Magdalen Islands

The Magdalen Islands (French: Les Îles de la Madeleine [lez‿il də la madˈlɛn]) are a small archipelago in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence with a land area of 205.53 square kilometres (79.36 sq mi). Administratively, the islands are part of the Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine region in the Canadian province of Quebec, but geographically, they are closer to the Maritime provinces than to the Gaspé Peninsula, on the Quebec mainland.

The Magdalen Islands | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Gulf of Saint Lawrence |

| Coordinates | 47°26′54″N 61°45′08″W |

| Area | 205.53 km2 (79.36 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

Canada | |

| Province | Quebec |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 12,781 (2011) |

| Pop. density | 62.2/km2 (161.1/sq mi) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| • Summer (DST) |

|

| Area code(s) | 418 and 581 |

The islands form the territory equivalent to a regional county municipality (TE) and the census division (CD) of Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine. Their geographical code is 01.

The islands also form the urban agglomeration of Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine, which is divided into two municipalities: Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine (2011 census pop. 12,291), the central municipality, and Grosse-Île (pop. 490). Their mayors are Jonathan Lapierre and Rose Elmonde Clarke, respectively.

Geography

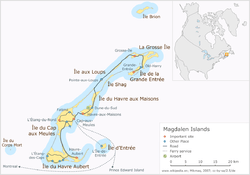

There are eight major islands: Amherst, Grande Entrée, Grindstone, Grosse-Île, House Harbour, Pointe-Aux-Loups, Entry Island, and Brion,[1][2] all except Brion being inhabited. There are several other tiny islands that are also considered to be part of the archipelago: Bird Rock (Rocher aux Oiseaux), Seal Island (Île aux Loups-marins), Île Paquet, and Rocher du Corps Mort.[3]

The interiors of the islands were once completely covered with pine forests.[2] An ancient salt dome underlies the archipelago.[1][4] The salt's inherent buoyancy forces the uplift of the overlying Permian red sandstone.

Nearby salt domes are believed to be sources of fossil fuels.[5] Rock salt is mined on the Islands.[6]

Erosion

Several news articles in 2019 pointed out that erosion of the coastline had already become a significant issue. Researchers have found that the amount has doubled since 2005, and was averaging half a meter per year. Recent events that added to the problem included a significant windstorm in November 2018 and the post-tropical storm Dorian that hit the islands in September 2019.[7]

A Washington Post report in late October 2019 also indicated that increasing temperatures have led to reduced ice cover over the years, leading to less protection from winter storms. "That ice has been disappearing ... [and the] sea-level rise, have caused the islands to crumble into the sea". [8]

Researchers have found that the rise in sea levels has been approximately double that of the global norm and that the sea ice is shrinking at approximately 12% per decade. A November 2019 Washington Post report provided these specifics about the effects of erosion:[9]

"Some parts of the shoreline have lost as much as 14 feet per year to the sea over the past decade. Key roads face perpetual risk of washing out. The hospital and the city hall sit alarmingly close to deteriorating cliffs. Rising waters threaten to contaminate aquifers used for drinking water ... Nearly a dozen homes on the islands have been relocated, and most everyone expects that number to grow."

The sole benefit has been the increase in lobster yields on the islands, at least double what was the norm in the past.

History

In 1534, the explorer Jacques Cartier was the first known European to visit the islands. However, Mi'kmaqs had been visiting the islands for hundreds of years, as part of a seasonal subsistence migration,[10] probably to harvest the abundant walrus population. A number of archaeological sites have been excavated on the archipelago.

The archipelago was named in 1663 by François Doublet (1619 or 1620 - approx. 1678), the seigneur of the island, after his wife, Madeleine Fontaine.[11]

In 1765, the islands were inhabited by 22 French-speaking Acadians and their families. They were working and hunting walruses for a British trader, Richard Gridley. Many inhabitants of the Magdalen Islands (Madelinots) still fly the Acadian flag and identify as both Acadian and Québécois.

The islands were administered as part of the British Colony of Newfoundland from 1763 to 1774, when they became part of Quebec by the Quebec Act.

