Minoan pottery

Minoan pottery has been used as a tool for dating the mute Minoan civilization. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, on Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

The pottery consists of vessels of various shapes, which as with other types of Ancient Greek pottery may be collectively referred to as "vases", and also "terracottas", small ceramic figurines, models of buildings and some other types. Some pieces, especially the cups of rhyton shape, overlap the two categories, being both vessels for liquids but essentially sculptural objects. Several pottery shapes, especially the rhyton cup, were also produced in soft stones such as steatite, but there was almost no overlap with metal vessels. Pottery sarcophagus chests were also made for cremated ashes, as in an example now in Hanover.

The finest achievements came in the Late Minoan period, with the palace pottery called Kamares ware, and the Late Minoan all-over patterned "Marine Style" and "Floral Style". These were widely exported around the Aegean civilizations and sometimes beyond, and are the high points of the Minoan pottery tradition.

The best and most comprehensive collection is in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH) on Crete (where most pieces illustrated are held).

Traditional chronology

| 3500–2900 BC[1] | EMI | Prepalatial |

| 2900–2300 BC | EMII | |

| 2300–2100 BC | EMIII | |

| 2100–1900 BC | MMIA | |

| 1900–1800 BC | MMIB | Protopalatial (Old Palace Period) |

| 1800–1750 BC | MMIIA | |

| 1750-1700 BC | MMIIB | Neopalatial (New Palace Period) |

| 1700–1650 BC | MMIIIA | |

| 1650–1600 BC | MMIIIB | |

| 1600–1500 BC | LMIA | |

| 1500–1450 BC | LMIB | Postpalatial (at Knossos; Final Palace Period) |

| 1450–1400 BC | LMII | |

| 1400–1350 BC | LMIIIA | |

| 1350–1100 BC | LMIIIB |

The traditional chronology for dating Minoan civilization was developed by Sir Arthur Evans in the early years of the 20th century AD. His terminology and the one proposed by Nikolaos Platon are still generally in use and appear in this article. For more details, see the Minoan chronology.

Evans classified fine pottery by the changes in its forms and styles of decoration. Platon concentrated on the episodic history of the Palace of Knossos. A new method, fabric analysis, involves geologic analysis of coarse and mainly non-decorated sherds as though they were rocks. The resulting classifications are based on composition of the sherds.[2]

Production and techniques

Little is known about the way the pottery was produced, but it was probably in small artisanal workshops, often clustered in settlements near good sources of clay for potting. For many, potting may well have been a seasonal activity, combined with farming, although the volume and sophistication of later wares suggests full-time specialists, and two classes of workshop, one catering to the palaces.[3] There is some evidence that women were also potters. Archaeologists seeking to understand the conditions of production have drawn tentative comparisons with aspects of both modern Cretan rural artisans and the better-documented Egyptian and Mesopotamian Bronze Age industries.[4] In Linear B the word for potter is "ke-ra-me-u".[5]

Technically, slips were widely used, with a variety of effects well understood. The potter's wheel appears to have been available from the MM1B, but other "handmade" methods of forming the body remained in use, and were needed for objects with sculptural shapes.[6] Ceramic glazes were not used, and none of the wares were fired to very high temperatures, remaining earthenware or terracotta. All of these characteristics remain true of later Greek pottery throughout its great period. The finest wares often have very thin-walled bodies. The excavation of an abandoned LM kiln at Kommos (the port of Phaistos), complete with its "wasters" (malformed pots), is developing understanding of the details of production.[7] The styles of pottery show considerable regional variation within Crete in many periods.[8]

Early Minoan

This is only a brief introduction to the topic of Early Minoan pottery, concentrating on some of the better-known styles; it should not be regarded as comprehensive. A variety of forms are known. The period is generally characterized by a large number of local wares with frequent Cycladic parallels or imports, suggesting a population of checkerboard ethnicity deriving from various locations in the eastern Aegean or even wider. The evidence is certainly open to interpretation, and none is decisive.

FN, EM I

Early Minoan pottery, to some extent, continued, and possibly evolved from, the local Final Neolithic[9] (FN) without a severe break. Many suggest that Minoan civilization evolved in-situ and was not imported from the East. Its other main feature is its variety from site to site, which is suggestive of localism of Early Minoan social traditions.

