Money Heist

Money Heist (Spanish: La casa de papel, "The House of Paper") is a Spanish heist crime drama television series created by Álex Pina. The series traces two long-prepared heists led by the Professor (Álvaro Morte), one on the Royal Mint of Spain, and one on the Bank of Spain. The series was initially intended as a limited series to be told in two parts. It had its original run of 15 episodes on Spanish network Antena 3 from 2 May 2017 through 23 November 2017. Netflix acquired global streaming rights in late 2017. It re-cut the series into 22 shorter episodes and released them worldwide, beginning with the first part on 20 December 2017, followed by the second part on 6 April 2018. In April 2018, Netflix renewed the series with a significantly increased budget for 16 new episodes total. Part 3, with eight episodes, was released on 19 July 2019. Part 4, also with eight episodes, was released on 3 April 2020. A documentary involving the producers and the cast premiered on Netflix the same day, titled Money Heist: The Phenomenon (Spanish: La casa de papel: El Fenómeno). In July 2020, Netflix renewed the show for a fifth and final part.

| Money Heist | |

|---|---|

Part 1 and 2 title card | |

| Spanish | La casa de papel |

| Genre | |

| Created by | Álex Pina |

| Starring | |

| Theme music composer | Manel Santisteban |

| Opening theme | "My Life Is Going On" by Cecilia Krull |

| Composer(s) |

|

| Country of origin | Spain |

| Original language(s) | Spanish |

| No. of seasons | 2 (4 parts)[lower-alpha 1] |

| No. of episodes | 31 (list of episodes) |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) |

|

| Production location(s) |

|

| Cinematography | Migue Amoedo |

| Editor(s) |

|

| Camera setup | Single-camera |

| Running time | 67–77 minutes (Antena 3) 41–59 minutes (Netflix) |

| Production company(s) | |

| Distributor | Netflix |

| Release | |

| Original network |

|

| Picture format | 1080p (16:9 HDTV)

|

| Audio format | 5.1 surround sound |

| Original release | 2 May 2017 – present |

| External links | |

| Website | |

The series was filmed in Madrid, Spain. Significant portions of part 3 and 4 were also filmed in Panama, Thailand, and Italy (Florence). The narrative is told in a real-time-like fashion and relies on flashbacks, time-jumps, hidden character motivations, and an unreliable narrator for complexity. The series subverts the heist genre by being told from the perspective of a woman, Tokyo (Úrsula Corberó), and having a strong Spanish identity, where emotional dynamics offset the perfect strategic crime.

The series received several awards including best drama series at the 46th International Emmy Awards, as well as critical acclaim for its sophisticated plot, interpersonal dramas, direction, and for trying to innovate Spanish television. The Italian anti-fascist song "Bella ciao," which plays multiple times throughout the series, became a summer hit across Europe in 2018. By 2018, the series was the most-watched non-English language series and one of the most-watched series overall on Netflix,[4] with a particular resonance coming from viewers from Mediterranean Europe and the Latin world.

Premise

Set in Madrid, a mysterious man known as "The Professor" recruits a group of eight people, who choose cities for code-names, to carry out an ambitious plan that involves entering the Royal Mint of Spain, and escaping with €2.4 billion. After taking 67 people hostage inside the Mint, the team plans to remain inside for 11 days to print the money as they deal with elite police forces. In the events succeeding the initial heist, the group are forced out of hiding and find themselves preparing for a second heist, this time on the Bank of Spain, as they again deal with hostages and police forces.

Cast and characters

Main

- Úrsula Corberó as Silene Oliveira (Tokyo): a runaway robber until scouted by the Professor to participate in his plan; she also acts as an unreliable narrator.

- Álvaro Morte as Sergio Marquina (The Professor) / Salvador "Salva" Martín: the mastermind of the heist who assembled the group, and Berlin's brother.

- Itziar Ituño as Raquel Murillo (Lisbon): an inspector of the National Police Corps who is put in charge of the case until she joins the group in part 3.

- Pedro Alonso as Andrés de Fonollosa (Berlin): a terminally ill jewel thief and the Professor's second-in-command and brother.

- Paco Tous as Agustín Ramos (Moscow; parts 1–2; featured parts 3–4): a former miner turned criminal and Denver's father.

- Alba Flores as Ágata Jiménez (Nairobi): an expert in counterfeiting and forgery, in charge of printing the money and oversaw the melting the gold.

- Miguel Herrán as Aníbal Cortés (Rio): a young hacker.

- Jaime Lorente as Ricardo / Daniel[lower-alpha 2] Ramos (Denver): Moscow's son who joins him in the heist.

- Esther Acebo as Mónica Gaztambide (Stockholm): one of the hostages who is Arturo Román's secretary and mistress, carrying his child out of wedlock. During the robbery, she falls in love with Denver and becomes an accomplice to the group.

- Enrique Arce as Arturo Román: a hostage and the former Director of the Royal Mint of Spain.

- María Pedraza as Alison Parker (parts 1–2): a hostage and daughter of the British ambassador to Spain.

- Darko Perić as Mirko Dragic (Helsinki): a veteran Serbian soldier and Oslo's cousin.

- Kiti Mánver as Mariví Fuentes (parts 1–2; featured parts 3–4): Raquel's mother.

- Hovik Keuchkerian as Bogotá (parts 3–4): an expert in metallurgy who joins the robbery of the Bank of Spain.

- Rodrigo de la Serna as Martín Berrote (Palermo / The Engineer; parts 3–4): an old Argentine friend of Berlin's who planned the robbery of the Bank of Spain with him and assumed his place as commanding officer.

- Najwa Nimri as Alicia Sierra (parts 3–4): a pregnant inspector of the National Police Corps put in charge of the case after Raquel departed from the force.

- Luka Peroš as Marseille (part 4; featured part 3): a member of the gang who joins the robbery of the Bank of Spain.

- Belén Cuesta as Julia (Manila; part 4; featured part 3): godchild of Moscow and Denver's childhood friend. She is a trans woman who joins the gang and poses as one of the hostages during the robbery of the Bank of Spain.

- Fernando Cayo as Colonel Luis Tamayo (part 4; featured part 3): a member of the Spanish Intelligence who oversees Alicia's work on the case.

Recurring

- Roberto García Ruiz as Dimitri Mostovói / Radko Dragić[lower-alpha 3] (Oslo; parts 1–2; featured parts 3–4): a veteran Serbian soldier and Helsinki's cousin.

- Fernando Soto as Ángel Rubio (parts 1–2; featured parts 3–4): a deputy inspector and Raquel's second-in-command.

- Juan Fernández as Colonel Luis Prieto (parts 1–2; featured parts 3–4): a member of the Spanish Intelligence who oversees Raquel's work on the case.

- Anna Gras as Mercedes Colmenar (parts 1–2): Alison's teacher and one of the hostages.

- Fran Morcillo as Pablo Ruiz (part 1): Alison's schoolmate and one of the hostages.

- Clara Alvarado as Ariadna Cascales (parts 1–2): one of the hostages who works in the Mint.

- Mario de la Rosa as Suárez: the chief of the Grupo Especial de Operaciones.

- Miquel García Borda as Alberto Vicuña (parts 1–2; featured part 4): Raquel's ex-husband and a forensic examiner.

- Naia Guz as Paula Vicuña Murillo: Raquel and Alberto's daughter.

- José Manuel Poga as César Gandía (part 4; featured part 3): chief of security for the Bank of Spain who escapes from hostage and causes havoc for the group.

- Antonio Romero as Benito Antoñanzas (parts 3–4): an assistant to Colonel Luis Tamayo, who is persuaded by the Professor to do tasks for him.

- Pep Munné as Mario Urbaneja (featured parts 3–4): the governor of the Bank of Spain.

- Olalla Hernández as Amanda (featured parts 3–4): a hostage that Arturo rapes.

- Mari Carmen Sánchez as Paquita (featured parts 3–4): a hostage and a nurse who tends to Nairobi while she recovers.

- Carlos Suárez as Miguel Fernández (featured parts 3–4): a nervous hostage.