Some of the islanders are descendants of survivors of the more than 400 shipwrecks on the islands. Some of the historic houses were built from wood that was from the shipwrecks.[12]

The islands have some of Quebec's oldest English-speaking settlements. Although most anglophones have long either assimilated with the francophone population or migrated elsewhere, English-speaking settlements are found at Old Harry, Grosse-Ile, and Entry Island.

The islands are known for a children's French camp. Activities include sand castle competitions and a night alone in the woods.

To improve the safety of ships, the government constructed lighthouses on the islands. They indicate navigable channels and have reduced the number of shipwrecks, but many old hulks are found on the beaches and under the waters.

Until the 20th century, the islands were completely isolated during the winter since the pack ice made the trip to the mainland impassable by boat. The islands had no means of communication with the mainland. An underwater cable was installed to enable communication by telegraph, but in winter 1910, the cable broke, and the islands were again isolated. Residents sent an urgent request for help to the mainland by writing letters and sealing them inside a molasses barrel, or puncheon, which they set adrift. It reached the shore on Cape Breton Island, where residents notified the government of the emergency. The government sent an icebreaker to bring aid.

Within a few years, the government constructed new wireless telegraph stations on the Magdalens to ensure that they had communications during the wintertime. The puncheon became famous as a symbol of survival, and every tourist shop sells replicas.

At one time, large walrus herds were found near the islands, but over-hunting had eliminated them by the late 18th century.

In the 21st century, the islands' beaches provide a habitat for the endangered piping plover and the roseate tern.

Demographics

Population

| Canada census – Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine, Quebec community profile | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2006 | ||

| Population: | 12,781 (-2.4% from 2006) | 13,091 (+2.1% from 2001) | |

| Land area: | 205.40 km2 (79.31 sq mi) | 205.40 km2 (79.31 sq mi) | |

| Population density: | 62.2/km2 (161/sq mi) | 63.7/km2 (165/sq mi) | |

| Median age: | 48.1 (M: 47.9, F: 48.4) | 44.5 (M: 44.1, F: 44.9) | |

| Total private dwellings: | 6,153 | 5,838 | |

| Median household income: | $52,267 | $47,914 | |

| References: 2011[13] 2006[14] earlier[15] | |||

|

|

|

Language

| Canada Census Mother Tongue - Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine, Quebec[16] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Total | French |

English |

French & English |

Other | |||||||||||||

| Year | Responses | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | Count | Trend | Pop % | |||||

2011 |

12,660 |

11,900 | 94.00% | 695 | 5.49% | 40 | 0.32% | 25 | 0.20% | |||||||||

2006 |

12,975 |

12,030 | 92.72% | 830 | 6.40% | 50 | 0.38% | 65 | 0.50% | |||||||||

2001 |

12,575 |

11,800 | 93.84% | 710 | 5.65% | 25 | 0.20% | 40 | 0.32% | |||||||||

1996 |

13,730 |

12,925 | n/a | 94.13% | 715 | n/a | 5.21% | 60 | n/a | 0.44% | 30 | n/a | 0.22% | |||||

Climate

The maritime climate of the Magdalen Islands is markedly different from that of the mainland. The huge water masses that circle the archipelago both temper the weather and create milder conditions in each season. On the islands, winter is mild, spring is cool, summer has a few heat waves, and fall is typically warm. The Magdalen Islands have the least annual frost in Québec. The warm breezes of summer persist well into September and sometimes early October.[17] However, under the Köppen climate classification its climate is humid continental because its winters average far below freezing by maritime standards. Seasonal lag is strong because of the freezing water and the time that it takes for the gulf to warm up again. Also, in winter, sea ice occasionally forms, impeding offshore communications and activities.[18][19]

The highest temperature ever recorded was 31.1 °C (88 °F) on 31 July 1949.[20] The lowest temperature ever recorded was −27.2 °C (−17 °F) on 14 February 1891.[20]

The Magdalen Islands have warmed 2.3 degrees Celsius since the late 19th century, twice the global average. As a result, the residents are facing a growing number of problems, as extreme climate change transforms the land and water around them. The sea ice that used to encase and protect the islands from most winter storms is shrinking at a rate of about 555 square miles annually. Parts of the shoreline have eroded into the sea at a rate as much as 14 feet per year over the decade of the 2010s. Important roads are at risk of washouts, and important infrastructure, including the hospital and city hall sit near deteriorating cliffs. Recently the sea has been rising at a rate of 7 mm per decade, threatening to contaminate freshwater aquifers.[21]

| Climate data for Îles-de-la-Madeleine Airport, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1890–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.3 (54.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.0 (53.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.9 (84.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

