Monty Python's The Meaning of Life

Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, also known simply as The Meaning of Life, is a 1983 British musical sketch comedy film written and performed by the Monty Python troupe, directed by Terry Jones. It was the last film to feature all six Python members before Graham Chapman died in 1989.

| Monty Python's The Meaning of Life | |

|---|---|

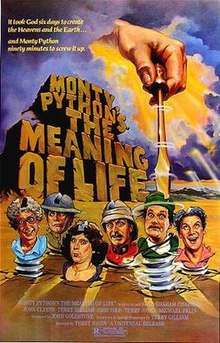

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Terry Jones |

| Produced by | John Goldstone |

| Written by | |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Du Prez |

| Cinematography | Peter Hannan |

| Edited by | Julian Doyle |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $9 million[2] |

| Box office | $14.9 million[3] |

Unlike Holy Grail and Life of Brian, the film's two predecessors, which each told a single, more-or-less coherent story,[2] The Meaning of Life returned to the sketch format of the troupe's original television series and their first film from twelve years earlier, And Now for Something Completely Different, loosely structured as a series of comic sketches about the various stages of life. It was accompanied by the short film The Crimson Permanent Assurance.

Released on 23 June 1983 in the United Kingdom,[4] The Meaning of Life, although not as acclaimed as its predecessors, was still well received critically and was a minor box office success, grossing almost $15 million on a $9 million budget. It also screened at the 1983 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Grand Prix. The film appears in a 2010 list of the top 20 cult films published by The Boston Globe.[5]

Plot

A group of fish in a posh restaurant's tank swim together casually, until they look at the customers outside of the tank and see their friend Howard being eaten. This leads them to question the meaning of life. The question is explored in the first sketch, "The Miracle of Birth", which features a woman in labour being ignored by the doctors in favour of impressing the hospital's medically-clueless administrator. Meanwhile, in Yorkshire, described as "the third world", a Roman Catholic man loses his job and returns home to tell his numerous children that he will have to sell them off for scientific experiments due to the Catholic church's opposition to contraception; this leads to the musical number "Every Sperm Is Sacred". A Protestant man with his wife looks on disapprovingly, and proudly remarks that Protestants can use contraception and have sex for pleasure (though his wife points out that they never do).

In "Growth and Learning", a class of boys are taught school etiquette before partaking in a sex education lesson, which involves watching their teacher have sex with his wife. One boy laughs, and is forced into a violent rugby match pitting pupils against the adult school masters as punishment. "Fighting Each Other" focuses on three scenes concerning the British military: first a World War I officer tries to rally his men during an attack, but they insist on presenting him with various going-away presents, including a card, a cake, and a clock; second, a modern army RSM attempts to drill his platoon, but his sarcastic remarks asking what they'd "rather be doing" ends with him actually dismissing them all to pursue leisure activities. Lastly, in 1879, during the Anglo-Zulu War, a soldier finds his leg has been bitten off. Suspecting a tiger (despite being non-native to Africa) the soldiers hunt for it and find two men suspiciously wearing two halves of a tiger costume.

The prior sequences ends abruptly with a host introducing "The Middle of the Film", beginning with a surreal segment called "Find the Fish", wherein bizarre characters ask the audience to find a hidden fish over a strange musical number. "Middle Age" involves a middle-aged American couple visiting a Hawaiian restaurant themed around Medieval torture, where, to the interest of the fish, the waiter offers a conversation about philosophy and the meaning of life. The customers are unable to make sense of it and move on to a discussion of "live organ transplants". "Live Organ Transplants" involves two paramedics visiting Mr. Brown, a card-carrying organ donor, forcefully removing his liver while he is still alive. Mrs. Brown is initially reluctant to donate her own liver while alive, but she relents after a man steps out of a fridge and sings the "Galaxy Song", discussing man's insignificance in comparison to the enormousness of the universe. The Crimson Permanent Assurance pirates from the short pre-film feature appear to invade a corporate boardroom where executives are discussing the meaning of life, but a tumbling skyscraper ends their assault.

"The Autumn Years" starts off with a musician in a French restaurant singing about the joys of having a penis. When the song is finished, the horrible, gluttonous, and grotesquely obese Mr. Creosote visits the restaurant, much to the horror of the other guests and the fish tank. He vomits continuously and devours an enormous meal. When the maître d' persuades him to eat one last wafer-thin mint, Creosote's stomach begins to rapidly expand until it explodes, spewing his chewed-up food on various diners, and the maître d' gives him the bill. Two staff members clean up Creosote's remains while discussing the meaning of life. A third waiter leads the audience to his house, spouts some weak philosophy, and then angrily dismisses them after his point trails off.

