Liverpool Road

Liverpool Road is a street in Islington, North London. It covers a distance of 1 1⁄4 miles (2.0 km) between Islington High Street and Holloway Road, running roughly parallel to Upper Street through the area of Barnsbury. It contains several attractive terraces of Georgian houses and Victorian villas, many of which are listed buildings. There are a number of pubs, small businesses and restaurants along its route, as well as some secluded garden squares. The vast majority of the street is residential, with a bustling shopping and business area at the southern, Angel, end.

Liverpool Road | |

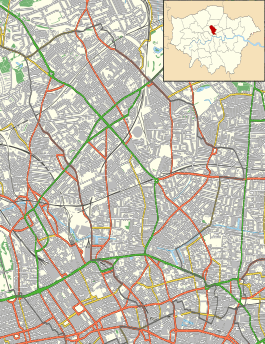

Location within Islington | |

| Former name(s) | Back Road |

|---|---|

| Maintained by | London Borough of Islington |

| Length | 1.25 mi (2.01 km) |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Postal code | N1, N7 |

| Nearest Tube station | |

| Coordinates | 51.5422°N 0.1064°W |

| North end | Holloway Road |

| South end |

|

History

Liverpool Road was formerly named the Back Road, one of a trio of roads with Upper Street and Lower Street (later renamed Essex Road) meeting at the Angel Inn. By the late 16th century the Back Road ran mostly through open country from Holloway Road at a point named Ring Cross to the High Street in Islington village. It bypassed Upper Street and connected with lanes across the western part of the parish. The Back Road was primarily a drovers' road where cattle would be rested before the final leg of their journey to Smithfield Livestock Market. Pens and sheds known as layers or lairs were erected along the road to accommodate the animals.[1]

Around 1761, a turnpike tollgate was erected just beyond the Angel Inn at the entrance to Islington village at the end of White Lion Street. It was moved in about 1800 nearer to Liverpool Road, but proving a cause of accidents because of a sharp turn, in 1808 it was moved again to a final position midway between the two sites. In 1766, an Act of Parliament fixed a site for a tollgate at the northern end of Liverpool Road at the junction with Holloway Road.[2]

Suburban development began to the south of Holloway Road around the late 1760s with the construction of Paradise Row at the northern end of Liverpool Road.[3]

During the period after Waterloo, a rapid rise in population put a premium on building land contiguous to London. Starting in the 1820s, plots in Barnsbury were sold on building leases and a flood of speculative building followed.[4]

The developments along Liverpool Road were mostly on fields belonging to different owners, leading to a remarkable number of subsidiary names, including:

- Bride, Anns, Barford, Manchester, Park, Barnsbury, Barnsbury Park, King Edward, Wellington, Strahan, Cloudesley, Elizabeth, Felix, Liverpool and Paradise Terraces

- Felix, Seymour, Morgans, Park, Chapel and Trinidad Places; Park Place West

- Albion, Felix, Oldfield and Lowther Cottages

- Barnsbury and Albion Villas

- Paradise and Mount Rows

- Nowells Buildings

.jpg)

The Back Road became known as Liverpool Road in 1826, taking its name from the Tory Prime Minister Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, known for his repressive measures to maintain order after the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. The name change was formalised in 1868 when the Vestry decided that “the Liverpool Road be so called from the Upper Street to Holloway Road and the houses re-numbered alternately”.[5][6] Many of the subsidiary names continued to be used for years afterwards.

The house building developments were originally planned for the “comfortably off”, wanting to move from congested central London to the more rural suburb of Islington. However, from the 1850s the new railways tempted suburban dwellers to more distant and still countrified areas. Barnsbury was gradually abandoned by the prosperous, and its houses turned into tenements and flats with absentee landlords. The 1860s saw an influx of clerks, schoolmasters, printers, jewellers, milliners, dressmakers, servants and bricklayers.[7] Censuses show house occupancy changing from single households with a servant, to multiple household occupancy, although Charles Booth’s poverty map of c.1890 still shows most Liverpool Road households as “Fairly comfortable. Good ordinary earnings”. In the first half of the 20th century the street, as with much of Islington and its population, became impoverished.

