Hops

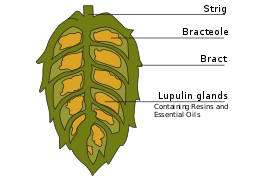

Hops are the flowers (also called seed cones or strobiles) of the hop plant Humulus lupulus.[1] They are used primarily as a bittering, flavouring, and stability agent in beer, to which, in addition to bitterness, they impart floral, fruity, or citrus flavours and aromas.[2] Hops are also used for various purposes in other beverages and herbal medicine. The hop plant is a vigorous, climbing, herbaceous perennial, usually trained to grow up strings in a field called a hopfield, hop garden (nomenclature in the South of England), or hop yard (in the West Country and US) when grown commercially. Many different varieties of hops are grown by farmers around the world, with different types used for particular styles of beer.

The first documented use of hops in beer is from the 9th century, though Hildegard of Bingen, 300 years later, is often cited as the earliest documented source.[3] Before this period, brewers used a "gruit", composed of a wide variety of bitter herbs and flowers, including dandelion, burdock root, marigold, horehound (the old German name for horehound, Berghopfen, means "mountain hops"), ground ivy, and heather.[4] Early documents include mention of a hop garden in the will of Charlemagne's father, Pepin III.[5]

Hops are also used in brewing for their antibacterial effect over less desirable microorganisms and for purported benefits including balancing the sweetness of the malt with bitterness and a variety of flavours and aromas.[2] Historically, traditional herb combinations for beers were believed to have been abandoned when beers made with hops were noticed to be less prone to spoilage.[6]

History

The first documented hop cultivation was in 736, in the Hallertau region of present-day Germany,[7] although the first mention of the use of hops in brewing in that country was 1079.[8] However, in a will of Pepin the Short, the father of Charlemagne, hop gardens were left to the Cloister of Saint-Denis in 768. Not until the 13th century did hops begin to start threatening the use of gruit for flavouring. Gruit was used when the nobility levied taxes on hops. Whichever was taxed made the brewer then quickly switch to the other. In Britain, hopped beer was first imported from Holland around 1400, yet hops were condemned as late as 1519 as a "wicked and pernicious weed".[9] In 1471, Norwich, England, banned use of the plant in the brewing of ale ("beer" was the name for fermented malt liquors bittered with hops; only in recent times are the words often used as synonyms).

In Germany, using hops was also a religious and political choice in the early 16th century. There was no tax on hops to be paid to the Catholic church, unlike on gruit. For this reason the Protestants preferred hopped beer.[10]

Hops used in England were imported from France, Holland and Germany with import duty paid for those; it was not until 1524 that hops were first grown in the southeast of England (Kent) when they were introduced as an agricultural crop by Dutch farmers. Therefore, in the hop industry there are many words which originally were Dutch words (see oast house). Hops were then grown as far north as Aberdeen, near breweries for convenience of infrastructure.

According to Thomas Tusser's 1557 Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry:

"The hop for his profit I thus do exalt,

It strengtheneth drink and it flavoureth malt;

And being well-brewed long kept it will last,

And drawing abide, if ye draw not too fast."[11]

In England there were many complaints over the quality of imported hops, the sacks of which were often contaminated by stalks, sand or straw to increase their weight. As a result, in 1603, King James I approved an Act of Parliament banning the practice by which "the Subjects of this Realm have been of late years abused &c. to the Value of £20,000 yearly, besides the Danger of their Healths".[12]

Hop cultivation was begun in the present-day United States in 1629 by English and Dutch farmers.[13] Before prohibition, cultivation was mainly centred around New York, California, Oregon, and Washington state. Problems with powdery mildew and downy mildew devastated New York's production by the 1920s, and California only produces hops on a small scale.[14]

Hop bars were used before modern machinery was invented to make the holes for the hop poles.[15]

World production

Hops production is concentrated in moist temperate climates, with much of the world's production occurring near the 48th parallel north. Hop plants prefer the same soils as potatoes and the leading potato-growing states in the United States are also major hops-producing areas;[16] however, not all potato-growing areas can produce good hops naturally: soils in the Maritime Provinces of Canada, for example, lack the boron that hops prefer.[16] Historically, hops were not grown in Ireland, but were imported from England. In 1752 more than 500 tons of English hops were imported through Dublin alone.[17]