- Ramón Agirre as Benjamín (featured part 4): father of Manila who aids the Professor in his plan.

- Ahikar Azcona as Matías Caño (featured parts 3–4): a member of the group who largely guards the hostages.

- Antonio García Ferreras as himself (featured part 4): journalist.

Conception and writing

—Writer Esther Martinez Lobato, October 2018[11]

The series was conceived by screenwriter Álex Pina and director Jesús Colmenar during their years of collaboration since 2008.[12] After finishing their work on the Spanish prison drama Vis a vis (Locked Up), they left Globomedia to set up their own production company, named Vancouver Media, in 2016.[12][13] For their first project, they considered either filming a comedy or developing a heist story for television,[12] with the latter having never been attempted before on Spanish television.[14] Along with former Locked Up colleagues,[lower-alpha 4] they developed Money Heist as a passion project to try new things without outside interference.[11] Pina was firm about making it a limited series, feeling that dilution had become a problem for his previous productions.[15]

Initially entitled Los Desahuciados (The Evicted) in the conception phase,[15] the series was developed to subvert heist conventions and combine elements of the action genre, thrillers and surrealism, while still being credible.[12] Pina saw an advantage over typical heist films in that character development could span a considerably longer narrative arc.[16] Characters were to be shown from multiple sides to break the viewers' preconceptions of villainy and retain their interest throughout the show.[16] Key aspects of the planned storyline were written down at the beginning,[17] while the finer story beats were developed incrementally to not overwhelm the writers.[18] Writer Javier Gómez Santander compared the writing process to the Professor's way of thinking, "going around, writing down options, consulting engineers whom you cannot tell why you ask them that," but noted that fiction allowed the police to be written dumber when necessary.[18]

The beginning of filming was set for January 2017,[14] allowing for five months of pre-production.[19] The narrative was split into two parts for financial considerations.[19] The robbers' city-based code names, which Spanish newspaper ABC compared to the colour-based code names in Quentin Tarantino's 1992 heist film Reservoir Dogs,[20] were chosen at random in the first part,[21] although places with high viewership resonance were also taken into account for the new robbers' code names in part 3.[22] The first five lines of the pilot script took a month to write,[19] as the writers were unable to make the Professor or Moscow work as narrator.[15] Tokyo as an unreliable narrator, flashbacks and time-jumps increased the narrative complexity,[16] but also made the story more fluid for the audience.[19] The pilot episode required over 50 script versions until the producers were satisfied.[23][24] Later scripts would be finished once per week to keep up with filming.[19]

Casting

Casting took place late in 2016, spanning more than two months.[25] The characters were not fully fleshed out at the beginning of this process, and took shape based on the actors' performance.[26] Casting directors Eva Leira and Yolanda Serrano were looking for actors with the ability to play empathetic robbers with believable love and family connections.[27] Antena 3 announced the ensemble cast in March 2017[3] and released audition excerpts of most cast actors in the series' aftershow Tercer Grado and on their website.[26]

The Professor was designed as a charismatic yet shy villain who could convince the robbers to follow him and make the audience sympathetic to the robbers' resistance against the powerful banks.[28] However, developing the Professor's role proved difficult, as the character did not follow archetypal conventions[25] and the producers were uncertain about his degree of brilliance.[15] While the producers found his Salva personality early on,[15] they were originally looking for a 50-year-old Harvard professor type with the looks of Spanish actor José Coronado.[29][15] The role was proposed to Javier Gutiérrez, but he was already committed to starring in the film Campeones.[30] Meanwhile, the casting directors advocated for Álvaro Morte, whom they knew from their collaboration on the long-running Spanish soap opera El secreto de Puente Viejo, even though his prime time television experience was limited at that point.[29] Going through the full casting process and approaching the role through external analysis rather than personal experience, Morte described the professor as "a tremendous box of surprises" that "end up shaping this character because he never ceases to generate uncertainty," making it unclear for the audience if the character is good or bad.[25] The producers also found that his appearance of a primary school teacher gave the character more credibility.[15]

Pedro Alonso was cast to play Berlin, whom La Voz de Galicia would later characterize as a "cold, hypnotic, sophisticated and disturbing character, an inveterate macho with serious empathy problems, a white-collar thief who despises his colleagues and considers them inferior."[31] The actor's portrayal of the character was inspired by chance encounter Alonso had the day before receiving his audition script, with "an intelligent person" who was "provocative or even manipulative" to him.[32] Alonso saw high observation skills and an unusual understanding of his surroundings in Berlin, resulting in unconventional and unpredictable character behaviour.[31] Similarities between Berlin and Najwa Nimri's character Zulema in Pina's TV series Locked Up were unintentional.[33] The family connection between the Professor and Berlin were not in the original script but was built into the characters' backstory at the end of part 1 after Morte and Alonso had repeatedly proposed to do so.[34]

The producers found the protagonist and narrator, Tokyo, among the hardest characters to develop,[19] as they were originally looking for an older actress to play the character who had nothing to lose before meeting the Professor.[26] Úrsula Corberó eventually landed the role for bringing a playful energy to the table; her voice was heavily factored in during casting, as she was the first voice the audience hears in the show.[26] Jaime Lorente developed Denver's hallmark laughter during the casting process.[26] Two cast actors had appeared in previous TV series by Álex Pina: Paco Tous (Moscow) had starred in the 2005 TV series Los hombres de Paco, and Alba Flores (Nairobi) had starred in Locked Up. Flores was asked to play Nairobi without audition when Pina realised late in the conception phase that the show needed another female gang member.[15] For the role opposite to the robbers, Itziar Ituño was cast to play Inspector Raquel Murillo, whom Ituño described as a "strong and powerful woman in a world of men, but also sensitive in her private life".[35] She took inspiration from The Silence of the Lambs character Clarice Starling, an FBI student with a messy family life who develops sympathies for a criminal.[36]

The actors learned of the show's renewal by Netflix before the producers contacted them to return.[37] In October 2018, Netflix announced the cast of part 3; the returning main cast included Pedro Alonso, raising speculation about his role in part 3.[38] Among the new cast members were Argentine actor Rodrigo de la Serna, who saw a possible connection between his character's name and the Argentine football legend Martín Palermo,[39] and Locked Up star Najwa Nimri. Cameo scenes of Brazilian football star, and fan of the series, Neymar, as a monk were filmed for part 3, but were excluded from the stream without repercussions to the narrative until judicial charges against him had been dropped in late August 2019.[40][18] A small appearance by Spanish actress Belén Cuesta in two episodes of part 3 raised fan and media speculation about her role in part 4.[41]

Design

The show's look and atmosphere were developed by creator Álex Pina, director Jesús Colmenar, and director of photography Migue Amoedo, according to La Vanguardia "the most prolific television trio in recent years".[42] Abdón Alcañiz served as art director.[43] Their collaboration projects usually take a primary colour as a basis;[43] Money Heist had red as "one of the distinguishing features of the series"[44] that stood over the gray sets.[45] Blue, green and yellow were marked as a forbidden colour in production design.[45] To achieve "absolute film quality", red tones were tested with different types of fabrics, textures and lighting.[46] The iconography of the robbers' red jumpsuits mirrored the yellow prison dress code in Locked Up.[44] For part 3, the Italian retail clothing company Diesel modified the red jumpsuits to better fit the body and launched a clothing line inspired by the series.[45] Salvador Dalí was chosen as the robbers' mask design because of Dalí's recognisable visage that also serves as an iconic cultural reference to Spain; Don Quixote as an alternative mask design was discarded.[47] This choice sparked criticism by the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation for not requesting the necessary permissions.[27]