Liverpool Road suffered damage from high explosives during the Second World War, including:

- Nos. 309/311/313 Liverpool Road took a direct hit during a bombing raid on the night of 19th October 1940 and were completely destroyed.[8] The present Wynn Court was later built on the site.

- St Mary Magdalene school and the surrounding area were destroyed by a bomb on On 7th/8th October 1940.

- Granary Square 1940/41

- London Fever Hospital

- On 6 December 1944 a V-2 rocket landed close to Liverpool Road at the junction of Mackenzie and Chalfont Roads, on the site of the present Paradise Park. The Prince of Wales pub was devastated, killing 68 and injuring 99 people, in the worst V-2 attack on Islington.[9]

After the Second World War much housing in Islington was chronically neglected and damaged, and was taken into local authority ownership. Many older properties were demolished and replaced with council housing, including in Liverpool Road.

Starting about 1960 middle class and professional householders began returning to Islington, to houses which were once elegant but now, more often than not, were endowed with Victorian plumbing hardly suited for modern living. Journalists, architects, lawyers, accountants, teachers and designers were attracted by the style and size of the Regency and Victorian houses and squares[10] and the opportunity to acquire large, characterful properties at prices they could afford, with easy access to the City of London, Westminster and the West End. Consequently house values soon soared, a trend which has continued to the present.

Liverpool Road today houses a diverse community of different ethnicities and varying levels of income, occupying a mixture of houses and flats, which are owned or rented, both privately and as social housing.

Famous residents

Nos. 377-379 Liverpool Road was the residence of Robert Seymour, known for his caricatures and for his illustrations for The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens. In 1836 he had several disagreements with Dickens over the illustrations for Pickwick, and may also have been depressed about his finances and career. In the early hours of 20 April, he walked out into the summer-house in the garden behind his home (then named 16 Park Place West) and wrote a farewell to his “Best and dearest of wives”, blaming only his “own weakness and infirmity”. He set up his fowling piece (shotgun) with a string on its trigger, and shot himself dead.[11][6][12][13][14]

A commemorative plaque at no. 60 Liverpool Road marks a top floor studio where Derek Jarman, English film director, gay rights activist and author lived between 1967 and 1969. It was here he worked on artwork and costumes for Sadler’s Wells Opera’s production of Don Giovanni in 1968.[15][16]

No. 533 Liverpool Road displays a blue plaque unveiled by the Huguenot Society in 2017, commemorating the British artist Peter Paillou, best known for his paintings of birds.[17] The terrace was built in 1766 as Paradise Row, and Paillou lived in the house between 1776 and 1780.[18]

Other residents have included:

- Jenny Logan (1942- ), actress, most familiar as the Shake n' Vac lady, lived at no. 323

- Anton Rodgers (1933-2007), actor, lived at no. 323

- Jane Tryphoena Stephens (1812?-1896), actress, kept a tobacconist’s shop at no. 39 before taking to the stage in 1840

Places of interest

Pubs

Liverpool Road is supplied with several pubs, formerly to refresh cattle drovers and visitors to the Royal Agricultural Hall, more recently for local residents, including:[19][20]

- Pied Bull (no. 1; 1797, now closed)

- Islington Town House, originally the Agricultural Hotel (no. 13; 1865)

- Angelic, originally the George (no. 57; 1824)

- Pig and Butcher, originally the White Horse Hotel (no. 80; 1827)

- Regent, originally the Prince Regent (no. 201; 1823)

- Barnsbury, originally the Windsor Castle (nos. 209-211; 1856, rebuilt 1937)

- Rainbow (no. 200; 1833, rebuilt 1879, now closed)

- King’s Arms (no. 264; 1793, now closed)

- Adelaide Arms (no. 385; 1839, now closed)

- Gallagher's, originally the Albion (no. 412; 1856, now demolished)

- Duchess of Kent, originally the Fox and Fiddle (no. 441; 1843)

- Adam and Eve (no. 475; 1805, now closed)

- Victoria Tavern (junction with 203 Holloway Road; 1841)

Chapel Market and Angel Central

At its southern, Angel end, Liverpool Road parts from Islington High Street at the former Pied Bull pub. Moving northwards, the street passes Chapel Market, Angel Central shopping centre, and other shops and supermarkets until reaching Tolpuddle Street. From there onwards, the remaining 90% of the length of the street is primarily residential, with a few small businesses.