"Death" features a condemned man choosing the manner of his own execution: being chased off the Cliffs of Dover by topless women in sports gear and falling into his own grave below. In a short animated sequence, several despondent leaves commit suicide by throwing themselves from the branches of their tree. The Grim Reaper thereupon enters an isolated country house, where the hosts and dinner guests are all clueless as to who he is until the Reaper reveals his identity and tells them they all died of food poisoning from eating spoiled salmon (although one guest points out she didn't even eat it). They accompany the Grim Reaper to Heaven, revealed to be the Hawaiian restaurant from earlier. They enter into a Las Vegas-style hotel where it's always Christmas, with all the characters from the previous sketches as guests, and where a Tony Bennett-style singer performs "Christmas in Heaven" to the cast.

The song is cut off abruptly for "The End of the Film." An epilogue features the host of "The Middle of the Film" being handed an envelope containing the meaning of life. Pronouncing it "nothing very special," she blandly reads it out: "Try and be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try and live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations".

Cast

- Graham Chapman as Chairman / Fish No. 1 / Doctor / Harry Blackitt / Wymer / Hordern / General / Coles / Narrator No. 2 / Dr Livingstone / Transvestite / Eric / Guest No. 1 / Arthur Jarrett / Geoffrey / Tony Bennett-esque singer

- John Cleese as Fish No. 2 / Dr Spencer / Humphrey Williams / Sturridge / Ainsworth / Waiter / Eric's assistant / Maître D' / Grim Reaper

- Terry Gilliam as Window Washer / Fish No. 4 / Walters / Middle of the Film announcer / M'Lady Joeline / Mr Brown / Howard Katzenberg

- Eric Idle as Gunther / Fish No. 3 / 'Meaning of Life' singer / Mr Moore / Mrs Blackitt / Watson / Blackitt / Atkinson / Perkins / Victim #3 / Man in Front / Mrs Hendy / Man in Pink / Noël Coward / Gaston / Angela

- Terry Jones as Bert / Fish No. 6 / Mum / Priest / Biggs / Sergeant / Man with Bendy Arms / Mrs. Brown / Mr Creosote / Maria / Leaf Father / Fiona Portland-Smythe

- Michael Palin as Window Washer / Harry / Fish No. 5 / Mr Pycroft / Dad / Narrator No. 1 / Chaplain / Carter / Spadger / Regimental Seargeant Major / Pakenham-Walsh / Man in Rear End / Female TV Presenter / Mr Marvin Hendy / Governor / Leaf Son / Debbie Katzenberg

The main company of Monty Python members, who appeared in multiple roles in nearly every section of the film, was supported by featured cast mates:

- Carol Cleveland

- Simon Jones

- Patricia Quinn

- Judy Loe

- Andrew Bicknell

- Mark Holmes

- Valerie Whittington

- Matt Frewer

- John Scott Martin

Production

According to Palin, "the writing process was quite cumbersome. An awful lot of material didn't get used. Holy Grail had a structure, a loose one: the search for the grail. Same with Life of Brian. With this, it wasn't so clear. In the end, we just said: 'Well, what the heck. We have got lots of good material, let's give it the loosest structure, which will be the meaning of life'".[2]

After the film's title was chosen, Douglas Adams called Jones to tell him he had just finished a new book, to be called The Meaning of Liff; Jones was initially concerned about the similarity in titles, which led to the scene in the title sequence of a tombstone which, when hit by a flash of lightning, changes from "The Meaning of Liff" to "The Meaning of Life".[2]

.jpg)

Principal photography began on 12 July 1982 and was completed about two months later, on 11 September. A wide variety of locations were used, such as Porchester Hall in Queensway for the Mr Creosote sketch, where hundreds of pounds of fake vomit had to be cleaned up on the last day due to a wedding being scheduled hours later. The Malham Moors were chosen for the Grim Reaper segment; the countryside near Strathblane was used for the Zulu War; and "Every Sperm Is Sacred" was shot in Colne, Lancashire with interiors done at Elstree Studios.[6]