To make the plot more realistic, the producers requested and received advice from the national police and the Spanish Ministry of Interior.[48][49] The robbers' banknotes were printed with permission of the Bank of Spain and had an increased size as an anti-counterfeit measure.[48] The greater financial backing of Netflix for part 3 allowed for the build of over 50 sets across five basic filming locations world-wide.[50] Preparing a remote and uninhabited island in Panama to represent a robber hide-out proved difficult, as it needed to be cleaned, secured and built on, and involved hours-long travelling with material transportation.[46] The real Bank of Spain was unavailable for visiting and filming for security reasons, so the producers recreated the Bank on a two-level stage by their own imagining, taking inspiration from Spanish architecture of the Francisco Franco era.[46] Publicly available information was used to make the Bank's main hall set similar to the real location. The other interior sets were inspired by different periods and artificially aged to accentuate the building's history.[50] Bronze and granite sculptures and motifs from the Valle de los Caídos were recreated for the interior,[46] and over 50 paintings were painted for the Bank to emulate the Ateneo de Madrid.[50]

Filming

_02.jpg)

Parts 1 and 2 were filmed back-to-back in the greater Madrid region from January until August 2017.[25][51][23] The pilot episode was recorded in 26 days,[48] while all other episodes had around 14 filming days.[16] Production was split into two units to save time, with one unit shooting scenes involving the Professor and the police, and the other filming scenes with the robbers.[19] The main storyline is set in the Royal Mint of Spain in Madrid, but the exterior scenes were filmed at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) headquarters for its passing resemblance to the Mint,[48] and on the roof of the Higher Technical School of Aeronautical Engineers, part of the Technical University of Madrid.[51] The hunting estate where the robbers plan their coup was filmed at the Finca El Gasco farm estate in Torrelodones.[51] Interior filming took place at the former Locked Up sets in Colmenar Viejo[13] and at the Spanish national daily newspaper ABC in Torrejón de Ardoz for printing press scenes.[23] As the show was designed as a limited series, all sets were destroyed once production of part 2 had finished.[19]

Parts 3 and 4 were also filmed back-to-back,[52] with 21 to 23 filming days per episode.[16] Netflix announced the start of filming on 25 October 2018,[28] and filming of part 4 ended in August 2019.[53] In 2018, Netflix had opened their first European production hub in Tres Cantos near Madrid for new and existing Netflix productions;[54] main filming moved there onto a set three times the size of the set used for parts 1 and 2.[55] The main storyline is set in the Bank of Spain in Madrid, but the exterior was filmed at the Ministry of Development complex Nuevos Ministerios.[55] A scene where money is dropped from the sky was filmed at Callao Square.[51] Ermita de San Frutos in Carrascal del Río served as the exterior of the Italian monastery where the robbers plan the heist.[45] The motorhome scenes of the Professor and Lisboa were filmed at the deserted Las Salinas beaches in Almería to make the audience feel that the characters are safe from the police although their exact location is undisclosed at first.[56] Underwater scenes inside the vault were filmed at Pinewood Studios in the United Kingdom.[57][22] The beginning of part 3 was also filmed in Thailand, on the Guna Yala islands in Panama, and in Florence, Italy,[46] which helped to counter the claustrophobic feeling of the first two parts,[16] but was also an expression of the plot's global repercussions.[58]

Music

The series' theme song, "My Life Is Going On," was composed by Manel Santisteban, who also served as composer on Locked Up. Santisteban approached Spanish singer, Cecilia Krull, to write and perform the lyrics, which are about having confidence in one's abilities and the future.[59] The theme song is played behind a title sequence featuring paper models of major settings from the series.[59] Krull's main source of inspiration was the character Tokyo in the first episode of the series, when the Professor offers her a way out of a desperate moment.[60] The lyrics are in English as the language that came naturally to Krull at the time of writing.[60]

The Italian anti-fascist song "Bella ciao" plays multiple times throughout the series and accompanies two emblematic key scenes: At the end of the first part the Professor and Berlin sing it in preparation for the heist, embracing themselves as resistance against the establishment,[61] and in the second part it plays during the thieves' escape from the Mint, as a metaphor for freedom.[62] Regarding the use of the song, Tokyo recounts in one of her narrations, "The life of the Professor revolved around a single idea: Resistance. His grandfather, who had fought against the fascists in Italy, taught him the song, and he taught us."[62] The song was brought to the show by writer Javier Gómez Santander. He had listened to "Bella ciao" at home to cheer him up, as he had grown frustrated for not finding a suitable song for the middle of part 1.[18] He was aware of the song's meaning and history and felt it represented positive values.[18] "Bella ciao" became a summer hit in Europe in 2018, mostly due to the popularity of the series and not the song's grave themes.[61]

Episodes

| Season[lower-alpha 1] | Part[lower-alpha 1] | Episodes | Originally released | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First released | Last released | Network | |||||

| 1 | 1 | 15[lower-alpha 5] | 9 | 2 May 2017 | 27 June 2017 | Antena 3 | |

| 2 | 6 | 16 October 2017 | 23 November 2017 | ||||

| 2 | 3 | 16 | 8 | 19 July 2019 | Netflix | ||

| 4 | 8 | 3 April 2020 | |||||

Season 1: Parts 1 and 2 (2017)

Part 1 begins with the aftermath of a failed bank robbery by a woman named "Tokyo," as a man called the "Professor" saves her from being caught by the police and proposes her a heist of drastic proportions. After a brief outline of the planned heist, the story jumps to the beginning of a multi-day assault on the Royal Mint of Spain in Madrid. The eight robbers are code-named after cities: Tokyo, Moscow, Berlin, Nairobi, Rio, Denver, Helsinki, and Oslo. Dressed in red jumpsuits with a mask of the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí, the group of robbers take 67 hostages as part of their plan to print and escape with €2.4 billion through a self-built escape tunnel. The Professor heads the heist from an external location. Flashbacks throughout the series show the five months of preparation in an abandoned hunting estate in the Toledo countryside; the robbers are not to share personal information nor engage in personal relationships, and the assault shall be without bloodshed.

Throughout parts 1 and 2, the robbers inside the Mint have difficulties sticking to the pre-defined rules, and face uncooperative hostages, violence, isolation, and mutiny. Tokyo commentates on the events through voice-overs. While Denver pursues a love affair with the hostage Mónica Gaztambide, inspector Raquel Murillo of the National Police Corps negotiates with the Professor on the outside and begins an intimate relationship with his alter ego "Salva." The Professor's identity is repeatedly close to being uncovered, until Raquel realises his true identity, but is emotionally unable and unwilling to hand him over to the police. At the end of part 2, after 128 hours, the robbers escape successfully from the Mint with €984 million printed, but at the cost of the lives of Oslo, Moscow and Berlin. One year after the heist, Raquel finds a series of postcards left by the Professor, who wrote the coordinates for a location in Palawan in the Philippines, where she reunites with him.

Season 2: Parts 3 and 4 (2019–20)

Part 3 begins two to three years after the heist on the Royal Mint of Spain, showing the robbers enjoying their lives paired-up in diverse locations. However, when Europol captures Rio with an intercepted phone, the Professor picks up Berlin's old plans to assault the Bank of Spain to force Europol to hand over Rio to prevent his torture. He and Raquel (going by "Lisbon") get the gang, including Mónica (going by "Stockholm"), back together, and enlist three new members: Bogotá, Palermo, and Marseille, with Palermo in charge. Flashbacks to the Professor and Berlin outline the planned new heist and their different approaches to love. The disguised robbers sneak into the heavily guarded bank, take hostages and eventually gain access to the gold and state secrets. At the same time, the Professor and Lisbon travel in an RV and then an ambulance while communicating with the robbers and the police. A breach in the bank is thwarted, forcing the police, led by Colonel Luis Tamayo and pregnant inspector Alicia Sierra, to release Rio to the robbers. Nairobi gets gravely injured by a police-inflicted sniper shot in the chest, and the police catch Lisbon. With another police assault on the bank incoming, and believing Lisbon to have been executed by the police, the Professor radios Palermo and declares DEFCON 2 on the police. Part 3 concludes by showing Lisbon alive and in custody, and Tokyo narrating that the Professor had fallen for his own trap and that "the war had begun."