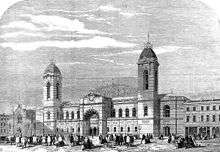

Royal Agricultural Hall

The Royal Agricultural Hall (originally named the Agricultural Hall) was the primary exhibition site for London until the Second World War and the largest building of its kind, holding up to 50,000 people.[21]

It was built in 1862 by the Smithfield Club on the site of William Dixon's cattle lairs, at a cost of £32,000. The construction was inspired by the Crystal Palace, which had been designed for the Great Exhibition of 1851. The original purpose of the Agricultural Hall and its location were related specifically to its proximity to Smithfield, the great livestock market, and took advantage of Liverpool Road’s function as a cattle route. The hall was 75 ft high and the arched glass roof spanned 125 ft. It was built for the first annual Smithfield Show in December 1862 but was subsequently popular for other purposes, including recitals and the Royal Tournament. The most glamorous event to take place was the Grand Ball held for the Belgian Volunteer regiments during their visit to England in July 1867. Other events at the “Aggie” included military tournaments, walking matches, missionary exhibitions, musical recitals, dairy shows, balls, mule and donkey shows, revivalist meetings, circuses, dog shows, motorcycle and cycle shows, trade fairs, and in 1870 a bullfight. In 1884 the prefix “Royal” was added because of the number of visits by Queen Victoria and members of the Royal Family.[22][5][6][6]

In 1943, after the nearby Mount Pleasant sorting office was bombed, the building was requisitioned for use during World War II and never re-opened to the public. It continued as a sorting office until 1971, then lay empty and deteriorating until eventually the main hall was redeveloped as the Business Design Centre in the 1980s. The remainder of the building was demolished and the main entrance moved from Liverpool Road to the Upper Street side.

The Royal Agricultural Hall features as the location for a Victorian walking match in Peter Lovesey’s 1970 novel Wobble to Death,[24] and its BBC Radio's Saturday Night Theatre adaptation.

Liverpool Road is unusual in being one of the few streets in London to have a "high pavement". This was constructed in the 1860s to protect pedestrians from being splashed by the large numbers of animals using the road to reach the then-new Agricultural Hall. As a consequence, the pavement is approximately 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) above the road surface for some lengths of the street.[25]

London Fever Hospital

Old Royal Free Place and Old Royal Free Square were originally the London Fever Hospital, and then from 1948 an annexe to the Royal Free Hospital. The London Fever Hospital moved to Kettle Field on Liverpool Road in 1848 from its earlier premises at King's Cross when the site was needed as part of the site for the Great Northern Railway terminus at King's Cross Station. Despite much local opposition, Liverpool Road was believed to be a much better position for a fever hospital because it was on the top of a gravel ridge, high and well drained, and thought likely to be free of the miasma, or bad air, held to cause disease.[26]

The architect for the new hospital was Charles Fowler, who received the commission due to the influence of the Earl of Devon. The circumstances caused some controversy: a competition had been held to choose a design, and one by David Mocatta had been formally decided upon by the committee, but it was set aside and Fowler was brought in to carry out the work.[27] Fowler designed the red-brick, colonnaded façade in Palladian style, with two wings. The front façade consisted of the front elevation with three blocks linked by single-storey colonnades very much as seen today. The central block and colonnades were intended to house offices, stores and the committee room. The Victorians used this design to disguise the wards of typhoid and scarlet fever patients, who were admitted from 1849. Behind were two flanking blocks which were occupied by 'superior class wards', incorporating the latest ideas of the time for healthy nursing.

In 1862 Charles Dickens described the hospital as “not only the single hospital of its kind in London but probably the best hospital of its kind in Europe”.

