Letitia Woods Brown

Letitia Woods Brown (October 24, 1915 – August 3, 1976) was an African American researcher and historian. Earning a master's degree in 1935 from Ohio State University and a Ph.D. in 1966 from Harvard University, she served as a researcher and historian for over four decades and became one of the first black woman to earn a PhD from Harvard University in history. As a teacher, she started her career in Macon County, Alabama between 1935 and 1936. Later in 1937, she became Tuskegee Institute's instructor in history but left in 1940. Between 1940 and 1945 she worked at LeMoyne-Owen College in Memphis, Tennessee as a tutor. From 1968 to 1971, she served as a Fulbright lecturer at Monash University and Australia National University followed by a period in 1971 working as a consultant at the Federal Executive Institute. Between 1971 and 1976 she served as a history professor in the African-American faculty of George Washington University and became the first full-time black member. She also served as a primary consultant for the Schlesinger Library’s Black Women Oral History project during the course of her professional career. Aside from teaching history, Brown wrote and contributed to books on Washington DC such as Washington from Banneker to Douglas, 1791 – 1870 and Washington in the New Era, 1870 – 1970.

Dr. Letitia Woods Brown | |

|---|---|

Letitia Woods Brown | |

| Born | October 24, 1915 Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | August 3, 1976 (aged 60) Washington, DC, U.S. |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation | |

| Years active | 1935–1976 (as a teacher) |

| Spouse(s) | Theodore Edward Brown (1947–1976; her death) |

| Children | 2 |

Early life and education

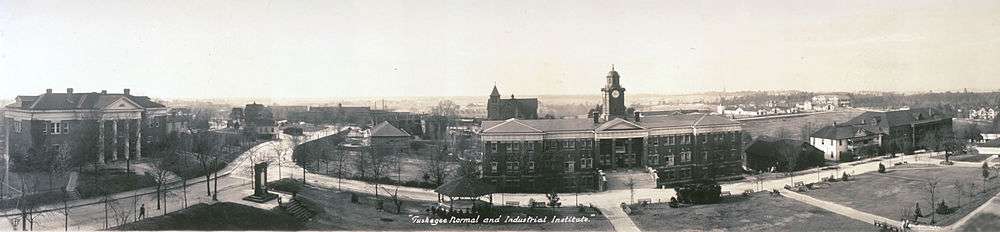

Letitia Woods Brown (née Letitia Christine Woods) was born on October 24, 1915, to Evadne Clark Adam Woods and Matthew Woods in Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S.[1][2] One of three daughters, Letitia was the second child.[3] The Woodses were a middle-class family; both parents worked as teachers at the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), an industrial college established by Booker T. Washington.[2][3][4] Matthew Woods was educated at the Tuskegee Institute. Letitia's mother Evadne Woods was one of twelve children born to Lewis Adams and Theodosia Evadne Clark. Her father Lewis Adams was a former slave who became a Tuskegee Normal School trustee and a commissioner in 1881. They all served as educators throughout the southern USA.[5]

Letitia Woods Brown attended Tuskegee Institute, as her father had.[3][4] She graduated with a bachelor of science degree in 1935, during the middle of the Great Depression.[1][2][3][6] While she continued her education, she briefly served as a teacher in the Macon County, Alabama segregated school system, where she taught 3rd and 4th grade in 1935 and 1936.[1][2][3] She once stated, "The rural black school in the segregated post-depression era was deprived by any standard. There were never enough books and the teacher had to provide her own chalk, paper, pencils...".[3] She subsequently obtained a Master of Arts degree in history from Ohio State University in 1937.[1][2] It was a time when women of African American ancestry were unlikely to continue higher education and pursue degrees. After graduating from Ohio State, Brown and a group of Ohio State University students traveled to Haiti to pursue academic knowledge about Caribbean history and literature. She later wrote, "That trip was my first sally forth to see the world".[3][6]

