Hagia Triada

Hagia Triada (also Ayia Triada, Agia Triada, Agia Trias, Greek: [aˈʝia triˈaða] — Holy Trinity) is the archaeological site of an ancient Minoan settlement.[1] Hagia Triada is situated on the western end of a prominent coastal ridge, with Phaistos at the eastern end and the Mesara Plain below.[2]

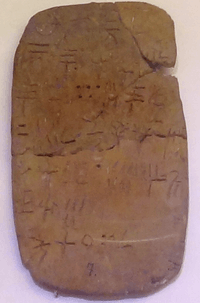

Hagia Triada has yielded more Linear A tablets than any other Minoan site. Important finds include the Hagia Triada sarcophagus, the Chieftain's Cup, the Boxer Vase, and the Harvester Vase.

Geography

Hagia Triada is in south central Crete, 30–40 meters above sea level. It lies four kilometers west of Phaistos, which is situated at the western end of the Mesara Plain. The site was not a Minoan palace but an upscale town and possibly a royal villa. After the catastrophe of 1450 BC, when the Mycenaeans attacked Crete and destroyed many Minoan settlements,[3] the town was rebuilt and remained inhabited until the 2nd century BC. Later, a Roman villa was built at the site. Nearby are two chapels: Hagia Triada in the deserted village and Hagios Georgios, built during the Venetian period.

Archaeology

Hagia Triada, as was nearby Phaistos, was excavated from 1900 to 1908 by a group from Italian Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene, directed by Federico Halbherr and Luigi Pernier. The site includes a town and a miniature "palace", an ancient drainage system servicing both, and Early Minoan tholos tombs. The settlement was in use, in various forms, from Early Minoan I until the fires of Late Minoan IB.

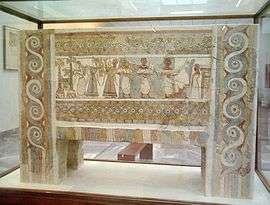

Archaeologists unearthed a sarcophagus painted with illuminating scenes from Cretan life.[4] It is the only limestone sarcophagus of its era discovered to date and the only sarcophagus with a series of narrative scenes of Minoan funerary ritual. However, it is possible that the Minoan religious beliefs were mixed with the beliefs of the Myceneans, who captured the island in the 14th century BC. It was originally used for the burial of a prince.

In the center of one of the long sides of the sarcophagus is the scene of a bull sacrifice. On the left of the second long side, a woman who is wearing a crown is carrying two vessels. By her side, a man dressed in a long robe is playing a seven-stringed lyre. This is the earliest known picture of the classical-Greek lyre.

In front of them, another woman is emptying the contents of a vessel—perhaps the blood of the sacrificed bull—into a second vessel, possibly as an invocation to the soul of the deceased.[5] It seems that the blood of the bull was used for the regeneration of the reappearing dead. This scene is reminiscent of a description of Homer, where the dead needed blood.[6] On the left, three men holding animals and a boat are approaching a male figure without limbs; he presumably represents the dead man receiving gifts. The boat is offered for his journey to the next world .[7] According to a Minoan belief, beyond the sea, there was the island of the happy dead Elysion, where the departed souls could have a different but happier existence. Rhadamanthys was the judge of the Elysion, and this idea probably predates some later Orphic beliefs.[6]

It seems that, in Crete, some festivals corresponded to later Greek festivals.[8] An agrarian procession is depicted on the "Harvesters' Vase", or "Vase of the Winnowers", which was found in Hagia Triada. The vase is dated from the last phase of the neopalatial period (LM II). Men are walking in twos with rods on their shoulders. The leader is dressed in a priestly robe with a fringe and is carrying a stick. A group of musicians accompany with song, and one of them holds the Egyptian sistrum.[9][10]

See also

- Asterousia Mountains

- Kalyvia

- Kommos

- Psiloriti Range

References

- Ian Swindale, Ayia Triada, retrieved 12 May 2013

- C.Michael Hogan, Phaistos Fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian (2007)

- "Mycenaens". www.historycentral.com. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Crete: The Archaeological Site of Agia Triada

- J.A.Sakellarakis, "Herakleion Museum. Illustrated guide to the Museum" pp. 113,114. Ekdotike Athinon. Athens 1987

- F.Schachermeyer (1972), Die Minoische Kultur des alten Kreta. Kohlhammer Verlag Stuttgart, p. 172, 185

- J.A.Sakellarakis, "Herakleion Museum. Illustrated guide to the Museum" p. 114. Ekdotike Athinon. Athens 1987

- Walter Burkert (1985), Greek religion, p. 42

- J.A.Sakellarakis, "Herakleion Museum. Illustrated guide to the Museum" p. 64. Ekdotike Athinon. Athens 1987

- F.Schachermeyer (1967) p. 144