Load shifting

Load shifting is a dangerous phenomenon in water, air, and ground transportation where many small moveable items (ex. coal) shift or spill toward the downward side when the cargo vehicle consistently tips past 10 or 15 degrees. Over time, this can lead to escalating tilting of the cargo vehicle and can lead to tipping or eventual capsizing. Such a dangerous occurrence is prevented by active load management, avoidance of high sea conditions, and proper container/bulkhead design.

On a cargo airplane, a professional loadmaster is necessary to prevent the highly-dangerous phenomenon of load shifting. If a plane begins to take off with unsecured cargo, some of the cargo may slide to the aft of the airplane, resulting in a catastrophic switch in the centre of gravity and a stall condition.

Ships

Ships are used to transport a majority of today's goods which is approximately 90% of all non bulk cargo.[1] Handling loads such as what cargo creates, is part boat design and part operation.

Design

There are many types of loads that vessels carry that can shift, including container, bulk, liquids, and fluids that leak into bilges

Shipping containers

To design a boat to deal with loads such that they do not shift in the modern world is rather simple. Most loads are in containers measuring 1/2, 1 or 2 TEUs, which are locked to each other and the deck with twist-locks, and occasionally reinforce the structures with steel cables. When containers become an issue with the stability of the boat, for example all the containers broke free and are hanging over the side shifting the center of mass, most ships will cut the containers loose and add extra ballast water to compensate.[2] If objects fall around in containers, it isn't a huge deal unless they knock the container free, as container ships carry thousands of containers so having a couple with shifting loads, isn't a big deal. It also makes it easier if loads are shifting inside because the container itself will contain loads and make it so they can only shift a few feet.

Bulk cargo

Just like fluids, bulk cargo can and will shift if a ship rolls enough to permit. Shifting loads of bulk cargo can be very dangerous. In order to eliminate this threat, on most ships that carry bulk, they tend to be lower in the water and carry cargo up to the deck and as due to the nature of bulk not a one it. If it becomes a dangerous passage, sometimes a honeycomb like structure will be added to prevent bulk from shifting enough to endanger the vessel and its crew.[3][4]

Tank

Fluids are the easiest thing to shift, and the most dangerous due to the free surface effect. As a boat rolls, liquids tend to shift toward the lowest part of the vessel. This is the free surface effect. When this happens more weight is now being thrown toward the low side and will cause a more severe roll or potential capsize. To minimize/reduce this risk, tanks are built in sections split up by perforated panels. These panels prevent sloshing, but still allow liquid to transfer keeping the levels amount the tank equal.[3]

Planes

Design

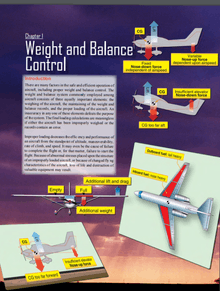

Cargo planes are designed to carry large loads long distances at speed. In order to stay relatively stable they must prevent loads from breaking free or shifting, because unbalanced loads on an aircraft can lead to a major catastrophe. The reason for this, is if the center of mass leaves an invisible box, called the flight zone, the plane is no longer stable and the pilots have to fight the aircraft to stay aloft.[6]

Loading

Similar to shipping many countries have rules for loading aircraft. There are no worldwide regulations but many are similar. The US Federal Aviation Authority publishes specific guidelines on loading light aircraft, single-engine aircraft, multi-engine aircraft, commuter and large aircraft, and helicopters.[6]

References

- "Shipping and World Trade". International Chamber of Shipping.

- Barrass, Bryan & Captain D. R. Derrett (2006). Ship Stability for Masters and Mates (6th edition). Elsevier Science. ISBN 9780750667845.

- Tupper, E. C. (2004). Introduction to Naval Architecture: Formerly Muckle's Naval Architecture for Marine Engineers (4th edition). Elsevier Science. ISBN 9780750665544.

- Lei Ju, Yanzhuo Xue, Dracos Vassalos, Yang Liu, Baoyu Ni (2017). Numerical investigation of rolling response of a 2D rectangular hold, partially filled with moist bulk cargo. ScienceDirect Journals. pp. 348–362.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Safe transport of containers".

- "Weight and Balance Handbook (FAA-H-8083-1B)" (PDF). US Department of Transportation. 2016.