The film was produced on a budget of less than US$10 million, which was still bigger than that of the earlier films. This allowed for large-scale choreography and crowd sequences, a more lavishly produced soundtrack that included new original songs, and much more time able to be spent on each sketch, especially The Crimson Permanent Assurance. Palin later said that the larger budget, and not making the film for the BBC (i.e., television), allowed the film to be more daring and dark.[2]

The idea for the hospital sketch came from Chapman, himself a doctor,[7] who had noticed that hospitals were changing, with "lots and lots of machinery".[2] According to Palin, the organ transplant scene harked back to Python's love of bureaucracy, and sketches with lots of people coming round from the council with different bits of paper.[2]

During the filming of the scene where Palin's character explains Catholicism to his children, his line was "that rubber thing at the end of my sock", which was later overdubbed with cock.[2]

The Crimson Permanent Assurance

The short film The Crimson Permanent Assurance introduces the feature. It is about a group of elderly office clerks working in a small accounting firm. They rebel against yuppie corporate masters, transform their office building into a pirate ship, and raid a large financial district. One of the boardrooms raided reappears later in the film, from shortly before the attack begins until the narrator apologises and a skyscraper falls and crushes the marauders.

The short was intended as an animated sequence in the feature,[8] for placement at the end of Part V.[9] Gilliam convinced the other members of Monty Python to allow him to produce and direct it as a live action piece instead.

Release

The original tagline read "It took God six days to create the Heavens and the Earth, and Monty Python just 90 minutes to screw it up"[10] (the length of The Meaning of Life proper is 90 minutes, but becomes 107 minutes as released with the "Short Subject Presentation", The Crimson Permanent Assurance). In an April 2012 re-release held by the American Film Institute, the tagline is altered to read "It took God six days to create the Heavens and the Earth, and Monty Python just 1 hour and 48 minutes to screw it up".[11]

Ireland banned the film on its original release as it had previously done with Monty Python's Life of Brian, but later rated it 15 when it was released on video. In the United Kingdom the film was rated 18 when released in the cinema[1] and on its first release on video, but was re-rated 15 in 2000. In the United States the film is rated R.[12]

Reception

Box office

The film opened in North America on 31 March 1983. At 257 cinemas it ranked number six at the US box office, grossing US$1,987,853 ($7,734 per screen) in its opening weekend. It played at 554 cinemas at its widest point, and its total North American gross was $14,929,552.[3]

Critical reception

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film two and a half stars out of four, calling it a "a barbed, uncompromising attack on generally observed community standards".[13] In The New York Times, Vincent Canby declared it "the Ben Hur of sketch films, which is to say that it's a tiny bit out of proportion", concluding it was amusing, but he wished it were consistently amusing.[12] Variety staff assessed it as disgusting, ridiculous, tactless, but above all, amusing.[14] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune awarded 3 stars out of 4, calling it "fresh and original and delightfully offensive. What more can you ask of a comedy?"[15] Sheila Benson of the Los Angeles Times wrote that the film was full of "raunchy talk, blasphemy (well, sacrilege) and one example of what kids call a totally gnarly, gross-out scene. The problem for the reviewer (to be specific, this reviewer) is when you are laughing this much it makes logging all the fast-flying offenses almost impossible."[16] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post was negative, writing that "The strongest impressions left by this picture have less to do with its largely tedious attempts to burlesque human weakness and pomposity than with the group's failure to evolve a coherent satiric outlook."[17] A review by Steve Jenkins in The Monthly Film Bulletin was also negative, writing that the return to a sketch format constituted a "great leap backwards" for the troupe and that the film's outrageous moments "cannot disguise the overall air of déjà vu and playing it safe."[18]

In 2007, Empire's Ian Nathan rated it three of five stars, describing it as "too piecemeal and unfocused, but it possesses some of their most iconic musings and inspired madness".[19] In 2014, The Daily Telegraph gave the film four stars out of five.[20] In his 2015 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin awarded it three stars, calling it "A barrel of bellylaughs", identifying the Mr. Creosote and "Every Sperm Is Sacred" sketches as the most memorable.[21] Family Guy creator Seth MacFarlane states: “I view Monty Python as the great originator of that combination [provocative humour and high-quality original music]. The Meaning of Life in particular comes to mind, and my favorite example is "Every Sperm Is Sacred." It's so beautifully written, it's musically and lyrically legit, the orchestrations are fantastic, the choreography and the presentation are very, very complex – it's treated seriously."[22] The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 86%, based on 35 reviews, with an average rating of 7.3/10.[23]