Part 4 begins with the robbers rushing to save Nairobi's life. While Tokyo stages a coup d'état and takes over command from Palermo, the Professor and Marseille deduce that Lisbon must still be alive and being interrogated by Sierra in a tent outside of the bank. They persuade Tamayo's assistant, Antoñanzas, to help them, and the Professor can establish a 48-hour truce with the police. As the group manages to save Nairobi's life, the restrained Palermo creates chaos to reestablish his command by colluding with Gandía, the restrained chief of security for the Bank of Spain. Gandía escapes, begins communications with the police from within a panic room inside the bank, and participates in a violent cat-and-mouse game with the gang. Palermo regains the trust of the group and rejoins them. Gandía shoots Nairobi in the head, killing her instantly, but the gang later recapture him. As the police prepare another assault on the bank, the Professor exposes the unlawful torture of Rio and the holding of Lisbon to the public. Due to this revelation, Sierra is fired and begins a pursuit of the Professor on her own. The Professor enlists external help to free Lisbon after she is transferred to the Supreme Court. Part 4 concludes with Lisbon rejoining the gang within the bank, and with Sierra finding the Professor's hideout, holding him at gunpoint.

Themes and analysis

The series was noted for its subversions of the heist genre. While heist films are usually told with a rational male Anglo-centric focus, the series reframes the heist story by giving it a strong Spanish identity and telling it from a female perspective through Tokyo.[65] The producers regarded the cultural identity as an important part of the personality of the series, as it made the story more relatable for viewers.[22] They also avoided adapting the series to international tastes,[22] which helped to set it apart from the usual American TV series[66] and raised international awareness of Spanish sensibilities.[22] Emotional dynamics like the passion and impulsivity of friendship and love offset the perfect strategic crime for increased tension.[65][52] Nearly all main characters, including the relationship-opposing Professor, eventually succumb to love,[58] for which the series received comparisons to telenovelas.[4][67] Comedic elements, which were compared to Back to the Future[25] and black comedy,[55] also offset the heist tension.[68] The heist film formula is subverted by the heist starting straight after the opening credits instead of lingering on how the gang is brought together.[2]

With the series being set after the financial crisis of 2007–2008, which resulted in severe austerity measures in Spain,[67] critics argued that the series was an explicit allegory of rebellion against capitalism,[4][69] including The Globe and Mail, who saw the series as "subversive in that it's about a heist for the people. It's revenge against a government."[67] According to Le Monde, the Professor's teaching scenes in the Toledo hunting estate, in particular, highlighted how people should seek to develop their own solutions for the fallible capitalist system.[69] The show's Robin Hood analogy of robbing the rich and giving to the poor received various interpretations. El Español argued that the analogy made it easier for viewers to connect with the show, as modern society tended to be tired of banks and politics already,[66] and the New Statesman said the rich were no longer stolen from but undermined at their roots.[4] On the other hand, Esquire's Mireia Mullor saw the Robin Hood analogy as a mere distraction strategy for the robbers, as they initially did not plan to use the money from their first heist to improve the quality of life of regular people; for this reason, Mullor also argues that the large following for the robbers in part 3 was not understandable even though they represented a channel for the discontent of those bearing economic and political injustices.[70]

The characters were designed as multi-dimensional and complementary antagonists and antiheroes whose moralities are ever-changing.[19] Examples include Berlin, who shifts from a robber mistreating hostages, to one of the series' most beloved characters.[19] There is also the hostage Mónica Gaztambide, as well as inspector Raquel Murillo, who eventually join the cause of the robbers.[19] Gonzálvez of The Huffington Post finds that an audience may think of the robbers as evil at first for committing a crime, but as the series progresses it marks the financial system as the true evil and suggests the robbers have ethical and empathetic justification for stealing from an overpowered thief.[71] Najwa Nimri, playing inspector Sierra in part 3, said that "the complex thing about a villain is giving him humanity. That's where everyone gets alarmed when you have to prove that a villain also has a heart". She added that the amount of information and technology that surrounds us is allowing us to verify that "everyone has a dark side."[71] The series leaves it to the audience to decide who is good or bad, as characters are "relatable and immoral" at various points in the story.[19] Pina argued that it was this ability to change the view that made the series addictive and marked its success.[19]

With the relative number of female main characters in TV shows generally on the rise,[19] the series gives female characters the same attention as men, which the BBC regarded as an innovation for Spanish television.[72] While many plot lines in the heist series still relate to males,[19] the female characters become increasingly aware of gender-related issues, such as Mónica arguing in part 3 that women, just like men, could be robbers and a good parent.[73] Critics further examined feminist themes and a rejection of machismo[73] in the series through Nairobi and her phrase "The matriarchy begins" in part 2,[74] and a comparative scene in part 3, where Palermo claims a patriarchy in a moment that, according to CNET, is played for laughs.[75] La Vanguardia challenged any female-empowering claims in the series, as Úrsula Corberó (Tokyo) was often shown scantily clad,[76] and Esquire criticized how characters' relationship problems in part 3 were often portrayed to be the women's fault.[70] Alba Flores (Nairobi) saw no inherent feminist plot in the series, as women only take control when it suits the story,[74] whilst Esther Acebo (Mónica) described any feminist subtext in the show as not being vindicative.[77]

Broadcast and release

Original broadcast

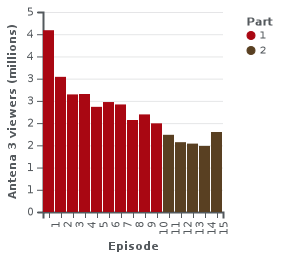

Part 1 aired on free-to-air Spanish TV channel Antena 3 in the Wednesday 10:40 p.m. time slot from 2 May 2017 till 27 June 2017.[48] Part 2 moved to the Monday 10:40 p.m. time slot and was broadcast from 16 October 2017 till 23 November 2017,[80] with the originally planned 18-21 episodes cut down to 15.[18][81] As the series was developed with Spanish prime-time television in mind,[12] the episodes had a length of around 70 minutes, as is typical for Spanish television.[82] The first five episodes of part 1 were followed by an aftershow entitled Tercer Grado (Third Grade).[26]

Despite boycott calls after Itziar Ituño (Raquel Murillo) had protested against the accommodations of ETA prisoners of her home Basque Country in March 2016,[83] the show had the best premiere of a Spanish series since April 2015,[84] with more than four million viewers and the majority share of viewers in its timeslot, almost double the number of the next highest-viewed station/show.[72] The show received good reviews and remained a leader in the commercial target group for the first half of part 1,[84] but the viewership eventually slipped to lower figures than expected by the Antena 3 executives.[85] Argentine newspaper La Nación attributed the decrease in viewer numbers to the change in time slots, the late broadcast times and the summer break between the parts.[24] Pina saw the commercial breaks as responsible, as they disrupted the narrative flow of the series that otherwise played almost in real time, even though the breaks were factored in during writing.[82] La Vanguardia saw the interest only waning among the conventional audience, as the plot unfolded too slowly at the rate of one episode per week.[42] Writer Javier Gómez Santander regarded the series' run on Antena 3 as a "failure" in 2019, as the ratings declined to "nothing special", but commended Antena 3 for making a series that did not rely on typical stand-alone episodes.[18]

Netflix acquisition

Part 1 was made available on Netflix Spain on 1 July 2017, like other series belonging to Antena 3's parent media group Atresmedia.[86] In December 2017, Netflix acquired the exclusive global streaming rights for the series.[72][86] Netflix re-cut the series into 22 episodes of around 50 minutes length.[82] Cliffhangers and scenes had to be divided and moved to other episodes, but this proved less drastic than expected because of the series' perpetual plot twists.[82] Netflix dubbed the series and renamed it from La casa de papel to Money Heist for distribution in the English-speaking world,[72] releasing the first part on 20 December 2017 without any promotion.[18][23] The second part was made available for streaming on 6 April 2018.[23] Pina assessed the viewer experience on Antena 3 versus Netflix as "very different", although the essence of the series remained the same.[82]

—Writer Javier Gómez Santander, September 2019[18]