0.2 (32.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.4 (20.5) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

13.9 (57.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

5.0 (41.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −9.7 (14.5) |

−12 (10) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

5.6 (42.1) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−4.8 (23.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.5 (−15.7) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

−26.1 (−15.0) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−27.2 (−17.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 97.3 (3.83) |

74.3 (2.93) |

76.0 (2.99) |

73.7 (2.90) |

86.3 (3.40) |

76.3 (3.00) |

75.5 (2.97) |

84.7 (3.33) |

95.8 (3.77) |

94.1 (3.70) |

108.9 (4.29) |

94.3 (3.71) |

1,037.3 (40.84) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 37.1 (1.46) |

27.4 (1.08) |

39.0 (1.54) |

56.7 (2.23) |

82.0 (3.23) |

76.3 (3.00) |

75.5 (2.97) |

84.2 (3.31) |

95.8 (3.77) |

93.3 (3.67) |

91.6 (3.61) |

43.6 (1.72) |

802.6 (31.60) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 61.1 (24.1) |

47.5 (18.7) |

37.0 (14.6) |

17.0 (6.7) |

4.5 (1.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.7 (0.3) |

17.3 (6.8) |

51.7 (20.4) |

236.8 (93.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 22.2 | 16.6 | 16.8 | 14.0 | 14.5 | 12.4 | 13.1 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 17.4 | 19.1 | 21.4 | 193.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 5.6 | 4.3 | 7.3 | 10.6 | 14.1 | 12.3 | 13.1 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 17.2 | 14.1 | 7.2 | 131.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 20.2 | 14.4 | 12.3 | 6.1 | 0.95 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.61 | 7.8 | 17.9 | 80.2 |

| Source: Environment Canada[22][20][23] | |||||||||||||

Tourism

Tourism is a major industry on the islands, which have many kilometres of white sand beaches and steadily-eroding sandstone cliffs. Also, they are a destination for bicycle camping, sea kayaking, windsurfing, and kitesurfing. During the winter months, beginning in mid-February, ecotourists visit to observe newborn and young harp seal pups on the pack ice in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which surrounds the islands.

Industry

The island is home to Canadian Salt Company Seleine Mines, which produces road salt for use in Quebec, Atlantic Canada and the United States' eastern seaboard.[24] Opened in 1982, the salt mine and plant is located in Grosse-Île and extracts salt from an underground mine 30 metres (98 ft) below Grande-Entrée Lagoon. It produces 1 million tons of salt, and employs 200 people.

Although fishing is a traditional occupation, lobster have become a more lucrative local business. It was once common for lobstermen to haul in 15,000 pounds during a nine-week season that begins each spring, but now it is not unusual to bring home twice that amount, or more.[21] This may be due to climate change has warmed the surrounding waters to some extent, yielded increasing lobster harvests.

Transportation

The Coopérative de transport maritime et aérien (Groupe C.T.M.A.) operates a ferry service between terminals in Souris, Prince Edward Island, and Cap-aux-Meules, on the islands. CTMA also operates a seasonal cruise ferry service between the islands and Montreal, on the Quebec mainland.[25]

The Magdalen Islands Airport, at Havre-aux-Maisons, offers scheduled air service to the mainland of Quebec and, seasonally, to the French overseas collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon.

See also

- List of regional county municipalities and equivalent territories in Quebec

- Quebec Route 199, the only provincial highway on the islands

- Coopérative de transport maritime et aérien, the ferry company serving the Magdalen Islands

- Municipal reorganization in Quebec

- List of Quebec regions

- Coins of the Magdalen Islands (numismatic history).