Important production centres today are the Hallertau in Germany,[18] the Žatec (Saaz) in the Czech Republic, the Yakima (Washington) and Willamette (Oregon) valleys, and western Canyon County, Idaho (including the communities of Parma, Wilder, Greenleaf, and Notus).[19] The principal production centres in the UK are in Kent (which produces Kent Goldings hops), Herefordshire, and Worcestershire.[20][21] Essentially all of the harvested hops are used in beer making.

| Hop producing country | 2017 hop output in tonnes (t)[22] |

|---|---|

| United States | 44,324 |

| Germany | 39,000 |

| Czech Republic | 6,100 |

| China | 4,500 |

| Poland | 2,826 |

| Slovenia | 2,600 |

| UK/England | 1,400 |

| Australia | 1,200 |

| Spain | 950 |

| New Zealand | 760 |

| Argentina | 200 |

Cultivation and harvest

Although hops are grown in most of the continental United States and Canada,[23] cultivation of hops for commercial production requires a particular environment. As hops are a climbing plant, they are trained to grow up trellises made from strings or wires that support the plants and allow them significantly greater growth with the same sunlight profile. In this way, energy that would have been required to build structural cells is also freed for crop growth.[24]

The hop plant's reproduction method is that male and female flowers develop on separate plants, although occasionally a fertile individual will develop which contains both male and female flowers.[25] Because pollinated seeds are undesirable for brewing beer, only female plants are grown in hop fields, thus preventing pollination. Female plants are propagated vegetatively, and male plants are culled if plants are grown from seeds.[26]

Hop plants are planted in rows about 2 to 2.5 metres (7 to 8 ft) apart. Each spring, the roots send forth new bines that are started up strings from the ground to an overhead trellis. The cones grow high on the bine, and in the past, these cones were picked by hand. Harvesting of hops became much more efficient with the invention of the mechanical hops separator, patented by Emil Clemens Horst in 1909.

Harvest comes near the end of summer when the bines are pulled down and the flowers are taken to a hop house or oast house for drying. Hop houses are two-story buildings, of which the upper story has a slatted floor covered with burlap. Here the flowers are poured out and raked even. A heating unit on the lower floor is used to dry the hops. When dry, the hops are moved to a press, a sturdy box with a plunger. Two long pieces of burlap are laid into the hop press at right angles, the hops are poured in and compressed into bales.

Hop cones contain different oils, such as lupulin, a yellowish, waxy substance, an oleoresin, that imparts flavour and aroma to beer.[27] Lupulin contains lupulone and humulone, which possess antibiotic properties, suppressing bacterial growth favoring brewer's yeast to grow. After lupulin has been extracted in the brewing process the papery cones are discarded.

Migrant labor and social impact

.jpg)

The need for massed labor at harvest time meant hops-growing had a big social impact. Around the world, the labor-intensive harvesting work involved large numbers of migrant workers who would travel for the annual hops harvest. Whole families would participate and live in hoppers' huts, with even the smallest children helping in the fields.[28][29] The final chapters of W. Somerset Maugham's Of Human Bondage and a large part of George Orwell's A Clergyman's Daughter contain vivid descriptions of London families participating in this annual hops harvest. In England, many of those picking hops in Kent were from eastern areas of London. This provided a break from urban conditions that was spent in the countryside. People also came from Birmingham and other Midlands cities to pick hops in the Malvern area of Worcestershire. Some photographs have been preserved.[30]

Particularly in Kent, because of a shortage of small-denomination coin of the realm, many growers issued their own currency to those doing the labor. In some cases, the coins issued were adorned with fanciful hops images, making them quite beautiful.[31]

.jpeg)

In the US, Prohibition had a major impact on hops productions, but remnants of this significant industry in West and Northwest US are still noticeable in the form of old hop kilns that survive throughout Sonoma County, among others. Florian Dauenhauer, of Santa Rosa in Sonoma County, became a manufacturer of hop-harvesting machines in 1940, in part because of the hop industry's importance to the county. This mechanization helped destroy the local industry by enabling large-scale mechanized production, which moved to larger farms in other areas.[32] Dauenhauer Manufacturing remains a current producer of hop harvesting machines.

Chemical composition

In addition to water, cellulose, and various proteins, the chemical composition of hops consists of compounds important for imparting character to beer.[2][33]

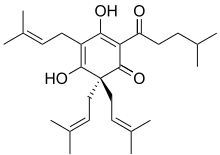

Alpha acids

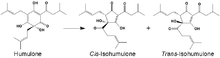

Probably the most important chemical compound within hops are the alpha acids or humulones. During wort boiling, the humulones are thermally isomerized into iso-alpha acids or isohumulones, which are responsible for the bitter taste of beer.[34]

Beta acids

Hops contain beta acids or lupulones. These are desirable for their aroma contributions to beer.