Accolades

The Meaning of Life was awarded the Grand Jury Prize at the 1983 Cannes Film Festival.[24] While the Cannes jury, led by William Styron, were fiercely split on their opinions on several films in competition, The Meaning of Life had general support, securing it the second-highest honour after the Palme d'Or for The Ballad of Narayama.[25]

At the 37th British Academy Film Awards, Andre Jacquemin, Dave Howman, Michael Palin and Terry Jones were also nominated for Original Song for "Every Sperm is Sacred." The award went to "Up Where We Belong" in An Officer and a Gentleman.[26]

Home media

A two-disc DVD release in 2003 features a documentary on production and a director's cut,[27] which adds deleted scenes into the film, making it 116 minutes. The first is The Adventures of Martin Luther,[28] inserted after the scene with the Protestant couple talking about condoms. The second is a promotional video about the British army, which comes between the marching around the square scene and the Zulu army scene. The third and last is an extension of the American characters performed by Idle and Palin; they are shown their room and talk about tampons. In Region 1, it was released on Blu-ray to mark its 30th anniversary.[29] In May 2020, it was released on Netflix in the United Kingdom.

References

- "MONTY PYTHON'S THE MEANING OF LIFE (18)". United International Pictures. British Board of Film Classification. 26 April 1983. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- Michael, Chris (30 September 2013). "How we made Monty Python's The Meaning of Life". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- "Monty Python's The Meaning of Life". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- McCall, Douglas (2013-11-12). Monty Python: A Chronology, 1969-2012, 2d ed. p97. McFarland. ISBN 9780786478118.

- Boston.com Staff (27 December 2010). "Top 20 cult films, according to our readers". boston.com. The Boston Globe. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Douglas, McCall (2013). Monty Python: A Chronology, 1969-2012, 2d ed. McFarland. p. 958.

- Ess, Ramsey (20 September 2013). "Dick Cavett's Semi-Serious Talk with Graham Chapman". Splitsider. The Awl. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Hunter, I. Q.; Porter, Laraine (2012). British Comedy Cinema. Routledge. p. 181. ISBN 0-415-66667-8.

- McCabe, Bob (1999). Dark Knights and Holy Fools: The Art and Films of Terry Gilliam: From Before Python to Beyond Fear and Loathing. Universe. p. 106. ISBN 0-7893-0265-9.

- Birkinshaw, Julian; Ridderstråle, Jonas (2017). "Linking Strategy Back to Purpose". Fast/Forward: Make Your Company Fit for the Future. Stanford University Press. ISBN 1503602311.

- "Monty Python at the Movies". American Film Institute. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Canby, Vincent (31 March 1983). "MONTY PYTHON, 'THE MEANING OF LIFE'". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Ebert, Roger (1 April 1983). "Monty Python's The Meaning of Life Movie Review (1983),". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- Staff (31 December 1982). "Review: Monty Python's The Meaning of Life". Variety. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Siskel, Gene (April 1, 1983). "Python 'Meaning of Life' tingles with high-voltage shocks". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 1.

- Benson, Sheila (March 31, 1983). "Python's 'Life' Raunchy But Funny". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 1.

- Arnold, Gary (4 April 1983). "'Life' Without Meaning". The Washington Post: B1, B2.

- Jenkins, Steve (June 1983). "Monty Python's Meaning of Life". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 50 (593): 163.

- Nathan, Ian (1 March 2007). "Monty Python's The Meaning of Life Review". Empire. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- Chilton, Martin (20 April 2014). "Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, review". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- Maltin, Leonard (2014). Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. Penguin. ISBN 0698183614.

- "8 TV Shows and Comedy Stars Inspired by Monty Python". BBC America. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Monty Python's The Meaning of Life". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- "Festival de Cannes: Monty Python's The Meaning of Life". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- Dionne, E.J., Jr. (20 May 1983). "JAPANESE FILM AWARDED TOP PRIZE AT CANNES". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Original Song Written for a Film in 1984". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Murray, Noel (22 September 2003). "Monty Python's The Meaning Of Life (Special Edition DVD)". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- "Monty Python's The Meaning of Life: 2-Disc Collector's Edition". DVD Talk. 2 September 2003. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- Heilbron, Alexandra (8 October 2013). "Monty Python's The Meaning of Life 30th Anniversary Blu-ray". Tribute. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Monty Python's The Meaning of Life |