The hospital suffered bomb damage during World War II, became part of the Royal Free in 1948, and eventually closed in 1975. From 1990 the surviving buildings were converted to residential use.[28][29][30]

Holy Trinity Church

Islington is known for its large (about 30) number of garden squares, and Liverpool Road’s route is near to several, including Cloudesley, Gibson, Milner, Lonsdale, Barnsbury, and Arundel Squares. The squares mostly date to the early 19th century when they were included in building plans as an attractive and fashionable amenity to justify charging higher rents from wealthier occupants of the surrounding houses. Cloudesley Square is accessed between nos. 141 and 143 Liverpool Road, from where Holy Trinity Church is visible.

Cloudesley Square was the earliest Barnsbury square to be built, in 1826-9. The centre is occupied by Holy Trinity Church, which was designed by the young Charles Barry in the newly fashionable Perpendicular style and recognisably copying King’s College Chapel, Cambridge.[31] A handsome painted window commemorates Richard Cloudesley who died in 1517 and bequeathed to the parish the piece of ground called the “Stony Field” (hence nearby Stonefield Street) upon which the church is built, asking that thirty requiem masses a year should be said for the repose of his soul forever. He bequeathed in his will an allowance of straw for the prisoners of Newgate, King's Bench, Marshalsea prisons and the mad inmates of Bedlam, gowns valued at 6s 8d each for the poor and a number of bequests. These are still administered by the Cloudesley charity.[32][6][33]

The church was declared redundant in the 1960s and remained empty until 1980 when it was leased by a Nigerian Pentecostal community, the Celestial Church of Christ. Possession was returned to the Diocese of London in 2018.

Islington workhouse

Islington workhouse was formerly located off Liverpool Road. A workhouse had been operating at nearby locations since 1729, until the first purpose-built building was constructed in 1777 in spacious grounds off “Cut Throat Lane”, now the west range of Barnsbury Street, at the junction with Liverpool Road. It ceased to be a workhouse in 1872 and the buildings were demolished and a new block erected at the south-east of the site as the district relieving offices, labour bureau and smallpox vaccination centre. No. 281 Liverpool Road, the curious asymmetrical turreted building of 1872 at the corner, was used until 1969 as the Registrar’s Office for Births, Deaths and Marriages.[34][35][11][6][36] All the surviving buildings have now been converted to residential use.

College Cross

Between nos. 220 and 222 Liverpool Road, a short road leads into College Cross. Here the Church Missionary College stood from 1825 to 1915 on the site of the present Sutton Dwellings. The college was built by the Church Missionary Society on the site of a large 18th century botanic garden.[37][38]

Thomas Cubitt houses

Nos. 230-254 Liverpool Road, part of the former Manchester Terrace (c.1827) and backing on to College Cross, is one of the few developments in this area known to be by Thomas Cubitt, with segmental arched windows.[39]

Samuel Lewis Trust Dwellings and Laycock Green

The Samuel Lewis Trust Dwellings and adjacent Laycock Green (formerly the site of the Liverpool Buildings) are on the former Laycock Farm.

“Laycock’s Farm & Cattle Lairs” started as early as 1720. Charles Laycock, Jnr. who died in 1777 was “one of the greatest goose-feeders and wholesale poulterers in the kingdom.” Richard Laycock, who died in 1834 was the proprietor of one of the largest dairies in the country and one of the richest dairy-farmers of his day. Over 500 acres were farmed around Liverpool Road and Upper Street, stretching south as far as what is now Islington Park Street.[40][6] Cattle being driven to Smithfield would often feed and rest overnight in the cattle lairs which remained until the 1890s in the street named after him. His lairs were covered, and hence more profitable than many others along Liverpool Road.[41][42]

In 1882 the Improved Industrial Dwellings Co. Ltd. built four sets of model dwellings, Liverpool Buildings, on part of the farm site at the western end of Highbury Station Road.[43] These had been demolished by 1990, and the land was landscaped as a public park named Laycock Green.