Essential oils

The main components of hops essential oils are terpene hydrocarbons consisting of myrcene, humulene and caryophyllene.[33] Myrcene is responsible for the pungent smell of fresh hops. Humulene and its oxidative reaction products may give beer its prominent hop aroma. Together, myrcene, humulene, and caryophyllene represent 80 to 90% of the total hops essential oil.[33]

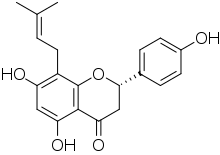

Flavonoids

Xanthohumol is the principal flavonoid in hops. The other well-studied prenylflavonoids are 8-prenylnaringenin and isoxanthohumol. Xanthohumol is under basic research for its potential properties, while 8-prenylnaringenin is a potent phytoestrogen.[35][36]

Brewing

Hops are usually dried in an oast house before they are used in the brewing process.[37] Undried or "wet" hops are sometimes (since ca.1990) used.[38][39]

The wort (sugar-rich liquid produced from malt) is boiled with hops before it is cooled down and yeast is added, to start fermentation.

The effect of hops on the finished beer varies by type and use, though there are two main hop types: bittering and aroma.[2] Bittering hops have higher concentrations of alpha acids, and are responsible for the large majority of the bitter flavour of a beer. European (so-called "noble") hops typically average 5–9% alpha acids by weight (AABW), and the newer American cultivars typically range from 8–19% AABW. Aroma hops usually have a lower concentration of alpha acids (~5%) and are the primary contributors of hop aroma and (nonbitter) flavour. Bittering hops are boiled for a longer period of time, typically 60–90 minutes, to maximize the isomerization of the alpha acids. They often have inferior aromatic properties, as the aromatic compounds evaporate during the boil.

The degree of bitterness imparted by hops depends on the degree to which alpha acids are isomerized during the boil, and the impact of a given amount of hops is specified in International Bitterness Units. Unboiled hops are only mildly bitter. On the other hand, the nonbitter flavour and aroma of hops come from the essential oils, which evaporate during the boil.

Aroma hops are typically added to the wort later to prevent the evaporation of the essential oils, to impart "hop taste" (if during the final 30 minutes of boil) or "hop aroma" (if during the final 10 minutes, or less, of boil). Aroma hops are often added after the wort has cooled and while the beer ferments, a technique known as "dry hopping", which contributes to the hop aroma. Farnesene is a major component in some hops.[2] The composition of hop essential oils can differ between varieties and between years in the same variety, having a significant influence on flavour and aroma.[2]

Today, a substantial amount of "dual-use" hops are used, as well. These have high concentrations of alpha acids and good aromatic properties. These can be added to the boil at any time, depending on the desired effect.[40] Hop acids also contribute to and stabilize the foam qualities of beer.[2]

Flavours and aromas are described appreciatively using terms which include "grassy", "floral", "citrus", "spicy", "piney", "lemony", "grapefruit", and "earthy".[2][41] Many pale lagers have fairly low hop influence, while lagers marketed as Pilsener or brewed in the Czech Republic may have noticeable noble hop aroma. Certain ales (particularly the highly hopped style known as India Pale Ale, or IPA) can have high levels of hop bitterness.

Brewers may use software tools to control the bittering levels in the boil and adjust recipes to account for a change in the hop bill or seasonal variations in the crop that may lead to the need to compensate for a difference in alpha acid contribution. Data may be shared with other brewers via BeerXML allowing the reproduction of a recipe allowing for differences in hop availability.

