eye, and one of the largest known. It has been described as a hypergiant.[14]

This is a runaway star with a peculiar velocity of 80.7 ± 17.7 km/s.[9] The distance to Mu Cephei is not very well known. The Hipparcos satellite was used to measure a parallax of 0.55 ± 0.20 milliarcseconds, which corresponds to an estimated distance of 1,333–2,857 parsecs. However, this value is close to the margin of error. A determination of the distance based upon a size comparison with Betelgeuse gives an estimate of 390 ± 140 parsecs,[13] so it is clear that Mu Cephei is either a much larger star than Betelgeuse or much closer (and smaller and less luminous) than expected.[24]

The bolometric luminosity, summed over all wavelengths, is calculated from integrating the spectral energy distribution to be 283,000 L☉, making μ Cephei one of the most luminous red supergiants in the Milky Way. Its effective temperature of 3,750 K, determined from colour index relations, implies a radius of 1,260 R☉.[11] Other recent publications give similar effective temperatures. Calculation of the luminosity from a visual and infrared colour relation give 340,000 L☉ and a corresponding radius of 1,420 R☉.[8] An estimate made based on its angular diameter and an assumed distance of 2,400 light years gives it a radius of 1,650 R☉.[25]

More recent measurement based on a distance of 641+148

−144 pc gives the star a lower luminosity below 140,000 L☉ and a correspondingly lower radius of 972±228 R☉, and as well as a lower temperature of 3,551 K. These parameters are all consistent with those estimated for Betelgeuse.[7]

The initial mass of Mu Cephei has been estimated from its position relative to theoretical stellar evolutionary tracks to be between 15 M☉ and 25 M☉.[7][11]

Mu Cephei is surrounded by a shell extending out to a distance at least equal to 0.33 times the star's radius with a temperature of 2,055 ± 25 K. This outer shell appears to contain molecular gases such as CO, H2O, and SiO.[13]

Infrared observations suggest the presence of a wide ring of dust and water with an inner radius about twice that of the star itself, extending to about four times the radius of the star.[26]

The star is surrounded by a spherical shell of ejected material that extends outward to an angular distance of 6″ with an expansion velocity of 10 km s−1. This indicates an age of about 2,000–3,000 years for the shell. Closer to the star, this material shows a pronounced asymmetry, which may be shaped as a torus. The star currently has a mass loss rate of (4.9±1.0)×10−7 M☉ per year.[7]

Supernova

Mu Cephei is nearing death. It has begun to fuse helium into carbon, whereas a main sequence star fuses hydrogen into helium. When a supergiant star has converted elements in its core to iron, the core collapses to produce a supernova and the star is destroyed, leaving behind a vast gaseous cloud and a small, dense remnant. For a star as massive as Mu Cephei the remnant is likely to be a black hole. The most massive red supergiants will evolve back to blue supergiants, Luminous blue variables, or Wolf-Rayet stars before their cores collapse, and Mu Cephei appears to be massive enough for this to happen. A post-red supergiant will produce a type IIn or type II-b supernova, while a Wolf Rayet star will produce a type Ib or Ic supernova.[27]

Components

| NAME | Right ascension | Declination | Apparent magnitude (V) | Spectral type | Database references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ Cep B (CCDM J21435+5847B) | 21h 43m 27.8s | +58° 46′ 45″ | 12.3 | M0 | Simbad |

| μ Cep C (CCDM J21435+5847C) | 21h 43m 25.6s | +58° 47′ 08″ | 12.7 | A | Simbad |

References

- Perryman, M. A. C.; et al. (April 1997). "The HIPPARCOS Catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 323: L49–L52. Bibcode:1997A&A...323L..49P.

- Nicolet, B. (October 1978). "Catalogue of homogeneous data in the UBV photoelectric photometric system". Astronomy & Astrophysics Supplement Series. 34: 1–49. Bibcode:1978A&AS...34....1N.

- Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/GCVS. Originally Published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1: B/gcvs. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- Famaey, B.; et al. (2005). "Local kinematics of K and M giants from CORAVEL/Hipparcos/Tycho-2 data. Revisiting the concept of superclusters". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 430 (1): 165–186. arXiv:astro-ph/0409579. Bibcode:2005A&A...430..165F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041272.

- Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616. A1. arXiv:1804.09365. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Gaia DR2 record for this source at VizieR.

- Montargès, M.; Homan, W.; Keller, D.; Clementel, N.; Shetye, S.; Decin, L.; Harper, G. M.; Royer, P.; Winters, J. M.; Le Bertre, T.; Richards, A. M. S. (2019). "NOEMA maps the CO J = 2 − 1 environment of the red supergiant μ Cep". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 485 (2): 2417–2430. arXiv:1903.07129. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.485.2417M. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz397.

- Table 4 in Emily M. Levesque; Philip Massey; K. A. G. Olsen; Bertrand Plez; Eric Josselin; Andre Maeder & Georges Meynet (2005). "The Effective Temperature Scale of Galactic Red Supergiants: Cool, but Not As Cool As We Thought". The Astrophysical Journal. 628 (2): 973–985. arXiv:astro-ph/0504337. Bibcode:2005ApJ...628..973L. doi:10.1086/430901.