Samuel Lewis was a wealthy financier and philanthropist, who left an endowment of £670,000 for the purpose of establishing a charity to provide housing for the poor. The Samuel Lewis Trust was set up in 1901 and the Samuel Lewis Trust Dwellings at Liverpool Road was the first of eight London housing projects. The estate of 323 dwellings opened on 4 April 1910 and was built by Wallis and Sons Ltd at a cost of £101,000. The buildings were designed by C S Joseph and Smithem and consist of five rows of blocks with trees between them, including notable pollarded planes, and small island gardens set in paved areas. Nikolaus Pevsner described the estate as “the best illustration in Islington of the tremendous improvement in standards of planning and humane appearance that became apparent in the best working class housing around 1900”.[44] The units each had a coal bunker, and there was a bath underneath a wooden top in the kitchens.

In 2001, the Trust celebrated its centenary year and changed its name to Southern Housing Group.

St Mary Magdalene Church and Gardens

St Mary Magdalene Church is situated in gardens between Liverpool Road and Holloway Road. It was built in 1814 to a design by William Wickings as a chapel of ease to the parish church of St. Mary's farther south on Upper Street. The site chosen had space for both the church and a churchyard and burial ground. However, its final cost, £32,636, was so high that a committee of investigation was appointed, which found that much of it was wasted thanks to an absence of a specific contract. Its design drew little praise.[45] It became a parish church in its own right in 1894, and is now part of the parish of Hope Church Islington.

The actress Jane Russell attended a couple of services at the church in November 1954, while she was filming Gentlemen Marry Brunettes.[46]

The church gardens are the church's old burial ground. As the land approached the end of its useful life as a burial plot at the end of the 19th century, an Act of Parliament was passed to allow the transition from remembrance gardens into a public park. Many of the tombs and headstones were removed, the land enlarged and formal rose gardens added.[47]

St Mary Magdalene Academy

A welcome benefit of the building of St Mary Magdalene Church was a new parochial school, built at the rear alongside what became Liverpool Road, opening in 1815 on half an acre of land and catering for 400 children. It ran on the Madras System (hence the nearby Madras Place), reducing costs by using the abler pupils as “helpers” to the teacher, passing on the information they had learned to other students.[48] On 7th/8th October 1940, a bomb destroyed the school and the surrounding area. A new building was opened in 1954, as a voluntary aided Church of England primary school, junior mixed and infants.[11][6] The building was recently rebuilt, and the school became St Mary Magdalene Academy, with a primary school and a secondary school including sixth form.

Transport

Liverpool Road crosses the railway lines which form part of London Underground's Victoria line and Great Northern's Northern City Line, as well as London Overground's East and North London Lines. The bridge over the railway lines marks the change from the N1 to the N7 postcode.

The first tramway in Islington was opened in 1871 by the North Metropolitan Tramways Co. from the Nag's Head, Holloway Road, to the Angel via both Upper Street and Liverpool Road, and on to Finsbury Square. It was extended to Archway Tavern and Finsbury Park in 1872.[50] Liverpool Road proved to be “probably the least revenue-providing thoroughfare of any length in London through which trams operated”, and the service was halted in 1913.[51] There has been no tram or bus service along the road since.

In 2003, traffic calming measures were introduced along the road to reduce the volume and speed of traffic. After changes in 2019 to the layout of Highbury Corner, there was a substantial increase in vehicles rat running along Liverpool Road and other nearby roads to avoid the disruption caused by the new layout, resulting in significantly increased noise and pollution. Residents are lobbying Islington Council for mitigation measures.

See also

- List of people from Islington

- Islington Museum

- Islington Local History Centre

- Business Design Centre

- Upper Street

- Islington High Street

- Barnsbury

- Angel, London

- The Angel, Islington

- Holloway Road

References

- 'Islington: Communications', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 8: Islington and Stoke Newington parishes (1985), pp. 3–8. Retrieved 9 March 2007

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. p. 120. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). The Buildings of England: London 4: North (1 ed.). Yale University Press / English Heritage. p. 699. ISBN 978-0300096538.

- Cosh, Mary (1981). An historical walk through Barnsbury. London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0 9507532 0 3.