Without a dedicated Netflix marketing campaign,[47] the series became the most-watched non-English language series on Netflix in early 2018, within four months of being added to the platform, to the creators' surprise.[87][4] This prompted Netflix to sign a global exclusive overall deal with Pina shortly afterwards.[88] Diego Ávalos, director of original content for Netflix in Europe, noted that the series was atypical in being watched across many different profile groups.[89] Common explanations for the drastic differences in viewership between Antena 3 and Netflix were changed consumption habits of series viewers,[82][18] and the binge-watching potential of streaming.[42][82] Pina and Sonia Martínez of Antena 3 would later say that the series, with its high demand of viewer attention, unknowingly followed the video-on-demand format from the beginning.[82] Meanwhile, people in Spain would discover the series on Netflix, unaware of its original Antena 3 broadcast.[82]

Renewal

In October 2017, Álex Pina said that part 2 had remote but intentional spin-off possibilities, and that his team was open to continue the robbers' story in the form of movies or a Netflix renewal.[90] Following the show's success on the streaming platform, Netflix approached Pina and Atresmedia to produce new chapters for the originally self-contained story. The writers withdrew themselves for more than two months to decide on a direction,[46] creating a bible with central ideas for new episodes in the process.[28] The crucial factors in accepting Netflix' deal were the creators recognising that characters still had things to say, and having the opportunity to deviate from the perfectly orchestrated heist of the first two parts.[52] Adamant that the story should be set in Spain again,[55] the producers wanted to make it a sequel rather than a direct continuation, and expand on the familiarity and affection between the characters instead of the former group of strangers.[12] Rio's capture was chosen as the catalyst to get the gang back together because he as the narrator's boyfriend represented the necessary emotional factor for the renewal not to be "suicide."[91]

Netflix officially renewed the series for the third part with a considerably increased budget on 18 April 2018,[21] which might make part 3 the most expensive series per episode in Spanish television history, according to Variety.[16] As writing was in progress, Pina stated in July 2018 that he appreciated Netflix' decision to make the episodes 45 to 50 minutes of length, as the narrative could be more compressed and international viewers would have more freedom to consume the story in smaller parts.[47] With Netflix' new push to improve the quality and appeal of its English-language versions of foreign shows, and over 70 percent of viewers in the United States choosing dubs over subtitles for the series, Netflix hired a new dubbing crew for part 3 and re-dubbed the first two parts accordingly.[1] Part 3, consisting of eight episodes, was released on 19 July 2019;[52] the first two episodes of part 3 also had a limited theatrical release in Spain one day before.[16]

In August 2019, Netflix announced that part 3 was streamed by 34 million household accounts within its first week of release, of which 24 million finished the series within this period,[68] thereby making it one of the most-watched productions on Netflix of all time, regardless of language.[92] Netflix had an estimated 148 million subscribers world-wide in mid-2019.[93] In October 2019, Netflix ranked Money Heist as their third most-watched TV series for the past twelve months,[94] and named it as the most-watched series across several European markets in 2019, including France, Spain and Italy, though not the UK.[95] Twitter ranked the show fourth in its "Top TV shows worldwide" of 2019.[96]

Filming of an initially unannounced fourth part of eight episodes ended in August 2019.[53][52] Álex Pina and writer Javier Gómez Santander stated that unlike part 3, where the intention was to re-attract the audience with high-energy drama after the move to Netflix, the story of part 4 would unfold slower and be more character-driven.[97] At another occasion, Pina and executive producer Esther Martínez Lobato teased part 4 as the "most traumatic [part] of all" because "this much tension has to explode somewhere".[98] Alba Flores (Nairobi) said the scriptwriters had previously made many concessions to fans in part 3, but would go against audience wishes in part 4 and that "anyone who loves Nairobi will suffer".[99] According to Pedro Alonso (Berlin), the focus of part 4 would be on saving Nairobi's life and standing by each other to survive.[99] Part 4 was released on 3 April 2020;[100] a documentary involving the producers and the cast premiered on Netflix the same day, titled Money Heist: The Phenomenon.[101]

Future

In October 2019, the online editions of Spanish newspapers ABC and La Vanguardia re-reported claims by the Spanish website formulatv.com that Netflix had renewed the series for a fifth part, and that pre-production had already begun.[102][103][104] In November 2019, La Vanguardia quoted director Jesús Colmenar's statement "That there is going to be a fifth [part] can be said", and that the new part would be filmed after Vancouver Media's new project Sky Rojo.[56] Colmenar also stated that there have been discussions with Netflix about creating a spin-off of the series,[56] as well as Pina.[105] In an interview in December 2019, Pina and Martínez Lobato would not discuss the possibility of a fifth part because of confidentiality contracts, and only said that "Someone knows there will be [a part 5], but we don't."[98]

On 31 July 2020, Netflix renewed the show for a fifth and final part.[106]

Reception

Public response

After the move to Netflix, the series remained the most-followed series on Netflix for six consecutive weeks and became one of the most popular series on IMDb.[82] It regularly trended on Twitter world-wide, largely because celebrities commented on it, such as football players Neymar and Marc Bartra, American singer Romeo Santos,[23] and author Stephen King.[75] While users flooded social networks with media of themselves wearing the robbers' outfit,[23] the robbers' costumes were worn at the Rio Carnival, and Dalí icons were shown on huge banners in Saudi Arabia football stadiums.[82] Real footage of these events would later be shown in part 3 as a tribute to the show's international success.[107] The Musée Grévin in Paris added statues of the robbers to its wax museum in summer 2018.[4] The show's iconography was used prominently by third parties for advertising,[108] sports presentations,[109] and in porn.[110]

There have also been negative responses to the influence of the show. In numerous incidents, real heist men wore the show's red costumes and Dalì masks in their attacks or copied the fictional robbers' infiltration plans.[4][23][111] The robbers' costumes were banned at the 2019 Limassol Carnival Festival as a security measure as a result.[112] The series was used in an attack on YouTube, when hackers removed the most-played song in the platform's history, "Despacito", and left an image of the show instead.[23] In unrelated reports, a journalist from the Turkish state channel AkitTV and an Ankaran politician have both warned against the show for supposedly encouraging terrorism and being "a dangerous symbol of rebellion".[4]

Spanish newspaper El Mundo saw the public response as a reflection of the "climate of global disenchantment" where the robbers represent the "perfect antiheroes",[17] and the New Statesman explained the show's resonance with international audiences as coming from the "social and economic tensions it depicts, and because of the utopian escape it offers."[4] Viewer response was especially high in Mediterranean Europe and the Latin world, in particular Spain, Italy, France, Portugal, Brazil, Chile and Argentina,[52] so Spanish as a common language did not appear to be a unifying reason for the show's success.[18] Writer Javier Gómez Santander and actor Pedro Alonso (Berlin) rather argued that the Latin world used to feel at the periphery of global importance, but a new sentiment was coming that Spain could compete with the global players in terms of media production levels and give the rest of the world a voice.[68][18]

Critical reception

The series' beginning on Antena 3 was received well by Spanish media.[84] Nayín Costas of El Confidencial named the premiere a promising start that captivated viewers with "adrenaline, well-dosed touches of humor and a lot of tension," but considered it a challenge to maintain the dramatic tension for the remainder of the series.[113] While considering the pilot's voice-over narration unnecessary and the sound editing and dialogs lacking, Natalia Marcos of El País enjoyed the show's ensemble cast and the ambition, saying "It is daring, brazen and entertaining, at least when it starts. Now we want more, which is not little."[44] Reviewing the full first part, Marcos lauded the series for its outstanding direction, the musical selection and for trying to innovate Spanish television, but criticized the length and ebbing tension.[85] At the end of the series' original run, Nayín Costas of El Confidencial commended the series for its "high quality closure" that may make the finale "one of the best episodes of the Spanish season", but regretted that it aimed to satisfy viewers with a predictable happy ending rather than risk to "do something different, original, ambitious", and that the show was unable to follow in the footsteps of Pina's Locked Up.[114]