Studies of the relationship between EM I and FN have been conducted mainly in East Crete.[10] There the Final Neolithic has affinities to the Cyclades, while both FN and EM I settlements are contemporaneous, with EM I gradually replacing FN. Of the three possibilities, no immigration, total replacement of natives by immigrants, immigrants settling among natives, Hutchinson[11] takes a compromise view:

- "The Neolithic Period in Crete did not end in a catastrophe; its culture developed into that of the Bronze Age under pressure from infiltration of relatively small bands of immigrants from the south and east, where copper and bronze had long been in use."

Pyrgos Ware

EM I types include Pyrgos Ware,[12] also called "Burnished Ware". The major form was the "chalice", or Arkalochori Chalice, in which a cup combined with a funnel-shaped stand could be set on a hard surface without spilling. As the Pyrgos site was a rock shelter used as an ossuary, some hypothesize ceremonial usage]. This type of pottery was black, grey or brown, and burnished, with some sort of incised linear pattern. It may have imitated wood.

Incised Ware

Another EM I type, Incised Ware, also called Scored Ware, were hand-shaped, round-bottomed, dark-burnished jugs (Example) and bulbous cups and jars ("pyxes"). Favored decor was incised line patterns, vertical, horizontal or herring-bone. These pots are from the north and northeast of Crete and appear to be modeled after the Kampos Phase of the Grotta-Pelos early Cycladic I culture. Some have suggested imports or immigrations. See also Hagia Photia.

Agyios Onouphrios, Lebena

The painted parallel-line decoration of Ayios Onouphrios I Ware was drawn with an iron-red clay slip that would fire red under oxidizing conditions in a clean kiln but under the reducing conditions of a smoky fire turn darker, without much control over color, which could range from red to brown. A dark-on-light painted pattern was then applied.[13] From this beginning, Minoan potters already concentrated on the linear forms of designs, perfecting coherent designs and voids that would ideally suit the shape of the ware. Shapes were jugs, two-handled cups and bowls. The ware came from north and south central Crete, as did Lebena Ware of the same general types but decorated by painting white patterns over a solid red painted background (Example). The latter came from EM I tombs.

Koumasa and Fine Gray Ware

In EM IIA, the geometric slip-painted designs of Koumasa Ware seem to have developed from the wares of Aghios Onouphrios. The designs are in red or black on a light background. Forms are cups, bowls, jugs and teapots (Example: "Goddess of Myrtos"). Also from EM IIA are the cylindrical and spherical pyxides called Fine Gray Ware or just Gray Ware, featuring a polished surface with incised diagonals, dots, rings and semicircles.

File:Early Minoan pottery, 3000-2600 BC

File:Early Minoan pottery, 3000-2600 BC Bird shaped clay vessel from Koumasa, 2600–2300 BC, AMH.

Bird shaped clay vessel from Koumasa, 2600–2300 BC, AMH. Burnished cup, Kyparissi, 2600-1900 BC, AMH

Burnished cup, Kyparissi, 2600-1900 BC, AMH

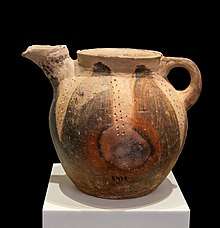

Vasiliki Ware

The EM IIA and IIB Vasiliki Ware, named for the Minoan site in eastern Crete,[14] has mottled glaze effects, early experiments with controlling color, but the elongated spouts drawn from the body and ending in semicircular spouts show the beginnings of the tradition of Minoan elegance (Examples 1, Examples 2). The mottling was produced by uneven firing of the slip-covered pot, with the hottest areas turning dark. Considering that the mottling was controlled into a pattern, touching with hot coals was probably used to produce it. The effect was paralleled in cups made of mottled stone.

Another style of "teapot", Vasiliki, 2400 - 2200 BC, AMH

Another style of "teapot", Vasiliki, 2400 - 2200 BC, AMH Vasiliki ware, jug, 2400-2200 BC

Vasiliki ware, jug, 2400-2200 BC Teapot in the white style, 2300–2000 BC, AMH

Teapot in the white style, 2300–2000 BC, AMH White style jug, 2300-1900 BC

White style jug, 2300-1900 BC- Other shapes; two "egg-cups" at rear

White style teapots, AMH

White style teapots, AMH

EM III Pottery

In the latest brief transition (EM III), wares in eastern Crete begin to be covered in dark slip with light slip-painted decor of lines and spirals; the first checkered motifs appear; the first petallike loops and leafy bands appear, at Gournia (Walberg 1986). Rosettes appear and spiral links sometimes joined into bands. These motifs are similar to those found on seals. In north central Crete, where Knossos was to emerge, there is little similarity: dark on light linear banding prevails; footed goblets make their appearance (Example).