Varieties

Breeding programmes

There are many different varieties of hops used in brewing today. Historically, hops varieties were identified by geography (such as Hallertau, Spalt, and Tettnang from Germany), by the farmer who is recognized as first cultivating them (such as Goldings or Fuggles from England), or by their growing habit (e.g., Oregon Cluster).[42]

Around 1900, a number of institutions began to experiment with breeding specific hop varieties. The breeding program at Wye College in Wye, Kent, was started in 1904 and rose to prominence through the work of Prof. E. S. Salmon. Salmon released Brewer's Gold and Brewer's Favorite for commercial cultivation in 1934, and went on to release more than two dozen new cultivars before his death in 1959. Brewer's Gold has become the ancestor of the bulk of new hop releases around the world since its release.[43]

Wye College continued its breeding program and again received attention in the 1970s, when Dr. Ray A. Neve released Wye Target, Wye Challenger, Wye Northdown, Wye Saxon and Wye Yeoman. More recently, Wye College and its successor institution Wye Hops Ltd., have focused on breeding the first dwarf hop varieties, which are easier to pick by machine and far more economical to grow.[44] Wye College have also been responsible for breeding hop varieties that will grow with only 12 hours of daily light for the South African hop farmers. Wye College was closed in 2009 but the legacy of their hop breeding programs, particularly that of the dwarf varieties, is continuing as already the US private and public breeding programs are using their stock material.

Particular hop varieties are associated with beer regions and styles, for example pale lagers are usually brewed with European (often German, Polish or Czech) noble hop varieties such as Saaz, Hallertau and Strissel Spalt. British ales use hop varieties such as Fuggles, Goldings and W.G.V. North American beers often use Cascade hops, Columbus hops, Centennial hops, Willamette, Amarillo hops and about forty more varieties as the US have lately been the more significant breeders of new hop varieties, including dwarf hop varieties.

Hops from New Zealand, such as Pacific Gem, Motueka and Nelson Sauvin, are used in a "Pacific Pale Ale" style of beer with increasing production in 2014.[45]

Noble hops

The term "noble hops" is a marketing term that traditionally refers to varieties of hops low in bitterness and high in aroma.[46] They are the European cultivars or races Hallertau, Tettnanger, Spalt, and Saaz.[47] Some proponents assert that the English varieties Fuggle, East Kent Goldings and Goldings might qualify as "noble hops" due to the similar composition, but such terms never applied to English varieties. Their low relative bitterness, but strong aroma, are often distinguishing characteristics of European-style lagers, such as Pilsener, Dunkel, and Oktoberfest/Märzen. In beer, they are considered aroma hops (as opposed to bittering hops);[46] see Pilsner Urquell as a classic example of the Bohemian Pilsener style, which showcases noble hops.

As with grapes, the location where hops are grown affects the hops' characteristics. Much as Dortmunder beer may within the EU be labelled "Dortmunder" only if it has been brewed in Dortmund, noble hops may officially be considered "noble" only if they were grown in the areas for which the hop varieties (races) were named.

- Hallertau or Hallertauer – The original German lager hop; named after Hallertau or Holledau region in central Bavaria. Due to susceptibility to crop disease, it was largely replaced by Hersbrucker in the 1970s and 1980s. (Alpha acid 3.5–5.5% / beta acid 3–4%)

- Žatec (Saaz) – Noble hop, named after Žatec town, used extensively in Bohemia to flavour pale Czech lagers such as Pilsner Urquell. Soft aroma and bitterness. (Alpha acid 3–4.5% /Beta acid 3–4.5%)

- Spalt – Traditional German noble hop from the Spalter region south of Nuremberg. With a delicate, spicy aroma. (Alpha acid 4–5% / beta acid 4–5%)

- Tettnang – Comes from Tettnang, a small town in southern Baden-Württemberg in Germany. The region produces significant quantities of hops, and ships them to breweries throughout the world. Noble German dual-use hop used in European pale lagers, sometimes with Hallertau. Soft bitterness. (Alpha acid 3.5–5.5% / beta acid 3.5–5.5%)

Noble hops are characterized through analysis as having an aroma quality resulting from numerous factors in the essential oil, such as an alpha:beta ratio of 1:1, low alpha-acid levels (2–5%) with a low cohumulone content, low myrcene in the hop oil, high humulene in the oil, a ratio of humulene:caryophyllene above three, and poor storability resulting in them being more prone to oxidation.[46] In reality, this means they have a relatively consistent bittering potential as they age, due to beta-acid oxidation, and a flavor that improves as they age during periods of poor storage.[46][48]

Other uses

In addition to beer, hops are used in herbal teas and in soft drinks. These soft drinks include Julmust (a carbonated beverage similar to soda that is popular in Sweden during December), Malta (a Latin American soft drink) and kvass. Hops can be eaten, the young shoots of the vine are edible and can be cooked similar to asparagus.[49][50]

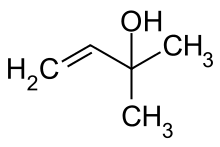

Hops may be used in herbal medicine in a way similar to valerian, as a treatment for anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.[51] A pillow filled with hops is a popular folk remedy for sleeplessness, and animal research has shown a sedative effect.[52] The relaxing effect of hops may be due, in part, to the specific degradation product from alpha acids, 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol, as demonstrated from nighttime consumption of non-alcoholic beer.[52][53] 2-methyl-3-buten-2-ol is structurally similar to tert-amyl alcohol which was historically used as an anesthetic. Hops tend to be unstable when exposed to light or air and lose their potency after a few months' storage.