After the show's move to Netflix for its international release, Adrian Hennigan of the Israeli Haaretz said the series was "more of a twisty thriller than soapy telenovela, driven by its ingenious plot, engaging characters, tense flash points, pulsating score and occasional moments of humor", but taunted the English title "Money Heist" as bland.[2] In a scathing review, Pauline Bock of the British magazine New Statesman questioned the global hype of the series, saying that it was "full of plot holes, clichéd slow-motions, corny love stories and gratuitous sex scenes", before continuing to add that "the music is pompous, the voice-over irritating, and it's terribly edited".[4] John Doyle of The Globe and Mail praised parts 1 and 2 for the heist genre subversions; he also said that the series could be "deliciously melodramatic at times" with "outrageous twists and much passion" like a telenovela.[67] Jennifer Keishin Armstrong of the BBC saw the series' true appeal in the interpersonal dramas emerging through the heist between "the beautiful robbers, their beautiful hostages, and the beautiful authorities trying to negotiate with them."[72] David Hugendick of Die Zeit found the series "sometimes a bit sentimental, a little cartoonesque," and the drama sometimes too telenovela-like, but "all with a good sense for timing and spectacle."[115]

Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes gave part 3 an approval rating of 100% based on 12 reviews, with an average rating of 7/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "An audacious plan told in a non-linear fashion keeps the third installment moving as Money Heist refocuses on the relations between its beloved characters."[116] While lauding the technical achievements, Javier Zurro of El Español described the third part as "first-class entertainment" that was unable to transcend its roots and lacked novelty. He felt unaffected by the internal drama between the characters and specifically, disliked Tokyo's narration for its hollowness.[66] Alex Jiménez of Spanish newspaper ABC found part 3 mostly succeeding in its attempts to reinvent the show and stay fresh.[107] Euan Ferguson of The Guardian recommended watching part 3, as "it's still a glorious Peaky Blinders, just with tapas and subtitles,"[117] while Pere Solà Gimferrer of La Vanguardia found that the number of plot holes in part 3 could only be endured with constant suspension of disbelief.[76] Though entertained, Alfonso Rivadeneyra García of Peruvian newspaper El Comercio said the show does "what it does best: pretend to be the smartest boy in class when, in fact, it is only the most alive."[118]

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award | Category | Nominees | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Iris Award | Best screenplay | Álex Pina, Esther Martínez Lobato, David Barrocal, Pablo Roa, Esther Morales, Fernando Sancristóbal, Javier Gómez Santander | Won | [119] |

| FesTVal | Best direction in fiction | Jesús Colmenar, Alejandro Bazzano, Miguel Ángel Vivas, Álex Rodrigo | Nominated | [120] | |

| Best fiction (by critics) | Money Heist | Nominated | |||

| Fotogramas de Plata | Audience Award – Best Spanish Series | Money Heist | Won | [121] | |

| Best TV Actor | Pedro Alonso | Nominated | |||

| 2018 | International Emmy Awards | Best drama series | Money Heist | Won | [122] |

| Iris Award | Best actress | Úrsula Corberó | Won | [123] | |

| Best series | Money Heist | Nominated | |||

| MiM Series | Best direction | Jesús Colmenar, Alejandro Bazzano, Miguel Ángel Vivas, Álex Rodrigo | Won | [124] | |

| Golden Nymph | Best drama TV series | Money Heist | Won | [124] | |

| Spanish Actors Union | Best supporting television actor | Pedro Alonso | Won | [125] | |

| Best supporting television actress | Alba Flores | Nominated | |||

| Best television actor | Álvaro Morte | Nominated | |||

| Best TV cast actor | Jaime Lorente | Nominated | |||

| Best stand-out actress | Esther Acebo | Nominated | |||

| Premios Fénix | Best series | Money Heist | Nominated | [126] | |

| Festival de Luchon | Audience Choice Award | Money Heist | Won | [127] | |

| Jury Spanish Series Award | Money Heist | Won | |||

| Camille Awards | composer | Iván Martínez Lacámara | Nominated | [128] | |

| composer | Manel Santisteban | Nominated | |||

| Production Company | Vancouver Media | Nominated | |||

| Premios Feroz | Best Drama Series | Money Heist | Nominated | [129] | |

| Best Lead Actress in a Series | Úrsula Corberó | Nominated | |||

| Best Lead Actor in a Series | Álvaro Morte | Nominated | |||

| Best Supporting Actress in a Series | Alba Flores | Nominated | |||

| Best Supporting Actor in a Series | Paco Tous | Nominated | |||

| 2019 | Iris Award | Best actor | Álvaro Morte | Won | [130] |

| Best actress | Alba Flores | Won | |||

| Best direction | Jesús Colmenar, Álex Rodrigo, Koldo Serra, Javier Quintas | Won | |||

| Best fiction | Money Heist | Won | |||

| Best production | Cristina López Ferrar | Won | |||

| Spanish Actors Union | Lead Performance, Male | Álvaro Morte | Won | [131] | |

| Lead Performance, Female | Alba Flores | Nominated | |||

| Supporting Performance, Male | Jaime Lorente | Nominated | |||

| 2020 | Premios Feroz | Best drama series | Money Heist | Nominated | [132] |

| Best leading actor of a series | Álvaro Morte | Nominated | |||

| Best supporting actress in a series | Alba Flores | Nominated | |||

| Fotogramas de Plata | Audience Award – Best Spanish Series | Money Heist | Nominated | [133] | |

| Best TV Actor | Álvaro Morte | Nominated | |||

| Spanish Actors Union | Performance in a Minor Role, Male | Fernando Cayo | Won | [134] | |

| Lead Performance, Female | Alba Flores | Nominated | |||

| Premios Platinos for IberoAmerican Cinema | Best Miniseries or TV series | Money Heist | Won | [135] | |

| Best Male Performance in a Miniseries or TV series | Álvaro Morte | Won | |||

| Best Female Performance in in a Miniseries or TV series | Úrsula Corberó | Nominated | |||

| Best Female Supporting Performance in in a Miniseries or TV series | Alba Flores | Won |

Notes

- Some publications refer to "part" as "season."[63][64]

- The official website lists Denver's name as Daniel,[5] but in the show he has called himself Ricardo,[6] Dani[7] and Daniel.[8]

- The final closing credits reveal Oslo's mug shot with the name Dimitri Mostovói,[9] while his coffin shows the name Radko Dragic.[10]

- Locked Up and Money Heist share Álex Pina, Esther Martínez Lobato, Pablo Roa, and Esther Morales as writers; and Jesús Colmenar and Alex Rodrigo as directors.

- Part 1 was re-cut and released as 13 episodes on 20 December 2017 on Netflix, and Part 2 was re-cut and released as 9 episodes on 6 April 2018 on Netflix. See Money Heist § Netflix acquisition.

References

- Goldsmith, Jill (19 July 2019). "Netflix Wants to Make Its Dubbed Foreign Shows Less Dubby". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Hennigan, Adrian (7 April 2018). "Netflix's 'Money Heist' Will Steal Your Heart and Your Weekend". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Úrsula Corberó, Alba Flores and Álvaro Morte, protagonists of the fiction stories of 'La Casa de Papel'". antena3.com (in Spanish). 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Bock, Pauline (24 August 2018). "Spanish hit series 'La Casa de Papel' captures Europe's mood a decade after the crash". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Álvarez, Jennifer (25 November 2017). "Conoce los verdaderos nombres de la banda de atracadores de 'La casa de papel'" (in Spanish). antena3.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Part 2, episode 8". Money Heist. Event occurs at 36:50. Netflix.

- "Part 4, episode 5". Money Heist. Event occurs at 02:38. Netflix.

- "Part 4, episode 6". Money Heist. Event occurs at 19:55. Netflix.

- "Part 2, episode 9". Money Heist. Event occurs at 43:50. Netflix.

- "Part 2, episode 8". Money Heist. Event occurs at 24:00. Netflix.

