Michael Herrick

Michael Herrick DFC* (5 May 1921 – 16 June 1944) was a New Zealand flying ace of the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War. He was credited with the destruction of eight enemy aircraft.

Michael Herrick | |

|---|---|

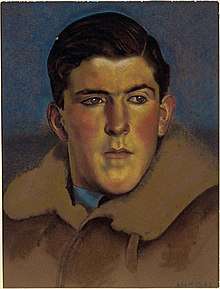

A portrait of Michael Herrick, painted by Eric Kennington in 1941 | |

| Born | 5 May 1921 Hastings, New Zealand |

| Died | 16 June 1944 (aged 23) Denmark |

| Allegiance | New Zealand |

| Service/ | Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1939–1944 † |

| Rank | Squadron Leader |

| Commands held | No. 15 Squadron RNZAF |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards | Distinguished Flying Cross & bar Air Medal (United States) |

Born in Hastings, New Zealand, Herrick joined the RAF in 1939. He flew Bristol Blenheims on night operations with No. 25 Squadron during the Battle of Britain, destroying three German bombers. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his achievements during the battle. In late 1941, having shot down five enemy aircraft, he was sent to New Zealand on secondment to the Royal New Zealand Air Force to take command of its newly formed No. 15 Squadron. With the squadron he flew two operational tours in the Pacific, including several missions around Guadalcanal. In 1944, having been awarded a bar to his DFC, he returned to England to resume service with the RAF. He joined No. 305 Polish Bomber Squadron, which operated the de Havilland Mosquito fighter-bomber, as one of its flight commanders. He was killed during a daylight raid on a German airfield at Aalborg in Denmark. In recognition of his services in the Pacific, he was posthumously awarded the United States Air Medal.

Early life

Michael James Herrick was born in Hastings in New Zealand on 5 May 1921, one of five boys of Edward Herrick and his wife, Ethne Rose née Smith.[1][2][3] He was educated at Hurworth School in Wanganui, before going onto Wanganui Collegiate School. While still at school, he took flying lessons and soon gained his pilot's licence. In 1938, he gained a cadetship for the Royal Air Force (RAF). This involved attending its college at Cranwell, and he travelled to England the following year to commence his training.[4]

Second World War

The outbreak of the Second World War forced Herrick's cadetship, originally scheduled to run for two years, to be consolidated and he gained his wings in early 1940.[4] Commissioned as a pilot officer in March,[5] he was posted to No. 25 Squadron which was stationed at North Weald and operated Bristol Blenheims.[4] The squadron flew covering patrols for the ships evacuating the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk. In June it began operating from Martlesham Heath, flying convoy patrols and undertaking night operations.[6]

Battle of Britain

Although its aircraft had been intended for light bombing, No. 25 Squadron was in the process of converting to a night fighting role and the Blenheims were equipped with airborne radar.[7] This switch to a night fighting role coincided with an increase in nightly bombing raids mounted by the Germans.[8] On the night of 5 September, despite his aircraft's radar set malfunctioning, Herrick spotted a Heinkel He 111 bomber caught in search lights and shot it down. Within minutes he repeated the feat, destroying a Dornier Do 17 bomber and exhausting his ammunition.[7] For his exploit, he was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). The published citation read:

During an interception patrol on the night of 4th September, 1940. Pilot Officer Herrick spotted two enemy aircraft and destroyed them both. In his attack against the second aircraft he succeeded in closing to within 30 yards and it fell in pieces under his fire.

— London Gazette, No. 34951, 24 September 1940.[9]

On 14 September, while flying a patrol north of London, he was directed by his radar to another Heinkel He 111. Climbing up behind the bomber he opened fire, prompting its crew to jettison its bombload. As the German aircraft went down out of control and exploded but not before its rear gunner caused minor damage to Herrick's aircraft.[7] He had accounted for three of the four German aircraft destroyed by Fighter Command on night operations during September.[8] No. 25 Squadron shifted north in November, flying from Wittering and covering the Midlands region. It began converting to Bristol Beaufighters[6] and by mid-1941 Herrick, now holding the rank of flying officer,[10] had destroyed a total of five German aircraft; his fifth, a Junkers Ju 88, had been shot down in June 1941.[11]

Secondment

In October 1941, Herrick was seconded to the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF)[6] and by the end of the year was back in the country of his birth. He spent a period of time as an instructor at the No. 2 Flying Training School at Woodbourne and then Ohakea before being posted to the RNZAF's No. 15 Squadron in June 1942.[1] The squadron had just been formed and, based at Whenuapai, was training with P-40 Kittyhawks.[12]

After a few months it was sent to Tonga, where it began operating P40s that had been recently used by the United States Army Air Force's No. 68 Pursuit Squadron, with responsibility for the air defence of the island.[13] In February 1943, the squadron moved to Espiritu Santo, the main island of Vanuatu, assuming a similar defence role there for a few weeks before, in April, being dispatched to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. Its role there was to carry out local patrols, fly as escorts for bombers, and provide cover for American shipping convoys. By this time Herrick was commander of the squadron; its original commanding officer had been killed in a flying accident.[1][14] The squadron's initial encounter with the enemy took place on 6 May; while escorting a Lockheed Hudson, Herrick and his wingman shared in the destruction of a Japanese float-plane.[15] This is acknowledged to be the first enemy aircraft shot down in the Pacific by fighters of the RNZAF.[1] A few days later he took part in an escort mission, leading a flight of eight P-40s accompanying light bombers attacking Japanese destroyers and strafing landing craft.[15] On 7 June, he was involved in a large dogfight that took place when a force of over 100 Allied fighters, including twelve P-40s from No. 15 Squadron, encountered nearly around 50 Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zeroes near the Russell Islands. On this occasion, Herrick shot down a Zero.[16][17]

