Muhammad Ghawth

Muhammad Ghawth (Ghouse,[1] Ghaus or Gwath[2][3]) Gwaliyari (1500 – 1562) was a 16th-century Sufi master of the Shattari order and Sufi saint, a musician,[4] and the author of Jawahir-i Khams (Arabic: al-Jawahir al-Khams, The Five Jewels).

Muhammad Ghawth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Muhammad Ghawth Gwaliyari 1500 |

| Died | 1562 (aged 61–62) Gwalior |

| Monuments | Tomb of Mohammad Guaz (ASI N-MP-147) |

| Occupation | Master of Suffism, author, musician |

| Relatives | Attar of Nishapur (ancestor) |

- See Ghaus Mohammad for the tennis player who reached the Wimbledon quarterfinals in 1939

Biography

Muhammad Ghawth was born in Gwalior, India in 1500; the name Gwaliyari means "of Gwalior". One of his ancestors was Fariduddin Attar of Nishapur.[5] In the preface of al-Jawahir al-Khams, he states that he wrote the book when he was 25 years old. In 1549 he travelled to Gujarat, when he was 50 years old. He stayed in Ahmedabad for ten years where he founded Ek Toda Mosque and preached.[6]

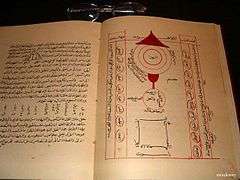

Ghawth translated the Amrtakunda from Sanskrit to Persian as the Bahr al-Hayat (The Ocean of Life), introducing to Sufism a set of yoga practices. According to the scholar Carl W. Ernst, in this "translation", Ghawth intentionally reframed these practices with great subtlety to identify "points of contact between the terminologies of Yoga and Sufism".[7]

Ghawth died in Gwalior in 1562.[8] His followers believed that he ascended to heaven and from there was able to direct help down to them; and further, that he was the "axial saint, the pivot of the universe".[8][9]

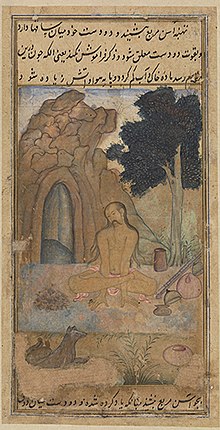

Ghawth's Jawahir al-Khams

Ghawth's Jawahir al-Khams Ghawth's tomb in Gwalior

Ghawth's tomb in Gwalior South-east view of tomb

South-east view of tomb

Works

- Jawahir-i-Khamsa (The Five Jewels) which was later translated to Arabic, al-Jawahir al-Khams, by the Mecca-based Shattari teacher Sibghat Allah (d. 1606 CE).[7]

- Bahr al-Hayat (The Ocean of Life), his translation and extension of Hawd al-Hayat (The Pool of Life), an Arabic translation of a lost Sanskrit text on yoga, the Amrtakunda.[10]

References

- Shattari lineage

- Idries Shah, The Sufis ISBN 0-86304-020-9 Octagon Press 1989 pp 335, 367

- Idries Shah, Tales of the Dervishes ISBN 0-900860-47-2 Octagon Press 1993 pp 111-112

- Wade, Bonnie C. (1998). Imaging Sound: An Ethnomusicological Study of Music, Art, and Culture in Mughal India (Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology). University Of Chicago Press. pp. 113–115. ISBN 0-226-86840-0. See google book search.

- "Muḥammad G̲h̲awt̲h̲ Gwaliyārī". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Achyut Yagnik (2 February 2011). Ahmedabad: From Royal city to Megacity. Penguin Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-81-8475-473-5.

- Ernst, Carl W. (1996). "Sufism and Yoga according to Muhammad Ghawth" (PDF). Sufi. 29 (Spring 1996): 9–13. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008.

- Kugle, Scott (July 2014). "Body Refined: The Eyes of Muhammad Ghawth". North Carolina University Press. doi:10.5149/9780807872772_kugle.10.

- Kugle, Scott A. (2003). "HEAVEN'S WITNESS: THE USES AND ABUSES OF MUḤAMMAD GHAWTH'S MYSTICAL ASCENSION". Journal of Islamic Studies. 14 (1, January 2003): 1–36. JSTOR 26199837.

- Ernst, Carl W. (2016). Chapter 8: Sufism and Yoga according to Muhammad Ghawth. Refractions of Islam in India: Situating Sufism and Yoga. Sage. pp. 121–129. ISBN 978-93-5150-964-6.

External links

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

List of sufis |

|

|