Career

On her return from Haiti, Brown moved to Alabama in 1937 and worked at the Tuskegee Institute as a history teacher until 1940.[1][2][3] In 1940, she joined LeMoyne-Owen College as a history teacher after a move from Alabama to Memphis, Tennessee.[1][3] She continued teaching at LeMoyne-Owen College until 1945.[1][2] Brown faced the same problem as most black educators during that era, in that they were offered appointments to teaching positions in higher education only in historically African American universities and colleges. She returned briefly in 1945 to Ohio State University to take additional classes in Eastern history and geography.[3][6]

To seek a PhD degree in history, Brown moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts to attend Harvard University[1][3] where she met Theodore Edward Brown. The couple married in 1947 and moved to her husband's hometown, Harlem.[3][6]

They moved again to Mount Vernon, New York where she worked at the local health and welfare council. Brown's efforts in the election campaign to elect an African-American proved successful and Harold Wood was elected to the Westchester County Board of Supervisors.[6] She wrote, "At one point the plan we projected for electing a black to the County Board of Supervisors sounded so convincing we decided we really ought to try it... Harold Wood won the election to become the first back to serve on the Westchester County Board of Supervisors".[3]

The family again relocated in 1956 to Washington, DC. There she served at the Bureau of Technical Assistance as an economist. While living in Washington, her interest in the African American history of the District of Columbia grew.[3] In later years, the topic became a major part of Brown's lectures and research. During her course for a doctorate at Harvard, Brown taught at the university, first as a teacher of social science and later of history, from 1961 to 1970.[3] She was later appointed an associate professor. In addition to teaching and researching for her doctorate dissertation, Brown and her husband trained the earliest group of volunteers for the Peace Corps in preparation for a 1961 deployment in Ghana.[6]

At the age of 51, in 1966 Brown completed her PhD history course 18 years after she started, to become one of the first African American woman to obtain a PhD from Harvard University in history.[1][2][3][7][8]

In 1968 Brown served as a Fulbright lecturer at Australian National University and Monash University in Australia.[1][2][9] Brown travelled to every part of southern Asia and southern Europe including Singapore, Jaipur, Istanbul, France and Italy before returning to America. On her return to the U.S. in 1971 she became a professor at George Washington University in the American Studies Department.[6] Brown was the only black faculty member to serve full-time.[10][11] She remained a member of George Washington University until her death in 1976.[1][2] In 1972, Brown travelled again, this time to African cities which include Gao, Cairo, Segou, Marrakesh, Timbuktu, Fez, Ibandan, Benin, Axum, Kumasi and Luxor.[3]

Brown joined the American Historical Association committee on her return and served there until 1973. Her efforts helped to establish the Columbia Historical Society of Washington DC in 1973.[6]

Mastering the use of oral history, she also served in the Schlesinger Library’s Black Women Oral History project at Radcliffe College as a primary consultant.[3][6][12][13]

Books

Apart from serving as a teacher and researcher, Brown wrote and contributed to several books on Washington, DC during her last years. Some of her books are:[1][2][3]

- Washington from Banneker to Douglass, 1791 – 1870 (1971) co-authored by Elsie M. Lewis.[14]

- Washington in the New Era, 1870 – 1970 (1972) co-authored by Richard Wade.[15]

- Free Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1790–1846[7][16]

- Residence Patterns of Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1800–1860[17]

- Free Negroes in the Original District of Columbia[18]

Personal life

Brown married Theodore Edward Brown in 1947 and settled briefly in his hometown, Harlem.[6] She met him while she was pursuing her doctorate in history from Harvard University. Theodore Brown was a doctoral student in Harvard University in the field of economics.[3] He later became an economist.[1][2][15]

They had two children: Lucy Evadne Brown was born in 1948 and Theodore Edward Brown Jr. followed in 1951.[3][6]

Death

After a career of more than four decades,[1][9] Brown died at home aged 60 on August 3, 1976 in Washington, DC after battling cancer.[1][2][3][6]

Professor of philosophy at George Washington University, Roderick S. French said at the memorial service held at National Cathedral's Bethlehem Chapel on August 7, 1976 that:[3][19]

Strong, intelligent, good-humored Letitia Woods Brown was instructor to all of us. I cannot imagine the person- man or woman- fortunate enough to be associated with her, who would have been so complacent or so dogmatic as never to have been surprised into new understanding by Letitia. Her creative intelligence was continuous, immediate, ultimate by specialization and individual.