In late June, No. 15 Squadron completed its first operational tour and returned to New Zealand for a rest. It was back in Guadalcanal to commence its second tour in September, again flying as escorts for bombing missions and covering convoys. On 1 October, Herrick shared in the destruction of an Aichi D3A "Val" dive bomber that was attacking a convoy transporting troops of the 3rd New Zealand Division to Vella Lavella. Herrick's kill was one of seven Japanese aircraft shot down by the squadron that day.[16][18] In late October, No. 15 Squadron moved to Ondonga in New Georgia;[19] it was to support operations against the Treasury Islands and Bougainville.[20]

On 27 October, during the landings at the Treasury Islands by New Zealand infantry and supporting troops, the squadron flew covering missions throughout the day. In doing so, they intercepted a force of 80 Japanese aircraft attempting to attack barges landing supplies and shot down four fighters, with Herrick accounting for one of them, a Zero.[16][21] The squadron also flew missions protecting the beachhead on Bougainville through out November. On one of these missions, Herrick was wounded in the foot during an attack on Japanese defensive positions. This would be his final sortie for he handed over command of the squadron and left to return to New Zealand.[16][22] In recognition of his services in the Solomons, Herrick was awarded a bar to his DFC; this was gazetted in February 1944.[23]

Return to the RAF

Herrick's stay in New Zealand was brief for his secondment to the RNZAF ended in December 1943 and the following month he embarked for England, via Canada, travelling on a troopship taking RNZAF personnel to Edmonton for flight training. Resuming his service with the RAF, he was sent to No. 305 Polish Bomber Squadron, where he took command of one of its flights.[24]

At the time he joined the squadron, it operated de Havilland Mosquito fighter-bombers on nighttime missions to mainland Europe, targeting enemy airfields and launching sites for V-1 rockets, but by the middle of the year it was also flying daytime operations. On 16 June 1944, Herrick and his Polish navigator flew a mission during the day to German-occupied Denmark, targeting a Luftwaffe airfield at Aalborg. They were accompanied by Wing Commander John Braham in his own Mosquito, flying as a pair until Braham separated to pursue his target in Copenhagen. As Herrick approached the Jutland coast, his Mosquito was attacked by a Focke Wulf Fw 190 flown by Leutnant Robert Spreckels. Although Herrick and his navigator bailed out when their aircraft was shot down, they were too low for their parachutes to open and were killed. Herrick landed in the sea and his body washed ashore two weeks later. Spreckels later shot down Braham, who became a prisoner of war. Interrogated by Spreckels, he was reportedly advised that Herrick had made a good account of himself before being shot down.[1][24]

Herrick is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission's section of the Frederikshavn Cemetery in Denmark.[2] The month after his death, it was announced that he was to be awarded the United States Air Medal, in acknowledgement of his services in the Pacific; the medal was presented to his parents in a ceremony in Wellington in June 1945 by Captain Lloyd Gray, the naval attache at the United States Embassy. The citation specifically noted his exploits in the Solomon Islands area during the period of May to June 1943.[25][26] Two of his brothers also served in the RAF; both died on flying operations in the early years of the war.[1]

Notes

- Phipps, Gareth. "Michael Herrick Biography". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Casualty Record: Herrick, Michael James". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- "Herrick, Edward Jasper". Hawke's Bay Digital Archives Trust. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Wynn 1981, p. 197.

- "No. 34841". The London Gazette. 19 March 1940. p. 1637.

- Wynn 1981, p. 198.

- Claasen 2012, pp. 153–154.

- Thompson 1953, p. 90.

- "No. 34951". The London Gazette. 29 September 1940. p. 5655.

- "No. 35158". The London Gazette. 9 May 1941. p. 2671.

- Thompson 1953, p. 134.

- Ross 1955, p. 110.

- Ross 1955, pp. 139–140.

- Ross 1955, pp. 180–181.

- Ross 1955, pp. 181–182.

- Wynn 1981, p. 200.

- Ross 1955, pp. 184–185.

- Ross 1955, p. 197.

- Ross 1955, p. 200.

- Ross 1955, p. 204.

- Ross 1955, p. 205.

- Ross 1955, p. 212.

- "No. 36392". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 February 1944. p. 909.

- Wynn 1981, p. 201.

- "Great Record - Hastings Family: M. J. Herrick's Award". Gisborne Herald. 15 June 1945. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- Wynn 1981, p. 202.

References

- Claasen, Adam (2012). Dogfight: The Battle of Britain. Anzac Battle Series. Auckland, New Zealand: Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921497-28-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, J. M. S. (1955). Royal New Zealand Air Force. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch. OCLC 912824475.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, H. L. (1953). New Zealanders with the Royal Air Force. Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45. I. Wellington: War History Branch. OCLC 270919916.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wynn, Kenneth G. (1981). A Clasp for 'The Few': New Zealanders with the Battle of Britain Clasp. Auckland, New Zealand: Kenneth G. Wynn. ISBN 0-86-465-0256.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)