- Tetzlaff, N.; Neuhäuser, R.; Hohle, M. M. (January 2011), "A catalogue of young runaway Hipparcos stars within 3 kpc from the Sun", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 410 (1): 190–200, arXiv:1007.4883, Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410..190T, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17434.x.

- Davies, Ben; Beasor, Emma R. (March 2020). "The `red supergiant problem': the upper luminosity boundary of Type II supernova progenitors". MNRAS. 493 (1): 468–476. arXiv:2001.06020. Bibcode:2020MNRAS.493..468D. doi:10.1093/mnras/staa174.

- Josselin, E.; Plez, B. (2007). "Atmospheric dynamics and the mass loss process in red supergiant stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 469 (2): 671–680. arXiv:0705.0266. Bibcode:2007A&A...469..671J. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066353.

- Meneses-Goytia, S.; Peletier, R. F.; Trager, S. C.; Falcón-Barroso, J.; Koleva, M.; Vazdekis, A. (2015). "Single stellar populations in the near-infrared. I. Preparation of the IRTF spectral stellar library". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 582 (96): A96. arXiv:1506.07184. Bibcode:2015A&A...582A..96M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423837.

- Perrin, G.; et al. (2005). "Study of molecular layers in the atmosphere of the supergiant star μ Cep by interferometry in the K band". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 436 (1): 317–324. arXiv:astro-ph/0502415. Bibcode:2005A&A...436..317P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042313.

- Shenoy, Dinesh; Humphreys, Roberta M; Terry Jay Jones; Marengo, Massimo; Gehrz, Robert D; Andrew Helton, L; Hoffmann, William F; Skemer, Andrew J; Hinz, Philip M (2015). "Searching for Cool Dust in the Mid-to-Far Infrared: The Mass Loss Histories of the Hypergiants μ Cep, VY CMa, IRC+10420, and ρ Cas". The Astronomical Journal. 151 (3): 51. arXiv:1512.01529. Bibcode:2016AJ....151...51S. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/151/3/51.

- Garrison, R. F. (December 1993), "Anchor Points for the MK System of Spectral Classification", Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 25: 1319, Bibcode:1993AAS...183.1710G

- Herschel, W. (1783). "Stars newly come to be visible". Philosophical Transactions: 257.

- Allen, R. H. (1899). Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. G. E. Stechert. p. 158.

editions:CmkItwtawcMC.

- Piazzi, G., ed. (1803). Præcipuarum Stellarum Inerrantium Positiones Mediæ Ineunte Seculo XIX: ex Observationibus Habitis in Specula Panormitana ab anno 1792 ad annum 1802. Panormi.

- Piazzi, G., ed. (1814). Praecipuarum Stellarum Inerrantium Positiones Mediae Ineunte Saeculo XIX: ex Observationibus Habitis in Specula Panormitana ab anno 1792 ad annum 1813. Panormi. p. 159.

- Laffitte, R. (2005). Héritages arabes: Des noms arabes pour les étoiles (2éme revue et corrigée ed.). Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geunthner / Les Cahiers de l'Orient. p. 156, note 267.

- Brelstaff, T.; Lloyd, C.; Markham, T.; McAdam, D. (June 1997). "The periods of MU Cephei". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 107 (3): 135–140. Bibcode:1997JBAA..107..135B.

- Mozurkewich, D.; Armstrong, J. T.; Hindsley, R. B.; Quirrenbach, A.; Hummel, C. A.; Hutter, D. J.; Johnston, K. J.; Hajian, A. R.; Elias, Nicholas M.; Buscher, D. F.; Simon, R. S. (2003). "Angular Diameters of Stars from the Mark III Optical Interferometer". The Astronomical Journal. 126 (5): 2502. Bibcode:2003AJ....126.2502M. doi:10.1086/378596.

- Kiss, L. L.; Szabó, G. M.; Bedding, T. R. (2006). "Variability in red supergiant stars: Pulsations, long secondary periods and convection noise". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 372 (4): 1721–1734. arXiv:astro-ph/0608438. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.372.1721K. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10973.x.

- Tsuji, T. (2000). "Water on the Early M Supergiant Stars α Orionis and μ Cephei". The Astrophysical Journal. 538 (2): 801–807. Bibcode:2000ApJ...538..801T. doi:10.1086/309185.

- "Jim Kaler-Garnet star".

- Tsuji, Takashi (2000). "Water in Emission in the Infrared Space Observatory Spectrum of the Early M Supergiant Star μ Cephei". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 540 (2): 99–102. arXiv:astro-ph/0008058. Bibcode:2000ApJ...540L..99T. doi:10.1086/312879.

- Meynet, G.; Chomienne, V.; Ekström, S.; Georgy, C.; Granada, A.; Groh, J.; Maeder, A.; Eggenberger, P.; Levesque, E.; Massey, P. (2015). "Impact of mass-loss on the evolution and pre-supernova properties of red supergiants". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 575 (60): A60. arXiv:1410.8721. Bibcode:2015A&A...575A..60M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424671.

External links

- "mu. Cep". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- "GARNET STAR (Mu Cephei)". Jim Kaler: Stars. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- "Mu Cephei". AAVSO: Variable Star of the Season Archive. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- "IC 1396". Matt Ben Daniel: Starmatt Astrophotography. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- "Garnet Star". Jumk.de Webprojects: Big and Giant Stars. Retrieved 15 December 2013.