Hops are of interest for hormone replacement therapy and are under basic research for potential relief of menstruation-related problems.[54]

Toxicity

Dermatitis sometimes results from harvesting hops. Although few cases require medical treatment, an estimated 3% of the workers suffer some type of skin lesions on the face, hands, and legs.[55] Hops are toxic to dogs.[56]

Fiction

Hops and hops picking form the milieu and atmosphere in the British detective novel, Death in the Hop Fields (1937) by John Rhode.[57] The novel was subsequently issued in the United States under the title, The Harvest Murder.[58]

See also

- Gruit, an old-fashioned herb mixture used for bittering and flavouring beer, popular before the extensive use of hops

- Humulus lupulus, the hop plant

- Mugwort, an herb historically used as a bitter in beer production

- Oast house, a building designed for drying hops

- Rhamnus prinoides, a plant whose leaves are used in the Ethiopian variety of mead called tej

References

- "University of Minnesota Libraries: The Transfer of Knowledge. Hops-Humulus lupulus". www.lib.umn.edu. Lib.umn.edu. 13 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Schönberger C, Kostelecky T (16 May 2012). "125th Anniversary Review: The Role of Hops in Brewing". Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 117 (3): 259–267. doi:10.1002/j.2050-0416.2011.tb00471.x.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Hornsey, Ian S. (2003). A History of Beer and Brewing. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 305. ISBN 9780854046300.

- "Understanding Beer – A Broad Overview of Brewing, Tasting and Analyzing Beer – October 12th, 2006, Beer & Brewing, The Brewing Process". www.jongriffin.com. Jongriffin.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Michael Jackson (1988). The New World World Guide to Beer. Running Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-89471-884-7.

- F. G. Priest; Iain Campbell (2003). Brewing microbiology. Springer. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-306-47288-6.

- Ian Hornsey (31 October 2007). Brewing. p. 58. ISBN 9781847550286.

- H.S. Corran (23 January 1975). History of Brewing. David and Charles PLC. p. 303. ISBN 978-0715367353.

- Richard W. Unger (2004). Beer in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 100.

- Mika Rissanen. "The Reformation had some help from hops". www.academia.edu. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- Charles Knight (1832). Antiquity of Beer. The Penny Magazine. p. 3.

- Adam Anderson (1764). An Historical and Chronological Deduction of the Origin of Commerce. 1. p. 461.

- Charles W. Bamforth (1998). Beer: tap into the art and science of brewing. Plenum Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-306-45797-5.

- Knight, Paul D. "HOPS IN BEER". USA Hops. Hop Growers of America. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Annual Report of the Commissioner of Patents, Part 2; Part 4. US Patent office. 1858. p. 291.

- Peicanada

- "The London magazine, 1752", page 332

- Summary of Reports: Nürnberg, Germany, 14 November 2006, International Hop Growers' Convention: Economic Committee

- "NCGR-Corvallis Humulus Genetic Resources". www.ars-grin.gov. Ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Norman Moss, A Fancy to Worcesters Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Agricultural research Service, US Department of Agriculture

- "Herefordshire Through Time – Welcome". www.smr.herefordshire.gov.uk. Smr.herefordshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- International Hop Growers' Convention - Economic Commission Summary Reports (FAO).

- "Humulus lupulus L. common hop". USDA Plants database. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- Keegstra, Kenneth (1 October 2010). "Plant Cell Walls". Plant Physiology. 154 (2): 483–486. doi:10.1104/pp.110.161240. ISSN 1532-2548. PMC 2949028. PMID 20921169.

- C. C. Ainsworth (15 June 1999). Sex Determination in Plants. Garland Science. p. 146. ISBN 9780203345993.