- "Pier pressure". dramaquarterly.com. 15 October 2018. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Fernández, Juan (18 July 2019). "Los de 'La casa de papel' somos unos frikis" (in Spanish). elperiodico.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Jabonero, Daniel (22 May 2017). "Las dificultades que tiene FOX para producir una tercera temporada de 'Vis a Vis'" (in Spanish). elespanol.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Galv, Marian (3 January 2017). "'La Casa de Papel' ficha a Úrsula Corberó, Alba flores, Miguel Herrán y Paco Tous" (in Spanish). elconfidencial.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Gasparyan, Suren (16 October 2017). "Una 'casa de papel' con dos 'profesores'". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Lang, Jamie; Hopewell, John (15 July 2019). "'Money Heist' – 'La Casa de Papel' – Creator Alex Pina: 10 Takes on Part 3". Variety. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Elidrissi, Fati (19 July 2019). "La casa de papel: el fenómeno global español que retroalimenta la ficción". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Días-Guerra, Iñako (12 September 2019). "Javier Gómez Santander: "Los españoles no somos un buen ejército, pero como guerrilla somos la hostia"". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Pickard, Michael (29 June 2018). "Right on the Money". dramaquarterly.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Jiménez, Alex (16 July 2019). "Las claves del éxito imparable de "La casa de papel", que triunfa en todo el mundo de la mano de Netflix" (in Spanish). elperiodico.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Netflix confirma la cuarta temporada de 'La casa de papel'" (in Spanish). elperiodico.com. 27 June 2019. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Muela, Cesar (3 July 2019). ""Si 'La Casa de Papel' no hubiera estado en Netflix seguiríamos diciendo que no podemos competir con las series de fuera", Álex Pina, creador de la serie" (in Spanish). xataka.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "La historia detrás del éxito". elpais.com.co (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Ventura, Laura (16 June 2019). "De visita en el rodaje de la nueva Casa de papel" (in Spanish). lanacion.com.ar. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Soage, Noelia (28 June 2017). "Álvaro Morte: "La casa de papel va a marcar un antes y un después en la forma de tratar la ficción en este país"". ABC (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Tercer Grado (in Spanish). antena3.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- For the casting of Mónica and Arturo, see Tercer Grado 2: Accedemos en exclusiva a los castings de Enrique Arce y Esther Acebo en ‘La casa de papel’ (in Spanish). 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- For the casting of Helsinki and Denver, see Tercer Grado 3: Yolanda Serrano: "Denver existió en cuanto Jaime Lorente hizo el papel en el casting" (in Spanish). 16 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- For the casting of Tokyo and Rio, see Tercer Grado 4: Úrsula Corberó y Miguel Herrán se enfrentan a sus pruebas de casting (in Spanish). 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- For the casting of the Professor and Nairobi, see Tercer Grado 5: El casting de El Profesor: "Álvaro hace que quieras al personaje" (in Spanish). 1 June 2017. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "Eva Leira y Yolanda Serrano buscan el alma del actor para sus series" (in Spanish). 20minutos. 4 February 2019. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Ruiz de Elvira, Álvaro (13 July 2018). "La Casa de Papel, temporada 3: fecha de estreno en Netflix, tráiler, historia, sinopsis, personajes, actores y todo sobre la Parte 3" (in Spanish). laprensa.peru.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Pérez, Ana (25 January 2019). "Hablamos de series con 'El profesor' Álvaro Morte". Esquire (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ""La casa de papel": ¿quién es el actor que en realidad iba a ser el Profesor en lugar de Álvaro Morte?" (in Spanish). elcomercio.pe. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ""La casa de papel": ¿Quién es Berlín?". La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). 3 May 2017. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Perrin, Élisabeth (21 June 2018). "Pedro Alonso (La casa de papel) : "Berlin est à la fois cruel, héroïque et drôle"". Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "¿Cómo se planifica el atraco perfecto de 'La casa de papel'?". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 9 May 2017. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Bravo, Victória (6 August 2019). "La Casa de Papel: Atores revelam como mudaram o futuro da série mesmo sem o consentimento dos criadores" (in Portuguese). metrojornal.com.br. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Echites, Giulia (23 September 2018). "L'ispettore Murillo de 'La casa di carta': "La mia Raquel, donna forte in un mondo di uomini"". la Repubblica (in Italian). Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- "La tercera parte de la serie será un "bombazo": Itziar Ituño, actriz de "La casa de papel"" (in Spanish). wradio.com.co. 18 April 2018. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Livia, Michael (9 July 2018). ""La Casa de Papel": Itziar Ituño confirma que Raquel Murillo estará en la tercera temporada". as.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "'La Casa de Papel' Part 3 Goes into Production: Watch Video". Variety. 25 October 2018. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- Jiménez, Á. (30 July 2019). "El motivo por el que Palermo se llama así en "La casa de papel"". ABC. Spain. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- Galarraga Gortázar, Naiara (4 September 2019). "Neymar makes cameo in Netflix hit 'Money Heist' after rape case dropped". El País. Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Millán, Víctor (5 August 2019). "'La Casa de Papel': ¿Qué significa el papel de 'extra' de Belén Cuesta?". as.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Solà Gimferrer, Pere (19 July 2019). "Las claves del éxito de La casa de papel". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Viñas, Eugenio (12 June 2018). "Abdón Alcañiz, el valenciano tras la dirección de arte de algunas de las grandes series españolas". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Marcos, Natalia (3 May 2017). "'La casa de papel' se atreve". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Marcos, Natalia (12 July 2019). "'La casa de papel' derrocha poderío en su regreso". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Romero, Marta A. (17 June 2019). "'La casa de papel' nos abre sus puertas: te contamos cómo se ha rodado la tercera temporada con Netflix" (in Spanish). sensacine.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Ruiz de Elvira, Álvaro (13 July 2018). "Álex Pina: "Hay que hacer avances en la ficción, el espectador es cada vez más experto"". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Gago, Claudia (2 May 2017). "Todo el dinero de La casa de papel". El Mundo (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Molina, Berto (8 May 2017). "La Fábrica de la Moneda, molesta con la trama de la serie 'La casa de papel'" (in Spanish). elconfidencial.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Cordovez, Karen (11 July 2019). ""La Casa de Papel": los secretos del rodaje de la tercera temporada" (in Spanish). publimetro.cl. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Antigone Hall, Molly (7 August 2019). "Este es el Madrid real de 'La casa de papel'". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- ""La casa de papel", temporada 4: fecha de estreno en Netflix, qué pasará, actores, personajes, misterios y teorías" (in Spanish). elcomercio.pe. 10 August 2019. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "El Profesor desmiente su salida de La casa de papel". elespectador.com. 13 September 2019. Archived from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Hopewell, John (24 July 2018). "Netflix Launches Its First European Production Hub in Madrid". El País. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Marcos, Natalia (17 June 2019). ""La serie es más grande": dentro de la nueva temporada de 'La casa de papel'". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Director de 'La Casa de Papel': "La cuarta temporada va a ser más dura para el espectador"". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 17 November 2019. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

[Colmenar ha precisado que Sky Rojo] se producirá entre la cuarta y la quinta temporada de La Casa de Papel. "Que hay quinta temporada sí se puede decir", ha concluido entre risas tras ser advertido por Pedro Alonso.

