Michael Franzese

Michael Franzese (born May 27, 1951) is an American former New York mobster and caporegime of the Colombo crime family, and son of former underboss John Franzese. Franzese was enrolled in a pre-med program at Hofstra University, but dropped out to make money for his family after his father was sentenced to 50 years in prison for bank robbery in 1967. He eventually helped implement a scheme to defraud the federal government out of gasoline taxes in the early 1980s.

Michael Franzese | |

|---|---|

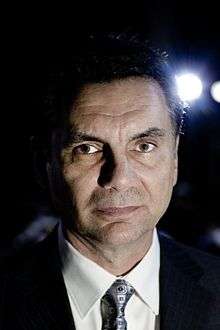

Franzese in 2009 | |

| Born | May 27, 1951 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | "The Yuppie Don" |

| Occupation | Mobster (former), motivational speaker, writer |

| Spouse(s) | Camille Garcia (second wife) |

| Children | 7 |

| Parent(s) | John Franzese Cristina Capobianco-Franzese |

| Relatives | John Franzese Jr. (brother) |

| Allegiance | Colombo crime family (former) |

| Conviction(s) | Racketeering conspiracy, tax conspiracy |

| Criminal penalty | 10 years' imprisonment and ordered to pay over $14 million in restitution (1986) |

By the age of 35, in 1986, Fortune Magazine listed Franzese as number 18 on its list of the "Fifty Most Wealthy and Powerful Mafia Bosses". Franzese had claimed that at the height of his career, he was making up to $8 million per week. In 1986, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison on conspiracy charges, released in 1989, rearrested in 1991 for a parole violation, and ultimately released in 1994. Soon after, he retired to California and is now a motivational speaker and writer.

Early life

Franzese was born on May 27, 1951, in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, to John "Sonny" Franzese, a Colombo crime family underboss, and Cristina Capobianco-Franzese, although Michael had initially questioned his actual biological father.[1] Franzese had initially believed that he had been adopted by John after his mother divorced Frank Grillo, who Franzese thought to be his biological father.[2] Michael claims he had gone by the name "Michael Grillo" until he was 18 years old.[3] However, it was later discovered that John, already married with three children, had gotten the 16-year-old Capobianco, a cigarette girl at the Stork Club in Manhattan, pregnant with Michael, so Capobianco married Grillo to avoid having a scandal surrounding having a child out of wedlock. After the mob allowed John to divorce his first wife, Grillo disappeared, and he married Capobianco.[2]

Franzese later moved to Long Island. After finishing high school, Franzese entered a pre-med program at Hofstra University in 1969; his father originally did not want him to be involved in organized crime.[4] However, in 1971, Franzese decided to drop out of college to help his family earn money when his father was sentenced to 50 years in prison for bank robbery in 1967.[5]

Franzese became acquainted with his father's friends such as Joseph Colombo, and later became inducted as a made man on Halloween night 1975.[6] Franzese took the blood oath alongside friend Jimmy Angelino, Joseph Peraino Jr., Salvatore Miciotta, Vito Guzzo Sr., and John Minerva — all of whom died violently over the next 20 years.[7][8][9][10][11] Although Franzese recounts this ceremony had taken place in 1975, the membership books reportedly were not reopened until 1976 (they had been closed since 1957).[12]

Franzese was briefly mentored by Colombo soldier Joseph "Joe-Joe" Vitacco (1927–1980).[13][14] During the late 1970s, Franzese met with Gambino crime family boss John Gotti, who was then a soldier. Angelo Ruggiero was also present. Franzese was contacted by a flea market owner who complained that his partner was using and selling drugs at the market in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. Franzese agreed to frighten him and become the new partner. Franzese sent Colombo soldier-turned informant Anthony Sarivola and another member who remains unidentified.[15] Gotti however claimed that the scared-off partner was an associate of his. After several meetings, Franzese proposed to buy Gotti out. Gotti replied, "Buy me out? I buy you out," and handed over $70,000. Franzese later expressed admiration for Gotti, citing his strict gangster lifestyle and his overwhelming ego.[16]

In 1980, Franzese had become a caporegime of a crew of 300.[17][18]