Middle Minoan

Of the palace at Knossos and smaller ones like it at Phaestos, Mallia and elsewhere, Willetts says:[15]

- "These large palaces were central features of sizable cities... Apparently they were also administrative and religious centres of self-supporting regions of the island."

The rise of the palace culture, of the "old palaces" of Knossos and Phaistos and their new type of urbanized, centralized society with redistribution centers required more storage vessels and ones more specifically suited to a range of functions. In palace workshops, standardization suggests more supervised operations and the rise of elite wares, emphasizing refinements and novelty, so that palace and provincial pottery become differentiated.

The forms of the best wares were designed for table and service. In the palace workshops, the introduction from the Levant of the potter's wheel in MMIB enabled perfectly symmetrical bodies to be thrown from swiftly revolving clay.[16] The well-controlled iron-red slip that was added to the color repertory during MMI could be achieved only in insulated closed kilns that were free of oxygen or smoke.

Pithoi

Any population center requires facilities in support of human needs and that is true of the palaces as well. Knossos had extensive sanitation, water supply and drainage systems,[17] which is evidence that it was not a ceremonial labyrinth or large tomb. Liquid and granular necessities were stored in pithoi located in magazines, or storage rooms, and elsewhere. Pithoi make their earliest appearance just before MMI begins and continue into Late Minoan, becoming very rare by LMIII (Examples 1, Examples 2). About 400 pithoi were found at the palace of Knossos. An average pithos held about 1100 pounds of fluid. Perhaps because of the weight, pithoi were not stored on the upper floors.

New styles

New styles emerge at this time: an Incised Style, the tactile Barbotine ware, studded with knobs and cones of applied clay in bands, waves and ridges, sometimes reminiscent of sand-dollar tests and barnacle growth (Example), and the earliest stages of Kamares ware. Spirals and whorls are the favorite motifs of Minoan pottery from EM III onwards (Walberg). A new shape is the straight-sided cylindrical cup.

MMIA wares and local pottery imitating them are found at coastal sites in the eastern Peloponnese, though not more widely in the Aegean until MMIB; their influence on local pottery in the nearby Cyclades has been studied by Angelia G. Papagiannopoulou (1991). Shards of MMIIA pottery have been recovered in Egypt and at Ugarit.

Kamares Ware

Kamares Ware was named after finds in the cave sanctuary at Kamares on Mt. Ida in 1890. It is the first of the virtuoso polychrome wares of Minoan civilization, though the first expressions of recognizably proto-Kamares decor predate the introduction of the potter's wheel.

Finer clay, thrown on the wheel, permitted more precisely fashioned forms, which were covered with a dark-firing slip and exuberantly painted with slips in white, reds and browns in fluent floral designs, of rosettes or conjoined coiling and uncoiling spirals. Designs are repetitive or sometimes free-floating, but always symmetrically composed. Themes from nature begin here with octopuses, shellfish, lilies, crocuses and palm-trees, all highly stylized. The entire surface of the pot is densely covered, but sometimes the space is partitioned by bands. One variety features extravagantly thin bodies and is called Eggshell Ware (Example 1, Example 2).

Four stages of Kamares ware were identified by Gisela Walberg (1976), with a "Classic Kamares" palace style sited in MMII, especially in the palace complex of Phaistos. New shapes were introduced, with whirling and radiating motifs.(Examples 1, Examples 2, Examples 3, Examples 4, Examples 5, Examples 6, Examples 7, Examples 8, Examples 9, Examples 10)

Age of Efflorescence

In MMIIB, the increasing use of motifs drawn from nature heralded the decline and end of the Kamares style. The Kamares featured whole-field floral designs with all elements linked together (Matz). In MMIII patterned vegetative designs, the Patterned Style, began to appear. This phase was replaced by individual vegetative scenes, which marks the start of the Floral Style. Matz refers to the "Age of Efflorescence", which reached an apogee in LM IA. (Some would include Kamares Ware under the Floral Style.)

The floral style depicts palms and papyrus, with various kinds of lilies and elaborate leaves. It appears in both pottery and frescoes. One tradition of art criticism calls this the "natural style" or "naturalism" but another points out that the stylized forms and colors are far from natural. Green, the natural color of vegetation, appears rarely. Depth is represented by position around the main scene.

Late Minoan

LMI marks the highwater of Minoan influence throughout the southern Aegean (Peloponnese, Cyclades, Dodecanese, southwestern Anatolia). Late Minoan pottery was being widely exported; it has turned up in Cyprus, the Cyclades, Egypt and Mycenae.

