Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland

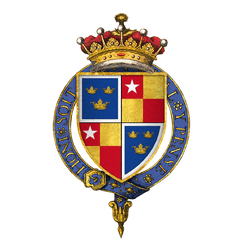

Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland, Marquess of Dublin, and 9th Earl of Oxford KG (16 January 1362 – 22 November 1392) was a favourite and court companion of King Richard II of England. He was the ninth Earl of Oxford and the first and only Duke of Ireland and Marquess of Dublin.

Robert de Vere | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Ireland | |

Robert de Vere, Duke of Ireland, fleeing Radcot Bridge, 1387, taken from the Gruthuse manuscript of Froissart's Chroniques (circa 1475) | |

| Born | 16 January 1362 Robert de Vere |

| Died | 22 November 1392 (aged 30) Louvain |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Father | Thomas de Vere, 8th Earl of Oxford |

| Mother | Maud de Ufford |

Early life

Robert de Vere was the only son of Thomas de Vere, 8th Earl of Oxford and Maud de Ufford.[1] He succeeded his father as 9th Earl in 1371, and was created Marquess of Dublin in 1385. The next year he was created Duke of Ireland. He was thus the first marquess, and only the second non-princely duke (after Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster in 1337), in England. King Richard's close friendship to de Vere was disagreeable to the political establishment. This displeasure was exacerbated by the earl's elevation to the new title of Duke of Ireland in 1386.[2] His relationship with King Richard was very close and rumored by Thomas Walsingham to be homosexual.[3]

Robert, Duke of Ireland, was married to Philippa de Coucy, the King's first cousin (her mother, Isabella, was the sister of the King's father, Edward, the Black Prince and the eldest daughter of Edward III). Robert had an affair with Agnes de Launcekrona, a Czech lady-in-waiting of Richard's queen, Anne of Bohemia. In 1387, the couple were separated and eventually divorced; Robert took Launcekrona as his second wife.

Downfall

Since Robert was hugely unpopular with the other nobles and magnates, his close relationship with King Richard was one of the catalysts for the emergence of an organised opposition to Richard's rule in the form of the Lords Appellant.

In 1387, Ireland led Richard's forces to defeat at Radcot Bridge outside Oxford, against the forces of the Lords Appellant. He fled the field and his forces were left leaderless and compelled into ignominious surrender.

He was attainted and sentenced to death in absentia by the Merciless Parliament of 1388, which also made him forfeit his titles and lands. People associated with him were also affected, for the parliament also dismissed his Irish Administration, composed of John Stanley, his deputy, who had been serving as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, James Butler, 3rd Earl of Ormond, the governor, Bishop Alexander de Balscot of Meath, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, and Sir Robert Crull, Lord High Treasurer of Ireland.[4] Fortunately for him, he had already fled abroad into exile directly after Radcot Bridge.

Death

He died in or near Louvain in 1392 of injuries sustained during a boar hunt. Three years later, on the anniversary of his death, 22 November 1395, Richard II had his embalmed body brought back to England for burial. It was recorded by the chronicler Thomas Walsingham that many magnates did not attend the re-burial ceremony because they 'had not yet digested their hatred' of him. The king had the coffin opened to kiss his lost friend's hand and to gaze on his face one last time.[5]

Succession

After Ireland's death, his uncle Sir Aubrey de Vere, was restored to the family titles and estates, becoming 10th Earl of Oxford. The Dukedom of Ireland and Marquessate of Dublin became extinct.

Footnotes

- Richardson IV 2011, pp. 268–9.

- McKisack (1959), pp. 425, 442–3.

- Saul, Nigel (1997). Richard II. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07003-9. p. 437.

- Peter Crooks, The 'Calculus of Faction' and Richard II's Ireland, in Fourteenth Century England, V, ed. Nigel Saul. Woodbridge, England: The Boydell Press, 2008. 111-112 ISBN 978-1-84383-387-1

- Saul, 461.

References

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham. IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 1460992709

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The 8th Earl of Oxford |

Lord Great Chamberlain 1371–1388 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Exeter |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by The Duke of York |

Justice of Chester 1387–1388 |

Succeeded by The Duke of Gloucester |

| Peerage of England | ||

| Preceded by Thomas de Vere |

Earl of Oxford 1371–1388 |

Succeeded by Aubrey de Vere |