Gasoline bootlegging

In 1980, Franzese was contacted by Lawrence Salvatore Iorizzo, who initially thought of a scheme to defraud the federal government out of gasoline taxes.[19] Iorizzo was being hassled by associates of another crime family and promised Franzese a percentage if he would defend and solve the issue. The pair set up 18 stock-bearer companies based in Panama. Once authorities suspected one company of fraudulent activity, Franzese would move onto the next company. Under law at the time in Panama, gasoline could be sold tax-free from one wholesale company to the next.[20] Iorizzo, who later turned informant and testified against Franzese, craved power. As a result of Iorizzo slapping around Shelly Levine over $270,000 debt, Franzese had to cut in Genovese family soldier Joseph "Joe Glitz" Galizia into his operation. He had organized the Russian Mafia in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn and both organizations became partners, Franzese sold millions of gallons of gasoline.[21] The family would collect the state and federal taxes, but keep the money instead. At the same time, they were often selling the gas at lower prices than at legitimate gas stations. In 1986, Fortune Magazine listed Franzese as number 18 on its list of the "Fifty Most Wealthy and Powerful Mafia Bosses".[22] Franzese had claimed that at the height of his career, he was making up to $8 million per week.[23] He bought a home in Delray Beach, Florida.[6]

Entertainment, sports management and other businesses

During the 1970s, he began to enter the world of legitimate business and by the mid 1980s Franzese had a stronghold on various businesses such as car dealerships, leasing companies, auto repair shops, restaurants, nightclubs, a contractor company, movie production and distribution companies, travel agencies and video stores.[24]

By 1980, Franzese was a partner with booking agent Norby Walters in his firm. Franzese's role was to intimidate existing and prospective clients. In 1981, Franzese successfully extorted a role for Walters in the US tour by singer Michael Jackson and his brothers. In 1982, the manager for singer Dionne Warwick wanted to drop Walters as an agent; Franzese met with the manager and persuaded him to keep Walters.[25]

In 1983, the FBI launched an investigation into boxing promoter Don King's organized crime connections and targeted Franzese to introduce an FBI undercover agent, using the alias Victor Quintana, to King. Franzese, who had never met King, was introduced to him by civil rights leader Al Sharpton. Franzese first met Sharpton through Genovese crime family mobster, Daniel Pagano.[26] Sharpton later helped Franzese with muscle as he targeted the security guard unions in Atlantic City. Quintana was to give the impression that he was buying his way into the boxing world in order for King to reveal his criminal associations, however the investigation subsequently collapsed after Quintana failed to follow through with several hundred thousand dollars.[27]

In 1985, Walters set up a sports management agency with Franzese as a silent partner. At a meeting he agreed to hand over $50,000 in return for a 25 percent interest from the sports agency.[28]

Indictment and prison

In April 1985, Franzese was acquitted of racketeering charges.[29] In December 1985, Franzese was one of nine people indicted on 14 counts of racketeering, counterfeiting and extortion from the gasoline bootlegging racket, and on March 21, 1986, pleaded guilty to one count of racketeering conspiracy and one count of tax conspiracy.[19][25][30] He was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison and ordered to pay over $14 million in restitution, agreeing to sell his mansion in Old Brookville, New York and use proceeds from the 1986 film he produced, Knights of the City.[31][30] Franzese had met his future wife Camille Garcia while shooting the film in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, in 1984.[6][21]

In 1989, Franzese was released from prison on parole after serving 43 months.[31] On December 27, 1991, Franzese was sentenced in New York to four years in federal prison for violating the probation requirements from his 1989 release.[31] Franzese had been arrested in Los Angeles on a tax fraud accusation and was sent back to New York for the probation hearing.[31] In court, prosecutors complained that Franzese had only started paying the balance of his court-ordered restitution payments earlier that year.[31] Franzese was also later subpoenaed to testify at Walters' trial in 1989, as Walters had invoked his name to frighten college athletes into signing management contracts, including Maurice Douglass, allowing him to get a reduced sentence.[25][31] Prosecutors have said that Franzese was not considered by the government to be a federal cooperating witness.[31] While imprisoned in 1991, Franzese became a born-again Christian after he was given a Bible by a prison guard.[32] He also spent time in solitary confinement.[21] He was ultimately released on November 7, 1994, retiring from the mob in 1995 by moving to California with his wife and children; the relocation was also a result of receiving multiple death threats and contracts on his life, including one approved by his father.[18][14][21]

Motivational speaker and writer

In 1992, Franzese co-authored his first book, an autobiography, Quitting the Mob.[33] In the book, Franzese discusses his criminal activities, life with his father, and meeting his second wife Camille Garcia.