Floral style

Fluent movemented designs drawn from flower and leaf forms, painted in reds and black on white grounds predominate, in steady development from Middle Minoan. In LMIB there is a typical all-over leafy decoration, for which first workshop painters begin to be identifiable through their characteristic motifs; as with all Minoan art, no name ever appears.

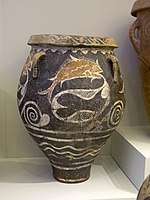

Marine style

In LMIB, the Marine Style also emerges; in this style, perhaps inspired by frescoes, the entire surface of a pot was covered with sea creatures, octopus, fish and dolphins, against a background of rocks, seaweed and sponges (Examples 1, Examples 2, Examples 3, Examples 4). The Marine Style is more free flowing with no distinct zones, because it shows sea creatures as floating, as they would in the ocean.[18] The Marine style was the last purely Minoan style; towards the end of LMIB, all the palaces except Knossos were violently destroyed, as were many of the villas and towns. This was because of the eruption of the volcano on the island of Thera during LMIA.[19] The explosion caused a tsunami which hit the northern coast of Crete,[20] and devastated the coastal settlements where the bulk of the palace complexes were located.[21]

Rhyta

Dated to LM IA and following also are conical rhyta, or drinking cups, in steatite and also imitated in ceramic. (Example) Some of the rhyta are ornate libation vessels, such as the noted "Bull's-head Rhyton" found at Knossos. The Bull's Head Rhyton, however, was a specific type of which many instances have been found. The bull's head is found in ceramic as well. Other noted stone vases of LM IA and II are the "Harvester Vase" View 1, View 3, View 4, from Hagia Triada, which depicts a harvest procession, "the Chieftain Cup", depicting a coming-of-age rite, the Boxer Rhyton (Hagia Triada), showing boxing scenes, the Sanctuary Rhyton, depicting a peak sanctuary to the "mistress of animals" and featuring birds and leaping goats, and others.

Marine Style "Ewer of Poros", 1500-1450 BC

Marine Style "Ewer of Poros", 1500-1450 BC Floral Style ewer from Phaistos, 1500-1450 BC

Floral Style ewer from Phaistos, 1500-1450 BC Floral Style ewer with papyrus, from Palaikastro, 1500-1450 BC

Floral Style ewer with papyrus, from Palaikastro, 1500-1450 BC Clay bulls head rhyton, Palaikastro, 1500-1450 BC, AMH

Clay bulls head rhyton, Palaikastro, 1500-1450 BC, AMH- Bull's-head Vase from LM II

Minoan-Mycenaean

Around 1450 BCE, the beginning of LM II, the Mycenaean Greeks must have moved into the palace of Knossos. They were well-established by 1400, if the Linear B tablets can be dated to then. The resulting LM II culture is not a break with the Minoan past. Minoan traditions continue under a new administration. However, the vase forms and designs became more and more Mycenaean in character with a large variety of decoration. Style names have multiplied and depend to some degree on the author. The names below are only a few of the most common. Some authors just use the name "Mycenaean Koine"; that is, the Late Minoan pottery of Crete was to some degree just a variety of widespread Mycenaean forms. The designs are found also on seals and ceilings, in frescoes and on other artifacts. Often Late Minoan pottery is not easily placed in sub-periods. In addition are imports from the neighboring coasts of the Mediterranean. Ceramic is not the only material used: breccia, calcite, chlorite, schist, dolomite and other colored and patterned stone were carved into pottery forms. Bronze ware appears imitating the ceramic ware.

Palace style

During LMII, Mycenean influence became apparent. The vase forms at Knossos are similar to those on the mainland. The Palace Style[22] showcased by them adapts elements of the previous styles but also adds features, such as the practice of confining decor in reserves and bands, emphasizing the base and shoulder of the pot and the movement towards abstraction (Examples 1, Examples 2, Examples 3). This style started in LM II and went on into LM III. The palace style was mostly confined to Knossos. In the late manifestation of the palace style, fluent and spontaneous earlier motifs stiffened and became more geometrical and abstracted. Egyptian motifs such as papyrus and lotus are prominent.

Plain and Close Styles

The Plain Style and Close Style developed in LM IIIA, B from the Palace Style. In the Close Style the Marine and Floral Styles themes continue, but the artist manifests the horror vacui or "dread of emptiness". The whole field of decoration is filled densely. (Examples). The Stirrup Jar is especially frequent.

