Mozabite people

The Mozabite people are a Berber ethnic group inhabiting the M'zab natural region in the northern Sahara in Algeria. They speak Mozabite (Tumẓabt), one of the Zenati languages in the Berber branch of the Afroasiatic family. Many also speak Maghrebi Arabic as a second language. Mozabites are primarily Ibadi Muslims, but there was a small population of Jews as well.[3]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Algeria | 150,000 Mozabite speakers (2007)[1] |

| Languages | |

| Mozabite (Tumẓabt), Maghrebi Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Ibadi) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Berbers[2] | |

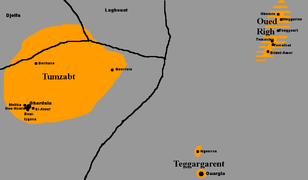

Mozabites mainly live in five oases; namely, Ghardaïa, Beni Isguen, El Atteuf, Melika and Bounoura, as well as two other isolated oases farther north: Berriane and Guerrara.

History

According to tradition the Ibadis, after their overthrow at Tiaret by the Fatimids during the 10th century, took refuge in the country to the south-west of Ouargla.[4] and founded an independent state there.[4]

In 1012, owing to further persecutions, they fled to their present location, where they long remained invulnerable.[4]

After the capture of Laghouat by France, the Mozabites concluded a convention with them in 1853, whereby they accepted to pay an annual contribution of 1,800 francs in return for their independence. In November 1882, the M'zab country was definitely annexed to French Algeria.[4]

Ghardaïa (population of 93,423) is the capital of the confederacy, followed in importance by Beni Isguen (4,916), the chief commercial centre.

Since the establishment of French control, Beni Isguen has become the depot for the sale of European goods.[4] The Mozabite engineers built a system of irrigation works that made the oases much more fertile than they used to be.[4]

Language

Mozabites speak Mozabite (Tumẓabt), a branch of the Zenati group of Berber languages.

Genetics

Mozabite people are characterized by a very high level of North African haplogroups E1b1b1b (M81) (86%) and U6 (28%).

Y-DNA

| Y-Dna | Nb | A/B | E(xE1b1b) | E1b1b1 (M35) | E1b1b1a (M78) | E1b1b1b (M81) | E1b1b1c (M123) | F | K | G | I | J1 | J2 | R1a | R1b | Other | Study |

| Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup | 67 | 0 | 4.5% | 0 | 1.5% | 86.6% | 1.5% | 0 | 0 | 1.5% | 0 | 1.5% | 0 | 0 | 3% | 0 | Dugoujon et al. (2009)[5] |

mtDNA

| mtDna | Nb | Eurasian lineages | Africa-centered lineages (L) | North African lineages (U6, M1) | Study |

| Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup | 85 | 54.1% | 12.9% | 33.0% | Coudray et al. (2009)[6] |

Mozabite Jews in French Algeria

It is not canonically agreed when Jews first came to Southern Algeria, but one theory suggests they were sent there by the Ibadite leadership in the 14th Century from Tunisia, as part of a merchant trade route. They continued as a merchant community, with subsequent waves of immigration during times of anti-Semitism across the Sahara, Europe, and the Middle East. In 1881, one year before the French annex of the Mzab, there were estimated 3,000 Mozabite Jews, out of 30,000 general Algerian Jews. By 1921, this number would grow to 74,000, a result of a spike in anti-Semitism in the later 1800s and early 1900s, though the Mozabite Jewish community would remain small, with most Jewish migrants settling in the North.[7]

In 1882, when the French military annexed the Mzab, they began an administrative rule that was separate from their Northern departments. Unlike their Northern Jewish counterparts, many of the Mozabite Berber Jews in Southern Algeria were classified by the French under the “indigenous code”. Given the diversity of the Mzab Jewish population, the French administration incorporated some “culturally Saharan”, but ethnically non-indigenous Jews into the North, and gave them citizenship under the Crémieux Decree of 1870. This perceived distinction by the French between Berber and non-Berber Jews of the Mzab was not a reflection of “technical precision”, but rather “a manufactured form of legal difference.”[8] While the French sought to assimilate the Northern Jewry as French citizens, they recognized religious rule of the Mozabite Jewish population, while keeping them separate under indigenous law, which meant severely limited political and social power.[9]

With anti-Semitism on the rise in the late 1800s, French colonial powers sought to decrease Jewish commerce in the South, and prevent further Jewish collaboration with Muslim communities. They continued to distance the Mozabite Jews from other Algerian Jewish affairs, keeping Mozabite, or “Mosaic” laws for civil matters, and French indigenous laws for public and criminal matters. It was not until 1961, with the French National Assembly Law 61-805 that the Mozabite Jews were granted “common law civil status” and French citizenship.[10]

See also

References

- Tumzabt - Ethnologue (17th ed., 2013)

- http://www.tlfq.ulaval.ca/AXL/monde/famarabe.htm

- Behar, Doron M., et al. "The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people." Nature 466.7303 (2010): 238.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 145.

- Dugoujon J.M., Coudray C., Torroni A., Cruciani F., Scozzari F., Moral P., Louali N., Kossmann M. The Berber and the Berbers: Genetic and linguistic diversities. In: Become Eloquent. Edited by J.M. Hombert and F. d’Errico. Ed. John Benjamins. pp 123-146; 2009

- "The complex and diversified mitochondrial gene pool of Berber populations". Ann. Hum. Genet. 73: 196–214. March 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2008.00493.x. PMID 19053990.

- Campbell, C. L., Palamara, P. F., Dubrovsky, M., Botigue, L. R., Fellous, M., Atzmon, G., Oddoux, C., Pearlman, A., Hao, L., Henn, B. M., Burns, E., Bustamante, C. D., Comas, D., Friedman, E., Pe'er, I. and Ostrer, H. Campbell, C. L. et al. "North African Jewish And Non-Jewish Populations Form Distinctive, Orthogonal Clusters." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109.34 (2012): 13865-13870. Web. 7 Apr. 2018.

- Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. Jews, trans-saharan commerce, and Southern Algeria under french colonial rule. University of Nebraska Press. January 2016.

- Shepard, Todd. The invention of decolonization: the Algerian War and the remaking of France. Cornell University Press, 2008.

- Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. Saharan Jews and the fate of French Algeria. University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- A. Coyne, Le Mzab (Algiers, 1879); Rinn, Occupation du Mzab (Algiers, 1885)

- Amat, Le M'Zab el les M'Zabites (Paris, 1888)