Since his release in 1994, Franzese has publicly denounced the life of organized crime, and became a motivational speaker for youth, at schools, and other venues.[34] He also frequently speaks at Christian conferences and churches, including helping the Willow Creek Community Church, in November 2016, to give each of the 70,000 inmates in the state of Illinois a Christmas package. Franzese also speaks at prisons throughout the world, such as Pentonville Prison in England. In 2016, he vowed to help Christian refugees fleeing the Middle East.[35]

Franzese has also been interviewed on several radio, TV and online platforms. On July 23, 2002, while appearing on the HBO television program "Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel", Franzese claimed that during the 1970s and 1980s, he persuaded New York Yankees players who owed money to Colombo loansharks to fix baseball games for betting purposes. The Yankees organization immediately denied Franzese's accusations.[14]

In 2003, Franzese published Blood Covenant, an updated and expanded life story.[36] He appeared in the 2013 Inside the American Mob, a National Geographic documentary.[37]

As of 2017, Franzese lives in Anaheim, California and is the father of seven children. As of 2020, he is the author of six books: Quitting the Mob (1992), Blood Covenant (2003), The Good, the Bad and the Forgiven (2009), I'll Make You an Offer You Can't Refuse (2011), From the Godfather to God the Father (2014), and Blood Covenant: The Story of the "Mafia Prince" Who Publicly Quit the Mob and Lived (2018).[38]

In popular culture

Franzese was portrayed by Joseph Bono in the Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas (1990).[39]

In April 2013, a documentary called The Definitive Guide To The Mob was released by Lionsgate, with Franzese as commentator.[40]

In June 2013, the National Geographic Channel released a six-part series called Inside the American Mob, in which, as among other story lines, Franzese's climb up the ranks in the Colombo family is chronicled.[41]

His biopic, God the father, was released in theaters and cinemas across the United States on October 31, 2014.[42]

In March 2015, he appeared in a two-part documentary on the American Mafia with television presenter and reporter Trevor McDonald.[43][44] He spoke about his wealth, but also the impact of being a member of the Colombo crime family had on his family, and that was why he turned away from organized crime.[45][46][47]

Franzese hosted a stage musical, A Mob Story, at the Plaza Hotel & Casino in Las Vegas. The show opened in October 2018 and was created and directed by Jeff Kutash.[48]

In July 2020, he appeared in the Fear City: New York vs The Mafia Netflix docuseries.[49]

References

- "A Godfather Betrayed by His Namesake, Part II". nysun.com. May 17, 2007. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "Making a killing". smh.com.au. July 10, 2015. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Franzese, Michael (2009-10-28). Blood Covenant. ISBN 9781603741958.

- "Penn State Forum Speaker Series Michael Franzese "Life Choices, Life Stories"" (PDF). psu.edu. September 12, 2008.

- "At 100, mob underboss Sonny Franzese gets out of federal prison". Newsday. Archived from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "MEMORIES OF THE MOB, INSIDE AND OUT". sun-sentinel.com. May 24, 1992. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- "TWO SLAIN AND ONE HURT IN A MOB-STYLE SHOOTING". Les Ledbetter. The New York Times. 5 January 1982. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "HOOD'S TALE UNDERLINED IN LEAD". William K. Rashbaum. New York Daily News. 16 November 1997. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "A mobster's trail of bodies". David Goldiner. New York Daily News. 29 September 2000. Archived from the original on 20 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- COLOMBO ORGANIZED CRIME FAMILY ACTING BOSS, UNDERBOSS, AND TEN OTHER MEMBERS AND ASSOCIATES INDICTED" Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine Department of Justice press release June 4, 2008

- Secret, Mosi (March 20, 2014). "After Serving Six Years, Mobster Receives His Sentence". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Five Mafia Families Open Rosters to New Members". nytimes.com. March 21, 1976. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "The Born-Again Don". Vanity. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Schwarz, Alan (July 12, 2001). "BASEBALL; From Captain to Coach: Ex-Goodfella's New Life". New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- "Even the trial of federal witness Anthony Sarivola bears secrets". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Franzese, Michael (2009-10-28). Blood Covenant. ISBN 9781603741958.