The Middle East Style

IIIC

Subminoan

Finally, in the Subminoan period, the geometric designs of the Dorians become more apparent. (Example)

Discovery and recognition

Minoan wares were already familiar from finds on the Greek mainland, and export markets like Egypt, before it was realized that they came from Crete. In most 19th-century literature they are described as "Mycenaean", and the recognition and analysis of styles and periods had gone some way on this assumption. Only in the 1890s were the first finds on Crete recognised and published, from a cave at Kamares. These were found by a local archaeologist who allowed the young John Myres to publish them; Myres had realized that they were the same ware as finds in Egypt published by Flinders Petrie. For several decades analysis of Minoan pottery was essentially stylistic and typological, but in recent decades there has been a turn towards technical and socio-economic analysis.[23]

Written records of pots and pans

The Linear B tablets contain records of vessels made of various materials. The vessel ideograms are not so clear as to make correlation with discovered artifacts easy. Using a drawing of the "Contents of the Tomb of the Tripod Hearth" at Zafer Papoura from Evans' Palace of Minos,[24] which depicts LM II bronze vessels, many in the forms of ceramic ones, Ventris and Chadwick[25] were able to make a few new correlations.

| Ideogram[26] | Linear B[27] | Mycenaean Greek | Classical Greek | Etymology | Examples |

| 202 GOBLET? | di-pa | *dipas (sing) | depas (sing), cup, archaic large vessel. | C.Luvian tappas and H. Luvian (CAELUM)ti-pa-sº 'sky (perceived by Anatolians as a cup covering the flat Earth)' (Yakubovich 2010: 146) | 1, 2 (reproduction) |

| 207 TRIPOD AMPHORA | ku-ru-su-pa3 | Possibly *khrysyphaia[29] or possibly containing Semitic suppu "vase".[30] | ? | Possibly "gold and grey" if Greek or "golden vase" if Semitic | 1 (Early Cypriote) |

| 209 AMPHORA | a-pi-po-re-we | *amphiphorewes (pl) | amphiphoreus (sing), an amphora | "port-about" (Hoffman) | 1 |

| 210 STIRRUP JAR | ka-ra-re-we | *khlarewes (pl) | khlaron (sing), archaic oil jar | "yellow stuff" (Hoffman) | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| 211 WATER BOWL? | po-ti-[]-we | ? | ? | ? | |

| 212 WATER JAR? | u-do-ro | *hudroi (pl) | hydros (sing), a water-snake | "water (jars)" | 1 |

| 213 COOKING BOWL | i-po-no | *ipnoi (pl)[31] | ipnos (sing), a baking dish | "Dutch oven"[32] |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minoan pottery. |

- Poppy goddess, a LM figurine

- Thrapsano, then and now, a village known for pottery

Notes

- This chronology of Minoan Crete is the one used by Andonis Vasilakis in his book on Minoan Crete, published by Adam Editions in 2000, but other chronologies will vary, sometimes quite considerably (EM periods especially). Sets of different dates from other authors are set out at Minoan chronology

- Fabric Research and Analysis, The Spakia Survey: Internet Edition.

- Traunmueller, 341-350

- Traunmueller, 341-350

- Traunmueller, 348

- Oxford, 409

- A LM IA Ceramic Kiln in South-Central Crete, Joseph W. Shaw et al., Hesperia Supplement 30, 2001.

- Oxford, Chapter 30 summarizes these.

- This term dating from the late 20th century means the very last, transitional phase of the Neolithic, in which stone tools were in use along with elements of the succeeding metal age. The terms, "Chalcolithic", "Copper Age" and "Sub-Neolithic", clearly fall into this category. They are used in this general sense in the archaeology of Europe. Archived 2007-01-07 at the Wayback Machine However, the Final Neolithic also tends to refer to specific cultures. With reference to the Aegean, it means Late Neolithic Ib - II Archived 2006-05-25 at the Wayback Machine, during which painted ware was replaced by coarse ware in the Cyclades; on Crete, it means the Neolithic before EM I, which features coarse wares. In a general sense, all EM might have been Final Neolithic, as bronze materials do not start until the MM period. It is not, however, used in that sense with reference to Crete.

- Hayden, Barbara J. (2003). "The Final Neolithic-Early Minoan I/IIA Settlement History of the Vrokastro Area, Mirabello, Eastern Crete" (PDF). Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry. MAA. 3 (1): 31–44. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2011. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- Hutchinson, Chapter 6

- Pyrgos I-IV, EM I through LM I, has been defined.