- Alexis Bélanger

References

-

K.G. Andrew Hamilton (2002). "Iles-de-la-Madeleine (Magdalen Is.): a glacial refugium for short-horned bugs (Homoptera: Auchenorrhyncha)?" (PDF). Le Naturaliste Canadien. p. 36. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

All the archipelago except Le Corps Mort now lie on a single submerged plateau surrounded by shallow, sun-warmed waters which gives the islands a long, mild summer for their latitude. This plateau is a weakly sloped mound resembling a huge alluvial fan 130 by 150 km; but it is in fact covered by a rather thin layer of sediment of modern origin as all sediments older than 20,000 years have been removed from the Magdalen shelf (Loring and Nota, 1973). The plateau's convex shape is formed by a "salt dome" of ancient origin.

-

"Magdalen Islands". Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. Archived from the original on 2012-06-16. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

The Magdalen Islands form an archipelago located in the centre of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. In total, the land, dunes and offshore sand bars of the islands comprise about 200 square kilometres.

- The Archipelago

- "Ecotourism at its best". Iles Madeleine. 2008. Archived from the original on 2013-10-13. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

As the salt dome below the ground boiled up, the petrified seabed above "cracked" as it rose up.

- Antoine Dion-Ortega (November 2012). "Fossil fuel exploration in Quebec: Uncertainty rules". CIM magazine. Archived from the original on 2014-08-03. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

Some 80 kilometres east of the Magdalen Islands, across the border from Newfoundland and Labrador, lies the 30-kilometre-long by 12-kilometre-wide Old Harry structure.

-

Dennis S. Kostick (1995). "Salt" (PDF). USGS Mineral Resources Program. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2014-09-09.

A mine accident occurred on April 28 at Canadian Salt Co., Ltd.'s Mines Saleine underground rock salt operation in the St. Magdalen Islands, Quebec. Ocean water began entering the mine around the mine shaft, which was situated 250 meters below sea level, and continued to flood until mine engineers tried to stabilize the waterflow, which was calculated to be about 240 liters per minute.

- "The disappearing islands". CBC News. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

For decades, efforts have been underway to tame the effects of erosion on the Magdalen Islands, an archipelago in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. But the effects of climate change left these tiny islands vulnerable when it came to facing two powerful and unpredictable storms in less than a year.

- "The Canadian islands crumbling into the sea". Washington Post. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

They're in the middle of this gulf, which used to be covered with ice for a large part of the winter and kind of protected these islands from the winter storms

- "Once protected by ice, Canada's crumbling Magdalen Islands face disaster". Washington Post. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

Season after season, storm after storm, it is becoming clearer that the sea, which has always sustained these islands, is now their greatest threat

- Martijn, Charles (2003). "Early Mikmaq Presence in Southern Newfoundland: An Ethnohistorical Perspective, c.1500-1763". Newfoundland and Labrador Studies. 19 (1): 44–102. ISSN 1715-1430. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- Toponymie du Québec

- Bressanin, Anna; Banas, Anne (24 May 2017). "A tempestuous isle of 1,000 shipwrecks". BBC Travel. BBC. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- "2011 Community Profiles". 2011 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. July 5, 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- "2006 Community Profiles". 2006 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. March 30, 2011. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- "2001 Community Profiles". 2001 Canadian Census. Statistics Canada. February 17, 2012.

- Statistics Canada: 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 census

- http://www.tourismeilesdelamadeleine.com/en/discover-the-islands/useful-informations/climate/

- "Magdalen Islands ferry stuck - most ice in two decades". Pei Canada. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- Page, Julia (8 February 2018). "Bad season seal hunt in Magdalen Islands". CBC. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- , accessed 23 June 2016.

- Dennis, B. The ice used to protect them. Now their island is crumbling into the sea. Washington Post, 31 October 2019.

- , accessed 16 March 2012.

- , accessed 23 June 2016.

- Windsor Salt Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Schedule and rates - Ferry - Sea links crossing Îles de la Madeleine and Prince Edouard Island ferry, cruise on St-Lawrence Archived 2009-01-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Climate data was recorded on Grindstone Island in the community of Cap-aux-Meules from August 1890 to February 1983 and at Îles-de-la-Madeleine Airport from May 1983 to present.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Îles-de-la-Madeleine. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Magdalen Islands. |

- Municipalité des Îles-de-la-Madeleine

- Municipalités et villes de la Gaspésie

- Magdalen Islands tourist association

- The official tourist site of the islands

- Quebec tourism information on the Magdalen Islands including a map (with the French names)