- Willats, Eric A. (1987). Streets with a Story: Islington (PDF). p. 140. ISBN 0 9511871 04.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. Great Britain: Sidgwick & Jackson. pp. 122, 124. ISBN 0 283 97937 2.

- Cosh, Mary (1981). An historical walk through Barnsbury. London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0 9507532 0 3.

- Jacobs, Keith. "Brooksby Street, Islington N1". LARP Islington.

- Reading, Michael (2011). "Letters" (PDF). Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society. 1 (1 Spring 2011): 6.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. Great Britain: Sidgwick & Jackson. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0 283 97937 2.

- Willats, Eric A. (1987). Streets with a Story: Islington (PDF). p. 142. ISBN 0 9511871 04.

- Ackroyd, Peter (2002). Dickens. Great Britain: Vintage. p. 104. ISBN 0 09 943709 0.

- Schlicke, Paul (1999). Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 536. ISBN 0 19 866253 X.

- Patten, Robert L. (1972). Introduction to The Pickwick Papers. London: Penguin. p. 15. ISBN 0 14 04 3078 4.

- </ "Toyah Willcox and Islington Council commemorate Derek Jarman at his old flat in Liverpool Road".

- "Heritage Plaques". Islington Life. London Borough of Islington. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Peter Paillou". London Metropolitan Archives. City of London.

- "Peter Paillou". City of London: London Metropolitan Archives. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Pub wiki". Pub wiki London.

- "London Pubology". London Pubology London.

- "History". The Royal Smithfield Club. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. pp. 278–281. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Lovesey, Peter (1970). Wobble to Death. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0 333 11069 2.

- Corby, Chris (March 2004). "Angel Town Centre Strategy" (PDF). London Borough of Islington. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- "Islington: Public services". British History Online.

- "Buildings for Public Purposes". The British Almanac: 239. 1849.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. Great Britain: Sidgwick & Jackson. pp. 121–122. ISBN 0 283 97937 2.

- "The History and Redevelopment of the Royal Free Hospital Site in Islington". Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. p. 329. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Cosh, Mary (1993). The Squares of Islington Part II: Islington Parish. London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. pp. 44–49. ISBN 0 9507532 6 2.

- Willats, Eric A. (1987). Streets with a Story: Islington (PDF). p. 54. ISBN 0 9511871 04.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. Great Britain: Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 99. ISBN 0 283 97937 2.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. pp. 126–132. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Cosh, Mary (1981). An historical walk through Barnsbury. Islington Archaeology & History Society. p. 14. ISBN 0 9507532 0 3.

- Higginbotham, Peter. "The Workhouse in Islington (St Mary), London: Middlesex". The Workhouse: the story of an institution...

- Cosh, Mary (1981). An historical walk through Barnsbury. Islington Archaeology & History Society. p. 25. ISBN 0 9507532 0 3.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. pp. 169–170. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Cosh, Mary (1981). An historical walk through Barnsbury. Islington Archaeology & History Society. p. 24. ISBN 0 9507532 0 3.

- Willats, Eric A. (1987). Streets with a Story: Islington (PDF). p. 137. ISBN 0 9511871 04.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. Great Britain: Sidgwick & Jackson. pp. 20, 128. ISBN 0 283 97937 2.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. pp. 225–226. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Reading, Michael (2015). "The Highbury Pantechnicon" (PDF). Journal of the Islington Archaeology & History Society. 4 (4 Winter 2014-15): 12–13.

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). The Buildings of England: London 4: North (1 ed.). Yale University Press / English Heritage. ISBN 978-0300096538.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. p. 163. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Miles, Adrian; Goodman, Liz (May 2005). St Mary Magdalene - London Borough of Islington Archaeological Assessment. London: Museum of London Archaeology Service. p. 14.

- "St Mary Magdalene Gardens, Islington". St Mary Magdalene Gardens, Islington.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. pp. 163, 202, 208. ISBN 0 948667 97 4.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. Great Britain: Sidgwick & Jackson. p. 155. ISBN 0 283 97937 2.

- "Islington: Communications". British History Online.

- Wilson, Geoffrey (1971). London United Tramways : A History - 1894 to 933. London: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0043880010.