- Flores, Alba (4 October 2019). Escena Favorita: Alba Flores – La Casa de Papel – Netflix (in Spanish). La Casa De Papel at youtube.com. Event occurs at 0:30. Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Contreras Fajardo, Lilian (18 July 2019). ""La Casa de Papel 3": robar oro para recuperar el amor" (in Spanish). elespectador.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Fernandez, Celia (22 July 2019). "The Theme Song for Netflix's La Casa de Papel/Money Heist Sends a Deliberate Message". oprahmag.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Rojas, Rodrigo (17 September 2019). "Cecilia Krull, la voz por detrás de la canción de "La casa de papel"" (in Spanish). vos.lavoz.com.ar. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Wiesner, Maria (2 August 2018). ""Wie "Bella Ciao" zum Sommerhit wurde". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Pereira, Alien (19 February 2018). ""Bella Ciao": música em "La Casa de Papel" é antiga, mas tem TUDO a ver com a série" (in Portuguese). vix.com. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Rosado, Juan Carlos (19 July 2019). "'La casa de papel': ocho artículos que hay que leer en el estreno de la tercera parte". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Pickard, Michael (29 June 2018). "Right on the Money". dramaquarterly.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Vidal, María (4 February 2019). "Álex Pina: "Con 'El embarcadero' tenía más presión que con 'La Casa de Papel'"" (in Spanish). lavozdeasturias.es. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Zurro, Javier (24 July 2019). "Netflix, no nos tomes el pelo: 'La Casa de Papel' no es para tanto" (in Spanish). elespanol.com. Archived from the original on 25 August 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Doyle, John (22 June 2018). "Three great foreign dramas on Netflix for a summer binge". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Lang, Jamie; Hopewell, John (1 August 2019). "Netflix's 'La Casa de Papel' – 'Money Heist' – Part 3 Smashes Records". Variety. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- Sérisier, Pierre (13 March 2018). "La Casa de Papel – Allégorie de la rébellion". Le Monde (in French). Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Mullor, Mireia (29 July 2019). "'La casa de papel': Los pros y contras de la tercera temporada en Netflix". Esquire (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Gonzálvez, Paula M. (28 June 2019). "Qué ha hecho bien 'La Casa de Papel' para convertirse en la serie de habla no inglesa más vista de la historia de Netflix" (in Spanish). huffingtonpost.es. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Keishin Armstrong, Jennifer (13 March 2019). "La Casa de Papel: Setting the bar for global television". bbc.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Martín, Cynthia (22 July 2019). "'La Casa de Papel 3' y su "me too" a la española". Esquire (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Cordovez, Karen (19 July 2019). "Nairobi" y el regreso de "La Casa de Papel": "Ahora el golpe es más ambicioso porque su finalidad es más grande" (in Spanish). publimetro.cl. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Puentes, Patricia (19 July 2019). "Money Heist 3 review: Bigger heist, higher stakes, same red coveralls". CNET. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Solà Gimferrer, Pere (9 August 2019). "Verdades incómodas de series (I): La lección de 'La casa de papel'". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Gonzálvez, Paula M. (8 July 2019). "Najwa Nimri ('La Casa de Papel'): "Tengo una experiencia clarísima con el éxito y si no te quieres exponer, no te expones"" (in Spanish). huffingtonpost.es. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- "AUDIENCIAS LA CASA DE PAPEL". formulatv.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ""La casa de papel": La serie española que arrasa en el mundo". 24horas.cl (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- Marcos, Natalia (15 October 2017). "El atraco perfecto llega a su fin". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 November 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "Álex Pina presenta 'La casa de Papel': 'Vis a Vis fue un enorme banco de pruebas'". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 2 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Marcos, Natalia (29 March 2018). "Por qué 'La casa de papel' ha sido un inesperado éxito internacional". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- Marcos, Natalia (4 May 2017). "Piden el boicot a 'La casa de papel' por el apoyo de una de sus protagonistas a Otegui y al acercamiento de presos etarras". ABC (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- "Una espectacular explosión y plan de fuga de los rehenes, en 'La casa de papel'". La Razón. 21 June 2017. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- Marcos, Natalia (24 November 2017). "'La casa de papel' ha ganado". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 August 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Netflix se fija, de nuevo, en una serie de Atresmedia: compra 'La casa de papel' para emitirla en todo el mundo". La Razón (in Spanish). 30 June 2017. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Netflix Q1 2018 Letter to Shareholders" (PDF). Netflix Investor Relations. 16 April 2018. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Hopewell, John (12 July 2018). "Netflix Signs Global Exclusive Overall Deal with 'La Casa de Papel' Creator Alex Pina". Variety. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Avendaño, Tom C. (2 August 2019). "'La casa de papel' logra más de 34 millones de espectadores y refuerza la estrategia internacional de Netflix". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "El creador de 'La casa de papel' se moja sobre su competencia: 'El Ministerio' y Bertín". elconfidencial.com (in Spanish). 16 October 2017. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ""La casa de papel," temporada 3: fecha de estreno en Netflix, cómo ver online, tráiler, actores, personajes y crítica". elcomercio.pe (in Spanish). 20 July 2019. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Pierce, Tilly (2 August 2019). "Money Heist smashes records as season 3 becomes Netflix's most watched show ever". Metro. UK. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Hopewell, John (12 July 2019). "Netflix's 'La Casa de Papel' Part 3 Wows at World Premiere". Variety. Archived from the original on 9 September 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- Koblin, John (17 October 2019). "Netflix's Top 10 Original Movies and TV Shows, According to Netflix". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Keslassy, Elsa (30 December 2019). "'La Casa de Papel' ('Money Heist') Tops Netflix's Charts in Key European Markets". Variety. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Filadelfo, Elaine (9 December 2019). "#ThisHappened in 2019". Twitter. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Ortiz, Paola (4 October 2019). "Creadores de La Casa de Papel nos cuentan cómo será la cuarta temporada". estilodf.tv (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Cortés, Helena (15 December 2019). "Álex Pina, creador de "La casa de papel": "Somos unos perturbados de la autocrítica"". ABC (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- Oliveira, Joana (10 December 2019). ""Quien quiera a Nairobi va a sufrir": El elenco de 'La casa de papel' promete sorpresas en la nueva temporada". El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "'Money Heist' Season 4 Coming to Netflix in April 2020". What's on Netflix. 8 December 2019. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- "'Money Heist: The Phenomenon' on Netflix Is An Hour-Long Doc 'Money Heist' Fans Should Not Miss". decider.com. 3 April 2020. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "La casa de papel tendrá 5ª temporada en Netflix". ABC (in Spanish). Spain. 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "'La casa de papel', renovada por una quinta temporada en Netflix". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 15 October 2019. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Netflix renueva 'La Casa de Papel' por una quinta temporada que volverá a contar con Álvaro Morte". formulatv.com (in Spanish). 14 October 2019. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "Money Heist season 5 and 6 already planned on Netflix before season 4 success". Metro. 7 April 2020. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- "'Money Heist': Netflix Renews Spanish Drama For Fifth & Final Season". deadline.com. 31 July 2020.

- Jiménez, Alex (25 June 2019). "Crítica de la tercera temporada de "La casa de papel": Asalto a golpe de billete... nunca mejor dicho". ABC (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- Santa Isabel - La Casa del Ahorro (in Spanish). Santa Isabel via youtube.com. 24 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Jiménez, Alex (9 August 2019). "¿Robarán la Liga? Tlaxcala FC presenta nueva camiseta a 'La Casa de Papel'". am.com.mx (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2019.

- Jiménez (27 September 2019). "Llega 'La casa de Raquel', la versión porno de "La casa de papel"" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Zamora, I. (7 August 2019). "El efecto "tóxico" de "La casa de papel"". ABC (in Spanish). Spain. Archived from the original on 16 September 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Rodriguez Martinez, Marta (14 November 2018). "Cypriot carnival bans costumes inspired by Netflix series 'Money Heist'". euronews.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Costas, Nayín (2 May 2017). "'La casa de papel' sube el listón con un impecable, y cinematográfico, piloto" (in Spanish). elconfidencial.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- Costas, Nayín (23 November 2017). "Final feliz en 'La casa de papel', un gran capítulo lastrado por la falta de sorpresa" (in Spanish). elconfidencial.com. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- Hugendick, David (10 April 2018). "Knackt das System!". Die Zeit (in German). Archived from the original on 18 October 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Money Heist: Part 3 (2019)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Ferguson, Euan (28 July 2019). "The week in TV: I Am Nicola; Orange Is the New Black; Keeping Faith; Money Heist". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- Rivadeneyra García, Alfonso (19 July 2019). ""La casa de papel" temporada 3: reseñamos sin SPOILERS los primeros 3 episodios" (in Spanish). elcomercio.pe. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- "XIX Premios Iris". academiatv.es (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "FesTVal Vitoria · Festival de la Televisión". festval.tv (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 17 December 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- "Fotogramas de Plata 2018" (in Spanish). fotogramas.es. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Ramos, Dino-Ray (20 November 2018). "'International Emmy Awards: 'Money Heist', 'Nevsu' Among Honorees – Complete Winners List". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "XX Premios Iris". academiatv.es. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "'La Casa de Papel' gana el premio a Mejor Serie Dramática en el Festival de Montecarlo". La Razón (in Spanish). 20 June 2018. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.