- Examples 1, Examples 2.

- http://www.minoancrete.com/vasiliki.htm

- Willetts, Chapter 4

- Prior to the introduction of the wheel turn-table disks were used, such as were discovered in Myrtos I from EM times. The larger pots continued to be made this way.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2007. Knossos fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian

- T., Neer, Richard (2012). Greek art and archaeology : a new history, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. New York: Thames & Hudson Inc. p. 30. ISBN 9780500288771. OCLC 745332893.

- T., Neer, Richard (2012). Greek art and archaeology : a new history, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. New York. ISBN 9780500288771. OCLC 745332893.

- T., Neer, Richard (2012). Greek art and archaeology : a new history, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. New York. ISBN 9780500288771. OCLC 745332893.

- Neer, Richard (2012). Greek Art and Archeology. New York, New York USA: Thames and Hudson Inc. p. 36.

- Evans' term, after the Palace Period

- Knappet, Carl, in Cappel, 329-334

- Volume II, Page 634, Figure 398

- Documents in Mycenaean Greek Page 326.

- The ideograms vary somewhat. A link to the unicode standard is given.

- Only names on Cretan tablets are given.

- Most of these vessel types can be found in Betancourt's Cooking Vessels from Minoan Kommos: A Preliminary Report Archived 2013-11-04 at the Wayback Machine. The dates are MM and LM, which shows that the forms of the ideograms were long-standing.

- http://www.hieronymus.us.com/latinweb/Graeca/LinearB_Glossary.htm

- Best, Jan G. P.; Woudhuizen, Fred C. (1989). Lost Languages from the Mediterranean. ISBN 9004089349.

- Ventris wrote a letter Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine to Bennett concerning this reconstruction.

- Possibly *aukw-, but the origin of the p instead of a reflex of kW is troubling. For a detailed linguistic presentation see Brent Vine,

References

- Betancourt, Philip P. 1985. The History of Minoan pottery Princeton University Press. A handbook.

- Cappel, Sarah et al., eds., Minoan Archaeology: Perspectives for the 21st Century, 2015, Presses universitaires de Louvain, ISBN 2875583948, 9782875583949

- Hutchinson, Prehistoric Crete, many editions hardcover and softcover

- Matz, Friedrich, The Art of Crete and Early Greece, Crown, 1962

- Mackenzie, Donald A., Crete & Pre-Hellenic, Senate, 1995, ISBN 1-85958-090-4

- "Oxford", The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean, Eric H. Cline (ed.), 2012, Oxford UP, ISBN 9780199873609, google books

- Palmer, L. A., Mycenaeans and Minoans, multiple editions

- Preziosi, Donald and Louise A. Hitchcock 1999 Aegean Art and Architecture ISBN 0-19-284208-0

- Platon, Nicolas, Crete (translated from the Greek), Archaeologia Mundi series, Frederick Muller Limited, London, 1966

- Traunmueller, Sebastian, "Pots and Potters", in Cappel, google books

- Willetts, The Civilization of Ancient Crete, Barnes & Noble, 1976, ISBN 1-56619-749-X

- Yakubovich, Ilya, Sociolinguistics of the Luvian Language, Brill, 2010, ISBN 978-90-04-17791-8

| Library resources about Minoan pottery |

Further reading

- Betancourt, Philip P. 2007. Introduction to Aegean Art. Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press.

- Boardman, John. 2001. The History of Greek Vases: Potters, Painters, Pictures. New York: Thames & Hudson.

- MacGillivray, J.A. 1998. Knossos: Pottery Groups of the Old Palace Period BSA Studies 5. (British School at Athens) ISBN 0-904887-32-4 Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2002

- Preziosi, Donald, and Louise A. Hitchcock. 1999. Aegean Art and Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walberg, Gisela. 1986. Tradition and Innovation. Essays in Minoan Art (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp Von Zabern)

- Dartmouth College: Bibliography (see Pottery)

- Edey, Maitland A., Lost World of the Aegean, Time-Life Books, 1975

External links

- Dartmouth College: Prehistorical Archaeology of the Aegean website:

- Doumas Kristos' description of local pottery and Cretan imports from the excavations at Akrothiri (Santorini) (in English)

- GiselaWalberg finds little influence between Minoan vase-paintings and glyptic motifs (in English)

- Material and Techniques of the Minoan Ceramics of Thera and Crete, Thera Foundation

- Victor Bryant, Web Tutorial for Potters, under Crete & Mycenae

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Minoan pottery. |