- "Interactive Agricultural Ecological Atlas of Russia and Neighboring Countries. Economic Plants and their Diseases, Pests and Weeds. Humulus lupulus". www.agroatlas.ru. Agroatlas.ru. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Andrew, Sewalish. "Hops: Anatomy and Chemistry 101". bioweb.uwlax.edu. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- "Connie's Homepage – Hop Picking in Kent". www.btinternet.com. Btinternet.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "George Orwell: Hop-picking". www.theorwellprize.co.uk. Theorwellprize.co.uk. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Smith, Keith. Around Malvern in old photographs.. Alan Sutton Publishing, Gloucester. ISBN 0-86299-587-6.

- "The Furiners: A Forgotten Story". www.brewtek.ca. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Gaye LeBaron (29 June 2008). "Hops, once king of county's crops, helped put region on map". Press Democrat. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- M. Verzele (2 January 1986). "100 Years of Hop Chemistry and Its Relevance to Brewing". Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 92 (1): 32–48. doi:10.1002/j.2050-0416.1986.tb04372.x. ISSN 2050-0416.

- Denis De Keukeleire (2000). "Fundamentals of beer and hop chemistry". Química Nova. 23 (1): 108–112. doi:10.1590/S0100-40422000000100019. ISSN 0100-4042.

- Stevens, Jan F; Page, Jonathan E (1 May 2004). "Xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids from hops and beer: to your good health!". Phytochemistry. 65 (10): 1317–1330. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.04.025. PMID 15231405.

- Milligan, S; Kalita, J; Pocock, V; Heyerick, A; Cooman, L De; Rong, H; Keukeleire, D De (2002). "Oestrogenic activity of the hop phyto-oestrogen, 8-prenylnaringenin". Reproduction. 123 (2): 235–242. doi:10.1530/rep.0.1230235.

- James S. Hough (1991). The Biotechnology of Malting and Brewing. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39553-3.

- Elizabeth Aguilera (10 September 2008). "Hop harvest yields hip beer for brewer". Denver Post.

- Kristin Underwood It's Harvest Time at the Sierra Nevada Brewery. Treehugger. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- John Palmer (2006). How to Brew. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-0-937381-88-5.

- Hough JS, Briggs DE, Stevens R, Young TW (6 December 2012). Malting and Brewing Science: Volume II Hopped Wort and Beer. Springer. p. 867. ISBN 978-1-4615-1799-3.

- "Brewery History: 121, pp. 94–112". www.breweryhistory.com. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- Capper, Allison; Darby, Peter (24 March 2014). "What makes British Hops Unique in the world of Hop Growing?" (PDF). www.britishhops.org.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "History of Hops". British Hop Association. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- "On Trade Preview 2014" (PDF). www.ontrade.co.uk.

- Andrew Walsh (30 November 2001). "An Investigation into the Purity of Noble Hop Lineage". www.morebeer.com. More Beer; In: Brewing Techniques – Vol. 6, No.2. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Hop growers union of the Czech Republic". www.czhops.cz. Czhops.cz. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Hop Chemistry: Homebrew Science". www.byo.com. Byo.com. 28 April 2000. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "9 Perennial Vegetables You Can Plant Once, Harvest Forever … And Never Worry About Again". 8 March 2017. torageprepper.com. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Alexi Duggins (18 May 2015). "'It's like eating a hedgerow': why do hop shoots cost €1,000 a kilo?". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Plants for a Future: Humulus lupulus Plants for a Future. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- Franco L, Sánchez C, Bravo R, Rodriguez A, Barriga C, Juánez JC (2012). "The sedative effects of hops (Humulus lupulus), a component of beer, on the activity/rest rhythm". Acta Physiol Hung. 99 (2): 133–9. doi:10.1556/APhysiol.99.2012.2.6. PMID 22849837.

- Franco L, Sánchez C, Bravo R, Rodríguez AB, Barriga C, Romero E, Cubero J (2012). "The sedative effect of non-alcoholic beer in healthy female nurses". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e37290. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037290. PMC 3399866. PMID 22815680.

- Keiler AM, Zierau O, Kretzschmar G (2013). "Hop extracts and hop substances in treatment of menopausal complaints". Planta Med. 79 (7): 576–9. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1328330. PMID 23512496.

- "Purdue University: Center for New Crops and Plant Products. Humulus lupulus L". www.hort.purdue.edu. Hort.purdue.edu. 7 January 1998. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Animal Poison Control Center. Hops". www.aspca.org. ASPCA. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Rhode, John (1937). Death in the Hop Fields (First; hardcover ed.). UK: Dodd, Mead & Company.

- Rhode, John. The Harvest Murder. US.