- "Former Colombo family capo to visit Mob Museum and tell how he left the mafia but lived to talk about it". lasvegassun.com. October 30, 2007. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- "Special Report: Michael Franzese talks about quitting the mob". KFVS. 2010. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- "9 LINKED TO MAFIA ARE ACCUSED OF BILKING LEGITIMATE BUSINESSES". nytimes.com. December 20, 1985. Archived from the original on 2015-05-24.

- "ON THE LAM with an UBER-MOBSTER". The New Yorker. November 14, 1994. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Wilson, Jeremy (2009-06-12). "Former mafia boss Michael Franzese sounds warning over match-fixing". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Roy Rowan; Andrew Kupfer (1986-11-10). "The 50 Biggest Mafia Bosses". CNN Money. Fortune Magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-03-11. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- "Mob boss calls a stock bubble". cnbc.com. August 20, 2014. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- "Former mobster Michael Franzese is trying to do good in the world as a motivational speaker and author". Business Enquirer. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Fiffer, Steve (March 15, 1989). "Crime Figure Testifies to Link With Sports Agent". New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- "Sports of The Times; Is Don King's Asbestos Tuxedo Turning Toxic at Last?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Sharpton Says F.B.I. Tape Distorts Truth". The New York Times. July 24, 2002. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Fiffer, Steve; Times, Special to The New York (1989-03-15). "Crime Figure Testifies to Link With Sports Agent". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "NEW BREED SAID TO EMERGE IN ORGANIZED CRIME". nytimes.com. December 20, 1985. Archived from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- "FRANZESE ENTERS A PLEA OF GUILTY TO RACKETEERING". nytimes.com. March 22, 1986. Archived from the original on 2015-05-24.

- Lubasch, Arnold H (December 28, 1991). "Mobster Sentenced in Probation Violation". New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- "Former mobster: 'God changed my heart'". chicagotribune.com. September 10, 2007. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- Franzese, Michael; Matera, Dary (1992). Quitting the Mob. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-88368-867-0.

- Khan, Saher (March 10, 2017). "20 years a mobster, Michael Franzese now inspires gangsters to turn their lives around". WGN-TV. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- "In Chicago, former mob boss Michael Franzese vows to help clean up Chicago, organize churches to fight Christian genocide in Syria". PR News Channel. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- Franzese, Michael (2003). Blood Covenant. Whitaker House. ISBN 978-0-88368-867-0.

- "Joe Pistone talks about Donnie Brasco on 'Inside the American Mob'". Usedview. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "Michael Franzese". Amazon. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Former mobster Michael Franzese is trying to do good in the world as a motivational speaker and author". The Straits Times. 2014-07-21. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "The definitive guide to the mob". Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

Originally broadcast on television in 2013.

- "Inside The American Mob". natgeotv.com. Archived from the original on 2019-10-06. Retrieved 2019-10-06.

- "God the Father". IMDB. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

Release Dates USA 31 October 2014

- "The Mafia with Trevor McDonald". Archived from the original on 2017-04-21. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- "The Mafia with Trevor McDonald Episode 1". Archived from the original on 2017-04-26. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- "The Mafia with Trevor McDonald, ITV, review: 'surreal' – Telegraph". Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- "Trevor McDonald Meets the Mafia and exposes shocking tales – Daily Post". Archived from the original on 2017-04-26. Retrieved 2017-04-25.

- "The Mafia with Trevor McDonald, review: Nice guy Trevor just isn't cut out for the mean streets | The Independent". Archived from the original on 2017-05-19. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- "The ambitious, original 'A Mob Story' is worth a visit to the Plaza". lasvegassun.com. October 24, 2018. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Fienberg, Daniel (July 21, 2020). "'Fear City: New York vs. the Mafia': TV Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved July 22, 2020.