Mbalax

Mbalax (or Mbalakh) is the national popular dance music of Senegal and the Gambia. Mbalax has its sacred origins in the Serer people's[1][2] ultra-religious, ultra-conservative njuup music tradition—and their sacred ndut rite ceremonies.[1][2] By the 1970s, it became a fusion with other popular music from the African diaspora, the West, and afropop such as jazz, soul, Latin, Congolese rumba, and rock blended with sabar, the traditional drumming and dance music of the Wolof of Senegal. The genre's name derived from accompanying rhythms used in sabar called mbalax.

| Mbalax | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | Serer music tradition of Njuup and the sacred Ndut rites[1][2] Soukous Wolof music Congolese pop |

| Cultural origins | Early 1970s Senegal and the Gambia |

History and influence

The traditional form of mbalax originated from the sabar, a Wolof genre that historically fused musical and cultural practices from different ethnic groups such as the Njuup, a religious Serer music. The popular dance form of mbalax developed in urban Senegal in the early 1970s. Like many other francophone West African countries the Senegalese popular music scene was partially influenced by soul, blues, jazz, R&B, and rock from the United States, varieté from France, Congolese rumba, and Latin pop from the Caribbean and New York (e.g., pachanga, son, charanga, salsa, and Latin jazz).In this mix of African diasporic sounds Senegalese fans and musicians wanted their own urban popular dance music so they began singing in Wolof (Senegal's lingua franca) instead of French, and incorporated rhythms of the indigenous sabar drum (see Mangin[3]). Dancers began using moves associated with the sabar, and tipping the singers as if they were traditional griots.

Among the bands that played this new style, Etoile de Dakar (starring Youssou N'Dour and El Hadji Faye), and Raam Daan (starring Thione Seck), Xalam II, and Super Diamono. Since becoming popular, both Mbalax and its associated dance have spread to other regions such as Mali, Mauritania, Ivory Coast and France. This dissemination has come about through radio, audio cassettes and televised video clips.

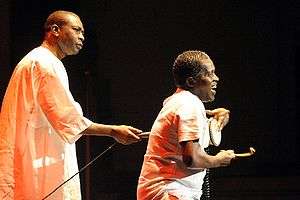

Mbalax instrumentation includes keyboards, synths and other electronic production methods. However, it is the Nder (lead drum), the Sabar (rhythm drum), and the Tama (talking drum) percussion, and widely influenced African and Arabic vocalistic stylings that continue to make Mbalax one of the most distinctive forms of dance music in west Africa and the diaspora. Jazz, Funk, Latin (especially Cuban) and Congolese pop music influenced the early sounds of Mbalax, today it is also influenced by RnB, Hip-Hop, Coupé-Décalé, Zouk and other modern Caribbean, Latin, and African pop musics. Mbalax artists frequently collaborate with artists from other genres, such as Viviane Ndour's work with Zouk star Philip Monteiro and French/Malian rap star Mokobé. Perhaps the most well known collaboration of all was Youssou Ndour's huge hit with Neneh Cherry; 'Seven Seconds'.

Mbalax dance

Mbalax Dancing is popular in nightclubs and social gatherings as well as religious and life cycle events such as: weddings, birthdays, and naming ceremonies.

The basic mbalax dancing involves pelvic gyrations and knee movements, but new movements arise as well, often associated with popular songs. [4] Patricia Tang describes some of the new movements:

"Examples of such dances are the ventilateur ('electric fan', which describes the motion of the buttocks swirling suggestively); xaj bi ('the dog', in which a dancer lifts his/her leg in imitation of a dog); moulaye chigin (which involves pelvic and knee movements that perfectly match the sabar breaks); and more recently, the jelkati (a dance in which the upper arms, bent at the elbows, move in parallel motion from left to right). All of these dance crazes are closely tied to sabar breaks, and some (such as tawran tej) are even named for the vocal mnemonics of the sabar rhythm they accompany."[4]

Music and instrumentation

Senegalese songs are usually unwritten, and certain instruments or musical styles are reserved for specific genders or age groups. In the past, only griots could perform music. Their traditional role was transmitting oral history, genealogies and social rankings, diplomacy, and storytelling. Today, griots continue to participate in naming ceremonies, weddings, and funerals.

Music is performed using instruments such as drums, balafon, riti, Tama (talking drum), sabar drum. In the 1970s Western instruments and equipment such as the flute, electric guitar, piano, violin, trumpet and synthesizer have been incorporated into the music, to accompany the dance. In addition to the instrumentation, humming, chanting and singing (in either Wolof, French or English) are used to accompany the music that the dance is done to. The lyrics of mbalax songs address social, religious, familial, or moral issues.

According to author Patricia Tang:

"The rhythmic foundation and primary identifiable feature of modern mbalax is the sabar...in Wolof gewel percussionist parlance, mbalax literally means 'accompaniment'. Within a sabar ensemble, different drums play different roles, and mbalax refers to the accompaniment parts played by the mbeng-mbeng. However, the mbalax part varies rhythmically from one dance to another.[5]

Artists

- Musa Ngum

- Youssou N'Dour

- Thione Seck et Raam Daan

- Omar Pène et Super Diamono

- Yusupha Ngum

- Pape Diouf

- Assane Ndiaye

- Abu Thioubalo

- Alioune Mbaye Nder

- Fatou Guewël et Le Group Sopiye

- Viviane N'Dour

- Assane Mboup

- Coumba Gawlo

- Fatou Laobé

- Kiné Lam Mame Bamba

- Adiouza

- Zale Seck

- Titi

- Waly Seck

- Ismaël Lô

References

- Sturman, Janet, The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture, SAGE Publications (2019), p. 1926 ISBN 9781483317748 (Retrieved 13 July 2019)

- Connolly, Sean, Senegal, Bradt Travel Guides (2009), p. 27, ISBN 9781784776206 (Retrieved 13 July 2019)

- Mangin, Timothy R. "Notes on Jazz in Senegal." Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies. Eds. O'Meally, Robert G., Brent Hayes Edwards and Farah Jasmine Griffin. New York City, Canada: Columbia University Press, 2004. 224-49. Print.

- Tang, Patricia (September 2007). Masters of the Sabar: Wolof Griot Percussionists of Senegal. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 159.

- Tang, Patricia (September 2007). Masters of the Sabar: Wolof Griot Percussionists of Senegal. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 155.