Recognition

Following her death in 1976, the Association of Black Women Historical Society under Nell Irvin Painter's presidency established an award in her name, the Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Book Award in 1983 to honor scholars whose publications in the field of African-American Women's history are the best examples. An annual lecture in history at The Historical Society of Washington, DC was named "The Letitia Woods Brown Lecture". The Letitia Woods Brown Fellowship was also established by George Washington University in the field of African American history and culture.[6][20]

In November 2013, George Washington University organized the Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Lecture to celebrate the memory of Brown in the Jack Morton Auditorium.[7][21] The ceremony was free and open to the public.[7] Among others, Steven Knapp, current president of George Washington University was present at the lecture.[7][21] During the lecture Knapp described Brown as "the first full-time African American professor at George Washington, a scholar of the history of the District of Columbia and a tireless advocate for the preservation of the city's heritage".[21]

References

Citations

- "American Women Historians, 1700s – 1990s: Letitia Woods Brown", http://abwh.org/, Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH), retrieved January 12, 2015 External link in

|website=(help) - "Brown, Letitia Woods: Encyclopedia". http://encyclopedia.jrank.org/. J RANK Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - Jones, Ida E., "Letitia Woods Brown Memorial Book and Article Award: "Something for me, my family, the race and mankind: Letitia Woods Brown, 1915–1976"", abwh.org/, Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH), retrieved January 12, 2015

- Ware 2004, p. 83.

- Ware 2004, pp. 83–84.

- Ware 2004, p. 84.

- Lopez, Julyssa (November 13, 2013). "Lecture celebrate contributions DC History". George Washington Today. George Washington University. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "Bday Letitia Woods Brown pioneer in researching and teaching African American history completed PhD at Harvard". nwhp.org/. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- Lopez D. Matthews, Jr. "Letitia Woods Brown (1915–1976)". http://h-net.msu.edu/. msu.edu. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - Scanlon & Cosner 1996, p. 31.

- "Letitia Woods Brown, one of the first black historians in the country to gain international fame". utexas.edu/. U Texas. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "October Highlights in U.S. Women's History". rowan.edu/. Rowan Education. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "October in Women's history". http://womenstudies.unm.edu/. Women Studies. Retrieved January 13, 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - Lewis & Brown 1971, p. 2.

- Scanlon & Cosner 1996, p. 32.

- Brown 1972, pp. 1–2.

- Brown 1971, pp. 1–2.

- Brown 1966, pp. 1–2.

- French 1980, p. 522.

- "Monday open thread prominent black historians". https://pragmaticobotsunite.com/. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - Lopez, Julyssa (November 18, 2013). "Letitia Woods Brown lecture honors DC Historical studies". George Washington Today. George Washington University. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

Bibliography

- Ware, Susan (2004). Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century (5 ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674014886. Retrieved January 12, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scanlon, Jennifer; Cosner, Shaaron (October 21, 1996). American Women Historians, 1700s–1990s: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313296642. Retrieved January 12, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- French, Roderick S. (1980). Roderick S. French Records of Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. (50 ed.). Historical Society of Washington, D.C. doi:10.2307/40067835. JSTOR 40067835.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Letitia Woods (September 14, 1972). Free Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1790-1846. Oxford University Press. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

Letitia Woods Brown.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Brown, Letitia Woods (1971). Residence Patterns of Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1800–1860. Washington, D.C.: Columbia Historical Society. Retrieved January 13, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Letitia Woods (1966). Free Negroes in the Original District of Columbia. Harvard University. Retrieved January 13, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Elsie M.; Brown, Letitia Woods (1971). Washington from Banneker to Douglass, 1791–1870. Education Department, National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved January 13, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)